Al-Muqawqis

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2009) |

Al-Muqawqis |

|---|

Al-Muqawqis (Arabic: المقوقس, Coptic: ⲡⲭⲁⲩⲕⲓⲁⲛⲟⲥ, ⲡⲓⲕⲁⲩⲕⲟⲥ, romanized: p-khaukianos, pi-kaukos[1][2][3] "the Caucasian") is mentioned in Islamic history as a ruler of Egypt who corresponded with the Islamic prophet Muhammad. He is widely identified with the last prefect of Egypt Cyrus of Alexandria, who was the Greek (Melchite) patriarch of the second Byzantine period of Egypt (628-642). However, an alternative view identifies al-Muqawqis with the Sassanid governor of Egypt, said to be a Greek man named "Kirolos, leader of the Copts," although the Sassanian governor at the time was the military leader named Shahrbaraz.

Account by Muslim historians[]

Ibn Ishaq and other Muslim historians record that sometime between February 628 and 632, Muhammad sent epistles to the political heads of Medina's neighboring regions, both of Arabia and of the non-Arab lands of the Near East, including al-Muqawqis:

[Muhammad] had sent out some of his companions in different directions to the kings [recte sovereigns] of the Arabs and the non-Arabs inviting them to Islam in the period between al-Ḥudaybiya and his death...[he] divided his companions and sent...Ḥāṭib b. Abū Baltaʿa to the Muqauqis ruler of Alexandria. He handed over to him the...[5]

Tabari states that the delegation was sent in Dhul-Hijja 6 A.H. (April or May 628).[6] Ibn Saad states that the Muqawqis sent his gifts to Muhammad in 7 A.H. (after May 628).[7] This is consistent with his assertion that Mariya bore Muhammad's son Ibrahim in late March or April 630,[7] so Mariya had arrived in Medina before July 629.

Letter of invitation to Islam[]

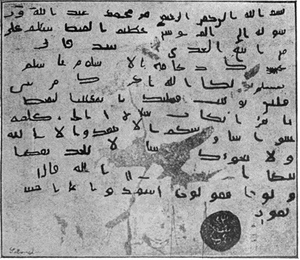

The epistle that Muhammad sent to al-Muqawqis, through his emissary Hatib ibn Abi Balta'ah, and his reply are both available. The letter reads as follows:[8]

From Muhammad, servant of God and His apostle to al-Muqawqis, premier of Egypt:

Peace unto whoever followeth the guided path!

And thereafter, I verily call thee to the call of Submission [to God] ("Islam"). Submit (i.e., embrace Islam) and be safe [from perdition, as] God shall compensate thy reward two-folds. But if thou turn away, then upon thee will be the guilt [of delusion] of the Egyptians.

Then "O People of the Scripture, come to a term equitable between us and you that we worship none but God and associate [as partners in worship] with Him nothing, and we take not one another as Lords apart from God. [Then God says] But if they turn away, then say: Bear witness that we are Submitters [to God] ("Muslims")."[Quran 3:64]

The epistle was signed with the seal of Muhammad.

Al-Muqawqis ordered that the letter be placed in an ivory casket,[7] to be kept safely in the government treasury. The letter was found in an old Christian monastery among Coptic books in the town of Akhmim, Egypt and now resides in the Topkapi Palace Museum (Department of Holy Relics) after the Turkish sultan Abdülmecid I brought it to Istanbul.[9] Al-Muqawqis is said to have replied with a letter that read:[10]

To Muhammad son of Abd-Allah from al-Muqawqis, premier of Egypt:

Peace unto thee!

Thereafter, I have already read thy letter, and comprehended what thou mentioned therein and what thou called me to. I have known that a prophet is still due [to come] but I thought he would emerge in the Levant (aš-Šām).

I have already treated with dignity thy messenger, and I am sending to thee two slave-girls whose position in Egypt is great, and [also] clothes, and I am sending as gifts to thee a she-mule for thee to ride. Then [I end here:] Peace unto thee!

The two slave-girls mentioned are Maria, whom Muhammad himself married, and her sister Shirin whom he married to Hassan ibn Thabit.[7]

It is said that a recluse in the monastery pasted it on his Bible and from there a French orientalist obtained it and sold it to the Sultan for £300.[citation needed] The Sultan had the letter fixed in a golden frame and had it preserved in the treasury of the royal palace, along with other sacred relics. Some Muslim scholars have affirmed that the scribe was Abu Bakr.[citation needed] Contemporary analytical historiography doubts the precise content of the letter (together with the similar letters sent to several power figures of the ancient Near East).[citation needed] Authenticity of the preserved samples and of the elaborate accounts by the medieval Islamic historians regarding the events surrounding the letter has also been questioned by modern historians.[11]

Dialog with Mughira ibn Shu'ba[]

According to another account, Al-Muqawqis also had a dialogue with Mughira ibn Shu'ba, before Mughira became a Muslim. Mughira said:[12]

Once I went to the court of al-Muqawqis, who inquired of me, about the family of the Prophet. I informed him that he belonged to a high and noble family. Al-Muqawqis remarked that prophets always belong to noble families. Then he asked if I had an experience of the truthfulness of the Prophet. I said that he always spoke the truth. Therefore, in spite of our opposition to him, we call him al-ʾamīn ("trustworthy"). Al-Muqawqis observed that a man who did not speak lies to men, how could he speak a lie about God? Then he inquired what sort of people his followers were and what the Jews thought of him. I replied that his followers were mostly poor, but the Jews were his bitter enemies. Al-Muqawqis stated that the followers of the prophets, in the beginning, are usually poor and that he must be a prophet of God. He further stated that the Jews opposed him out of envy and jealousy, otherwise, they must have been certain of his truthfulness, and that they too awaited a prophet. The Christ also preached that following and submitting to the prophet was essential and that whatever qualities of his had been mentioned, the same were the qualities of the earlier prophets.

Regarding al-Muqawqis' behavior in Islamic traditions, it is of note that when the general of the Arab conquest of Egypt 'Amr ibn al-'As (known to the East Romans as "Amru") threatened the Prefecture of Egypt, Cyrus of Alexandria as prefect was entrusted with the conduct of the war. Certain humiliating stipulations, to which he subscribed for the sake of peace, angered his imperial master so much that he was recalled and harshly accused of connivance with the Saracens. However, he was soon restored to his former authority owing to the impending siege of Alexandria, but could not avert the fall of the city in 640. He signed a peace treaty that surrendered Alexandria and Egypt on 8 November 641 before dying in 642.[13]

Explanation of the name[]

The word muqawqis is the Arabized form of Coptic ⲡⲓⲕⲁⲩⲕⲟⲥ pi-kaukos (alternatively ⲡⲭⲁⲩⲕⲓⲁⲛⲟⲥ p-khaukianos), meaning "the Caucasian," the common epithet among the non-Chalcedonian Copts of Egypt for the Melchite (Chalcedonian) patriarch Cyrus, who was seen as the corrupter and foreign usurper to the throne of the Coptic patriarch Benjamin I.[2][3] The word was subsequently used by Arab writers for some other patriarchs in Alexandria such as George I of Alexandria ("Jurayj ibn Mīnā" Georgios son of Menas Parkabios;[14] alternatively, "Jurayj ibn Mattá"),[15] Cyrus' predecessor. According to the opponents of the identification of al-Muqawqis as Cyrus and advocates of the view that he was rather the governor of Sassanid Egypt, the Arabic name referred to the inhabitants of a Persian empire that extended all the way to the Caucasus.[citation needed]

Opposition to identification with Cyrus of Alexandria[]

The widely held view of identifying al-Muqawqis with Cyrus has been challenged by some as being based on untenable assumptions. Considering historical facts, the opponents of the identification point out that Cyrus did not succeed to the See of Alexandria until 630 AD, after Heraclius had recaptured Egypt. After the Persian invasion, "The Coptic patriarch Andronicus remained in the country, experiencing and witnessing suffering as a result of the occupation (Evetts, 1904, p. 486 ll. 8-11). His successor in 626, Benjamin I, remained in office well beyond the end of the occupation; during his time the Sassanians moderated their policy to a certain extent."[16]

Adherents to this state that al-Muqawqis was not a Christian patriarch but the Persian governor during the last days of the Persian occupation of Egypt. There must have been an abundance of Alexandrine women left after the massacre. "Severus b. al-Moqaffa...also reported that in Alexandria every man between the ages of eighteen and fifty years had been brutally massacred (Evetts, 1904, pp. 485 l. 10-486 l. 3)."[16] So from among the captive women, it seems that al-Muqawqis took two Coptic sisters and sent them to Muhammad as gifts, realizing that the Byzantines were gaining ground and would soon re-take Alexandria. One possible reason that the Sasanian governor was kind towards Muhammad is that it is alleged that Christian Arabs assisted in Persian victory over the Byzantine Empire, and al-Muqawqis simply wanted to reward Muhammad whom he saw as one of the Arab kings. "According to a Nestorian Syriac chronicle attributed to Elias, bishop of Merv (?), Alexandria was taken by treachery. The traitor was a Christian Arab who came from the Sassanian-controlled northeastern coast of Arabia."[16]

References[]

- ^ Werner., Vycichl (1984) [1983]. Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue copte. Leuven: Peeters. ISBN 9782801701973. OCLC 11900253.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Coquin, René-Georges (1975). Livre de la consecration du sanctuaire de Benjamin (in French). Paris: Institut Francais D - Archeologie Orientale. pp. 110–112.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Alcock, Anthony (1983). The Life of Samuel of Kalamun by Isaac the Presbyter. Warminster [Wiltshire], England: Aris & Phillips.

- ^ "the original of the letter was discovered in 1858 by Monsieur Etienne Barthelemy, member of a French expedition, in a monastery in Egypt and is now carefully preserved in Constantinople. Several photographs of the letter have since been published. The first one was published in the well-known Egyptian newspaper Al-Hilal in November 1904" Muhammad Zafrulla Khan, Muhammad: Seal of the Prophets, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1980 (chapter 12). The drawing of the letter published in Al-Hilal was reproduced in David Samuel Margoliouth, Mohammed and the Rise of Islam, London (1905), p. 365, which is the source of this image.

- ^ Guillaume, Alfred (1967). The Life Of Muhammad: A Translation of Ishaq's Sirat Rasul Allah (13th ed.). Karachi: Oxford University Press. p. 653. ISBN 0-19-636033-1. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- ^ Tabari, Tarikh al-Rusul wa'l-Muluk, vol. 8. Translated by Fishbein, M. (1997). The Victory of Islam, p. 98. New York: State University of New York Press.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Salloomi, M. Abd Allah Al (1996). Kitab at-Tabaqat al-Kubra of Muhammad Bin Sa'd (d.230/844): The Missing and Unpublished Part of the Third Generation (Tabaqah) of the Sahabah : a Critical Study and Edition. Lampeter: University of Wales. p. 260.

- ^ al-Jawzīyah, Muḥammad ibn Abī Bakr Ibn Qayyim (1973). Zad al-Ma'ad Fi Huda Khayr al-'Ibad (in Arabic). Beirut: Dar al-Fikr. p. 72.

- ^ Öz, Tahsin (1953). Hirka-i saadet dairesi ve Emanat-i mukaddese (in Turkish). İsmail Akgün Matbaasi. p. 47.

- ^ "حاطب بن أبي بلتعة سفيراً إلى المقوقس - الرياضي - البيان". albayan.ae (in Arabic). AlBayan. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ Bolshakov, Oleg Georgievich (1989). История Халифата (History of the Caliphate) (in Russian). "Наука, " Глав. ред. восточной лит-ры. ISBN 978-5-02-016552-6.

- ^ Hassan Shabazz, Hassan (2020). Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) the Savior of the World. ISBN 9781794880320.

- ^ Bierbrier, Morris L. (2008). Historical Dictionary of Ancient Egypt. Scarecrow Press. p. 56. ISBN 9780810862500. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- ^ Ibn Jirjis, Abū al-Mukārim Saʿd Allāh (1895). The Churches & Monasteries of Egypt and some neighbouring countries attributed to Abû Ṣâlih, the Armenian. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-813156-4.

- ^ Mubârakpûrî, Safî-ur-Rahmân (2002). Sealed Nectar : Biography of the Noble Prophet. Medina, Saudi Arabia: Dar-Us-Salam Publications. ISBN 978-1-59144-071-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Egypt iv. Relations in the Sasanian Period - Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- 7th-century Islam

- Muslim conquest of Egypt

- 7th-century Egyptian people

- Egyptian people of Greek descent