Alicia Keys

Alicia Keys | |

|---|---|

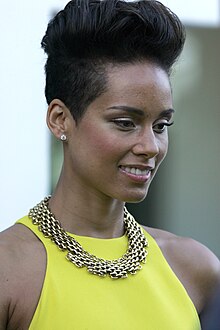

Keys in 2013 | |

| Born | Alicia Augello Cook January 25, 1981 New York City, U.S. |

| Other names | Lellow |

| Education | Professional Performing Arts School Columbia University |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1996–present |

| Organization | Keep a Child Alive |

| Spouse(s) | Swizz Beatz (m. 2010) |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards | Full list |

| Musical career | |

| Genres |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Labels |

|

| Associated acts |

|

| Signature | |

| |

Alicia Augello Cook (born January 25, 1981), known professionally as Alicia Keys, is an American singer-songwriter. A classically-trained pianist, Keys began composing songs by age 12 and was signed at 15 years old by Columbia Records. After disputes with the label, she signed with Arista Records and later released her debut album, Songs in A Minor, with J Records in 2001. The album was critically and commercially successful, producing her first Billboard Hot 100 number-one single "Fallin'" and selling over 12 million copies worldwide. The album earned Keys five Grammy Awards in 2002.

Her second album, The Diary of Alicia Keys (2003), was also a critical and commercial success, spawning successful singles "You Don't Know My Name", "If I Ain't Got You", and "Diary", and selling eight million copies worldwide.[1] The album garnered her an additional four Grammy Awards.[2] Her duet "My Boo" with Usher became her second number-one single in 2004. Keys released her first live album, Unplugged (2005), and became the first woman to have an MTV Unplugged album debut at number one. Her third album, As I Am (2007), produced the Hot 100 number-one single "No One", selling 7 million copies worldwide and earning an additional three Grammy Awards. In 2007, Keys made her film debut in the action-thriller film Smokin' Aces. She, along with Jack White, recorded "Another Way to Die" (the title song to the 22nd official James Bond film, Quantum of Solace). Her fourth album, The Element of Freedom (2009), became her first chart-topping album in the UK, and sold 4 million copies worldwide. In 2009, Keys also collaborated with Jay Z on "Empire State of Mind", which became her fourth number-one single and won the Grammy Award for Best Rap/Sung Collaboration. Girl on Fire (2012) was her fifth Billboard 200 topping album, spawning the successful title track, and won the Grammy Award for Best R&B Album. In 2013, VH1 Storytellers was released as her second live album. Her sixth studio album, Here (2016), became her seventh US R&B/Hip-Hop chart-topping album. Her seventh studio album, Alicia, was released on September 18, 2020.[3]

Keys has received numerous accolades in her career, including 15 competitive Grammy Awards, 17 NAACP Image Awards, 12 ASCAP Awards, and an award from the Songwriters Hall of Fame and National Music Publishers Association. She has sold over 90 million records worldwide making her one of the world's best-selling music artists and was named by Billboard the top R&B artist of the 2000s decade.[4] She placed tenth on their list of Top 50 R&B/Hip-Hop Artists of the Past 25 Years. VH1 included her on their 100 Greatest Artists of All Time and 100 Greatest Women in Music lists, while Time has named her in their 100 list of most influential people in 2005 and 2017. Keys is also acclaimed for her humanitarian work, philanthropy and activism, e.g. being awarded Ambassador of Conscience by Amnesty International; she co-founded and serves as the Global Ambassador of the nonprofit HIV/AIDS-fighting organization Keep a Child Alive.

Early life[]

Alicia Augello was born on January 25, 1981, in the Hell's Kitchen neighborhood of New York City.[5][6] She is the only child of Teresa Augello, who was a paralegal and part-time actress, and one of three children of Craig Cook, who was a flight attendant.[7][8][9] Keys's father is African American and her mother is of Italian, Irish, and Scottish descent; her mother's paternal grandparents were immigrants from Sciacca in Sicily.[10][11] Named after her Puerto Rican godmother,[12] Keys has said that she was comfortable with her multiracial heritage because she felt she was able to "relate to different cultures".[5][13] Keys's father left when she was two and she was subsequently raised by her mother during her formative years in Hell's Kitchen.[14] Keys said her parents never had a relationship, and her father was not in her life.[15] Although she did not like to speak about her father in order to not feed stereotypes, Keys remarked in 2001: "I'm not in contact with him. That's fine. When I was younger, I minded about that. [It] made me angry. But it helped show me what a strong woman my mother was, and made me want to be strong like her. Probably, it was better for me this way."[5] Keys and her mother lived in a one-room apartment.[14] Her mother often worked three jobs to provide for Keys, who "learned how to survive" from her mother's example of tenacity and self-reliance.[14][16]

"I grew up in the middle of everything. I walked the streets alone, I rode the trains alone, I came home at three in the morning alone, that was what I did ... The city had a huge influence on me because it's such a diverse place. As hard as [growing up in it was], I always felt very blessed about being able to recognize different cultures and styles, people and places. I feel like the concrete alone just gave me a certain drive. I really saw everything: every negative I could possibly see from the time I could walk until now; and also every positive, every bright future, every dream that I could possibly see. So growing up around this big dichotomy definitely influenced my music."

From a young age, Keys struggled with self-esteem issues, "hiding" little by little when her differences made her vulnerable to judgment, and later uninvited sexual attention.[18][19][20] Living in the rough neighborhood of Hell's Kitchen,[14][15] she was, from an early age, regularly exposed to street violence, drugs, prostitution, and subjected to sexual propositions in the sex trade- and crime-riddled area.[20][21][22] "I saw a variety of people growing up, and lifestyles, lows and highs. I think it makes you realise right away what you want and what you don't want", Keys said.[23] Keys recalled feeling fearful early on of the "animal instinct" she witnessed, and eventually feeling "high" due to recurrent harassment.[18][24] Her experiences in the streets had led her to carry a homemade knife for protection.[25][26] She became very wary,[26][27] emotionally guarded, and she began wearing gender-neutral clothing and what would become her trademark cornrows.[30] Keys explained that she is grateful for growing up where she did as it prepared her for the parallels in the music industry, particularly as she was a teenager starting out; she could maintain a particular focus and not derail herself.[20][31] She credits her "tough" mother for anchoring her on a right path as opposed to many people she knew who ended up on the wrong path and in jail. Keys attributed her unusual maturity as a young girl to her mother, who depended on her to be responsible while she worked to provide for them and give Keys as many opportunities as possible.[26][27]

Keys loved music and singing from early childhood. She recalled her mother playing jazz records of artists like Thelonious Monk, Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong on Sunday mornings, early musical moments Keys considers influential in kindling her interest in and emotional connection to music.[5][16] In preschool, Keys sang in her school's production of the musical Cats and was cast as Dorothy Gale in a production of The Wizard of Oz.[32] Keys discovered she had a passion for the piano by age six, as she loved the sound and feel of the instrument and desired to play and learn it.[17][33] When Keys was ten,[34] a neighborhood friend who was moving home gifted her family an old upright piano. This proved pivotal for Key's musical development, allowing her to practice, to play and fully benefit from music lessons at an early age.[15] Keys began receiving classical piano training by age seven,[35] practicing six hours a day,[33] learning the Suzuki method and playing composers such as Beethoven, Mozart, Chopin, and Satie.[15][36] She was particularly drawn to "blue, dark, shadowy" and melancholic compositions, as well as the passionate romanticism of "blue composers" like Chopin.[37] Inspired by the film Philadelphia, Keys wrote her first song about her departed grandfather on her piano by age 12. The scene in the film where Tom Hanks's character listens to opera on a record player notably affected Keys, who "never showed emotion very well".[17] After seeing the film, Keys, "for the first time, could express how [she] felt through the music."[15][33]

Classical piano totally helped me to be a better songwriter and a better musician ... I knew the fundamentals of music. And I understood how to put things together and pull it together and change it. The dedication that it took to study classical music is a big reason why I have anything in this life I think. ... [It] was a big influence on me. It opened a lot of doors because it separated me from the rest. [...] And it did help me structure my songs.

—Keys[17]

Keys's mother had encouraged her to participate in different extracurricular activities, including music, dance, theater, and gymnastics, so she could "find her muse".[32][38] Her extracurricular activities gave her focus and drive, and helped keep her out of trouble.[25][33][36] Keys remained so occupied with her various pursuits that she experienced her first burnout before adolescence. Before her 13th birthday, she expressed to her mother that she was too overwhelmed and wanted to disengage, at which point her mother took some time off with her and encouraged her to keep focusing on piano.[32] Keys would continue studying classical music until the age of 18.[33] Keys regards her education in classical piano and dedication to classical music as vital for her stability in her youth and her development as a musician and songwriter.[5][17] Keys later said of her classical background:

That type of studying, that type of discipline ... after a while, I realized what it provided me – focus, the ability to pay attention for a long enough period of time to make progress; the work ethic; the actual knowledge of music, that then unlocked the ability to write my own music, put my own chords and things I heard in my own head to different lyrics that I maybe felt, and I never, ever had to wait for anybody to write something for me.[39]

Keys enrolled in the Professional Performing Arts School at the age of 12, where she took music, dance, and theater classes and majored in choir.[7][20] In her preteen years, Keys and her bass-playing friend formed their first group, though neither "knew too much about how pop songs worked".[15][36] Keys would continue singing, writing songs, and performing in musical groups throughout junior high and high school.[16][32][35] She became an accomplished pianist, and after her classical music teacher had nothing left to teach her, she began studying jazz at age 14.[38][40] Living in the "musical melting pot" city, Keys had already been discovering other genres of music, including soul music, hip hop, R&B, and taken affinity to artists like Marvin Gaye and Curtis Mayfield. Keen on dissecting music, Keys continued developing her songwriting and finding her own 'flow and style" through her exploration of the intricacies in different music.[17][36][41]

Keys spent more time in Harlem during her teenage years. She connected with the cultural and racial diversity in the neighborhood, where she expanded upon her musical exploration, and her character was also solidified. "Harlem raised me in a lot of ways," Keys remarked. "[It] taught me how to think fast, how to play the game ... taught me leadership, how to get out of bad situations when you need to, how to hold my own."[5][35] During this period, she met her good friend who would later become her long-term collaborator and boyfriend Kerry Brothers Jr., also famously known as "Krucial".[16][35]

Career[]

1994–1997: Career beginnings[]

In 1994, manager Jeff Robinson met 13-year old Keys, who participated in his brother's youth organization called Teens in Motion.[32][42] Robinson's brother had been giving Keys vocal lessons in Harlem.[33] His brother had talked to him about Keys and advised him to go see her, but Robinson shrugged it off as he had "heard that story 1,000 times". At the time, Keys was part of a three-girl band that had formed in the Bronx and was performing in Harlem.[32][40] Robinson eventually agreed to his brother's request, and went to see Keys perform with her group at the Police Athletic League center in Harlem. He was soon taken by Keys, her soulful singing, playing contemporary and classical music and performing her own songs.[32][35] Robinson was excited by audiences' reactions to her. Impressed by her talents, charisma, image, and maturity, Robinson considered her to be the "total package", and took her under his wing.[38][40][42] By this time, Keys had already written two of the songs that she would later include on her debut album, "Butterflyz" and "The Life".[38][40]

Robinson wanted Keys to be informed and prepared for the music industry, so he took her everywhere with him, including all the meetings with attorneys and negotiations with record labels, while the teenager often became disgruntled with the process.[32] Robinson had urged Keys to pursue a solo career, as she remained reluctant, preferring the musical interactions of a group. She took Robinson's advice after her group disbanded, and contacted Robinson who in 1995 introduced her to A&R executive Peter Edge. Edge later described his first impressions of Keys to HitQuarters:

I remember that I felt, upon meeting her, that she was completely unique. I had never met a young R&B artist with that level of musicianship. So many people were just singing on top of loops and tracks, but she had the ability, not only to be part of hip hop, but also to go way beyond that. She's a very accomplished musician, songwriter and vocalist and a rare and unique talent.[43]

Robinson and Edge helped Keys assemble some demos of songs she had written and set up a showcases for label executives.[16][32][35] Keys performed on the piano for executives of various labels, and a bidding war ensued.[15][35] Edge was keen to sign Keys himself but was unable to do so at that time due to being on the verge of leaving his present record company, Warner Bros. Records, to work at Clive Davis' Arista Records.[15][32][43] During this period, Columbia Records had approached Keys for a record deal, offering her a $26,000 white baby grand piano; after negotiations with her and her manager, she signed to the label, at age 15. Keys was also finishing high school, and her academic success had provided her opportunity for scholarship and early admission to university.[15][32][43] That year, Keys accepted a scholarship to study at Columbia University in Manhattan.[16] She graduated from high school early as valedictorian, at the age of 16, and began attending Columbia University at that age while working on her music.[15][38] Keys attempted to manage a difficult schedule between university and working in the studio into the morning, compounding stress and a distant relationship with her mother. She often stayed away from home, and wrote some of the most "depressing" poems of her life during this period. Keys decided to drop out of college after a month to pursue music full-time.[16][29][38]

Columbia Records had recruited a team of songwriters, producers and stylists to work on Keys and her music. They wanted Keys to submit to their creative and image decisions.[16] Keys said they were not receptive to her contributions and being a musician and music creator.[38][39] While Keys worked on her songs, Columbia executives attempted to change her material; they wanted her to sing and have others create the music, forcing big-name producers on her who demanded she also write with people with whom she was not comfortable.[5][33] She would go into sessions already prepared with music she had composed, but the label would dismiss her work in favor of their vision.[39] "It was a constant battle, it was a lot of -isms", Keys recalled. "There was the sexism, but it was more the ageism – you're too young, how could you possibly know what you want to do? – and oh God, that just irked me to death, I hated that."[16] "The music coming out was very disappointing", she recalled. "You have this desire to have something good, and you have thoughts and ideas, but when you finish the music it's shit, and it keeps on going like that."[35] Keys would be in "perpetual music industry purgatory" under Columbia, while they ultimately "relegated [her] to the shelf".[40] She had performed "Little Drummer Girl" for So So Def's Christmas compilation in 1996,[40] and later co-wrote the song "Dah Dee Dah (Sexy Thing)" for the Men in Black (1997) film soundtrack, the only released recording Keys made with Columbia.[29][33]

Keys "hated" the experience of writing with the people Columbia brought in. "I remember driving to the studio one day with dread in my chest", she recalled.[15] Keys said the producers would also sexually proposition her.[5][20][38] "It's all over the place. And it's crazy. And it's very difficult to understand and handle", she said.[38] Keys had already built a "protect yourself" mentality from growing up in Hell's Kitchen, which served her as a young teen then in the industry having to rebuff the advances of producers and being around people who "just wanted to use [her]".[20][31] Keys felt like she could not show weakness.[20] Executives at Columbia also wanted to manufacture her image, with her "hair blown out and flowing", short dresses, and asking her to lose weight; "they wanted me to be the same as everyone else", Keys felt.[15] "I had horrible experiences," she recalled. "They were so disrespectful ... I started figuring, 'Hey, nothing's worth all this.'"[5] As months passed, Keys had grown more frustrated and depressed with the situation, while the label requested the finished tracks.[15][35][38] Keys recalled, "it was around that time that I realized that I couldn't do it with other people. I had to do it more with myself, with the people that I felt comfortable with or by myself with my piano."[38] Keys decided to sit in with some producers and engineers to ask questions and watch them technically work on other artists' music.[35] "The only way it would sound like anything I would be remotely proud of is if I did it", Keys determined. "I already knew my way around the keyboard, so that was an advantage. And the rest was watching people work on other artists and watching how they layer things".[35]

Her partner Kerry "Krucial" Brothers suggested to Keys she buy her own equipment and record on her own.[38] Keys began working separately from the label, exploring more production and engineering on her own with her own equipment.[35] She had moved out of her mother's apartment and into a sixth-floor walk-up apartment in Harlem with Brothers, where she fit a recording studio into their bedroom and worked on her music.[38] Keys felt being on her own was "necessary" for her sanity. She was "going through a lot" with herself and with her mother, and she "needed the space"; "I needed to have my own thoughts, to do my own thing."[35] Keys and Brothers later moved to Queens and together they turned the basement into KrucialKeys Studios.[38] Keys would return to her mother's house periodically, particularly when she felt "lost or unbalanced or alone". "She would probably be working and I would sit at the piano", she reminisced.[38] During this time, she composed the song "Troubles", which started as "a conversation with God", working on it further in Harlem. Around this time the album "started coming together", and she composed and recorded most of the songs that would appear on her album.[27][35][38] "Finally, I knew how to structure my feelings into something that made sense, something that can translate to people", Keys recalled. "That was a changing point. My confidence was up, way up."[35] The different experience reinvigorated Keys and her music.[38] While the album was nearly completed, Columbia's management changed and more creative differences emerged with the new executives. Keys brought her songs to the executives, who rejected her work, saying it "sounded like one long demo". They wanted Keys to sing over loops,[35] and told Keys they will bring in a "top" team and get her "a more radio-friendly sound". Keys would not allow it; "they already had set the monster loose", she recalled. "Once I started producing my own stuff there wasn't any going back."[38] Keys stated that Columbia had the "wrong vision" for her. "They didn't want me to be an individual, didn't really care", Keys concluded. "They just wanted to put me in a box."[5] Control over her creative process was "everything" to Keys.[39]

Keys had wanted to leave Columbia since they began "completely disrespecting [her] musical creativity".[15] Leaving Columbia was "a hell of a fight", she recalled. "Out of spite, they were threatening to keep everything I'd created even though they hated it. I thought I'd have to start over again just to get out, but I didn't care."[15] Keys said in 2001: "It's been one trial, one test of confidence and faith after the next." To Keys, "success doesn't just mean that I'm the singer, and you give me my 14 points, and that's all. That's not how it's going to go down."[44] Edge, who was by that time head of A&R at Arista Records,[16] said, "I didn't see that there was much hands-on development at Columbia, and she was smart enough to figure that out and to ask to be released from her contract, which was a bold move for a new artist."[38] Edge introduced Keys to Arista's then-president, Clive Davis, in 1998.[16][45] Davis recalled:

My only familiarity with [Keys] was that I had asked for any visuals and material on her, so, of course, I was blown away. I saw a panel show she had done on TV. I had heard some cuts she had been recording, and I honestly couldn't believe she could be free. She was still under contract. I left that to her. It took a few months before I got the call that she was able to get out of her contract and enter into one with us."[32]

After hearing some of her songs, Davis thought Keys had "a very natural talent as a songwriter and a vocalist, sufficient to warrant a personal meeting ... one of those no-brainers – her beauty is stunning, and all her talent as an arranger, a producer".[16] Regarding her first meeting with Davis, Keys said that she had "never had anyone of his stature ask me how I saw myself, and what I wanted to do."[15] Davis had asked Keys "what the creative visions were that she had for herself."[32]

She came across then, from that very first meeting, the way she comes across today, which is really as a young Renaissance woman of enormous musical talent, but really matured way beyond her young years. When I saw her sit down and play the piano and sing, it just took my breath ... Everything about her was unique and special.[32]

1998–2002: Breakthrough with Songs in A Minor[]

Robinson and Keys, with Davis's help, were able to negotiate out of the Columbia contract and she signed to Arista Records in late 1998.[33][38][43] Keys was also able to leave with the music she had created.[15] Davis gave Keys the creative freedom and control she wanted, and encouraged her to be herself.[5][45] Keys said of Davis' instinct: "he knows which artists are the ones that maybe are needing to craft their own sound and style and songs, and you just have to let an artist go and find that space. And I think he somehow knew that and saw that in me and really just let me find that."[40] After signing with Davis, Keys continued honing her songs.[5] Keys almost chose Wilde as her stage name at the age of 16 until her manager suggested the name Keys after a dream he had. She felt that name embodied her both as a performer and person.[46] Keys contributed her songs "Rock wit U" and "Rear View Mirror" to the soundtracks of the films Shaft (2000) and Dr. Dolittle 2 (2001), respectively.[47][48]

In 2000, Davis was ousted from Arista and the release of Keys's album was put on hold. Later that year, Davis formed J Records and immediately signed Keys to the label.[15] "He didn't try to divert me to something else", Keys said on following Davis to his new label. He understood that she wants to be herself and not "made into what somebody else thinks I should be."[29]

Keys played small shows across America, performed at industry showcases for months and then on television.[35][45] Davis thought "pop stations might feel she's too urban. Urban might feel she's too traditional", and as he felt Keys was a "compelling, hypnotic performer" best experienced in person, he had Keys perform her music to different crowds in different places to spread the word.[32][35][45] "I created opportunities for those who saw her to spread the word", Davis recalled. "She is her own ambassador."[32] Davis wanted to "let people discover her, and you can only do that with a few artists."[16][41] Keys later performed on The Tonight Show in promotion for her upcoming debut.[35] Davis wrote a letter to Oprah asking her to have Keys, Jill Scott, and India.Arie perform on her show to promote new women in music.[35] Oprah booked Keys the day she heard her song "Fallin'", her debut single.[5][32] Keys performed the song on Oprah's show the week prior to the release of her debut album.[40] "Fallin'", released as a single in April, went to No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100, and stayed atop the chart for six consecutive weeks.[40][49] Ebony magazine wrote that at the time "the music that was pumping on the airwaves was hip-hop and rap – not Alicia's unique blend of classical meets soul, meets hip-hop, meets, well, Alicia. What could have been a recipe for disaster ... turned into the opportunity of a lifetime."[32] Keys as an artist since her early days, Davis said, "does her own thing. She has set out her own vision. That's the way it is for artists of her ilk ... They don't try to fit in. They try to establish their own paths ... [she has] sure natural instinct and sure vision" and "a respect for musical history."[16][32]

Songs in A Minor, which included material that Columbia Records had rejected, was released on June 5, 2001,[38][40] to critical acclaim.[52][53][54] Musically, it incorporated classical piano in an R&B, soul and jazz-fused album.[55] Jam! described the music as "old-school urban sounds and attitude set against a backdrop of classical piano and sweet, warm vocals".[56] USA Today wrote that Keys "taps into the blues, soul, jazz and even classical music to propel haunting melodies and hard-driving funk".[57] Songs in A Minor would be "lauded for its mix of traditional soul values and city-girl coolness", wrote The Guardian.[27] PopMatters wrote that "Keys's Songs in A Minor is a testament to her desire (and patience) to create a project that most reflects her sensibilities as a 20-year-old woman and as a musical, cultural, and racial hybrid."[41]

Songs in A Minor debuted on the Billboard 200 chart at number one, selling 236,000 in its first week at retail.[14][40] On its second week, word of mouth and exposure from television performances was so significant that record stores requested another 450,000 copies.[35] The album went on to sell over 6.2 million copies in the United States and 12 million internationally.[58][59] It was certified six times Platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America.[60][61] Songs in A Minor established Keys's popularity both inside and outside of the United States where she became the best-selling new artist and R&B artist of the year.[40][62]

The album's second single, "A Woman's Worth", was released in February 2002 and peaked at seven on the Hot 100 and number three on Billboard's Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs; becoming her second top ten single on both charts.[63] Released in June, "How Come You Don't Call Me", Keys's cover of Prince's song, served as the album's third single, peaking at 59 on the Hot 100. The album's fourth single "Girlfriend" was released in the United Kingdom where it peaked at 82. The following year, the album was reissued as Remixed & Unplugged in A Minor, which included eight remixes and seven unplugged versions of the songs from the original.[citation needed]

Songs in A Minor received six Grammy Award nominations, including Record of the Year for "Fallin'". At the 2002 Grammy Awards, Keys won five awards: Song of the Year, Best Female R&B Vocal Performance, and Best R&B Song for "Fallin'", Best New Artist, and Best R&B Album.[64] Keys tied Lauryn Hill's record for the most Grammy wins for a female solo artist in a year.[15][65] That year, Keys wrote and produced the song "Impossible" for Christina Aguilera's album Stripped (2002), also providing background vocals and piano.[66][67] During the early 2000s, Keys also made small cameos in television series Charmed and American Dreams.[68]

2003–2005: The Diary of Alicia Keys and Unplugged[]

Keys followed up her debut with The Diary of Alicia Keys, which was released in December 2003. The album debuted at number one on the Billboard 200, selling over 618,000 copies its first week of release, becoming the largest first-week sales for a female artist in 2003.[69] It sold 4.4 million copies in the United States and was certified four times Platinum by the RIAA.[60][70] It sold eight million copies worldwide,[71] becoming the sixth-biggest-selling album by a female artist and the second-biggest-selling album by a female R&B artist.[72] The album's lead single, "You Don't Know My Name", peaked at number three on the Billboard Hot 100 and number one on the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart for eight consecutive weeks, her first Top 10 single in both charts since 2002's "A Woman's Worth". The album's second single, "If I Ain't Got You", was released in February 2004 and peaked at number 4 on the Billboard Hot 100 and number one on the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs for six weeks. The album's third single, "Diary", peaked at number 8 on the Billboard Hot 100 and number two on the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart, being their third consecutive Top 10 single in both charts. The album's fourth and final single, "Karma", which peaked at number 20 on the Billboard Hot 100 and number 17 on the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs, first release to fail to achieve top ten status on both charts. "If I Ain't Got You" became the first single by a female artist to remain on the Billboard Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart for over a year.[73][74][75][76][77] Keys also collaborated with recording artist Usher on the song "My Boo" from his 2004 album, Confessions (Special Edition). The song topped the Billboard Hot 100 for six weeks and Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs for three weeks, became her first number-one single on the Hot 100 since 2001's "Fallin'". Keys won Best R&B Video for "If I Ain't Got You" at the 2004 MTV Video Music Awards; she performed the song and "Higher Ground" with Lenny Kravitz and Stevie Wonder.[78][79]

While attending the Cannes Film Festival in May 2004, it was announced that Keys intended to make her film debut in a biopic about biracial piano prodigy Philippa Schuyler.[80] The film was to be co-produced by Halle Berry and Marc Platt.[81] September 25, Alicia Keys headlined the Wall of Hope concert on the Northern Gate Juyongguan section of the Great Wall of China, commemorating the 20th anniversary of the Great Wall of China's restoration project that was part of a series of benefit concerts.[82][83][7]

Later that year, Keys released her novel Tears for Water: Songbook of Poems and Lyrics, a collection of unreleased poems from her journals and lyrics. The title derived from one of her poems, "Love and Chains" from the line: "I don't mind drinking my tears for water."[84] She said the title is the foundation of her writing because "everything I have ever written has stemmed from my tears of joy, of pain, of sorrow, of depression, even of question".[85] The book sold over US$500,000 and Keys made The New York Times bestseller list in 2005.[23][86] The following year, she won a second consecutive award for Best R&B Video at the MTV Video Music Awards for the video "Karma".[87] Keys performed "If I Ain't Got You" and then joined Jamie Foxx and Quincy Jones in a rendition of "Georgia on My Mind", the Hoagy Carmichael song made famous by Ray Charles in 1960 at the 2005 Grammy Awards.[88] That evening, she won four Grammy Awards: Best Female R&B Vocal Performance for "If I Ain't Got You", Best R&B Song for "You Don't Know My Name", Best R&B Album for The Diary of Alicia Keys, and Best R&B Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocals" for "My Boo" with Usher.[89]

Keys performed and taped her installment of the MTV Unplugged series in July 2005 at the Brooklyn Academy of Music.[90] During this session, Keys added new arrangements to her original songs and performed a few choice covers.[91] The session was released on CD and DVD in October 2005. Simply titled Unplugged, the album debuted at number one on the U.S. Billboard 200 chart with 196,000 units sold in its first week of release.[92] The album sold one million copies in the United States, where it was certified Platinum by the RIAA, and two million copies worldwide.[60][68][93] The debut of Keys's Unplugged was the highest for an MTV Unplugged album since Nirvana's 1994 MTV Unplugged in New York and the first Unplugged by a female artist to debut at number one.[62] The album's first single, "Unbreakable", peaked at number 34 on the Billboard Hot 100 and number four on the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs.[94] It remained at number one on the Billboard Hot Adult R&B Airplay for 11 weeks.[95] The album's second and final single, "Every Little Bit Hurts", was released in January 2006, it failed to enter the U.S. charts.

Keys opened a recording studio in Long Island, New York, called The Oven Studios, which she co-owns with her production and songwriting partner Kerry "Krucial" Brothers.[96] The studio was designed by renowned studio architect John Storyk of , designer of Jimi Hendrix' Electric Lady Studios. Keys and Brothers are the co-founders of KrucialKeys Enterprises, a production and songwriting team who have assisted Keys in creating her albums as well as creating music for other artists.[97]

2006–2008: Film debut and As I Am[]

In 2006, Keys won three NAACP Image Awards, including Outstanding Female Artist and Outstanding Song for "Unbreakable".[98] She also received the Starlight Award by the Songwriters Hall of Fame.[99] In October 2006, she played the voice of Mommy Martian in the "Mission to Mars" episode of the children's television series The Backyardigans, in which she sang an original song, "Almost Everything Is Boinga Here".[100] That same year, Keys nearly suffered a mental breakdown. Her grandmother had died and her family was heavily dependent on her. She felt she needed to "escape" and went to Egypt for three weeks. She explained: "That trip was definitely the most crucial thing I've ever done for myself in my life to date. It was a very difficult time that I was dealing with, and it just came to the point where I really needed to—basically, I just needed to run away, honestly. And I needed to get as far away as possible."[101]

Keys made her film debut in early 2007 in the crime film Smokin' Aces, co-starring as an assassin named Georgia Sykes opposite Ben Affleck and Andy García. Keys received much praise from her co-stars in the film; Ryan Reynolds called her "so natural" and said she would "blow everybody away." Smokin' Aces was a moderate hit at the box office, earning $57,103,895 worldwide during its theatrical run.[102][103] In the same year, Keys earned further praise for her second film, The Nanny Diaries, based on the 2002 novel of the same name, where she co-starred alongside Scarlett Johansson and Chris Evans. The Nanny Diaries had a hit moderate performance at the box office, earning only $44,638,886 worldwide during its theatrical run.[104] She also guest starred as herself in the "One Man Is an Island" episode of the drama series Cane.[105]

Keys released her third studio album, As I Am, in November 2007; it debuted at number one on the Billboard 200, selling 742,000 copies in its first week. It gained Keys her largest first week sales of her career and became her fourth consecutive number one album, tying her with Britney Spears for the most consecutive number-one debuts on the Billboard 200 by a female artist.[106][107] The week became the second-largest sales week of 2007 and the largest sales week for a female solo artist since singer Norah Jones' album Feels like Home in 2004.[108] The album has sold three million copies in the United States and has been certified three times Platinum by the RIAA.[109][110] It has sold five million copies worldwide.[111] Keys received five nominations for As I Am at the 2008 American Music Award and ultimately won two.[112] The album's lead single, "No One", peaked at number one on the Billboard Hot 100 for five consecutive weeks and Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs for ten consecutive weeks, became her first number-one single on the Hot 100 since 2004's "My Boo" and becoming Keys's third and fifth number-one single on each chart, respectively.[113] The album's second single, "Like You'll Never See Me Again", was released in late 2007 and peaked at number 12 on the Billboard Hot 100 and number one on the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs for seven consecutive weeks. From October 27, 2007, when "No One" reached No. 1, through February 16, 2008, the last week "Like You'll Never See Me Again" was at No. 1, the Keys was on top of the chart for 17 weeks, more consecutive weeks than any other artist on the Hot R&B/Hip/Hop Songs chart.[114] The album's third single, "Teenage Love Affair", which peaked at number 54 on the Billboard Hot 100 and number three on the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs.[114] The album's fourth and final single, "Superwoman", which peaked at number 82 on the Billboard Hot 100 and number 12 on the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs.[114][115]

"No One" earned Keys the awards for Best Female R&B Vocal Performance and Best R&B Song at the 2008 Grammy Awards.[116] Keys opened the ceremony singing Frank Sinatra's 1950s song "Learnin' the Blues" as a "duet" with archival footage of Sinatra in video and "No One" with John Mayer later in the show.[117] Keys also won Best Female R&B Artist during the show.[118] She starred in "Fresh Takes", a commercial micro-series created by Dove Go Fresh, which premiered during The Hills on MTV from March to April 2008. The premiere celebrated the launch of new Dove Go Fresh.[119] She also signed a deal as spokesperson with Glacéau's VitaminWater to endorse the product, and was in an American Express commercial for the "Are you a Cardmember?" campaign.[120][121] Keys, along with The White Stripes' guitarist and lead vocalist Jack White, recorded the theme song to Quantum of Solace, the first duet in Bond soundtrack history.[122] In 2008, Keys was ranked in at number 80 the Billboard Hot 100 All-Time Top Artists.[123] She also starred in The Secret Life of Bees[124] Her role earned her a nomination for Outstanding Supporting Actress in a Motion Picture at the NAACP Image Awards.[125] She also received three nominations at the 2009 Grammy Awards and won Best Female R&B Vocal Performance for "Superwoman".[126]

In an interview with Blender magazine, Keys allegedly said "'Gangsta rap' was a ploy to convince black people to kill each other, 'gangsta rap' didn't exist" and went on to say that it was created by "the government". The magazine also claimed she said that Tupac Shakur and The Notorious B.I.G. were "essentially assassinated, their beefs stoked by the government and the media, to stop another great black leader from existing".[20] Keys later wrote a statement clarifying the issues and saying her words were misinterpreted.[127] Later that year, Keys was criticized by anti-smoking campaigners after billboard posters for her forthcoming concerts in Indonesia featured a logo for the A Mild cigarette brand sponsored by tobacco firm Philip Morris. She apologized after discovering that the concert was sponsored by the firm and asked for "corrective actions". In response, the company withdrew its sponsorship.[128]

2009–2011: The Element of Freedom, marriage and motherhood[]

In 2009, Keys approached Clive Davis for permission to submit a song for Whitney Houston's sixth studio album I Look to You. She subsequently co-wrote and produced the single "Million Dollar Bill" with record producer Swizz Beatz.[129] Months later, she was featured on rapper Jay-Z's song "Empire State of Mind" which was the lead single from his eleventh studio album The Blueprint 3. The song was a commercial and critical success, topping the Billboard Hot 100, becoming her fourth number-one song on that chart.[130] Additionally, it won Grammy Awards for 'Best Rap/Sung Collaboration and 'Best Rap Song' the following year, among a total of five nominations.[131] The following month, the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers honored Keys with the Golden Note Award, an award given to artists "who have achieved extraordinary career milestones".[132] She collaborated with Spanish recording artist Alejandro Sanz for "Looking for Paradise", which topped the Billboard Hot Latin Songs chart, this was Keys's first number one on all three charts, which also made her the first African-American of non-Hispanic origin to reach #1 on the Hot Latin Tracks.[133]

Keys released her fourth studio album, The Element of Freedom, in December 2009.[134] It debuted at number two on the Billboard 200, selling 417,000 copies in its first week.[135] As part of the promotional drive for the album, she performed at the Cayman Islands Jazz Festival on December 5, the final night of the three-day festival which would be broadcast on BET.[136] It was preceded by the release of its lead single "Doesn't Mean Anything" which peaked at sixty on the Hot 100, and fourteen on Billboard's Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs.[134][137] Keys was ranked as the top R&B recording artist of the 2000–2009 decade by Billboard magazine and ranked at number five as artist of the decade, while "No One" was ranked at number six on the magazine's top songs of the decade.[138][139][140] In the United Kingdom, The Element of Freedom became Keys's first album to top the UK Albums Chart.[141] The album's second single, "Try Sleeping with a Broken Heart", was released in November and peaked at number twenty-seven on the Hot 100 and number two on the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart.[137] The album's third single "Put It in a Love Song" featured recording artist Beyoncé. In February 2010, Keys released the fourth single, "Empire State of Mind (Part II) Broken Down" peaked at fifty-five on the Hot 100 and seventy-six on the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart.[137] In May, "Un-Thinkable (I'm Ready)" featuring rapper Drake was released as the album's fifth single. While only peaking at twenty-one on the Billboard Hot 100, it topped the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs for twelve consecutive weeks. The song became the album's most successful single; Keys eighth number one on the chart;[137] and Key's first number one song in five years. The album's sixth and final single, "Wait Til You See My Smile", was released in December 2010 in the United Kingdom.

In May 2010, a representative for Keys and Swizz Beatz confirmed that they were engaged and expecting a child together.[142] Keys and Beatz had a wedding celebration near the Mediterranean Sea on July 31, 2010.[143] On October 14, 2010, Keys gave birth to their first son, in New York City.[144] She recorded a song together with Eve called "Speechless", dedicated to her son.[145]

In June 2011, Songs in A Minor was re-released as deluxe and collector's editions in commemoration of its 10th anniversary.[146] To support the release, Keys embarked on a four-city promotional tour, titled Piano & I: A One Night Only Event With Alicia Keys, featuring only her piano. Keys is also set to co-produce the Broadway premiere of Stick Fly, which was opened[147] in December 2011.[148] At the end of June, a wax figure of Keys was unveiled at Madame Tussauds New York.[149] On September 26, 2011, was the premiere of Project 5, known as Five, a short film that marks the debut of Keys as a director. It is a documentary of five episodes that tell stories of five women who were victims of breast cancer and how it affected their lives. The production also has co-direction of the actresses Jennifer Aniston, Demi Moore and film director Patty Jenkins.[150] In October 2011, RCA Music Group announced it was disbanding J Records along with Arista Records and Jive Records. With the shutdown, Keys will release her future material on RCA Records.[151][152]

2012–2015: Girl on Fire[]

Keys released her fifth studio album Girl on Fire through RCA Records on November 27, 2012.[153] Keys has stated that she wants the album to "liberate" and "empower" fans.[154] The album's title track was released on September 4 as its lead single and peak number eleven on Billboard hot 100, the single was Keys's first top twenty own single on the chart since 2007 single "Like You'll Never See Me Again", she performed the song for the first time at the 2012 MTV Video Music Awards on September 6.[155][156] "Girl on Fire" is an uptempo anthem.[157] "Brand New Me" was released as the album's second single.[157] A softer ballad, it was noted as significantly different from the album's lead single.[157] Prior, two songs from Girl on Fire were released as promotion. The first was a song titled "New Day".[137] The song was later revealed to be the solo version of 50 Cent's lead single featuring Dr. Dre and Keys.[158][159] Another song, "Not Even the King" was uploaded to VEVO as a promotional song. Co-written by Scottish singer-songwriter Emeli Sandé, its lyrics talk about a rich love that couldn't be afforded by "the king".[160][161][162] Overall sales of the album were considerably lower than Keys's previous ones.

In September 2012, Keys collaborated with Reebok for her own sneakers collection.[163] In October 2012, Keys announced her partnership with Bento Box Entertainment's Bento Box Interactive to create an education mobile application titled "The Journals of Mama Mae and LeeLee" for iOS devices about the relationship between a young New York City girl and her wise grandmother. The app featured two of Keys's original songs, "Follow the Moon" and "Unlock Yourself".[164][165]

In January 2013, BlackBerry CEO Thorsten Heins and Keys officially unveiled the BlackBerry 10 mobile platform in New York City. Heins announced that Keys would be the company's new Global Creative Director.[166] In February 2013, Keys said she was hacked when her Twitter account tweeted tweets from an iPhone. In January 2014, BlackBerry said it will part ways with Keys at the end of that month.[167]

In March 2013, VH1 placed Keys at number 10 on their 100 Sexiest Artist list.[168] In June 2013, Keys's VH1 Storytellers special was released on CD and DVD.[169] Also, Keys and Maxwell were working on a "Marvin Gaye/Tammi Terrell" type of duets EP.[170] In 2013, she performed a duet with Italian singer Giorgia on the song "I Will Pray (Pregherò)". In November, the song was extracted as the second single from Giorgia's album Senza Paura and has been marketed in digital stores worldwide.[171] In 2014, Keys collaborated with Kendrick Lamar on the song "It's On Again" for The Amazing Spider-Man 2 soundtrack.[172] In July 2014, it was reported that Keys had changed management from Red Light Management's Will Botwin to Ron Laffitte and Guy Oseary at Maverick.[173]

On September 8, 2014, Keys uploaded the music video to a new song called "We Are Here" to her Facebook page, accompanied by a lengthy status update describing her motivation and inspiration to write the song.[174][175] It was released digitally the following week. Keys was also working with Pharrell Williams on her sixth studio album, first set for a 2015 release.[176][177] In an interview with Vibe, Keys described the sound of the album as "aggressive".[178] One of the songs on the album is called "Killing Your Mother".[179][180] In the same interview Keys revealed one of the songs on the album was titled "Killing Your Mother" with WWD, Keys discussed her first beauty campaign with Givenchy as the face of the new fragrance Dahlia Divin.[179] Keys also played the piano on a Diplo-produced song "Living for Love" which featured on Madonna's thirteenth studio album Rebel Heart (2015).[181] In November 2014, Keys announced that she is releasing a series of children's books.[182] The first book released is entitled Blue Moon: From the Journals of MaMa Mae and LeeLee.[183] Keys gave birth to her second child, son Genesis Ali Dean, on December 27, 2014.[184] In 2015 Keys performed at the BET Awards 2015 with The Weeknd. In September 2015, Swizz Beatz stated that Keys's sixth studio album will be released in 2016.[185] Keys played the character Skye Summers in the second season of Empire. She first appeared in the episode "Sinned Against", which aired November 25, 2015.[186]

2016–2018: Here and The Voice[]

On March 25, 2016, Keys was announced as a new coach on Season 11 of The Voice.[187] During The Voice finale, she came in third place with team member We' McDonald. On May 4, 2016, Keys released her first single in four years, entitled "In Common".[188] On May 28, 2016, Keys performed in the opening ceremony of 2016 UEFA Champions League Final in San Siro, Milan. The song topped Billboard's Dance Club Songs chart on October 15.[189] On June 20, 2016, World Refugee Day, Keys released the short film Let Me In, which she executive produced in conjunction with her We Are Here organization. The film is a reimagining of the refugee crisis as taking place in the United States.[190][191][192] On July 26, 2016, Keys performed at the 2016 Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia. In October 2016, she released a single from upcoming album Here called Blended Family (What You Do For Love) feat. A$AP Rocky.[193] On November 1, 2016, Keys unveiled her short film, "The Gospel," to accompany the LP.[194] Here was released on November 4, peaking at number 2 of the Billboard 200, becoming her seventh top 10 album.[195] It peaked at number-one on the R&B/Hip-Hop Albums chart, becoming her seventh chart topper.[196] On October 9, 2016, Keys performed a concert Here in Times Square in Times Square, New York. The performance was televised by BET on November 3, 2016.

In January 2017, she released the track "That's What's Up" that re-imagines the spoken word segment on the Kanye West song "Low Lights".[197] Keys returned for Season 12 of The Voice and won the competition with her artist Chris Blue, on May 23, 2017. In May 2017, in an interview with Entertainment Tonight, Keys announced that she was working on her seventh studio album, therefore she did not return for the thirteenth series of The Voice.[198] In a letter to her fans, on the 'As I Am' 10th Anniversary, she revealed that the album is almost ready.[199] In August 2017, she attended WE Day, an event of Canadian WE Charity organization.[200] On September 17, 2017, Keys performed at Rock in Rio, in a powerful and acclaimed performance.[201][202] On October 18, 2017, NBC announced that Keys would be returning to the series for the show's fourteenth season of The Voice alongside veterans Levine, Shelton, and new coach Kelly Clarkson. She placed in second place with her team member, Britton Buchanan. She will not return for the upcoming fifteenth season of The Voice.[203] On December 5, 2017, Hip hop artist Eminem revealed that Keys collaborated on the song "Like Home" for his ninth studio album Revival.[204] Keys also featured on the song "Morning Light" from Justin Timberlake's fifth studio album Man of the Woods (2018)[205] and on "Us", the third single from James Bay's second studio album Electric Light.[206]

On December 6, 2018, Keys spoke at the 13th Annual Billboard Women in Music event spotlighting her new non-profit named "She Is the Music".[207] As part of her address, Keys spoke briefly of the organization's efforts in creating an inclusive database of women in music and a partnership with Billboard to mentor young women interested in the music industry.[208] She created She is the Music upon learning that the number of women in popular music reached a six-year low in 2017, partnering with Jody Gerson, Sam Kirby and Ann Mincieli.[209][210]

2019–2020: Alicia, authorship[]

On January 15, 2019, Alicia Keys was announced as the host of the 61st Annual Grammy Awards. This was Keys's first time being the master of ceremonies for the event.[211] When Keys hosted the event on February 10, 2019, it became the first time a woman hosted the show in 14 years.[212] Keys's performance playing two pianos at the same time was declared one of the best moments of the 61st Annual Grammy Awards by Entertainment Tonight as well as the Los Angeles Daily News who also noted her fashion.[213][214] Keys dedicated the performance to those who have inspired her, including Scott Joplin and Hazel Scott, and drew the audience in by welcoming them to what she called "Club Keys".[215] Vox stated Alicia Keys was one of three reasons the 2019 Grammy Awards Ceremony was good, calling her the perfect host.[216]

In May 2019, Keys attended the 2019 Met Gala themed "Camp: Notes on Fashion" in New York City wearing a light aqua green sequined dress with hood alongside her husband Kasseem "Swizz Beatz" Dean who wore a dark green suit and black bow tie.[217][218] The next month, Keys performed at Pride Live's Stonewall Day Concert on June 28, 2019, wearing a white jumpsuit with the name of her upcoming song "Show Me Love" in multi-colored beads on the back of the jumpsuit.[219] Included in the songs she performed was her own song "Girl on Fire", the performance was part of a concert in honor of those who fought for gay (LGBT) community rights in the Stonewall Riots.[219] On July 26, 2019, Bloomberg News reported Keys and Beatz were avidly purchasing works by artist Tschabalala Self and that they decided to keep two of the pieces they bought and donate one to the Brooklyn Museum.[220] Less than a month later, Keys and Beatz revealed their plans for an art and music center including that they plan to have the center located in Macedon in upstate New York and to name it "Dean Collection Music & Art Campus".[218] Through the Dean Collection, they also collect notable artists such as Henry Taylor, Jordan Casteel, Kehinde Wiley, Toyin Ojih Odutola, Arthur Jafa, and Cy Gavin.[221]

Alicia Keys was announced as the buyer of the "Razor House" in the La Jolla community of San Diego, California in early September 2019.[222] In an interview with Billboard on December 5, 2019, Keys's recent move with her husband to the West Coast was briefly discussed.[223] Keys noted that she was enjoying having time to explore the more open landscape and the change of scenery, even finding the fog gorgeous.[223]

In September 2019, Keys released a new single, "Show Me Love" with Miguel. The accompanying music video starred actors Michael B. Jordan and Zoe Saldana.[224] The song impacted urban radio on September 24, 2019, as the first single from Keys's upcoming seventh studio album. Keys performed the track for the first time during her appearance at the 2019 iHeart Radio Music Festival in Las Vegas. The song was a commercial success on US Urban music charts and became Keys's first song to reach the Billboard Hot 100 since "Girl on Fire" in 2012; peaking at number 90 on November 22, 2019.[225] This success extended her record as the artist with the most number one singles on the Adult R&B Songs chart; reigning for 5 consecutive weeks. The song was atop this chart at the #1 position the weeks of December 14, December 21, and December 28 in 2019 and the weeks of January 4 and January 11 in 2020.[226] As of the week of January 11, 2020 "Show Me Love" had been on the Adult R&B Songs Chart (any position) for 16 weeks (the chart has 30 positions).[226] It also became Keys's 11th song to reach number one on the Adult R&B Songs chart.[227] It was followed by the release of the single "Time Machine" in November 2019. The music video for "Time Machine" was released the same month and noted for its retro roller rink setting and vibes.[228]

In December 2019 Keys was awarded the American Express Impact Award for her efforts to foster female artist growth and provide them with new opportunities through the non-profit she co-founded the year before and developed in 2019 named She Is the Music.[229] Keys received the award at the 14th Annual Women in Music Billboard event on December 12, 2019.[229]

"Fashion is such a representation of your energy, your own personal style and your expression of art."

—Keys[212]

On January 26, 2020, Alicia Keys hosted the 62nd Annual Grammy Awards for the second year in a row as announced on November 14, 2019.[230] In addition to hosting the event, Keys performed multiple times including a tribute with Boyz II Men to basketball star Kobe Bryant who died in a helicopter crash earlier that same day.[231] Keys also performed her new song "Underdog" with Brittany Howard backing the performance on acoustic guitar.[231] Keys's outfits for the 62nd Annual Grammy Awards Ceremony on January 26, 2020, were also praised by Today for their showstopping gorgeousness.[232] In addition to her outfits, Keys's stylish hair and on-point overall sense of style were recognized and covered by People.[212] Less than a week later, Keys presented a $20,000 scholarship to a teenager going to school in Texas alongside Ellen DeGeneres on "The Ellen DeGeneres Show" in support of his college education and in encouragement of him keeping his hair (long dreadlocks) intact for graduation.[233] Their hope is that the high school he's attending lets him walk at high school graduation without having to cut his dreadlocks to a shorter length.[233]

Keys's seventh studio album Alicia was originally scheduled to be released on May 15, 2020,[234] but then got postponed to September 18, 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[235][236] The new album features a four-square cover art piece showing Keys's head and shoulders from different views.[237] Alicia: The World Tour, Keys's first tour in seven years, was supposed to begin in Europe in June 2020, with the first planned stop on her tour Dublin on June 5.[238] After Europe, Alicia Keys would then have toured North America where she also planned to end her tour in Miami, Florida on September 22, 2020.[238]

Keys released her memoir More Myself: A Journey on March 31, 2020.

In September 2020, Alicia Keys also began a new beauty venture, Keys Soulcare, which first launched in the UK on Cult Beauty, a cosmetics retailer.[239][240] Keys Soulcare is a skincare and wellness brand that focuses on serious skincare and soul nurturing rituals that encourage self-love.[241][240]

On October 29, 2020, Alicia released "A Beautiful Noise" with Brandi Carlile to encourage Americans to get out and vote.[242] Alicia and Brandi performed "A Beautiful Noise" on Every Vote Counts: A Celebration of Democracy on CBS.[243] Keys and Carlile sat at separate pianos across from each other and alternated verses before coming together in harmony.[243] "A Beautiful Noise" was also included on the digital reissue of Keys's seventh studio album Alicia that was released on December 18, 2020.[244]

2021: Skincare line and debut 20th anniversary[]

Keys decided to celebrate the 20th anniversary of her first album, Songs in A Minor, with a performance at the 2021 Billboard Music Awards on May 23, 2021.[245] At the awards ceremony Michelle Obama praised Keys and the album as Obama introduced Keys. Keys's performance was a medley of songs from the album and she wore her hair in a braided hairstyle similar to what she wore when she debuted the album.[246]

In June 2021, InStyle announced Keys was expanding products in her skincare line Keys Soulcare to encompass face, neck, and body care products.[247] In an interview with The Guardian Keys shared that her anxiety surrounding what her skin looked like played a large role in developing her skin and body care offerings.[248] A five-year break from wearing make-up helped provide Keys with the time and perspective needed to develop the products she offers in Keys Soulcare.[249] Along with the launch of new products, Keys put forth a set of the tips, termed commandments, via Elle of things she does for spiritual and physical health and well-being.[250] With Shape magazine Keys shared a self-love ritual she does every morning that includes admiring herself in the morning for several minutes.[251]

Fostering the legacy of recently deceased rapper DMX, Keys appeared on his posthumous album Exodus featured in the song Hold Me Down.[252] In late June 2021, Keys was listed as one of the music artists pairing with Apple Fitness to distribute their music on Apple Watch with the aim of helping people achieve their exercise goals by providing music to listen to while working out.[253]

In July 2021, a collection of Prince's shoes were displayed at Paisley Park in Chanhassen, Minnesota. Keys supported Prince's fashion legacy by permitting a pair of shoes to be shown that Prince wore when he performed with Keys on his Welcome 2 America tour.[254]

Artistry[]

From the beginning of her career, Keys has been noted for being a multifaceted talent as a singer, songwriter, instrumentalist, arranger, and producer.[258] She achieved acclaim for her unique style and maturity as a classical musician and singer-songwriter. The Times wrote that Keys's debut album, Songs in A Minor, "spoke from a soul that seemed way beyond its years", and her follow up, The Diary of Alicia Keys, "confirmed her place in musical history".[8] The Seattle Times assessed that with her third album, As I Am, Keys continued showing diversity in her music and her "depth as a songwriter, singer and pianist."[259] USA Today, in a review of Songs in A Minor, commended Keys's "musical, artistic and thematic maturity" starting out her career.[260] The Japan Times regarded Keys's production of Songs in A Minor as displaying "the kind of taste and restraint that is rare in current mainstream R&B".[261] Billboard wrote that her debut "introduced a different kind of pop singer. Not only was she mean on the ivories, but she showed true musicianship, writing and performing her material", and Keys continued developing her artistry with subsequent albums.[262] Rolling Stone remarked that Keys broke into the music world as a singer "with hip-hop swagger, an old-school soul sound and older school (as in Chopin) piano chops", her appeal "bridging the generation gap".[263] On MSN's list of "Contemporary R&B, hip hop and rap icons", it was stated that Keys achieved prominence by "drawing from her classical technique as a pianist, enhanced by her ease as a multi-instrumentalist ... and songwriting steeped in her formal studies."[257]

Keys is also distinguished for being in control of her artistic output and image and having fought for creative independence since getting signed at 15 years old.[266] PopMatters called Keys an artist who "clearly has a fine sense of her creative talents and has struggled to make sure they are represented in the best way."[41] Rolling Stone wrote that, with her classical training, Keys "reintroduced the idea of a self-reliant (but still pop-friendly) R&B singer-songwriter – a type that stretches back to Stevie Wonder", crossing generational lines in the process.[267] Blender magazine expressed that Keys emerged as a "singer-songwriter-instrumentalist-producer with genuine urban swagger", and her largely self-produced second album showcased her growing "deftness and explorative verve".[268] In 2016, NPR stated that Keys "stood apart from pop trends while forging a remarkable career" and "sustained her focus on artistry".[39] MOBO described Keys as an accomplished pianist, singer, songwriter and producer who "has made a consistent and indelible contribution" to the music industry, her "unique approach" making classical music more accessible and "diffusing barriers between traditional and contemporary" while "keeping musical excellence at the core of her art".[269] In 2003, The Guardian wrote that Keys's largely self-created work is an "indication of how much power she wields", and described her as "an uncompromising artist" who "bears little resemblance" to contemporary stars.[14]

Keys has been praised for her expressive vocals and emotive delivery. In a review of Songs in A Minor, Jam! complimented her "crooning" and "warm" vocals as well as her belting "gospel-style".[255] CMJ New Music Monthly commended her "deep soulful voice and heartfelt delivery" of her songs.[270] Q magazine compared her vocal talent to Mary J Blige's and acknowledged her "sincerity" as "another plus" to her musical instincts.[271] PopMatters noted her "deep purple vocals" and considered that Keys is "less concerned about technical proficiency" and more interested in "rendering musical moments as authentic and visceral as possible".[41] The Guardian wrote that Keys "sings with devastating allure".[5] Reviewing a live performance, the Los Angeles Times wrote that Keys has a "commanding voice" and the "style and vision to convey the character and detail of the songs", and praised "the range and taste of her musical instincts".[45] NPR described her voice as "yearning and ready to break, even as it remains in control", considering it one of the elements integral to her music.[39] Rolling Stone wrote that her "dynamic" vocal tone extends "from a soft croon to a raspy, full-throated roar".[272] Keys has a three octave contralto vocal range.[269][273]

Keys has cited several artists as her inspirations, including Whitney Houston, John Lennon, Sade, Aretha Franklin, Bob Marley, Carole King, Prince, Nina Simone, Marvin Gaye, Quincy Jones, Donny Hathaway, Curtis Mayfield, Barbra Streisand, and Stevie Wonder.[277] An accomplished classical pianist, Keys incorporates piano into a majority of her songs.[5][38] Keys was described by New York Daily News as "one of the most versatile musicians of her generation".[73] Keys's music is influenced by vintage soul music rooted in gospel,[278] while she heavily incorporates classical piano with R&B, jazz, blues and hip hop into her music.[279] The Guardian noted that Keys is skilled at fusing the "ruff hip-hop rhythms she absorbed during her New York youth" into her "heartfelt, soulful R&B stylings".[5] The Songwriters Hall of Fame stated that Keys broke onto the music scene with "her unmistakable blend of soul, hip-hop, jazz and classical music".[280] She began experimenting with other genres, including pop and rock, in her third studio album, As I Am,[278][281][282] transitioning from neo soul to a 1980s and 1990s R&B sound with her fourth album, The Element of Freedom.[283][284] In 2005, The Independent described her musical style as consisting of "crawling blues coupled with a hip-hop backbeat, and soul melodies enhanced with her raw vocals".[285] The New York Daily News stated that her incorporation of classical piano riffs contributed to her breakout success.[73] Jet magazine stated she "thrives" by touching fans with "piano mastery, words and melodious voice".[286] In 2002, The New York Times wrote that on stage Keys "invariably starts with a little Beethoven" and "moves into rhythm-and-blues that's accessorized with hip-hop scratching, jazz scat-singing and glimmers of gospel."[38] Keys's debut album, PopMatters wrote, reflects her sensibilities as young woman and as a "musical, cultural, and racial hybrid."[41] NPR stated in 2016 that Keys's overall work consists of notable "diversity to style and form".[39] Salon wrote that the diversity of Keys's music is "representative of her own border-breaking background and also emblematic of the variety responsible for the excitement and energy of American culture."[287]

Keys's lyrical content has included themes of love, heartbreak, female empowerment, hope, her philosophy of life and struggles, inner city life experiences, and social and political commentary.[5][14][23][41][259][287][288] John Pareles of The New York Times noted that Keys presents herself as a musician first, and lyrically, her songs "plunge into the unsettled domain of female identity in the hip-hop era, determined to work their way through conflicting imperatives", while she plays multiple roles in her songs, expressing loyalty, jealousy, rejection, sadness, desire, fear, uncertainty, and tenacity.[38] Pareles considered in 2007 that Keys did not "offer private details in her songs" and that her musical compositions make up for a lack of lyrical refinement.[278][281] Gregory Stephen Tate of The Village Voice compared Keys's writing and production to 1970s music.[289] NPR described a few foundational elements in Key's music: "heartache or infatuation", a "tenderness and emotion made heavy with wisdom", a "patiently unfurling melody", and her "yearning" voice.[39] In 2016, referencing her sixth album, Here, Salon noted a "hypnotic tension" in Keys's lyrical expression and complimented her "sense of rhythmic timing" and socio-political consciousness.[287]

Legacy[]

Keys has been referred to as the "Queen of R&B" by various media outlets.[295] Time has listed her in its list of 100 most influential people twice. Journalist Christopher John Farley wrote: "Her musicianship raises her above her peers. She doesn't have to sample music's past like a DJ scratching his way through a record collection; she has the chops to examine it, take it apart and create something new and personal with what she has found" in 2005.[296] In 2017, Kerry Washington also wrote "Songs in A Minor infused the landscape of hip-hop with a classical sensibility and unfolded the complexity of being young, gifted, female and black for a new generation. Alicia became an avatar for millions of people, always remaining true to herself" in 2017.[297] Rolling Stone named Songs in A Minor as one of the "100 Greatest Albums",[298] and its single "Fallin'" in their "100 greatest songs" of the 2000s decade.[299]

VH1 have listed Keys in their "100 Greatest Artists of All Time",[300] 14th on "100 Greatest Women",[301] and 33rd on "50 Greatest Women of the Video Era" lists.[302] Considered a music icon,[306] Keys was placed at number 27 on Billboard's "35 Greatest R&B Artists of All Time" list in 2015.[307] The BET Honors honored Keys for her contributions to music with the Entertainment Award in 2008.[308] In 2009, ASCAP honored Keys with its Golden Note Award, presented "to songwriters, composers, and artists who have achieved extraordinary career milestones."[309][310] ASCAP President Paul Williams stated: "Since joining the ASCAP family at the age of 17, Alicia has grown into one of the most highly recognized and influential songwriter/performers of the past decade, whose artistry puts her in the league with many of her musical idols".[309] In 2011, Keys was honored at the Gala celebration of the 40th anniversary of Woodie King Jr.'s New Federal Theatre, as one of "13 individuals that changed the cultural life of our nation", including Sidney Poitier, Ntozake Shange, Ruby Dee, David Dinkins, and Malcolm Boyd.[311][312]

In 2015, The Recording Academy honored Keys in Washington D.C., with the Recording Artists' Coalition Award for "her artistry, philanthropy and her passion for creators' rights as a founding member of the Academy's brand-new GRAMMY Creators Alliance".[313] In 2018, she was honored by The Recording Academy's Producers & Engineers Wing for her "outstanding artistic contributions" and accomplishments.[314] The Recording Academy stated:

Keys exemplifies versatility, making her mark in the music world as a singer/songwriter and producer, as well as an actress, author, activist, and philanthropist. [...] her impact on music and culture reaches far beyond sales tallies. The New York native's message of female empowerment and her authentic songwriting process have made her an inspiration for women and aspiring creatives worldwide.[315]

In 2018, The National Music Publishers Association (NMPA) honored Keys with the Songwriter Icon award for her "credits as a music creator" and her "role as an inspirational figure to millions". NMPA president David Israelite wrote about Keys: "She's a songwriter icon, but she is also an icon of confidence and encouragement to all. Through her writing, performing, philanthropy, mentoring and advocacy for fair compensation for her fellow songwriters, she is a true force for good in our industry and beyond".[316]

Rolling Stone wrote that Keys was "something new" in contemporary popular music, "bridging the generation gap" with "hip-hop swagger, an old-school soul sound and older school (as in Chopin) piano chops."[263] Key's debut, Billboard stated, "introduced a different kind of pop singer. Not only was she mean on the ivories, but she showed true musicianship, writing and performing her material".[262] Barry Walters of Rolling Stone wrote that Keys "reintroduced the idea of a self-reliant (but still pop-friendly) R&B singer-songwriter – a type that stretches back to Stevie Wonder", crossing generational lines in the process.[267] On MSN's list of "Contemporary R&B, hip hop and rap icons", it was stated that Keys "set a high bar" from the outset of her career, "drawing from her classical technique as a pianist, enhanced by her ease as a multi-instrumentalist...and songwriting steeped in her formal studies."[257] AllMusic wrote that her debut "kicked off a wave of ambitious new neo-soul songsters" and "fit neatly into the movement of ambitious yet classicist new female singer/songwriters that ranged from the worldbeat-inflected pop of Nelly Furtado to the jazzy Norah Jones, whose success may not have been possible if Keys hadn't laid the groundwork".[317]

Keys transcends genres, The Recording Academy also stated, incorporating her "classical background into her music and including gospel, jazz, blues and vintage soul, rock, and pop influences", and she is "one of the most respected musicians of today."[303] Jet said that in 2001, Keys "ushered in a marriage between classical and soul music."[29] BBC's Babita Sharma stated in 2016 that Keys has had a significant impact "on the R&B-soul-jazz sound of the last two decades".[265] MOBO described Keys as an accomplished pianist, singer, songwriter and producer who is "responsible for the emergence of vintage R&B imbibed with a post-modernist twist where genres divinely melt" and "has made a consistent and indelible contribution" to the music industry, her "unique approach" making classical music more accessible and "diffusing barriers between traditional and contemporary".[269] ASCAP stated that Keys's "innovative and enduring contributions to rhythm & soul music have earned her an Extraordinary Place in American Popular Music."[310]

Keys has been credited with inspiring and influencing many artists,[40][318] including a younger generation of artists like Adele,[319] Rihanna,[320][321] Janelle Monáe,[322] H.E.R.,[323] Jessie Ware,[324][325] James Bay,[326] Ella Mai,[327] Wyvern Lingo,[318] Anuhea Jenkins,[328] Jorja Smith,[329][330] Lauren Jauregui,[331][332] Normani,[331] Alessia Cara,[333][334] Ruth-Anne Cunningham,[335] Lianne La Havas,[336][337][338] Heather Russell,[339] Grimes,[340] and Sophie Delila.[341]

Achievements[]

Keys is listed on the Recording Industry Association of America's best-selling artists in the United States, selling over 17.8 million albums and 21.9 million digital songs.[342] She has sold over 30 million albums worldwide.[343][344] Billboard ranked Keys as the fifth-most successful artist of the 2000s decade,[139] top R&B artist of the 2000s decade,[345] and placed her at number 10 in their list of Top 50 R&B/Hip-Hop Artists of the Past 25 Years.[346] Keys was the best-selling new artist and best-selling R&B artist of 2001.[62] She has attained 4 Billboard Hot 100 number-one singles from 9 top-ten singles.[347] She has also attained 8 Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs and Airplay number-one singles,[348][349] and set a Guinness World Record on the former in 2008, when she became the first artist to replace herself at number one with "No One" and "Like You'll Never See Me Again".[350] "No One" and "Empire State of Mind" are also amongst the list of best-selling singles worldwide.[351][352] Keys is one of three female artists included on Billboard magazine's list of the "Top 20 Hot 100 Songwriters, 2000–2011" for writing songs that topped the Billboard Hot 100 chart.[353]

Keys has earned numerous awards including 15 competitive Grammy Awards,[354] 17 NAACP Image Awards, 9 Billboard Music Awards and 7 BET Awards.[355] Keys received 5 Grammy Awards in 2002, becoming the second female artist to win as many in one night.[356] In 2005, Keys was awarded the Songwriters Hall of Fame Hal David Starlight Award, which honors "gifted songwriters who are at an apex in their careers and are making a significant impact in the music industry via their original songs".[17][280] That year, ASCAP awarded Keys Songwriter of the Year at its Rhythm & Soul Music Awards.[309] In 2007, she was a recipient of The Recording Academy Honors, which "celebrate outstanding individuals whose work embodies excellence and integrity and who have improved the environment for the creative community."[357] In 2014, Fuse ranked her as the thirteenth-most awarded musician of all time.[358]

Philanthropy and activism[]