American International Airways Flight 808

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2021) |

N814CK, the Kalitta Air McDonnell Douglas DC-8 involved in the accident | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | 18 August 1993 |

| Summary | Stall during steep bank due to pilot error caused by fatigue |

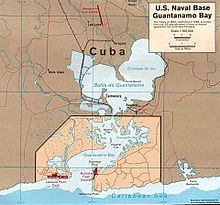

| Site | Leeward Point Field, Guantánamo Bay, Cuba 19°54′25″N 75°13′20″W / 19.90694°N 75.22222°WCoordinates: 19°54′25″N 75°13′20″W / 19.90694°N 75.22222°W |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | McDonnell Douglas DC-8-61(F) |

| Operator | American International Airways d/b/a Connie Kalitta Services |

| Registration | N814CK |

| Flight origin | Naval Station Norfolk Chambers Field, Norfolk, Virginia |

| Destination | Leeward Point Field, Guantánamo Bay, Cuba |

| Crew | 3 |

| Fatalities | 0 |

| Injuries | 3 |

| Survivors | 3 (all) |

American International Airways (AIA) Flight 808 was a cargo flight operated by American International Airways (now Kalitta Air) that crashed on August 18, 1993 while attempting to land at Leeward Point Field at the Guantánamo Bay Naval Base in Cuba. All 3 crew members on board survived with serious injuries.

Aircraft and Crew[]

The aircraft involved was N814CK, a McDonnell Douglas DC-8-61(F) manufactured in December 1969. Originally configured for passenger service, in 1991 it was sold to AIA and converted into a freighter. The aircraft had accumulated 43,947 flight hours and 18,829 flight cycles at the time of the crash. It was powered by four Pratt & Whitney JT3D-3B engines.[1]

54-year-old Captain James Chapo had joined AIA on February 11, 1991, and had 20,727 flight hours. He previously flew for Eastern Air Lines from 1966 to 1991. 49-year-old First Officer Thomas Curran joined AIA on November 3, 1992, and had 15,350 flight hours. He previously flew for Eastern Air Lines from 1968 to 1991 and served with the U.S. Navy from 1963 to 1968 during the Vietnam War. 35-year-old Flight Engineer David Richmond also joined AIA on February 11, 1991, and had 5,085 flight hours. He previously flew for Trans Continental Airlines from 1980 to 1991.[2]

The crew began their last shift before the crash near midnight on August 17, flying N814CK from Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport to Lambert International Airport in St. Louis, Missouri, Willow Run Airport in Ypsilanti, Michigan, and Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport in Atlanta, Georgia. The flight to Atlanta was supposed to be the end of the crew's shift. Flight 808 was originally scheduled for a separate crew in Miami, Florida using N808CK, another DC-8. This was canceled after N808CK suffered mechanical problems, so the accident crew were rescheduled to fly to Chambers Field in Norfolk, Virginia to pick up and deliver the freight bound for Guantánamo Bay and return to Atlanta.[2]

Crash[]

The flight took off from Norfolk at 14:13 EST. It was transporting mail and perishable food to the Guántanamo Bay Naval Base as per AIA's contract with the US Navy.[3] The flight was uneventful up to and during the arrival into Guantánamo Bay's terminal control area. The crew first made radio contact with air traffic control at 16:34. The controller reported instructions for approaching the airport, and also stated that the runway in use would be Runway 10. The crew requested for this to be changed to Runway 28, to which the controller accepted and issued further landing instructions. However, at 16:42, the crew requested again for the runway to be switched back to 10, which was also accepted.[1][2]

The plane had begun the turn too late, requiring it to make a steeper bank to align with the runway. A pilot of a Lockheed C-130 on the airport ramp stated "It looked to me as if he was turning to final rather late so it surprised me to see him at 30 to 40 degrees AOB [Angle of Bank] trying to make final. At 400 feet above ground level, he increased AOB to at least 60 degrees in an effort to make the runway and still overshooting."[2] At 200-300 feet above ground level, the right wing stalled. The nose pitched down as the wings rolled toward 90 degrees, and at 16:56, the aircraft struck level terrain 1,400 feet from the end of the runway.[1] The plane was destroyed by the impact and post-crash fire, and none of its cargo was salvaged. The cockpit had separated from the main wreckage and slid across the ground, coming to rest inverted with all 3 crew members alive inside, albeit with serious injuries.[2] Special permission was granted for a medical aircraft to overfly Cuban airspace to save time transporting the crew to hospital.[3]

Investigation[]

The National Transportation Safety Board investigated the accident. The cockpit voice recorder revealed that the flight crew had decided to land on Runway 10 "...for the heck of it to see how it is...", and planned to go-around and land on Runway 28 if they missed. During the approach to Runway 10, the air traffic controller told the crew to remain within the airspace designated by a strobe light mounted on the Cuban boarder fence. Unknown to the controller, this strobe light was inoperative on the day of the crash. Captain Chapo became fixated on trying to locate the strobe light, which led him to begin the turn too late, and failed to maintain his airspeed during the steep turn despite warnings from his other crew members.[1]

Having been on duty since midnight, Captain Chapo had been awake for 23.5 hours, First Officer Curran for 19 hours, and Flight Engineer Richmond for 21 hours at the time of the crash. A look back at the crew members sleep patterns in the 72 hours before the crash revealed that all 3 had accumulated a large sleep debt from working over long shifts. In the 3 days before the crash, Captain Chapo slept for a total of 15 hours, First Officer Curran for 18 hours, and Flight Engineer Richmond for 21.5 hours. Most of the crew's shifts were done at night, requiring them to attempt to sleep in the day, which disrupted their circadian rhythm. This aggravated the effects of fatigue on the crew, with Captain Chapo in particular observed suffering from various symptoms, including impaired judgement with his decision to land on Runway 10, his cognitive fixation on trying to locate the strobe light, the poor communication with his crew about their decreasing airspeed, and his slow reaction time in avoiding and recovering from the stall.[2][4]

The NTSB determined the probable causes to be:

"The impaired judgement, decision-making, and flying abilities of the captain and flight crew due to the effects of fatigue; the captain's failure to properly assess the conditions for landing and maintaining vigilant situational awareness of the airplane while manoeuvring onto final approach; his failure to prevent the loss of airspeed and avoid a stall while in the steep bank turn; and his failure to execute immediate action to recover from a stall."[2]

Aftermath[]

AIA Flight 808 was the first aviation accident where pilot fatigue was cited as a probable cause.[4] The NTSB issued a recommendation to the Federal Aviation Administration to review and update regulations on crew scheduling and duty time limits to incorporate the latest research into the effects of fatigue.[1]

Captain Chapo suffered back injuries that left him unable to go back to commercial flying. First Officer Curran's right leg was amputated, but he eventually went back to flying as a DC-8 Captain, and later became an NTSB investigator (2000–2001, and later, an Federal Aviation Administration inspector, B-767 APM, Delta CMO (2001–2021). After retiring from AIA in 2000. Flight Engineer Richmond also managed to recover and return to cargo flights, eventually becoming a captain for Frontier Airlines before retiring in 2018.

Dramatisation[]

The crash of Flight 808 was featured on the 19th season of Mayday, titled "Borderline Tactics".[5]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ a b c d e "ASN Aircraft accident McDonnell Douglas DC-8-61 N814CK Guantánamo NAS (NBW)". aviation-safety.net.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Aircraft Accident Report: Uncontrolled Collision with Terrain: American International Airways Flight 808" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board.

- ^ a b "CREW OF CRASHED JET IN CRITICAL CONDITION". Sun Sentinel.

- ^ a b Mark Rosekind. "Sleepless in America: The Deadly Cost of Fatigue in Transportation" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board.

- ^ American International Airways Flight 808 at IMDb

- Aviation accidents and incidents in 1993

- Accidents and incidents involving the Douglas DC-8

- Accidents and incidents involving cargo aircraft

- Aviation accidents and incidents in Cuba

- Guantanamo Bay Naval Base