American nationalism

American nationalism, or United States nationalism, is a form of civic nationalism, cultural nationalism, economic nationalism or ethnic nationalism[1] found in the United States.[2] Essentially, it indicates the aspects that characterize and distinguish the United States as an autonomous political community. The term often serves to explain efforts to reinforce its national identity and self-determination within their national and international affairs.[3]

All four forms of nationalism have found expression throughout the United States' history, depending on the historical period. American scholars such as Hans Kohn state that the United States government institutionalized a civic nationalism founded upon legal and rational concepts of citizenship, being based on common language and cultural traditions.[2] The Founding Fathers of the United States established the country upon classical liberal and individualist principles.

History[]

The United States traces its origins to the Thirteen Colonies founded by Britain in the 17th and early 18th century. Residents identified with Britain until the mid-18th century when the first sense of being "American" emerged. The Albany Plan proposed a union between the colonies in 1754. Although unsuccessful, it served as a reference for future discussions of independence.

Soon afterward, the colonies faced several common grievances over acts passed by the British Parliament, including taxation without representation. Americans were in general agreement that only their own colonial legislatures—and not Parliament in London—could pass taxes. Parliament vigorously insisted otherwise and no compromise was found. The London government punished Boston for the Boston Tea Party and the Thirteen Colonies united and formed the Continental Congress, which lasted from 1774 to 1789. Fighting broke out in 1775 and the sentiment swung to independence in early 1776, influenced especially by the appeal to American nationalism by Thomas Paine. His pamphlet Common Sense was a runaway best seller in 1776.[5] Congress unanimously issued a Declaration of Independence announcing a new nation had formed, the United States of America. American Patriots won the American Revolutionary War and received generous peace terms from Britain in 1783. The minority of Loyalists (loyal to King George III) could remain or leave, but about 80% remained and became full American citizens.[6] Frequent parades along with new rituals and ceremonies—and a new flag—provided popular occasions for expressing a spirit of American nationalism.[7]

The new nation operated under the very weak national government set up by the Articles of Confederation and most Americans put loyalty to their state ahead of loyalty to the nation. Nationalists led by George Washington, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison had Congress call a constitutional convention in 1787. It produced the Constitution for a strong national government which was debated in every state and unanimously adopted. It went into effect in 1789 with Washington as the first President.[8]

In an 1858 speech, future President Abraham Lincoln alluded to a form of American civic nationalism originating from the tenets of the Declaration of Independence as a force for national unity in the United States, stating that it was a method for uniting diverse peoples of different ethnic ancestries into a common nationality:

If they look back through this history to trace their connection with those days by blood, they find they have none, they cannot carry themselves back into that glorious epoch and make themselves feel that they are part of us, but when they look through that old Declaration of Independence they find that those old men say that "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal", and then they feel that moral sentiment taught in that day evidences their relation to those men, that it is the father of all moral principle in them, and that they have a right to claim it as though they were blood of the blood, and flesh of the flesh of the men who wrote the Declaration, and so they are. That is the electric cord in that Declaration that links the hearts of patriotic and liberty-loving men together, that will link those patriotic hearts as long as the love of freedom exists in the minds of men throughout the world.

— Abraham Lincoln, address to Chicagoan voters, July 10, 1858[9]

American Civil War[]

White Southerners increasingly felt alienated—they saw themselves as becoming second-class citizens as aggressive anti-slavery Northerners tried to end their ability to take slaves to the fast-growing western territories. They questioned whether their loyalty to the nation trumped their loyalty to their state and their way of life since it was so intimately bound up with slavery, whether they owned any slaves or not.[10] A sense of Southern nationalism was starting to emerge, though it was inchoate as late as 1860 when the election of Lincoln was a signal for most of the slave states in the South to secede and form their own new nation.[11] The Confederate government insisted the nationalism was real and imposed increasing burdens on the population in the name of independence and nationalism. The fierce combat record of the Confederates demonstrates their commitment to the death for independence. The government and army refused to compromise and were militarily overwhelmed in 1865.[12] By the 1890s, the white South felt vindicated through its belief in the newly constructed memory of the Lost Cause of the Confederacy. The North came to accept or at least tolerate racial segregation and disfranchisement of black voters in the South. The spirit of American nationalism had returned to Dixie.[13]

The North's triumph in the American Civil War marked a significant transition in American national identity. The ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment settled the basic question of national identity, such as the criteria for becoming a citizen of the United States. Everyone born in the territorial boundaries of the United States or those areas and subject to its jurisdiction was an American citizen, regardless of ethnicity or social status (indigenous people on reservations became citizens in 1924 while indigenous people off reservations had always been citizens).[16]

With a very fast growing industrial economy, immigrants were welcome from Europe, Canada, Mexico and Cuba and millions came. Becoming a full citizen was an easy process of filling out paperwork over a five-year span.[17]

However, new Asian arrivals were not welcome. Restrictions were imposed on most Chinese immigrants in the 1880s and informal restrictions on most Japanese in 1907. By 1924, it was difficult for any Asian to enter the United States, but children born in the United States to Asian parents were full citizens. The restrictions were ended on the Chinese in the 1940s and on other Asians in 1965.[18]

Contemporary United States[]

Nationalism and Americanism remain topics in the modern United States. Political scientist Paul McCartney, for instance, argues that as a nation defined by a creed and sense of mission Americans tend to equate their interests with those of humanity, which in turn informs their global posture.[19] In certain cases, it may be considered a form of ethnocentrism and American exceptionalism.

Due to the distinctive circumstances involved throughout history in American politics, its nationalism has developed in regards to both loyalty to a set of liberal, universal political ideals and a perceived accountability to propagate those principles globally. Acknowledging the conception of the United States as accountable for spreading liberal change and promoting democracy throughout the world's politics and governance has defined practically all of American foreign policy. Therefore, democracy promotion is not just another measure of foreign policy, but it is rather the fundamental characteristic of their national identity and political determination.[20]

The September 11 attacks of 2001 led to a wave of nationalist expression in the United States. This was accompanied by a rise in military enlistment that included not only lower-income Americans, but also middle-class and upper-class citizens.[21]

Varieties of American nationalism[]

In a paper in the American Sociological Review, "Varieties of American Popular Nationalism", sociologists Bart Bonikowski and Paul DiMaggio report on research findings supporting the existence of at least four kinds of American nationalists, including, groups which range from the smallest to the largest: (1) the disengaged, (2) creedal or civic nationalists, (3) ardent nationalists, and (4) restrictive nationalists.[22]

Bonikowski and Dimaggio's analysis of these four groups found that ardent nationalists made up about 24% of their study, and they comprised the largest of the two groups which Bonikowski and Dimaggio consider "extreme". Members of this group closely identified with the United States, were very proud of their country, and strongly associated themselves with factors of national hubris. They felt that a "true American" must speak English, and live in the U.S. for most of his or her life. Fewer, but nonetheless 75%, believe that a "true American" must be a Christian and 86% believe a "true American" must be born in the country. Further, ardent nationalists believed that Jews, Muslims, agnostics and naturalized citizens were something less than truly American. The second class which Bonikowski and DiMaggio considered "extreme" was the smallest of the four classes, because its members made up 17% of their respondents. The disengaged showed low levels of pride in the institutions of government and they did not fully identify themselves with the United States. Their lack of pride extended to American democracy, American history, the political equality in the U.S., and the country's political influence in the world. This group was the least nationalistic of all of the four groups which they identified.[22]

The two remaining classes were less homogeneous in their responses than the ardent nationalists and disengaged were. Restrictive nationalists had low levels of pride in America and its institutions, but they defined a "true American" in ways that were markedly "exclusionary". This group was the largest of the four, because its members made up 38% of the study's respondents. While their levels of national identification and pride were moderate, they espoused beliefs which caused them to hold restrictive definitions of who "true Americans" were, for instance, their definitions excluded non-Christians." The final group to be identified were creedal nationalists, whose members made up 22% of the study's respondents who were studied. This group believed in liberal values, was proud of the United States, and its members held the fewest restrictions on who could be considered a true American. They closely identified with their country, which they felt "very close" to, and were proud of its achievements. Bonikowski and Dimaggio dubbed the group "creedal" because their beliefs most closely approximated the precepts of what is widely considered the American creed.[22]

As part of their findings, the authors report that the connection between religious belief and national identity is a significant one. The belief that being a Christian is an important part of what it means to be a "true American" is the most significant factor which separates the creedal nationalists and the disengaged from the restrictive and ardent nationalists. They also determined that their groupings cut across partisan boundaries, and they also help to explain what they perceive is the recent success of populist, nativist and racist rhetoric in American politics.[22]

Donald Trump presidency[]

President Donald Trump was described as a nationalist[24] and he embraced the term himself.[25] Several officials within his administration, including former White House Chief Strategist Steve Bannon,[26] Senior Advisor to the President Stephen Miller,[26] Director of the National Trade Council Peter Navarro,[27] former Deputy Assistant to the President Sebastian Gorka,[26] Special Assistant to the President Julia Hahn,[28] former Deputy Assistant to the President for Strategic Communications Michael Anton,[29] Secretary of State Mike Pompeo,[30] Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross,[31] Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer,[32] former acting Director of National Intelligence Richard Grenell,[33] former National Security Advisor John R. Bolton[34] and former National Security Advisor Michael Flynn[35] were described as representing a "nationalist wing" within the federal government.[36]

In a February 2017 article in The Atlantic, journalist Uri Friedman described "populist economic nationalist" as a new nationalist movement "modeled on the 'populism' of the 19th-century U.S. President Andrew Jackson" which was introduced in Trump's remarks to the Republican National Convention in a speech written by Stephen Miller and Steve Bannon. Miller had adopted Senator Jeff Sessions' form of "nation-state populism" while working as his aide.[37] By September 2017, The Washington Post journalist Greg Sargent observed that "Trump's nationalism" as "defined" by Bannon, Breitbart, Miller and "the rest of the 'populist economic nationalist' contingent around Trump" was beginning to have wavering support among Trump voters.[38] Some Republican members of Congress have also been described as nationalists, such as Representative Steve King,[39] Representative Matt Gaetz,[40] Senator Tom Cotton[41] and Senator Josh Hawley.[42]

During the Trump era, commonly identified American nationalist political commentators included Ann Coulter,[43] Michelle Malkin,[44] Lou Dobbs,[45] Alex Jones,[46] Laura Ingraham,[43] Michael Savage,[47] Tucker Carlson[48] and Mike Cernovich.[49]

See also[]

- American ancestry

- American conservatism

- American exceptionalism

- American literary nationalism

- American nativism

- American neo-nationalism

- American patriotism

- Americanism

- Americanization

- Christian Patriot

- Emergency Quota Act

- Immigration Act of 1924

- Liberal nationalism

- Manifest Destiny

- Melting Pot

- National symbols of the United States

- New Nationalism (Theodore Roosevelt)

- Paleoconservatism

- Patriot movement

- Pax Americana

- Salad bowl (cultural idea)

- White nationalism

References[]

Notes

- ^

- Barbour, Christine & Wright, Gerald C. (January 15, 2013). Keeping the Republic: Power and Citizenship in American Politics, 6th Edition The Essentials. CQ Press. pp. 31–33. ISBN 978-1-4522-4003-9. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

Who Is An American? Native-born and naturalized citizens

- Shklar, Judith N. (1991). American Citizenship: The Quest for Inclusion. The Tanner Lectures on Human Values. Harvard University Press. pp. 3–4. ISBN 9780674022164. Retrieved December 17, 2012.

- Slotkin, Richard (2001). "Unit Pride: Ethnic Platoons and the Myths of American Nationality". American Literary History. 13 (3): 469–498. doi:10.1093/alh/13.3.469. S2CID 143996198. Retrieved December 17, 2012.

But it also expresses a myth of American nationality that remains vital in our political and cultural life: the idealized self-image of a multiethnic, multiracial democracy, hospitable to differences but united by a common sense of national belonging.

- Eder, Klaus & Giesen, Bernhard (2001). European Citizenship: Between National Legacies and Postnational Projects. Oxford University Press. pp. 25–26. ISBN 9780199241200. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

In inter-state relations, the American nation state presents its members as a monistic political body-despite ethnic and national groups in the interior.

- Petersen, William; Novak, Michael & Gleason, Philip (1982). Concepts of Ethnicity. Harvard University Press. p. 62. ISBN 9780674157262. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

To be or to become an American, a person did not have to be of any particular national, linguistic, religious, or ethnic background. All he had to do was to commit himself to the political ideology centered on the abstract ideals of liberty, equality, and republicanism. Thus the universalist ideological character of American nationality meant that it was open to anyone who willed to become an American.

- Hirschman, Charles; Kasinitz, Philip & Dewind, Josh (November 4, 1999). The Handbook of International Migration: The American Experience. Russell Sage Foundation. p. 300. ISBN 978-1-61044-289-3.

- Halle, David (July 15, 1987). America's Working Man: Work, Home, and Politics Among Blue Collar Property Owners. University of Chicago Press. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-226-31366-5.

The first, and central, way involves the view that Americans are all those persons born within the boundaries of the United States or admitted to citizenship by the government.

- Barbour, Christine & Wright, Gerald C. (January 15, 2013). Keeping the Republic: Power and Citizenship in American Politics, 6th Edition The Essentials. CQ Press. pp. 31–33. ISBN 978-1-4522-4003-9. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Motyl 2001, p. 16.

- ^ Miscevic, Nenad (March 31, 2018). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved March 31, 2018 – via Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Wills, Inventing America, 348.

- ^ Loughran, Trish (March 1, 2006). "Disseminating Common Sense: Thomas Paine and the Problem of the Early National Bestseller". American Literature. 78 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1215/00029831-78-1-1. ISSN 0002-9831.

- ^ Savelle, Max (1962). "Nationalism and Other Loyalties in the American Revolution". The American Historical Review. 67 (4): 901–923. doi:10.2307/1845245. JSTOR 1845245.

- ^ Waldstreicher, David (1995). "Rites of Rebellion, Rites of Assent: Celebrations, Print Culture, and the Origins of American Nationalism". The Journal of American History. 82 (1): 37–61. doi:10.2307/2081914. JSTOR 2081914.

- ^ Larson, Edward J. (2016) George Washington, Nationalist. University of Virginia Press

- ^ Address to Chicagoan voters (July 10, 1858); quoted in Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (1953), vol 2 p. 501.

- ^ Kohn, Hans (1961). The Idea of Nationalism: A Study in Its Origins and Background. Macmillan. OCLC 1115989.

- ^ McCardell, John (1979). The Idea of a Southern Nation: Southern Nationalists and Southern Nationalism, 1830–1860. ISBN 978-0393012415. OCLC 4933821.

- ^ Quigley, Paul (2012) Shifting Grounds: Nationalism and the American South, 1848–1865

- ^ Foster, Gaines M. (1988) Ghosts of the Confederacy: Defeat, the Lost Cause and the Emergence of the New South, 1865–1913

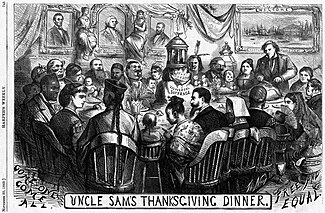

- ^ Kennedy, Robert C. (November 2001). "Uncle Sam's Thanksgiving Dinner, Artist: Thomas Nast". On This Day: HarpWeek. The New York Times Company. Archived from the original on November 23, 2001. Retrieved November 23, 2001.

- ^ Walfred, Michele (July 2014). "Uncle Sam's Thanksgiving Dinner: Two Coasts, Two Perspectives". Thomas Nast Cartoons. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved March 5, 2016.

- ^ Larsen, Charles E. (1959). "Nationalism and States' Rights in Commentaries on the Constitution after the Civil War". The American Journal of Legal History. 3 (4): 360–369. doi:10.2307/844323. JSTOR 844323.

- ^ Archdeacon, Thomas J. (2000) European Immigration from the Colonial Era to the 1920s: A Historical Perspective

- ^ Lee, Erika (2007). "The "Yellow Peril" and Asian Exclusion in the Americas". Pacific Historical Review. 76 (4): 537–562. doi:10.1525/phr.2007.76.4.537.

- ^ McCartney, Paul (August 28, 2002). The Bush Doctrine and American Nationalism. Annual meeting of the American Political Science Association. American Political Science Association. McCartney-2002. Archived from the original on August 12, 2007. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- ^ Monten, Jonathan (2005) "The Roots of the Bush Doctrine: Power, Nationalism, and Democracy Promotion in U.S. Strategy" International Security v.29 n.4 pp.112-156

- ^ "The Demographics of Military Enlistment After 9/11".

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Bonikowski, Bart and DiMaggio, Paul (2016) "Varieties of American Popular Nationalism". American Sociological Review, v.81 n.5 pp.949–980.

- ^ Kemmelmeier, Marcus (December 2008). "Sowing Patriotism, But Reaping Nationalism? Consequences of Exposure to the American Flag". Political Psychology. 29 (6): 859–879. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2008.00670.x.

- ^ "Trump visits Poland and not everyone is happy about it". USA Today. July 3, 2017.

- ^ "Trump: I Am A Nationalist In A True Sense". RealClearPolitics. February 27, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Trump pressured to dump nationalist wing". The Hill. August 15, 2017.

- ^ Sherman, Gabriel. ""I Have Power": Is Steve Bannon Running for President?". vanityfair.com. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- ^ "Breitbart writer expected to join White House staff". Politico. January 22, 2017.

- ^ "The Populist Nationalist on Trump's National Security Council". The Atlantic. March 24, 2017.

- ^ "'Congressman from Koch' Mike Pompeo tapped to replace Tillerson at State Department". Marketwatch. March 13, 2018.

- ^ "Trump expected to tap billionaire investor Wilbur Ross for commerce secretary". The Washington Post. November 24, 2016.

- ^ "The Little-Known Trade Adviser Who Wields Enormous Power in Washington". The New York Times. March 8, 2018.

- ^ "Grenell to join Trump campaign". Politico. May 26, 2020.

- ^ "US nationalist policymakers take hold of foreign policy". Financial Times. March 23, 2018.

- ^ "The Alt-Right and Glenn Greenwald Versus H.R. McMaster". New York Magazine. August 8, 2017.

- ^ "The White House struggle between Stephen Bannon and H.R. McMaster is apparently coming to a head". The Week. August 14, 2017.

- ^ Friedman, Uri (February 27, 2017). "What is a populist? And is Donald Trump one?". The Atlantic. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- ^ Sargent, Greg (September 15, 2017). "Trump's top supporters are in a full-blown panic. They're right to be afraid". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- ^ "Steve King ingests the poison of nationalist ideology". Washington Examiner. March 13, 2017.

- ^ "'It's a horror film': Matt Gaetz warns of Democratic rule at Republican convention". Tampa Bay Times. August 25, 2020.

- ^ https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2017/02/07/how-tom-cotton-emerged-as-one-of-trumpisms-leading-voices/

- ^ "Polishing the Nationalist Brand in the Trump Era". The New York Times. July 19, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brownstein, Ronald (April 16, 2017). "Why Trump's Agenda Is Tilting in a More Conventional Direction". The Atlantic.

- ^ "Free speech continues to be squelched from left and right". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Atlanta. January 16, 2020.

- ^ "Donald Trump 'Cherishes' Lou Dobbs So Much He Puts Him on Speakerphone for Oval Office Meetings". The Daily Beast. October 26, 2019.

- ^ "Donald Trump still calls Alex Jones for advice, claims the InfoWars founder and far right conspiracy theorist". The Independent. February 23, 2017.

- ^ "Misunderstood Nationalist — Understanding Michael Savage". National Summary. Archived from the original on January 22, 2008. Retrieved June 24, 2009.

- ^ Coppins, McKay (February 23, 2017). "Tucker Carlson: The Bow-Tied Bard of Populism". The Atlantic.

- ^ Stack, Liam (April 5, 2017). "Who Is Mike Cernovich? A Guide". The New York Times.

Further reading[]

- Arieli, Yehoshua (1964) Individualism and Nationalism in American Ideology. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Birkin, Carol (2017) A Sovereign People: The Crises of the 1790s and the Birth of American Nationalism. Basic Books, ISBN 978-0-465-06088-7.

- Faust, Drew G. (1988) The Creation of Confederate Nationalism: Ideology and Identity in the Civil War South. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press.

- Kramer, Lloyd S. (2011) Nationalism in Europe and America: Politics, Cultures, and Identities Since 1775. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807872000

- Lawson, Melinda (2002) Patriot Fires: Forging a New American Nationalism in the Civil War North. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas.

- Li, Qiong, and Marilynn Brewer (2004) "What Does It Mean to Be an American? Patriotism, Nationalism, and American Identity After September 11." Political Psychology. v.25 n.5 pp. 727–39.

- Motyl, Alexander J. (2001). Encyclopedia of Nationalism, Volume II. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-227230-1.

- Maguire, Susan E. (2016) "Brother Jonathan and John Bull build a nation: the transactional nature of American nationalism in the early nineteenth century." National Identities v.18 n.2 pp. 179–98.

- Mitchell, Lincoln A. (2016) The Democracy Promotion Paradox. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution. ISBN 9780815727026

- Quigley, Paul (2012) Shifting Grounds: Nationalism and the American South, 1848-1865. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199735488

- Schildkraut, Deborah J. 2014. "Boundaries of American Identity: Evolving Understandings of “Us”." Annual Review of Political Science

- Staff (December 13, 2016) "How similar is America in 2016 to Germany in 1933". Boston Public Radio

- Staff (December 20, 2005). "French anti-Americanism: Spot the difference". The Economist.

- Trautsch, Jasper M. (September 2016) "The origins and nature of American nationalism," National Identities v.18 n.3 pp. 289–312.

- Trautsch, Jasper M. (2018) The Genesis of America; U.S. Foreign Policy and the Formation of National Identity, 1793 - 1815. Cambridge

- Waldstreicher, David (1997) In the Midst of Perpetual Fetes: The Making of American Nationalism, 1776–1820. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press

- Zelinsky, Wilbur (1988) Nation into State: The Shifting Symbolic Foundations of American Nationalism. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

External links[]

Media related to American nationalism at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to American nationalism at Wikimedia Commons

- American nationalism

- American culture

- Political terminology of the United States