Ancient furniture

Ancient furniture was made of many different materials, including reeds, wood, stone, metals, straws, and ivory. It could also be decorated in many different ways. Sometimes furniture would be covered with upholstery, upholstery being padding, springs, webbing, and leather. Features which would mark the top of furniture, called finials, were common. To decorate furniture, contrasting pieces would be inserted into depressions in the furniture. This practice is called inlaying.

It was common for ancient furniture to have religious or symbolic purposes. The Incans had chacmools which were dedicated to sacrifice. Similarly, in Dilmun they has sacrificial altars. In many civilizations, the furniture depended on wealth. Sometimes certain types of furniture could only be used by the upper class citizens. For example, in Egypt, thrones could only be used by the rich. Sometimes the way the furniture was decorated depended on wealth. For example, in Mesopotamia tables would be decorated with expensive metals, chairs would be padded with felt, rushes, and upholstery. Some chairs had metal inlays.

Mesopotamia[]

Sumeria[]

Materials[]

Most Mesopotamian furniture was constructed out of wood, reeds, and other perishable materials.[1] Wood was coomon and important in Sumerian furniture. Sumerian records mention a type of wood named Halub wood. It is mentioned in Sumerian documents as a kind of wood used to make beds, bedframes, furniture legs, chairs, foot-stools, baskets, containers, drinking vessels, and other prestigious goods.[2] Timber, despite the fact that it had to be imported from Lebanon, was used in carpentry.[3] Cuneiform records also mention woods called kusabku and Sulum Meluhi wood. Kusakbu wood could be used for inlaying thrones with lapis lazuli. [4]This likely makes it teak wood. Although some theories suggest it was actually Mangrove wood. Sulum Meluhi may have been ebony, or it could have been roosewood, as no ebony has been found at archaeological sites. If it was Rosewood it would have been imported from Harrapa. Date palm was another type of wood used in Sumerian furniture. According to the Sumerians themselves, they imported it form Meluhha. This is doubted by academics, as date palm grew in southern Mesopotamia, implying that they imported something else, which was similar to date palm. Bamboo or Sugarcane from Magan was used by Sumerians. They described it as "reeds bundled together to look like wood."[5] Although wood was common, other materials were used for furniture. Furniture legs would be decorated with metal rings and luxury pieces in Akkad would have finials and animal feet and legs.[6]

Chairs[]

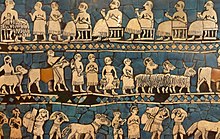

Common furniture in Mesopotamia included beds, stools, and chairs made of palmwood or woven reeds.[7] Wealthy citizens would have chairs padded with felt, rushes, and leather upholstery.[8] The most expensive chairs were inlaid with bronze, copper, silver, and gold. In Akkad, the finest furniture would be inlaid or overlaid with panels and ornaments of metals, gemstones, ivory, faience. Chairs would also have brightly colored wooden and ivory finials depicting arms and bull's heads.[8] Sometimes these finials would be cast-bronze or carved-bone. Oftentimes the chairs would have bronze panels that had images of griffins and winged deities carved into them. The Royal Standard of Ur showcases the king of Ur on a low-back chair with animal legs. The seats depicted on the Royal Standard were likely made of Rush and Cane. During this period of Sumerian history chairs were not used by the majority of people. Most people simply sat on the floor. Low-backed chairs with curved or flat seats and turned legs were incredibly common in the Akkadian Empire.

Beds[]

Although there were beds in Sumeria, most people slept on the floor rather than beds.[9] The Sumerian bed was a wooden bed on a wooden frame. The bed frame was a tall head-board decorated with pictures of birds and flowers.[10] Sometimes the bed's leg would be inlaid with precious metals and shaped to look like animal's paws.[2] Some Akkadian beds had ox-hoof feet.[7] The upper class in Sumeria would use leather, cloth strips, carefully woven reeds to form the sleeping platform.[11] In Akkad, beds were fashioned by stretching ropes across a wooden frame to support a mattress or sleeping bag.[7] Wealthy Mesopotamians had beds with wooden frames and mattresses stuffed with cloth, goat's hair, wool, or linen. The marriage bed was an important kind of bed in Sumeria. After a marriage the couple would engage in sexual intercourse in the bed. If the bride to not get pregnant, the marriage could be invalidated.[11]

Mats[]

People would cover their floors with mats woven from reeds, skin rugs, and woolen hangings.[12][13] [14] During the early parts of Sumerian history, reed mats would be fastened to sticks and stuck into the ground or houses. Sometimes reed-mats were used to make houses.[15] The roofs of certain houses would be flat mud spread out over mats. These mats would be supported by cross beams. Another way of supporting these huts was to tie bundles of reeds together and bend the top inwards. These bundles would serve as arches.[16] Some food would have been sprayed over mats. For example, one Sumerian text explains that a person should spread cooked mash over reed mats. Other Sumerian texts talk about covering chariots in reed mats.[17] Mats could have also been used to cover skeletons.[18]

Household Furniture[]

It was uncommon most houses to have a lot of furniture as most furniture was reserved for the wealthy.[10][19]The majority of furniture in Sumeria was made of wicker wood.[20] Storage chests were one type of furniture which was common. Chests could be made from reed or wood. Some were elaborately carved.[13][21][22] Stools, tables, and reed mats were also common. Tables were used to hold meals or belongings. Wealthy Mesopotamians would decorate their tables with metals. Aside from chests and tables people would use Baskets made of reed, wicker wood, or straw and bins used of sun-dried clay, palmwood, or reeds for storage.[1][23]Sumerians would have household vessels made of clay, stone copper, and bronze. People would use braziers to heat their homes by burning animal dung.[19] People would light their houses by placing a wick made of reed or wool in sesame seed oil then lighting it.[8] Statues would usually be hidden inside houses in order to ward off evil spirits.[8] Statues were not the only religious furniture in Sumeria. Many clay plaques and figurines would depict everyday life and apotropaic gods and demons.[24] It is also worth noting that in Mesopotamian art gods would often be depicted sitting on mountains or heaps of produce. Some gods could be depicted as sitting on stools. These stools were likely representative for temples or the gods seat on Earth.[25]In Ancient Sumeria doors would be made out of wood or red ox-hide.[24] A variety of furniture dedicated to relaxing existed in Ancient Mesopotamia. Some ancient art depicts people lounging on sofas.[26] The legs of the sofas had iron panels that depicted women and lions.[8] In Mesopotamia bathrooms would have had bathtubs, stools, jars, mirrors, and large water pitchers occasionally with a pottery dipper. Rich Sumerians would have toilets and proper drainage systems.[27][28]

Archaeology[]

Because of the perishable materials common throughout Sumerian furniture, archaeological evidence for Mesopotamian furniture is limited. The few sources we have consists of artifacts the Assyrians gained from their conquests.[26] From the Assyrian records we learn that Mesopotamian furniture was similar to Egyptian furniture. Although, it was heavier and had more curves then Egyptian furniture.[6] Another source for Sumerian furniture was depictions from the city of Ur.[29]

Babylonia[]

There are little sources for Babylonian furniture. As the Babylonians did put any furniture in tombs, aside from a few drinking vessels and some jewelry, few examples of Babylonian furniture survives. This, combined with the lack of artistic depictions of Babylonian furniture, aside from a few seals and terracottas results in our main sources for Babylonian furniture being textual. One Babylonian text mentions large and small chests, as well as 60 chairs. Each chair being of a different usage and materials. The source mentions the footstool. Claiming that it is "for bathing, portable, for the worker, for the barber, for the road, for the seal cutter, for the metal-worker, for the potter." The text also mentions foot-rests and beds. Beds are described as "to sit on, to lie on, of reeds, with oxen-feet, with goat's hair, stuffed with wool, stuffed with goat hair, of Sumerian type', and 'of Akkadian type'" Babylonian wills often mention important pieces of furniture. These wills mention chests to store textiles, clothing, beds, chairs and stools.

The few artistic depictions we have of Babylonian furniture showcase a variety of chairs and miniature models of bed. These chairs would often have their legs carved in the shape of claws, paws, or oxen-feet. Chairs from the Old and Middle Babylonian period chairs with curved backs are depicted in reliefs from the late third millennium BCE Some plaques from the reign of Gudea showcase chairs with sloped backs.[3] The beds would have been made of clay and had rectangular bed frames. It is common for these artistic depictions of beds to showcase a couple in the act of sexual intercourse.

Babylonian tables would be covered or inlaid with ivory. Depictions from the Neo-Babylonian Period display tables and chairs being used together during eating scenes. These tables also became more elaborate during this period.[3] Some household items include vessels for oil, wine, beer, and honey. Other household items include ladders, step bowls, bowls, mortars, pestles, reed-mats, cushions, tables, chairs, grindstones,. ovens, and furnace.[30] Reeds and palm branches were common materials used to make cheap everyday products such as mats, screens, boxes, containers, baskets, and colanders. Clay, was a much more common material. It was used to make plates, jars, jugs, storage, and cooking tools were made from clay. Metal, especially copper, was used to make cooking pots, mortars, and iron implements in mills.

The Babylonians were highly specialized in carpentry and "cabinet-making." Because of this the Babylonians would export furniture to the Assyrians and other civilizations. These pieces would made from wooden frames and covered in gold and inlaid with silver, precious stones, and ivory. The most elaborate pieces were found in temples.[31]

Assyria[]

In Ancient Assyria plaques would be used as furniture. The Ancient Assyrians had carved ivory pieces. They were used to make fan handles, boxes, and furniture inlays. The furniture would commonly depict flowers.[32] There was a wide variety of Assyrian chairs. Some chairs had backs and arms, some resembled a footstool. Sometimes Assyrian chairs would be placed so high a footstool was required to sit on them. Chairs and footstool would be furnished with cushions covered in tapestries. Wealthier Assyrians would also furnish their couches and bed frames with tapestries. Poorer Assyrians would have a single mattress instead of a bed. Assyrian tables had four legs, often these legs would be inlaid with ivory. Other metals could be inlaid into chairs and sofas. Households would also have bronze tripods for the purpose of holding vases of wine and water. Some vases were made of terracota, these vases could also be glazed with a blue vitrified substance resembling vases used by the Egyptians.[33] The tripods used to hold these vases had feet shaped to resemble oxen or clinched hands.[34]

Egypt[]

The basic forms of Egyptian furniture were defined in the Old Kingdom of Egypt. Later, during the 18th dynasty, there were significant developments in Egyptian furniture. However this could be a misconception caused by significantly more surviving pieces of furniture being from the 18th dynasty. It is possible that furniture developments in Egypt happened far before the 18th dynasty, and they would gradually develop over time.[35] Most Egyptian furniture was wooden, with rare examples of stone furniture. The stone furniture usually had portraits of gods on them.[36] In Ancient Egypt chairs were used by both the poor and the rich. However, thrones were exclusively used by the wealthy. According to F. Fetten (1985), Egyptian chairs were likely seen as status symbols.[35] Most couches and chairs in Ancient Egypt were constructed to appear as animals. There are depictions of a low-back ox-legged chair. Additionally, there is a portrait of Amenhotep III sitting in a low-back lion legged chair. Some furniture depicts events and people.

One notable chair is the Anderson chair. On the back of the Anderson chair, there is an ornament that was made of alternating light and dark wood. There are also circular inlays on the back of the chair and bones on the top rail of the chair. The legs of the chair are carved to appear like a lion's legs. While the feet of the Anderson chair are carved on horizontally lined spools. The chair was shaped to conform to the lumbar area in the back. Wide tenons that are fastened with pegs and mortised joints are used on the chair.

Other Egyptian chairs were mortised into vertical side rails. The rails, alongside curved braces pegged into the chair, hold up the back of the Egyptian chair. The rails are also mortised into each other. Some rails have 15 holes; others have 13.[37]

Living areas in Ancient Egypt would also have stands, stools, couches, and beds. Ceremonial stools would be blocks of stone or wood. If the stool was made out of wood it would have a flint seat.[6] Tables were rare in ancient Egypt. The tables that did exist were round.[36] Tables usually had four legs, although some had three legs or one leg. They were used for games and dining. The game Mehen would be played on a one legend table carved or inlaid into the shape of a snake. The Egyptians also had offering tables made of stone which would be placed in home shrines or tombs.

Footstools were made of wood. The Royal Footstool had enemies of Egypt painted on the footstool, so that way the pharaoh could symbolically crush them.[6][38]

Ancient beds found in the tombs of Tutankhamen and Hetepheres tended to resemble that of an animal, usually a bull. The beds sloped up towards the head. To prevent the sleeper from falling off the bed, there was a wooden footboard. Wood or ivory headrests were used instead of pillows. To upholster the beds, leather and fabrics were used to support the mattress; Egyptians would weave leather strips into the open holes of the bed frame. Royal beds would often be gilded and richly decorated. Beds were constructed out of wood and had a simple framework that was supported by four legs. A plaited flax cord was lashed to the side of the framework. The flax cords were used in weaving together opposite sides of the framework to form an elastic surface for the user.[6]

Dilmun[]

There is no surviving furniture from Dilmun. The only records of furniture in Dilmun are seals found mainly in Bahrain and Failaka.[39] On these seals, furniture is depicted from a side view. This forced historians to rely on the dimensions of furniture of other civilizations so they could recreate what the furniture of Dilmun looked like.[40]

Chairs and thrones would have been built out of Shorea wood. Dowels would have been used for mortise and tenon joints. Sharp chisels would carve hardwood into furniture. Turpentine was used to thin animal fat, wax, and honey to finish the wood. It is possible that glue could was used in the construction of furniture. Posts would penetrate the seat of the chair. Chairs had backs fixed to the lower frame of the seat. At the top of the back support of some chairs, there was a sphere with horns imitating a goat's or bull's head. In some seals, chairs are depicted with seats shaped like boxes.

The chairs would have been 90 cm high, the seat and the back support would have been 45 cm high or 17 inches high. The diameter of the back is 8 cm or 3 inches. The width of the seat is 70 cm (27 in), the depth of the seat is 50 cm (19 in). The legs were 5 cm by 5 cm (1 in by 1 in) or 10 cm by 5 cm (3 in by 1 in).

The seals depict thrones with stools in front of them. The people who would have used these thrones and were kings, important officials, or wealthy people. One seal depicts a throne with vertical back support and front legs. Another seal depicts a similar throne but with a rectangular frame base. Stools in Dilmun are well built and are similar to thrones. However, they have no back support. Stools would have been well decorated if they were used by gods, kings, officials, and rich people.

Very few tables have been depicted in seals from Dilmun. All of these tables are ceremonial. Dilmunite tables had a concave or crescent top sitting on a column that divides into three curved legs with bull's hooves. Such tables may have been used for trade.

Rectangular Hatched altars would be used for sacrificing items and animals to the Dilmunite gods. The tabletop of the altar is concave. Spikes would stick out of a column. The legs of the altar end in animal hooves. The column and legs may be one piece, with the concave top joining the piece. Some altars looked like double boxes.[40]

Although very rarely a complete vase, archaeology has resulted in pottery from the Dilmunite city of Qal'at al Bahrain being unearthed. There were two styles of pottery, "Barbar" and "Eastern." Sanctuaries would be filled with small figurines. Most of these figurines were of a bearded horseman holding a mount without reigns. Other figurines depicted hybrids between animals and people.[41] Inside ancient Dilmunite houses storage jars, painted pots, fine chisels, and copper have been found.[42]

Decorations for the furniture would have been borrowed from other civilizations.

Greece[]

Ancient Greek furniture was typically constructed out of wood, though it might also be made of stone or metal, such as bronze, iron, gold, and silver. Little wood survives from ancient Greece, though varieties mentioned in texts concerning Greece and Rome include maple, oak, beech, yew, and willow.[43] Pieces were assembled using mortise-and-tenon joinery, held together with lashings, pegs, metal nails, and glue. Wood was shaped by carving, steam treatment, the lathe, and furniture is known to have been decorated with ivory, tortoise shell, glass, gold, or other precious materials.[44] Similarly, furniture could be veneered with expensive types of wood to make the object appear more costly,[45] though classical furniture was often pared down in comparison to objects attested in the East, or those from earlier periods in Greece.[35]

Extensive research was done on the forms of Greek furniture by Gisela Richter, who utilized a typological approach based primarily on illustrated examples depicted in Greek art, and it is from Richter's account that the main types can be delineated.[46]

Seating[]

The modern word “throne” is derived from the ancient Greek thronos (Greek singular: θρόνος), which was a seat designated for deities or individuals of high status or honor.[47] The colossal chryselephantine statue of Zeus at Olympia, constructed by Phidias and lost in antiquity, featured the god Zeus seated on an elaborate throne, which was decorated with gold, precious stones, ebony, and ivory, according to Pausanias.[48] Less extravagant though more influential in later periods is the klismos (Greek singular: κλισμός), an elegant Greek chair with a curved backrest and legs whose form was copied by the Romans and is now part of the vocabulary of furniture design. A fine example is shown on the grave stele of Hegeso, dating to the late fifth century BCE.[49] As with earlier furniture from the east, the klismos and thronos could be accompanied by footstools.[50] There are three types of footstools outlined by Richter – those with plain straight legs, those with curved legs, and those shaped like boxes that would have sat directly on the ground.[51]

The most common form of Greek seat was the backless stool. These were known as diphroi (Greek singular: δίφρος) and they were easily portable.[52] The Parthenon frieze displays numerous examples, upon which the gods are seated.[53] Several fragments of a stool were discovered in the forth-century BCE. tomb in Thessaloniki, including two of the legs and four transverse stretchers. Once made of wood and covered in silver foil, all that remains of this piece are the parts made of precious metal.[54][55]

The folding stool, known as the diphros okladias (Greek singular: δίφρος ὀκλαδίας), was practical and portable. The Greek folding stool survives in numerous depictions, indicating its popularity in the Archaic and Classical periods; the type may have been derived from earlier Minoan and Mycenaean examples, which in turn were likely based on Egyptian models.[56] Greek folding stools might have plain straight legs or curved legs that typically ended in animal feet.[57]

Klinai[]

A couch or kline (Greek: κλίνη) was a form used in Greece as early as the late seventh century B.C.E.[58] The kline was rectangular and supported on four legs, two of which could be longer than the other, providing support for an armrest or headboard. Three types are distinguished by Richter – those with animal legs, those with “turned” legs, and those with “rectangular” legs, although this terminology is somewhat problematic.[59] The fabric would have been draped over the woven platform of the couch, and cushions would have been placed against the arm or headrest, making the Greek couch an item well suited for a symposium gathering. The foot of a bronze bed discovered in situ in the House of the Seals at Delos indicate how the “turned” legs of a kline might have appeared.[60] Numerous images of klinai are displayed on vases, topped by layers of intricately woven fabrics and pillows. These furnishings would have been made of leather, wool, or linen, though silk could also have been used. Stuffing for pillows, cushions, and beds could have been made of wool, feathers, leaves, or hay.[61]

Tables[]

In general, Greek tables (Greek singular: τράπεζα, τρἰπους, τετράπους, φάτνη, ὲλεóς) were low and often appear in depictions alongside klinai and could perhaps fit underneath.[62] The most common type of Greek table had a rectangular top supported on three legs, though numerous configurations exist. Tables could have circular tops, and four legs or even one central leg instead of three. Tables in ancient Greece were used mostly for dining purposes – in depictions of banquets, it appears as though each participant would have utilized a single table, rather than a collective use of a larger piece. On such occasions, tables would have been moved according to one's needs.[63]

Tables also would have figured prominently in religious contexts, as indicated in vase paintings. One example by the Chicago Painter from The Art Institute of Chicago, dating to around 450 B.C.E., shows an image of three women performing a Dionysian ritual, in which a table functions as an appropriate place to rest a kantharos – a wine vessel associated with Dionysus.[64] Other images indicate that tables could range in style from the highly ornate to the relatively unadorned.

Rome[]

To a large extent, the types and styles of ancient Roman furniture followed those of their Classical and Hellenistic Greek predecessors. Because of this, it is difficult to differentiate Roman forms from earlier Hellenistic ones in many cases. Gisela Richter's typological approach is useful in tracing developments of Greek furniture into Roman expressions.[65] Knowledge of Roman furniture is derived mainly from depictions in frescoes and representations in sculpture, along with actual pieces of furniture, fragments, and fittings, several of which were preserved by the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79. The most well-known archaeological sites with preserved images and fragments from the eruption are Pompeii and Herculaneum in Italy. There are fine examples of reconstructed Roman furniture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City as well as the Capitoline Museum in Rome.[66]

Chairs[]

The sella, or stool or chair, was the most common type of seating in the Roman period, probably because of its easy portability. The sella in its simplest form was inexpensive to make. Both slaves and emperors used it, although those of the poor were plain, while the wealthy had access to precious woods, ornamented with inlay, metal fittings, ivory, and silver and gold leaf. Bronze sellae from Herculaneum were squares and had straight legs, decorative stretchers, and a dished seat.[67] The sella curulis, or folding stool, was an important indicator of power in the Roman period.[68] There were sellae resembling both stools and chairs that folded in a scissor fashion to facilitate transport.[69]

The Roman cathedra was a chair with a back, although there is disagreement as to the exact meaning of the Latin term. Richter defines the cathedra as a later version of the Greek klismos, which she says was never as popular as its Greek predecessor.[70] A. T. Croom, however, considers the cathedra to be a high-backed wickerwork chair that was typically associated with women. They have also been seen being used as early school teachers, pupils would sit around him in this chair while he taught. It showed who held the seat of power in the classroom.[71] As with Greek furniture, the names of various Roman types as found in texts cannot always be associated with known furniture forms with certainty.

The Latin solium is considered to be equivalent to the Greek term thronos and thus is often translated as “throne.”[72] These were like modern chairs, with backs and armrests. Three types of solia based on Greek prototypes are distinguished by Richter: thrones with “turned” and “rectangular” legs and grandiose thrones with solid sides, of which several examples remain in stone.[73] Also, a type with a high back and arms, resting upon a cylindrical or conical base, is said to derive from Etruscan prototypes.[74]

Couches[]

Few actual Roman couches survive, although sometimes the bronze fittings do, which help with the reconstruction of the original forms. While in wealthy households beds were used for sleeping in the bedrooms (lectus cubicularis), and couches for banqueting while reclining were used in the dining rooms (lectus tricliniaris), the less well off might use the same piece of furniture for both functions.[75] The two types might be used interchangeably even in richer households, and it is not always easy to differentiate between sleeping and dining furniture. The most common type of Roman bed took the form of a three-sided, open rectangular box, with the fourth (long) side of the bed open for access. While some beds were framed with boards, others had slanted structures at the ends, called fulcra, to better accommodate pillows. The fulcra of elaborate dining couches often had sumptuous decorative attachments featuring ivory, bronze, copper, gold, or silver ornamentation.[76]

The bench, or subsellium, was an elongated stool for two or more users. Benches were considered to be “seats of the humble,” and were used in peasant houses, farms, and bathhouses. However, they were also found in lecture halls, in the vestibules of temples, and served as the seats of senators and judges. Roman benches, like their Greek precedents, were practical for the seating of large groups of people and were common in theaters, amphitheaters, odeons and auctions.[77] The scamnum, related to the subsellium but smaller, was used as both a bench and a footstool.[78]

Tables[]

Types of Roman tables include the abacus and the mensa, which are distinguished from one another in Latin texts. The term abacus might be used for utilitarian tables, such as those for making shoes or kneading dough, as well as high-status tables, such as sideboards for the display of silverware.[79] A low, three-legged table, thought to represent the mensa delphica, was often depicted next to reclining banqueters in Roman paintings. This table has a round tabletop supported by three legs configured like those of a tripod.[80] Several wooden tables of this type were recovered from Herculaneum.

Surviving examples[]

The most important source for wooden furniture of the Roman period is the collection of carbonized furniture from Herculaneum. While the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 C.E. was tremendously destructive to the region, the pyroclastic surges that engulfed the town of Herculaneum ultimately preserved the wooden furniture, shelves, doors, and shutters in carbonized form.[81] Their preservation, however, is imperiled, as some of the pieces remain in situ in their houses and shops, encased in unprotected glass or entirely open and accessible. Upon excavation, much of the furniture was conserved with paraffin wax mixed with carbon powder, which coats the wood and obscures important details such as decorations and joinery. It is now impossible to remove the wax coating without further damaging the furniture. Several wooden pieces were found with bone and metal fittings.[82]

Wooden shelving and racks are found in shops and kitchens in the Vesuvian sites, and one house has elaborate wooden room dividers.

India[]

Bamboo, alongside Shisham, Mango, and Teak wood were common furniture materials in Ancient India.[83] The bamboo's colors ranged from yellow to black.[84] The lower classes of Ancient India had beds made of a mat extended across a small frame. Houses of the poor would also have basins, stone jar-stands, querns, palettes, flat dishes, a brass drinking vessel with a spout, a lamp, jars, mortar, pots, knives, saws, axes, and ivory needles and awls.[85] Indians also had access to wooden chairs, bed stands, and stools. As well as reed mats, bamboo thrones, and copper lamps.[86]

Japan[]

In the earliest parts of Japanese history, during the Kōbun Period, people lived in pit dwellings. These pit dwellings had straw mats called mushiro, pitch pine lamps, oil lamps, baskets, and lacquerware. The beds in these houses were made from dirt and there were open hearths.[87]

Eventually, houses started to be built out of timber with its bark unshaven. To help build the house posts were planted in holes in the ground and gables were placed in the grass. These houses would have antechambers made for women. The antechamber was separated from the rest of the world by doors made of curtains and window blinds made of grass called Sudare. Beds would be made by stacking mushiro mats and then spreading the mats with a fusuma quilt. Above the bed was a canopy called a shōjin made of a wood-lath grid covered in mushiro mats. The canopy would catch dust.

Later in Japanese history screens would become common furniture. The byobu is a multi-paneled screen covered in paintings. A screen covered by only one painting was called a tsuitate. Japanese households also had family shrines called butsudan. Other than reading stands, writing stands, headrests, Kimono racks, and armrests, there was no other furniture in Japan. This was because Japanese people would often sit on the floor rather than tables or chairs. This practice was given to the Japanese by the Chinese. Other Asian cultures borrowed furniture from the Chinese, such as Korea. Most furniture would not be decorated unless it was lacquered.[88]

Despite the fact that bamboo was common in the furniture of India and China, bamboo was not common in Japanese furniture.[84]

China[]

In the Ming dynasty, mainly in southern China, bamboo was used to make furniture that would be used outside. Furniture could also be made from dense hardwoods and softwoods. Hardwood was valued for its grain patterns and its beauty. Wealthy Chinese people would use lacquered wood, sometimes polychrome lacquered wood.[89] Most wooden furniture in Ancient China was lacquered. Joinery was also common in ancient Chinese and Indian furniture.[84] Mortise and tenon joints were very common in Chinese furniture.

Tables and desks were very low because oftentimes people would sit on the ground. An ancient bed found in Xinjiang is supported by six feet and is painted with a cloud pattern. People would often use beds as dining tables. Rich people would often decorate their beds with screens, curtains, and maybe jewelry to show off their wealth. Couches were smaller than beds and could usually only seat two people. Later, tall furniture would become popular in China.[90] Before this most furniture was below 50 cm or 19 inches.

One ancient Chinese chest located in an ancient tomb was painted with mystical patterns and mythical beings such as the god Fuxi. The story of Hou Yi and a diagram of constellations were also carved on the chest. In Ancient China there was a type of chair called a huchaung.[90] The huchaung was a consolable folding chair.

Israel[]

The Hebrews may have borrowed much of their furniture from other civilizations.[91] In Ancient Israel King Solomon supposedly had a bed made of cedar, silver, and gold. Most people would sleep on mats, but rich people had beds with pillows. The pillows would be made from goatskins filled with feathers or wool. Solomon's bed was made from ivory, with linen sheets, and scented with cinnamon and other spices.[92] Israelites had wardrobes made of ivory. They also had some furniture made of wood such as olive wood.[93][94]

Ivories were common in ancient Israeli furniture. The ivories would be used in furniture inlays, and they would be carved into round and lace-like plaques. They would also have patterns of colored paste with precious stones coated with gold or leaves. Alternatively, they could have the colored paste and stones painted. These ivories would have Phoenician letters inscribed on their backs. Ivories tended to be around beds, chairs, and stools. Ancient Israelites also had cosmetic spoons, cosmetic bottle stoppers, and round pyxides mirror handles.[95][96]

Most houses would only have a table and chairs. It is entirely possible that instead of a table there would just be a raised piece of earth. They would have cushions and mats and they would eat from a platter of food. Ordinary people would have stools or chairs with footrests and armrests. No chair had upholstery. Solomon had a throne laid with ivory carvings and plated in gold. The throne was six steps higher than the floor.

Mesoamerica[]

Maya[]

In one Mayan ceramic, a god is shown seated on a throne-like stool covered in cloth placed on a raised platform. In Chichen Itza, a carved stone called a chacmool was used to hold offerings in sacrificial ceremonies. The chacmool was painted with bright colors.[97] Instead of doors, Mayan homes may have had a cloth or a blanket hanging on the entryway. Bed frames were made from wood and covered in a woven straw mat. The bed frames were usually very low on the floor. Most likely, the only big furniture in a home would be wooden stools or benches. However, it is likely there would be baskets, small wooden chests, cotton bags, pottery, and stone tools. Mayans usually would hang bunches of chili peppers from the roofs of their houses. A hollowed-out chunk of wood called a bee pot was also common. Bees would be housed in the pot to make honey. The bees did not have a stinger.[98]

Aztecs[]

The Aztecs had little furniture. They sat and slept on mats made from reeds. Sometimes the Aztecs would sleep on dirt platforms. Wealthy people would have curtains and murals around their sleeping areas.[99] They kept their belongings in wooden blocks or reed chests.[100] Looms, pots, frying pans, and grinding stones for grinding corn, hunting, and fishing gear were common tools amongst the Aztecs.[101] The Tlatoani had chairs, dining tables, and ceremonial shrines.[102]

Incans[]

In Incan temples, the important areas were decorated with gold and polished reflective surfaces. The typical Incan house had adobe walls with hollow niches to store items. Incan houses also had animal skins and woven mats to decorate their floors. They also used brightly dyed woven materials for blankets and wall hangings.[97] Pucará de Tilcara has sites related to crafts production, processing, storage, and food consumption. Some areas were reused for burial. [103]

References[]

- ^ a b Somervill, Barbara A. (2009). Empires of Ancient Mesopotamia. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60413-157-4.

- ^ a b Gadotti, Alhena (2014-08-08). Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld and the Sumerian Gilgamesh Cycle. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 978-1-61451-545-6.

- ^ a b c Kubba, Sam (2011). The Iraqi Marshlands and the Marsh Arabs: The Ma'dan, Their Culture and the Environment. Trans Pacific Press. ISBN 978-0-86372-333-9.

- ^ McIntosh, Jane (2008). The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-907-2.

- ^ McIntosh, Jane (2008). The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-907-2.

- ^ a b c d e "Furniture - History". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-01-11.

- ^ a b c Foster, Benjamin R. (2015-12-14). The Age of Agade: Inventing Empire in Ancient Mesopotamia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-41552-7.

- ^ a b c d e Nemet-Nejat, Karen Rhea (1998). Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-29497-6.

- ^ Yildiz, Inar. Mesopotamian and Egyptian Furniture and Interior Decoration. p. 328.

- ^ a b Woolley, Leonard; Woolley, Sir Leonard (1965). The Sumerians. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-00292-8.

- ^ a b Fagan, Brian; Durrani, Nadia (2019-09-24). What We Did in Bed: A Horizontal History. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-24501-1.

- ^ Scholl, Elizabeth (2010-12-23). In Ancient Mesopotamia. Mitchell Lane Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-1-61228-019-6.

- ^ a b Kramer, Samuel Noah (2010-09-17). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-45232-6.

- ^ Forrest, Kent (1969-09-01). Sumer and Babylonia. Lorenz Educational Press. ISBN 978-1-55863-387-2.

- ^ Budge, E. A. Wallis (2005). Babylonian Life and History. Barnes & Noble Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7607-6549-4.

- ^ Woolley, Leonard; Woolley, Sir Leonard (1965). The Sumerians. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-00292-8.

- ^ Black, Jeremy A. (2006). The Literature of Ancient Sumer. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-929633-0.

- ^ Rykwert, Joseph (1998-02-06). The Dancing Column: On Order in Architecture. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-68101-8.

- ^ a b Kahn, Charles; Osborne, Ken (2005). World History: Societies of the Past. Portage & Main Press. ISBN 978-1-55379-045-7.

- ^ Cicero, Nuria (2016-12-15). A Visual History of Houses and Cities Around the World. The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4994-6573-0.

- ^ Charvát, Petr (2017-04-01). Signs from Silence. Charles University in Prague, Karolinum Press. ISBN 978-80-246-3130-1.

- ^ Veldhuis, Niek (2004). Religion, Literature, and Scholarship: The Sumerian Composition of Nanése and the Birds, with a Catalogue of Sumerian Bird Names. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-13950-3.

- ^ Crawford, Harriet (2013-08-29). The Sumerian World. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-21912-2.

- ^ a b Crawford, Harriet E. W.; Crawford, Harriet Elizabeth Walston; Crawford, Professor Harriet (1991-04-26). Sumer and the Sumerians. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-38850-4.

- ^ Lambert, Wilfred G. (2013-10-24). Babylonian Creation Myths. Penn State Press. ISBN 978-1-57506-861-9.

- ^ a b Nardo, Don (2009-03-17). Ancient Mesopotamia. Greenhaven Publishing LLC. ISBN 978-0-7377-4625-9.

- ^ Gates, Charles (2011-03-21). Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-136-82328-2.

- ^ Yildiz, Inar. Furniture Styles in History Part II: Ancient Furniture.

- ^ Boyce, Charles (2014-01-02). Dictionary of Furniture: Second Edition. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-62873-840-7.

- ^ Leick, Gwendolyn (2009-06-02). The Babylonian World. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-26128-4.

- ^ Leick, Gwendolyn (2003). The Babylonians: An Introduction. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-25314-7.

- ^ "What Is Ancient Assyrian Art? Discover the Visual Culture of This Powerful Empire". My Modern Met. 2020-12-27. Retrieved 2021-01-22.

- ^ Bonomi, Joseph (1869). Nineveh and its Palaces ... New edition, revised and augmented, etc. Bell & Daldy.

- ^ Thompson, R. Campbell; Classics, Delphi (2017-07-24). The Epic of Gilgamesh - Old Babylonian and Standard versions (Illustrated). Delphi Classics. ISBN 978-1-78656-215-9.

- ^ a b c Stephanus T. A. M. Mols, Wooden Furniture in Herculaneum: Form, Technique and Function, in vol. 2 of Circumvesuviana (Amsterdam: Gieben, 1999), 10. These relatively simple varieties of furniture may be connected to ancient Greek sumptuary laws. The effects of these laws on craftsmen are discussed by Alison Burford in Craftsmen in Greek and Roman Society (Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1972), 146.

- ^ a b Hunter, George Leland (1923). Decorative Furniture: A Picture Book of the Beautiful Forms of All Ages and All Periods ... Good Furniture Magazine ; Dean-Hicks Company.

- ^ Good Furniture & Decoration. National Trade Journals. 1921.

- ^ KILLEN, GEOFFREY. Ancient Egyptian Furniture Volume I: 4000 – 1300 BC. 2nd ed., vol. 1, Oxbow Books, 2017. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1m321gz. Accessed 11 Jan. 2021.

- ^ Werr, L. Al-Gailani (1986). "Gulf (Dilmun) Style Cylinder Seals". Seminar for Arabian Studies. 16: 199–201. JSTOR 41223247 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b Alexiou, Platon (2019). Approaching the Ancient Dilmum Furniture. United Arab Emirates: Ajman University. ISBN 978-9948-35-108-5.

- ^ Pierre Lombard. Qal’at al-Bahrain, Ancient Capital and Harbour of Dilmun. The Site Museum. Bahrain. Bahrain Authority for Culture and Antiquities, 2016, 978-99958-4-050-1. ffhal-01842044f

- ^ Crawford, Harriet (1995). "Dilmun, victim of world recession". Seminar for Arabian Studies. 26: 13–22. JSTOR 41223567 – via JSTOR.

- ^ G.M.A. Richter, The Furniture of the Greeks, Etruscans, and Romans (London: Phaidon, 1966), 122. First published in 1926 with an updated version in 1966.

- ^ Richter, 125.

- ^ Richter, 125-126.

- ^ See section on “Greek Furniture” in Richter, 13-84, in which the author describes Greek furniture and its typology.

- ^ Richter, 13.

- ^ Richter, 14; NH 5.11.2ff.

- ^ Linda Maria Gigante, “Funerary Art,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, Vol. 1, ed. Michael Gagarin and Elaine Fantham (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 246.

- ^ Richter, 49.

- ^ Richter, 50-51.

- ^ E. Guhl, and W. Koner, Everyday Life in Greek and Roman Times (New York: Crescent, 1989), 133.

- ^ Elizabeth Simpson, “Furniture,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, Vol. 1, ed. Michael Gagarin and Elaine Fantham (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 254.

- ^ Dimitra Andrianou, The Furniture and Furnishings of Ancient Greek Houses and Tombs (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009) 28-29, figure 6a.

- ^ Gargain, Michael (2010). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Ole Wanscher, Sella Curulis: The Folding Stool, an Ancient Symbol of Dignity (Copenhagen: Rosenkilde and Bagger, 1980), 83.

- ^ Richter, 43.

- ^ Simpson, 253.

- ^ Richter, 54; Richter defines “turned” (as in lathe-turned) legs on page 19 as being tripartite, with a middle “lozenge-shaped” portion capped by conical, “flaring” pieces at either end. This terminology is problematic in that it implies woodworking techniques, while the “turned” leg could have been executed in other materials, such as stone, metal, or ivory. Richter defines “rectangular” legs on page 23 as those that are “straight” though these can be curved and footed and often decorated with palettes and volutes.

- ^ Andrianou, 36.

- ^ Richter, 117.

- ^ Richter, 63.

- ^ Richter, 66.

- ^ Chicago Painter, stamnos, ca. 450 B.C.E. The Art Institute of Chicago, 1889.22.

- ^ Richter, 97-116.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. 11 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 363 to 365.

- ^ Lucia Pirzio Biroli Stefanelli, Il bronzo dei romani: arredo e suppellettile (Rome: L’Erma" di Bretschneider, 1991), 140-142.

- ^ Wanscher, 121.

- ^ Roger B. Ulrich, Roman Woodworking (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 221.

- ^ Richter, 101; Ulrich, 215.

- ^ A. T. Croom, Roman Furniture (Stroud, Gloucestershire, Great Britain: Tempus, 2007), 116.

- ^ Richter, 98; Ulrich, 215-216.

- ^ Richter, 98-101.

- ^ Richter, 10. According to Ulrich, Pliny uses the Greek term cathedra instead of solium for wicker armchairs, 215-218. Croom, however, refers to this chair as cathedra on p. 116.

- ^ Croom, 32.

- ^ Ulrich, 232-233.

- ^ Richter, 104; Croom, 110.

- ^ Ulrich, 219.

- ^ Ulrich, 223-224.

- ^ Ulrich, 225.

- ^ Mols, 1.

- ^ Mols, 19.

- ^ Litchfield, Frederick (1903). Illustrated History of Furniture. Truslove & hanson.

- ^ a b c Boyce, Charles (2014-01-02). Dictionary of Furniture: Second Edition. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-62873-840-7.

- ^ India (1851). India, Ancient and Modern; or, the History of Hindostan, civil and military, etc. Cradock & Company.

- ^ Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra (1977). Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-0436-4.

- ^ 和子·小泉 (1986). 和家具. Kodansha International. ISBN 978-0-87011-722-0.

- ^ Boyce, Charles (2014-01-02). Dictionary of Furniture: Second Edition. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-62873-840-7.

- ^ Handler, Sarah (2001-10-30). Austere Luminosity of Chinese Classical Furniture. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21484-2.

- ^ a b Zhang, Xiaoming (2011-03-03). Chinese Furniture. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-18646-9.

- ^ Pollen, John Hungerford (1886). Ancient and Modern Furniture and Woodwork. Committee of Council on Education.

- ^ Sherman, Josepha (2004-01-01). Your Travel Guide to Ancient Israel. Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 978-0-8225-3072-5.

- ^ Dever, William G. (2012-04-20). The Lives of Ordinary People in Ancient Israel: When Archaeology and the Bible Intersect. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-6701-8.

- ^ King, Philip J.; Stager, Lawrence E. (2001-01-01). Life in Biblical Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22148-5.

- ^ Ben-Tor, Amnon (1992-01-01). The Archaeology of Ancient Israel. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-05919-9.

- ^ Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2002-03-06). The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Sacred Texts. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-2338-6.

- ^ a b Pile, John F. (2005). A History of Interior Design. Laurence King Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85669-418-6.

- ^ Day, Nancy (2001-01-01). Your Travel Guide to the Ancient Mayan Civilization. Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 978-0-8225-3077-0.

- ^ Kenney, Karen Latchana (2015-01-01). Ancient Aztecs. ABDO. ISBN 978-1-62969-298-2.

- ^ DK (2011-08-15). DK Eyewitness Books: Aztec, Inca & Maya: Discover the World of the Aztecs, Incas, and Mayas—their Beliefs, Rituals, and Civilizations. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-7566-8952-0.

- ^ Marty, Lisa (2006-09-01). Ancient Aztecs. Lorenz Educational Press. ISBN 978-0-7877-0614-2.

- ^ Service, Social Studies School (2006). Aztec, Maya, Inca. Social Studies. ISBN 978-1-56004-254-9.

- ^ Tarrago, Myriam. "Reconstructing Inca Socioeconomic Organization through Biography Analyses of Residential Houses and Workshops of Pucara De Tilcara (Quebrada De Humahuaca, Argentine)". Journal of Archaeology and Anthropology. 5: 56 – via Academia.edu.

Sources[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ancient furniture. |

- Andrianou, Dimitra. The Furniture and Furnishings of Ancient Greek Houses and Tombs. New York: Cambridge UP, 2009.

- Baker, Hollis S. Furniture in the Ancient World: Origins & Evolution, 3100-475 B.C. New York: Macmillan, 1966.

- Blakemore, Robbie G. History of Interior Design & Furniture: from Ancient Egypt to Nineteenth-century Europe. Hoboken, NJ: J. Wiley & Sons, 2006.

- Boger, Louise Ade. Furniture Past & Present: A Complete Illustrated Guide to Furniture Styles from Ancient to Modern. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1966.

- Burford, Alison. Craftsmen in Greek and Roman Society. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1972.

- Gigante, Linda Maria. “Funerary Art,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome. Vol. 1. Edited by Michael Gagarin and Elaine Fantham. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Guhl, E., and W. Koner. Everyday Life in Greek and Roman Times. New York: Crescent, 1989.

- Mols, Stephanus T.A.M. Wooden Furniture in Herculaneum: Form, Technique and Function. Vol. 2 of Circumvesuviana. Amsterdam: Gieben, 1999.

- Nevett, Lisa C. Domestic Space in Classical Antiquity. New York: Cambridge UP, 2010.

- Pollen, John Hungerford. Ancient and Modern Furniture and Woodwork. London: Pub. for the Committee of Council on Education, by Chapman and Hall, 1875. South Kensington Museum of Art Handbooks, No. 3.

- Richter, G.M.A. The Furniture of the Greeks, Etruscans, and Romans. London: Phaidon, 1966.

- Robsjohn-Gibbings, Terence Harold, and Carlton W. Pullin. Furniture of Classical Greece. New York: Knopf, 1963.

- Simpson, Elizabeth. “Furniture,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome. Vol. 1. Edited by Michael Gagarin and Elaine Fantham. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Wanscher, Ole. Sella Curulis: The Folding Stool, an Ancient Symbol of Dignity. Copenhagen: Rosenkilde and Bagger, 1980.

- History of furniture

- Ancient Greek culture

- Ancient Roman furniture

- Ancient Greek art

- Ancient Roman art

- Sumerian art and architecture

- Ancient Egyptian architecture

- Ancient Roman culture

- Ancient Egyptian culture

- Ancient Indian culture

- Chinese art

- Japanese art

- Japanese culture

- Chinese culture