Angel

An angel is a supernatural being in various religions. The theological study of angels is known as angelology.

Abrahamic religions often depict them as benevolent celestial intermediaries between God (or Heaven) and humanity.[1][2] Other roles include protectors and guides for humans, and servants of God.[3] Abrahamic religions describe angelic hierarchies, which vary by sect and religion. Some angels have specific names (such as Gabriel or Michael) or titles (such as seraph or archangel). Those expelled from Heaven are called fallen angels, distinct from the heavenly host.

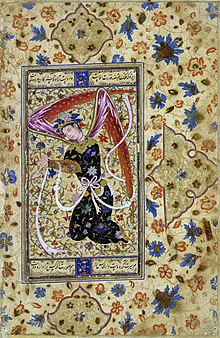

Angels in art are usually shaped like humans of extraordinary beauty.[4] They are often identified in Christian artwork with bird wings,[5] halos,[6] and divine light.

Etymology[]

The word angel arrives in modern English from Old English engel (with a hard g) and the Old French angele.[7] Both of these derive from Late Latin angelus, which in turn was borrowed from Late Greek ἄγγελος angelos (literally "messenger").[8] Τhe word's earliest form is Mycenaean a-ke-ro, attested in Linear B syllabic script.[9] According to the Dutch linguist R. S. P. Beekes, ángelos itself may be "an Oriental loan, like ἄγγαρος (ángaros, 'Persian mounted courier')."[10]

The rendering of "ángelos" is the Septuagint's default translation of the Biblical Hebrew term malʼākh, denoting simply "messenger" without connoting its nature. In the Latin Vulgate, this meaning becomes bifurcated: when malʼākh or ángelos is supposed to denote a human messenger, words like nuntius or legatus are applied. If the word refers to some supernatural being, the word angelus appears. Such differentiation has been taken over by later vernacular translations of the Bible, early Christian and Jewish exegetes and eventually modern scholars.[11]

Zoroastrianism[]

In Zoroastrianism there are different angel-like figures. For example, the Amesha Spentas, the six divine beings created by Ahura Mazdā ("Wise Lord", God) according to the Gathas of Zarathustra, function as "archangels" and are considered as such in Middle Persian Zoroastrian writings.[12]

Each person also has one guardian angel, called Fravashi. They patronize human beings and other creatures, and also manifest God's energy. The Amesha Spentas have often been regarded as angels, although there is no direct reference to them conveying messages,[13] but are rather emanations of Ahura Mazdā; they initially appeared in an abstract fashion and then later became personalized, associated with diverse aspects of the divine creation.[14]

Abrahamic religions[]

Judaism[]

Angels, Hebrew מלאך mal'ach "messenger", are understood in Judaism through interpretation of the Tanach and in a long tradition as supernatural beings who stand by God in heaven, but are strictly to be distinguished from God (YHWH) and are subordinate to him. Occasionally, they can show selected people God's will and instructions.[15] In the Jewish tradition they are also inferior to humans, since they have no will of their own and are only able to carry out one divine command.[16]

Pentateuch[]

The Torah uses the Hebrew terms מלאך אלהים (mal'āk̠ 'ĕlōhîm; "messenger of God"), מלאך יהוה (mal'āk̠ YHWH; "messenger of the Lord"), בני אלהים (bənē 'ĕlōhîm; "sons of God") and הקודשים (haqqôd̠əšîm; "the holy ones") to refer to beings traditionally interpreted as angels. Later texts use other terms, such as העליונים (hā'elyônîm; "the upper ones").

The term 'מלאך' ('mal'āk̠') is also used in other books of the Tanakh. Depending on the context, the Hebrew word may refer to a human messenger or to a supernatural messenger. A human messenger might be a prophet or priest, such as Malachi, "my messenger"; the Greek superscription in the Septuagint translation states the Book of Malachi was written "by the hand of his messenger" ἀγγέλου (angélu). Examples of a supernatural messenger[17] are the "Malak YHWH," who is either a messenger from God,[18] an aspect of God (such as the Logos),[19] or God himself as the messenger (the "theophanic angel.")[17][20]

Scholar Michael D. Coogan notes that it is only in the late books that the terms "come to mean the benevolent semi-divine beings familiar from later mythology and art."[21] Daniel is the first biblical figure to refer to individual angels by name,[22] mentioning Gabriel (God's primary messenger) in Daniel 9:21 and Michael (the holy fighter) in Daniel 10:13. These angels are part of Daniel's apocalyptic visions and are an important part of all apocalyptic literature.[21][23]

In Daniel 7, Daniel receives a dream-vision from God. [...] As Daniel watches, the Ancient of Days takes his seat on the throne of heaven and sits in judgement in the midst of the heavenly court [...] an [angel] like a son of man approaches the Ancient One in the clouds of heaven and is given everlasting kingship.[24]

Coogan explains the development of this concept of angels: "In the postexilic period, with the development of explicit monotheism, these divine beings—the 'sons of God' who were members of the Divine Council—were in effect demoted to what are now known as 'angels', understood as beings created by God, but immortal and thus superior to humans."[21] This conception of angels is best understood in contrast to demons and is often thought to be "influenced by the ancient Persian religious tradition of Zoroastrianism, which viewed the world as a battleground between forces of good and forces of evil, between light and darkness."[21] One of these is hāššāṭān, a figure depicted in (among other places) the Book of Job.

Rabbinic Judaism[]

According to rabbinical Judaism, the angels have no bodies, but are eternally living creatures created out of fire and occasionally appear in Midrashim as competition with humans. Heavenly beings, strictly following the laws of God, become jealous of God's affection for man. Humans by following the Torah, in prayer, by resisting evil instincts (yetzer hara) and by Teshuva, are preferred to already flawless angels. As a result, they are also inferior to humans in the Jewish tradition. In the Midrash, the plural of El used in Genesis in relation to the creation of human beings is explained by the presence of angels: God therefore consulted with the angels, but made the final decision alone. This story serves as an example, teaching that the powerful should also consult with the weak. God's own final decision highlights God's undisputable omnipotence.[25]

In post-Biblical Judaism, certain angels took on particular significance and developed unique personalities and roles. Although these archangels were believed to rank among the heavenly host, no systematic hierarchy ever developed. Metatron is considered one of the highest of the angels in Merkabah and Kabbalist mysticism and often serves as a scribe; he is briefly mentioned in the Talmud[26] and figures prominently in Merkabah mystical texts. Michael, who serves as a warrior[27] and advocate for Israel (Daniel 10:13), is looked upon particularly fondly.[28] Gabriel is mentioned in the Book of Daniel (Daniel 8:15–17) and briefly in the Talmud,[29] as well as in many Merkabah mystical texts. There is no evidence in Judaism for the worship of angels, but there is evidence for the invocation and sometimes even conjuration of angels.[22]

Philo of Alexandria identifies the angel with the Logos inasmuch as the angel is the immaterial voice of God. The angel is something different from God himself, but is conceived as God's instrument.[30]

Four classes of ministering angels minister and utter praise before the Holy One, blessed be He: the first camp (led by) Michael on His right, the second camp (led by) Gabriel on His left, the third camp (led by) Uriel before Him, and the fourth camp (led by) Raphael behind Him; and the Shekhinah of the Holy One, blessed be He, is in the centre. He is sitting on a throne high and exalted[31]

Later interpretations[]

According to Kabbalah, there are four worlds and our world is the last world: the world of action (Assiyah). Angels exist in the worlds above as a 'task' of God. They are an extension of God to produce effects in this world. After an angel has completed its task, it ceases to exist. The angel is in effect the task. This is derived from the book of Genesis when Abraham meets with three angels and Lot meets with two. The task of one of the angels was to inform Abraham of his coming child. The other two were to save Lot and to destroy Sodom and Gomorrah.[22]

Jewish philosopher Maimonides explained his view of angels in his Guide for the Perplexed II:4 and II

... This leads Aristotle in turn to the demonstrated fact that God, glory and majesty to Him, does not do things by direct contact. God burns things by means of fire; fire is moved by the motion of the sphere; the sphere is moved by means of a disembodied intellect, these intellects being the 'angels which are near to Him', through whose mediation the spheres move ... thus totally disembodied minds exist which emanate from God and are the intermediaries between God and all the bodies [objects] here in this world.

— Guide for the Perplexed II:4, Maimonides

Maimonides had a neo-Aristotelian interpretation of the Bible. Maimonides writes that to the wise man, one sees that what the Bible and Talmud refer to as "angels" are actually allusions to the various laws of nature; they are the principles by which the physical universe operates.

For all forces are angels! How blind, how perniciously blind are the naive?! If you told someone who purports to be a sage of Israel that the Deity sends an angel who enters a woman's womb and there forms an embryo, he would think this a miracle and accept it as a mark of the majesty and power of the Deity, despite the fact that he believes an angel to be a body of fire one third the size of the entire world. All this, he thinks, is possible for God. But if you tell him that God placed in the sperm the power of forming and demarcating these organs, and that this is the angel, or that all forms are produced by the Active Intellect; that here is the angel, the "vice-regent of the world" constantly mentioned by the sages, then he will recoil.– Guide for the Perplexed II:4

Hierarchy[]

Maimonides, in his Yad ha-Chazakah: Yesodei ha-Torah, counts ten ranks of angels in the Jewish angelic hierarchy, beginning from the highest:

| Rank | Angel | Notes |

| 1 | Chayot Ha Kodesh | See Ezekiel 1,10 |

| 2 | Ophanim | See Ezekiel 1,10 |

| 3 | Erelim | See Isaiah 33:7 |

| 4 | Hashmallim | See Ezekiel 1:4 |

| 5 | Seraphim | See Isaiah 6 |

| 6 | Malakim | Messengers, angels |

| 7 | Elohim | "Godly beings" |

| 8 | Bene Elohim | "Sons of Godly beings" |

| 9 | Cherubim | See Hagigah 13b |

| 10 | Ishim | "manlike beings", see Genesis 18:2, Daniel 10:5 |

Individuals[]

From the Jewish Encyclopedia, entry "Angelology".[22]

- Michael (archangel) (translation: who is like God?), kindness of God, and stands up for the children of mankind

- Gabriel (archangel) (translation: God is my strength), performs acts of justice and power

(Only these two angels are mentioned by name in the Hebrew Bible; the rest are from extra-biblical tradition.)

- Jophiel (translation: Beauty of God), expelled Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden holding a flaming sword and punishes those who transgress against God.

- Raphael (archangel) (translation: It is God who heals), God's healing force

- Uriel (archangel) (translation: God is my light), leads us to destiny

- Samael (archangel) (translation: Venom of God), angel of death—see also Malach HaMavet (translation: the angel of death)

- Sandalphon (archangel) (translation: bringing together), battles Samael and brings mankind together

Christianity[]

Christians inherited Jewish understandings of angels, which in turn may have been partly inherited from the Egyptians.[32] In the early stage, the Christian concept of an angel characterized the angel as a messenger of God. Later came identification of individual angelic messengers: Gabriel, Michael, Raphael, and Uriel.[33] Then, in the space of little more than two centuries (from the 3rd to the 5th) the image of angels took on definite characteristics both in theology and in art.[34] Ellen Muehlberger has argued that in late antiquity, angels were conceived of as one type of being among many, whose primary purpose was to guard and to guide Christians.[35]

Bible[]

Angels are represented throughout the Christian Bible as spiritual beings intermediate between God and men: "You have made him [man] a little less than the angels ..." (Psalms 8:4–5). Christians believe that angels are created beings, based on (Psalms 148:2–5; Colossians 1:16): "praise ye Him, all His angels: praise ye Him, all His hosts ... for He spoke and they were made. He commanded and they were created ...". Greek translations of the Hebrew Bible refer to intermediary beings, as angels, instead of daimon, thus giving raise to a distinction between demons and angels. In the Old Testament, both benevolent and fierce angels are mentioned, nevertheless never called a demon. The symmetry lies between angels sent by God, and intermediary spirits of foreign deities, not in good and evil deeds.[36]

In the New Testament, the existence of angels, just like that of demons, is taken for granted.[37] They can intervene and intercede on behalf of humans. Angels warn humans of impending danger (Matt 4:6), protect the righteous (Matt 4:6; Luke 4:10) and reveal divine information otherwise unavailable for human beings.(Matt 1:10; Luke 1:20). They dwell in the heavens (Matt 28:2; (John 1:51), act as God's warriors (Matt 26:53) and worship the Divine (Luke 2:13).[38] In the parable about Lazarus and the rich man, angels behave as psychopomps. The Resurrection of Jesus features angels, telling the woman that Jesus is no longer in the tomb, but has risen from the dead.[39]

Theology[]

According to St. Augustine, "'Angel' is the name of their office, not of their nature. If you seek the name of their nature, it is 'spirit'; if you seek the name of their office, it is 'angel': from what they are, 'spirit', from what they do, 'angel'."[40] Basilian Father Thomas Rosica says, "Angels are very important, because they provide people with an articulation of the conviction that God is intimately involved in human life."[41] Gregory of Nazianzus thought that angels were made as 'spirits' and 'flames of fire', following Hebrews 1, and that they can be identified with the 'thrones, dominions, rulers and authorities' of Colossians 1.[35] [2]

By the late 4th century, the Church Fathers agreed that there were different categories of angels, with appropriate missions and activities assigned to them. There was, however, some disagreement regarding the nature of angels. Some argued that angels had physical bodies,[42] while some maintained that they were entirely spiritual. Some theologians had proposed that angels were not divine but on the level of immaterial beings subordinate to the Trinity. The resolution of this Trinitarian dispute included the development of doctrine about angels.[43]

The Forty Gospel Homilies by Pope Gregory I noted angels and archangels.[44] The Fourth Lateran Council (1215) declared that the angels were created beings. The council's decree Firmiter credimus (issued against the Albigenses) declared both that angels were created and that men were created after them. The First Vatican Council (1869) repeated this declaration in Dei Filius, the "Dogmatic constitution on the Catholic faith".

Thomas Aquinas (13th century) relates angels to Aristotle's metaphysics in his Summa contra Gentiles,[45] Summa Theologica,[46] and in De substantiis separatis,[47] a treatise on angelology. Although angels have greater knowledge than men, they are not omniscient, as Matthew 24:36 points out.[48]

Interaction[]

Forget not to show love unto strangers: for thereby some have entertained angels unawares.—Hebrews 13:2

The New Testament includes many interactions and conversations between angels and humans. For instance, three separate cases of angelic interaction deal with the births of John the Baptist and Jesus Christ. In Luke 1:11, an angel appears to Zechariah to inform him that he will have a child despite his old age, thus proclaiming the birth of John the Baptist. In Luke 1:26 the Archangel Gabriel visits the Virgin Mary in the Annunciation to foretell the birth of Jesus Christ. Angels then proclaim the birth of Jesus in the Adoration of the shepherds in Luke 2:10.[49]

According to Matthew 4:11, after Jesus spent 40 days in the desert, "...the Devil left him and, behold, angels came and ministered to him." In Luke 22:43 an angel comforts Jesus Christ during the Agony in the Garden.[50] In Matthew 28:5 an angel speaks at the empty tomb, following the Resurrection of Jesus and the rolling back of the stone by angels.[49]

In 1851 Pope Pius IX approved the Chaplet of Saint Michael based on the 1751 reported private revelation from archangel Michael to the Carmelite nun Antonia d'Astonac.[51] In a biography of Saint Gemma Galgani written by Venerable Germanus Ruoppolo, Galgani stated that she had spoken with her guardian angel.

Pope John Paul II emphasized the role of angels in Catholic teachings in his 1986 address titled "Angels Participate In History Of Salvation", in which he suggested that modern mentality should come to see the importance of angels.[52]

According to the Vatican's Congregation for Divine Worship and Discipline of the Sacraments, "The practice of assigning names to the Holy Angels should be discouraged, except in the cases of Gabriel, Raphael and Michael whose names are contained in Holy Scripture."[53]

The New Church (Swedenborgianism)[]

The New Church denominations that arose from the writings of theologian Emanuel Swedenborg have distinct ideas about angels and the spiritual world in which they dwell. Adherents believe that all angels are in human form with a spiritual body, and are not just minds without form.[54] There are different orders of angels according to the three heavens,[55] and each angel dwells in one of innumerable societies of angels. Such a society of angels can appear as one angel as a whole.[56]

All angels originate from the human race, and there is not one angel in heaven who first did not live in a material body.[57] Moreover, all children who die not only enter heaven but eventually become angels.[58] The life of angels is that of usefulness, and their functions are so many that they cannot be enumerated. However each angel will enter a service according to the use that they had performed in their earthly life.[59] Names of angels, such as Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael, signify a particular angelic function rather than an individual being.[60]

While living in one's body an individual has conjunction with heaven through the angels,[61] and with each person, there are at least two evil spirits and two angels.[62] Temptation or pains of conscience originates from a conflict between evil spirits and angels.[63] Due to man's sinful nature it is dangerous to have open direct communication with angels[64] and they can only be seen when one's spiritual sight has been opened.[65] Thus from moment to moment angels attempt to lead each person to what is good tacitly using the person's own thoughts.[66]

Latter Day Saints[]

The Latter Day Saint movement views angels as the messengers of God. They are sent to mankind to deliver messages, minister to humanity, teach doctrines of salvation, call mankind to repentance, give priesthood keys, save individuals in perilous times, and guide humankind.[67]

Latter Day Saints believe that angels either are the spirits of humans who are deceased or who have yet to be born, or are humans who have been resurrected or translated and have physical bodies of flesh and bones,[68] and accordingly Joseph Smith taught that "there are no angels who minister to this earth but those that do belong or have belonged to it."[69] As such, Latter Day Saints also believe that Adam, the first man, was and is now the archangel Michael,[70][71][72] and that Gabriel lived on the earth as Noah.[68] Likewise the Angel Moroni first lived in a pre-Columbian American civilization as the 5th-century prophet-warrior named Moroni.

Smith described his first angelic encounter in the following manner:[73]

"While I was thus in the act of calling upon God, I discovered a light appearing in my room, which continued to increase until the room was lighter than at noonday, when immediately a personage appeared at my bedside, standing in the air, for his feet did not touch the floor.

He had on a loose robe of most exquisite whiteness. It was a whiteness beyond anything earthly I had ever seen; nor do I believe that any earthly thing could be made to appear so exceedingly white and brilliant ...

Not only was his robe exceedingly white, but his whole person was glorious beyond description, and his countenance truly like lightning. The room was exceedingly light, but not so very bright as immediately around his person. When I first looked upon him, I was afraid; but the fear soon left me."

Most angelic visitations in the early Latter Day Saint movement were witnessed by Smith and Oliver Cowdery, who both said (prior to the establishment of the church in 1830) they had been visited by the prophet Moroni, John the Baptist, and the apostles Peter, James, and John. Later, after the dedication of the Kirtland Temple, Smith and Cowdery said they had been visited by Jesus, and subsequently by Moses, Elias, and Elijah.[74]

Others who said they received a visit by an angel include the other two of the Three Witnesses: David Whitmer and Martin Harris. Many other Latter Day Saints, both in the early and modern church, have said they had seen angels, although Smith posited that, except in extenuating circumstances such as the restoration, mortals teach mortals, spirits teach spirits, and resurrected beings teach other resurrected beings.[75]

Islam[]

Belief in angels is fundamental to Islam. The Quranic word for angel (Arabic: ملاك malak) derives either from Malaka, meaning "he controlled", due to their power to govern different affairs assigned to them,[76] or from the root either from ʼ-l-k, l-ʼ-k or m-l-k with the broad meaning of a "messenger", just like its counterparts in Hebrew (malʾákh) and Greek (angelos). Unlike their Hebrew counterpart, the term is exclusively used for heavenly spirits of the divine world, but not for human messengers. The Quran refers to both angelic and human messengers as "rasul" instead.[77]

The Quran is the principal source for the Islamic concept of angels.[78] Some of them, such as Gabriel and Michael, are mentioned by name in the Quran, others are only referred to by their function. In hadith literature, angels are often assigned to only one specific phenomena.[79] Angels play a significant role in Mi'raj literature, where Muhammad encounters several angels during his journey through the heavens.[80] Further angels have often been featured in Islamic eschatology, Islamic theology and Islamic philosophy.[81] Duties assigned to angels include, for example, communicating revelations from God, glorifying God, recording every person's actions, and taking a person's soul at the time of death.

In Islam, just like in Judaism and Christianity, angels are often represented in anthropomorphic forms combined with supernatural images, such as wings, being of great size or wearing heavenly articles.[82] The Quran describes them as "messengers with wings—two, or three, or four (pairs): He [God] adds to Creation as He pleases..."[83] Common characteristics for angels are their missing needs for bodily desires, such as eating and drinking.[84] Their lack of affinity to material desires is also expressed by their creation from light: Angels of mercy are created from nur (cold light) in opposition to the angels of punishment created from nar (hot light).[85] Muslims do not generally share the perceptions of angelic pictorial depictions, such as those found in Western art.

Although believing in angels remain one of Six Articles of Faith in Islam, one can not find a dogmatic angelology in Islamic tradition. Despite this, scholars had discussed the role of angels from specific canonical events, such as the Mi'raj, and Quranic verses. Even if they are not in focus, they have been featured in folklore, philosophy debates and systematic theology. While in classical Islam, widespread notions were accepted as canonical, there is a tendecy in contemporary scholarship to reject much material about angels, like calling the Angel of Death by the name Azra'il.[86]

In Folk Islam, individual angels may be evoked in exorcism rites, whose names are engraved in talismans or amulets.[87]

Some modern scholars have emphasized a metaphorical reinterpretation of the concept of angels.[88]

Neoplatonism[]

Philo of Alexandria already identified the Neo-Platonic interpretation of daemons as angels. The daemons were thought to be intermediary between the supernatural and earthly realm, interpreted by Philo as the Greek term for angels.[89]

In the commentaries of Proclus (4th century) on the Timaeus of Plato, Proclus uses the terminology of "angelic" (aggelikos) and "angel" (aggelos) in relation to metaphysical beings. According to Aristotle, just as there is a Prime Mover,[90] so, too, must there be spiritual secondary movers.[91]

Ibn Sina, who drew upon the Neo-Platonistic emanation cosmology of Al-Farabi, developed an angelological hierarchy of Intellects, which are created by "the One". Therefore, the first creation by God was the supreme archangel followed by other archangels, who are identified with lower Intellects. From these Intellects again, emanated lower angels or "moving spheres", from which in turn, emanated other Intellects until it reaches the Intellect, which reigns over the souls. The tenth Intellect is responsible for bringing material forms into being and illuminating the minds.[92][93]

Sikhism[]

This section uncritically uses texts from within a religion or faith system without referring to secondary sources that critically analyze them. (November 2010) |

The poetry of the holy scripture of the Sikhs – the Sri Guru Granth Sahib – figuratively mentions a messenger or angel of death, sometimes as Yam (ਜਮ – "Yam") and sometimes as Azrael (ਅਜਰਾਈਲੁ – "Ajraeel"):

- ਜਮ ਜੰਦਾਰੁ ਨ ਲਗਈ ਇਉ ਭਉਜਲੁ ਤਰੈ ਤਰਾਸਿ

- The Messenger of Death will not touch you; in this way, you shall cross over the terrifying world-ocean, carrying others across with you.

- — Sri Guru Granth Sahib, Siree Raag, First Mehl, p. 22.[94]

- ਅਜਰਾਈਲੁ ਯਾਰੁ ਬੰਦੇ ਜਿਸੁ ਤੇਰਾ ਆਧਾਰੁ

- Azraa-eel, the Messenger of Death, is the friend of the human being who has Your support, Lord.

- — Sri Guru Granth Sahib, Tilang, Fifth Mehl, Third House, p. 724.[95]

In a similar vein, the Sri Guru Granth Sahib talks of a figurative Chitar (ਚਿਤ੍ਰ) and Gupat (ਗੁਪਤੁ):

- ਚਿਤ੍ਰ ਗੁਪਤੁ ਸਭ ਲਿਖਤੇ ਲੇਖਾ ॥

- ਭਗਤ ਜਨਾ ਕਉ ਦ੍ਰਿਸਟਿ ਨ ਪੇਖਾ

- Chitar and Gupat, the recording angels of the conscious and the unconscious, write the accounts of all mortal beings, / but they cannot even see the Lord's humble devotees.

- — Sri Guru Granth Sahib, Aasaa, Fifth Mehl, Panch-Pada, p. 393.[96]

However, Sikhism has never had a literal system of angels, preferring guidance without explicit appeal to supernatural orders or beings.

Esotericism[]

Hermetic Qabalah[]

According to the Kabbalah as described by the Golden Dawn there are ten archangels, each commanding one of the choir of angels and corresponding to one of the Sephirot. It is similar to the Jewish angelic hierarchy.

| Rank | Choir of Angels | Translation | Archangel | Sephirah |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hayot Ha Kodesh | Holy Living Ones | Metatron | Keter |

| 2 | Ophanim | Wheels | Raziel | Chokmah |

| 3 | Erelim | Brave ones[97] | Tzaphkiel | Binah |

| 4 | Hashmallim | Glowing ones, Amber ones[98] | Tzadkiel | Chesed |

| 5 | Seraphim | Burning Ones | Khamael | Gevurah |

| 6 | Malakim | Messengers, angels | Raphael | Tipheret |

| 7 | Elohim | Godly Beings | Uriel | Netzach |

| 8 | Bene Elohim | Sons of Elohim | Michael | Hod |

| 9 | Cherubim | [99] | Gabriel | Yesod |

| 10 | Ishim | Men (man-like beings, phonetically similar to "fires") | Sandalphon | Malkuth |

Theosophy[]

In the teachings of the Theosophical Society, Devas are regarded as living either in the atmospheres of the planets of the solar system (Planetary Angels) or inside the Sun (Solar Angels) and they help to guide the operation of the processes of nature such as the process of evolution and the growth of plants; their appearance is reputedly like colored flames about the size of a human. It is believed by Theosophists that devas can be observed when the third eye is activated. Some (but not most) devas originally incarnated as human beings.[100]

It is believed by Theosophists that nature spirits, elementals (gnomes, undines, sylphs, and salamanders), and fairies also can be observed when the third eye is activated.[101] It is maintained by Theosophists that these less evolutionarily developed beings have never been previously incarnated as humans; they are regarded as being on a separate line of spiritual evolution called the "deva evolution"; eventually, as their souls advance as they reincarnate, it is believed they will incarnate as devas.[102]

It is asserted by Theosophists that all of the above-mentioned beings possess etheric bodies that are composed of etheric matter, a type of matter finer and more pure that is composed of smaller particles than ordinary physical plane matter.[102]

Other[]

Suitably the Greek magical papyri, a set of texts forming into a completed grimoire that date somewhere between 100 BC and 400 AD, also list the names of the angels found in monotheistic religions. Except in this saga they appear as deities.[103]

Numerous references to angels present themselves in the Nag Hammadi Library, in which they both appear as malevolent servants of the Demiurge and innocent associates of the aeons.[104]

Brahma Kumaris[]

The Brahma Kumaris uses the term "angel" to refer to a perfect, or complete state of the human being, which they believe can be attained through a connection with God.[105][106] It is expanded as a state of being rather that an entity.[105]

New religious movements[]

Baháʼí Faith[]

In his Book of Certitude Baháʼu'lláh, founder of the Baháʼí Faith, describes angels as people who "have consumed, with the fire of the love of God, all human traits and limitations", and have "clothed themselves" with angelic attributes and have become "endowed with the attributes of the spiritual". ʻAbdu'l-Bahá describes angels as the "confirmations of God and His celestial powers" and as "blessed beings who have severed all ties with this nether world" and "been released from the chains of self", and "revealers of God's abounding grace". The Baháʼí writings also refer to the Concourse on High, an angelic host, and the Maid of Heaven of Baháʼu'lláh's vision.[107]

"I raised my hand another time, and bared one of Her breasts that had been hidden beneath Her gown. Then the firmament was illumined by the radiance of its light, contingent beings were made resplendent by its appearance and effulgence, and by its rays infinite numbers of suns dawned forth, as though they trekked through heavens that were without beginning or end. I became bewildered at the pen of God's handiwork, and at what it had inscribed upon Her temple. It was as though She had appeared with a body of light in the forms of the spirit, as though She moved upon the earth of essence in the substance of manifestation. I noticed that the houris had poked their heads out of their rooms and were suspended in the air above Her. They grew perplexed at Her appearance and Her beauty, and were entranced by the raptures of Her song. Praise be to Her creator, fashioner, and maker--to the one Who made Her manifest.

Then she nearly swooned within herself, and with all her being she sought to inhale My fragrance. She opened Her lips, and the rays of light dawned forth from Her teeth, as though the pearls of the cause had appeared from Her treasures and Her shells.

She asked, "Who art Thou?"

I said, "A servant of God and the son of his maidservant.""

— Tablet of the Maiden[108], Baháʼu'lláh

Satanism[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (November 2018) |

The Satanic Temple heavily promotes what it calls "literary Satanism", the idea of Satan and fallen angels as literary figures and metaphors. In particular, the novel Revolt of the Angels by Anatole France is seen as an example of this tradition. In it, a guardian angel by the name Arcade organizes a revolt against Heaven after learning about science.

In art[]

According to mainstream Christian theology, angels are wholly spiritual beings and therefore do not eat, excrete or have sex, and have no gender. Although their different roles, such as warriors for some archangels, may suggest a human gender, Christian artists were careful not to given them specific gender attributes, at least until the 19th century, when some acquire breasts for example.[109]

In an address during a General Audience of 6 August 1986, entitled "Angels participate in the history of salvation", Pope John Paul II explained that "[T]he angels have no 'body' (even if, in particular circumstances, they reveal themselves under visible forms because of their mission for the good of people)."[52] Christian art perhaps reflects the descriptions in Revelation 4:6–8 of the Four Living Creatures (Greek: τὰ τέσσαρα ζῷα) and the descriptions in the Hebrew Bible of cherubim and seraphim (the chayot in Ezekiel's Merkabah vision and the Seraphim of Isaiah). However, while cherubim and seraphim have wings in the Bible, no angel is mentioned as having wings.[110] The earliest known Christian image of an angel—in the Cubicolo dell'Annunziazione in the Catacomb of Priscilla (mid-3rd century)—is without wings. In that same period, representations of angels on sarcophagi, lamps and reliquaries also show them without wings,[111] as for example the angel in the Sacrifice of Isaac scene in the Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus (although the side view of the Sarcophagus shows winged angelic figures).

The earliest known representation of angels with wings is on the "Prince's Sarcophagus", attributed to the time of Theodosius I (379–395), discovered at Sarigüzel, near Istanbul, in the 1930s.[112] From that period on, Christian art has represented angels mostly with wings, as in the cycle of mosaics in the Basilica of Saint Mary Major (432–440).[113] Four- and six-winged angels, drawn from the higher grades of angels (especially cherubim and seraphim) and often showing only their faces and wings, are derived from Persian art and are usually shown only in heavenly contexts, as opposed to performing tasks on earth. They often appear in the pendentives of church domes or semi-domes. Prior to the Judeo-Christian tradition, in the Greek world the goddess Nike and the gods Eros and Thanatos were also depicted in human-like form with wings.

Saint John Chrysostom explained the significance of angels' wings:

They manifest a nature's sublimity. That is why Gabriel is represented with wings. Not that angels have wings, but that you may know that they leave the heights and the most elevated dwelling to approach human nature. Accordingly, the wings attributed to these powers have no other meaning than to indicate the sublimity of their nature.[114]

Angels are typically depicted in Mormon art as having no wings based on a quote from Joseph Smith ("An angel of God never has wings").[115]

In terms of their clothing, angels, especially the Archangel Michael, were depicted as military-style agents of God and came to be shown wearing Late Antique military uniform. This uniform could be the normal military dress, with a tunic to about the knees, an armour breastplate and pteruges, but was often the specific dress of the bodyguard of the Byzantine Emperor, with a long tunic and the loros, the long gold and jewelled pallium restricted to the Imperial family and their closest guards.

The basic military dress was shown in Western art into the Baroque period and beyond (see Reni picture above), and up to the present day in Eastern Orthodox icons. Other angels came to be conventionally depicted in long robes, and in the later Middle Ages they often wear the vestments of a deacon, a cope over a dalmatic. This costume was used especially for Gabriel in Annunciation scenes—for example the Annunciation in Washington by Jan van Eyck.

Some types of angels are described as possessing more unusual or frightening attributes, such as the fiery bodies of the Seraphim, and the wheel-like structures of the Ophanim.

French Gothic angel from an altar, circa 1275–1300, oak with traces of paint, 73.7 × 19.4 × 19 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Italian Gothic adorning angel, circa 1395–1396, lunense marble from Carrara (Italy), overall: 118.7 x 28.6 x 32.4 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Italian Gothic angel of the annunciation, circa 1430–1440, Istrian limestone, gesso and gilt, 95.3 x 37.5 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Southern German Baroque angel, by Ignaz Günther, circa 1760–1770, lindenwood with traces of gesso, 26.7 x 18.4 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Angels holding a red textile and a Baroque cartouche, in the Charlottenburg Palace (Berlin)

Arquebusier Angels, Colonial Bolivia, were part of the Cusco School

The extraordinary-looking Cherubim (immediately to the right of Ezekiel) and Ophanim (the nested-wheels) appear in the chariot vision of Ezekiel

Corinthian capital with an angel who wolds a festoon with his wings, in Stiftskirche Mariae Himmelfahrt in Schlägl (Austria)

An angel in the former coat of arms of Tenala

See also[]

- Angel (Buffy the Vampire Slayer)

- Angelic chant

- Apsara

- Chalkydri

- Classification of demons

- Dakini

- Elioud

- Eudaemon (mythology)

- Exorcism

- Gandharva

- Genius (mythology)

- Holy Spirit

- Hierarchy of angels

- List of films about angels

- Neon Genesis Evangelion

- Substance theory

- Watcher (angel)

- Yaksha

- Angel Beats!

References[]

- ^ The Free Dictionary: "angel", retrieved 1 September 2012

- ^ ""Angels in Christianity." Religion Facts. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 Dec. 2014".

- ^ Augustine of Hippo's Enarrationes in Psalmos, 103, I, 15, augustinus.it (in Latin)

- ^ "ANGELOLOGY - JewishEncyclopedia.com". jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ Proverbio(2007), pp. 90–95; compare review in La Civiltà Cattolica, 3795–3796 (2–16 August 2008), pp. 327–328.

- ^ Didron, Vol 2, pp.68–71.

- ^ "angel – Definition of angel in English by Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries – English.

- ^ Strong, James. "Strong's Greek". Biblehub.com. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

Transliteration: aggelos Phonetic Spelling: (ang'-el-os)

- ^ palaeolexicon.com, a-ke-ro, Palaeolexicon.

- ^ Beekes, R. S. P., Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. 9.

- ^ Kosior, Wojciech. "The Angel in the Hebrew Bible from the Statistic and Hermeneutic Perspectives. Some Remarks on the Interpolation Theory". "The Polish Journal of Biblical Research", Vol. 12, No. 1 (23), Pp. 55–70. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ Jenny Rose, Zoroastrianism: A Guide for the Perplexed, 2011, p. 34.

- ^ Lewis, James R., Oliver, Evelyn Dorothy, Sisung Kelle S. (Editor) (1996), Angels A to Z, Entry: Zoroastrianism, pp. 425–427, Visible Ink Press, ISBN 0-7876-0652-9

- ^ Darmesteter, James (1880)(translator), The Zend Avesta, Part I: Sacred Books of the East, Vol. 4, pp. lx–lxxii, Oxford University Press, 1880, at sacred-texts.com

- ^ Hermann Röttger: Mal'ak jhwh, Bote von Gott. Die Vorstellung von Gottesboten im hebräischen Alten Testament. Peter Lang Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1978, ISBN 3-261-02633-2 (zugl. Dissertation, Universität Regensburg 1977). Johann Michl: Engel (jüd.). In: RAC, Band 5. Hiersemann Verlag, Stuttgart 1962, p. 60–97. (German)

- ^ Joseph Hertz: Kommentar zum Pentateuch, hier zu Gen 19,17 EU. Morascha Verlag Zürich, 1984. Band I, p. 164. (German)

- ^ Jump up to: a b ""מַלְאָךְ," Francis Brown, S.R. Driver, and Charles A. Briggs, eds.: A Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament, p. 521". Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Pope, Hugh. "Angels." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. accessed 20 October 2010

- ^ Frederick Copleston, A History of Philosophy, Volume 1, Continuum, 2003, p. 460.

- ^ Baker, Louis Goldberg. Evangelical Dictionary of Biblical Theology: Angel of the Lord "The functions of the angel of the Lord in the Old Testament prefigure the reconciling ministry of Jesus. In the New Testament, there is no mention of the angel of the Lord; the Messiah himself is this person."

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Coogan, Michael D. (2009). A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Angelology". The Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Dunn, James D. G. (15 July 2010). Did the First Christians Worship Jesus?: The New Testament Evidence. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-61164-070-0.

God sends an angel to communicate with prophets, and an interpreter angel appears regularly in apocalyptic visions and as companion in heavenly journeys. One of the most fascinating features of several ancient stories is the appearance of what can be called theophanic angels; that is, angels who not only bring a message from God, but who represent God in personal terms, or who even may be said to embody God.

- ^ Chilton, Bruce D. (2002). "(The) Son of (The) Man, and Jesus". In Craig A. Evans (ed.). Authenticating the Words of Jesus. BRILL. p. 276. ISBN 0-391-04163-0.

As described in the book of Daniel, “one like a son of man" is clearly identified as the messianic and angelic redeemer of Israel, a truly heavenly redeemer known to Israel as the archangel Michael.

- ^ Reinhard Gregor Kratz, Hermann Spieckermann: Götterbilder, Gottesbilder, Weltbilder: Griechenland und Rom, Judentum, Christentum und Islam. Mohr Siebeck, 2006, ISBN 978-3-16-148807-8 (German)

- ^ Sanhedrin 38b and Avodah Zerah 3b.

- ^ Aleksander R. Michalak, Angels as Warriors in Late Second Temple Jewish Literature, Tuebingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2012.

- ^ Hannah Darrell D., Michael and Christ: Michael Traditions and Angel Christology in Early Christianity, Tuebingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1999

- ^ cf. Sanhedrin 95b

- ^ Copleston, Frederick Charles (2003). A history of philosophy, Volume 1. Continuum International Publishing Group, p. 460. ISBN 0-8264-6895-0

- ^ Friedlander, Gerald. Pirke de Rabbi Eliezer Varda Books

- ^ Margaretha, Evans, Annette Henrietta (1 March 2007). The development of Jewish ideas of angels : Egyptian and Hellenistic connections, ca. 600 BCE to ca. 200 CE (Thesis).

- ^ Barker, Margaret (2004). An Extraordinary Gathering of Angels, M Q Publications.

- ^ "LA FIGURA DELL'ANGELO NELLA CIVILTA' PALEOCRISTIANA – PROVERBIO CECILIA – TAU – Libro". 27 December 2008. Archived from the original on 27 December 2008. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Muehlberger, Ellen (2013). Angels in late ancient Christianity. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-993193-4. OCLC 806291246.

- ^ MARTIN, DALE BASIL. "When Did Angels Become Demons?" Journal of Biblical Literature, vol. 129, no. 4, 2010, pp. 657–677. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25765960. Accessed 26 June 2021. p. 664

- ^ Loren T. Stuckenbruck; Gabriele Boccaccini (2016). Enoch and the Synoptic Gospels: Reminiscences, Allusions, Intertextuality. SBL Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-884-14118-1.

- ^ Loren T. Stuckenbruck; Gabriele Boccaccini (2016). Enoch and the Synoptic Gospels: Reminiscences, Allusions, Intertextuality. SBL Press. p. 112-113. ISBN 978-0-884-14118-1.

- ^ Loren T. Stuckenbruck; Gabriele Boccaccini (2016). Enoch and the Synoptic Gospels: Reminiscences, Allusions, Intertextuality. SBL Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-884-14118-1.

- ^ Augustine, En. in Ps. 103, 1, 15: PL 37, 1348

- ^ "A ZENIT DAILY DISPATCH". www.ewtn.com.

- ^ Ludlow, Morwenna (2012). Brakke, David (ed.). "Demons, Evil, and Liminality in Cappadocian Theology" (PDF). Journal of Early Christian Studies. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. 20 (2): 179–211 [183]. doi:10.1353/earl.2012.0014. hdl:10871/15370. ISSN 1067-6341. S2CID 145816767. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ Proverbio(2007), pp. 29–38; cf. summary in Libreria Hoepli and review in La Civiltà Cattolica, 3795–3796 (2–16 August 2008), pp. 327–328.

- ^ Pope Gregory I; David Hurst (OSB.) (1990). "Homily 34". Forty Gospel Homilies. Cistercian Publications. p. 287. ISBN 978-0-87907-623-8.

You should be aware that the word “angel” denotes a function rather than a nature. Those holy spirits of heaven have indeed always been spirits. They can only be called angels when they deliver some message. Moreover, those who deliver messages of lesser importance are called angels; and those who proclaim messages of supreme importance are called archangels. And so it was that not merely an angel but the archangel Gabriel was sent to the Virgin Mary.

- ^ Thomas Aquinas. "46". Summa contra Gentiles. 2.

- ^ Thomas Aquinas. Summa Theologica. Treatise on Angels. Newadvent.org.

- ^ Aquinas, Thomas. De substantiis separatis. Josephkenny.joyeurs.com. Archived from the original on 12 December 2010.

- ^ "BibleGateway, Matthew 24:36". Biblegateway.com. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Angels". www.newadvent.org.

- ^ "BibleGateway, Luke 22:43". Biblegateway.com. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Ann Ball, 2003 Encyclopedia of Catholic Devotions and Practices ISBN 0-87973-910-X page 123

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Angels Participate In History Of Salvation". Vatican.va. 6 August 1986. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ "Directory on popular piety and the liturgy. Principles and guidelines". www.vatican.va.

- ^ Swedenborg, Emanuel. Heaven and Hell, 1758. Rotch Edition (revised). New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1907, in The Divine Revelation of the New Jerusalem (2012), n. 74.

- ^ Arcana Coelestia, n. 459.

- ^ Heaven and Hell, n. 51–53.

- ^ Heaven and Hell, n. 311

- ^ Heaven and Hell, n. 416

- ^ Heaven and Hell, n. 387–393.

- ^ Swedenborg, Emanuel. Heavenly Arcana (or Arcana Coelestia), 1749–58 (AC). Rotch Edition (revised). New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1907, in The Divine Revelation of the New Jerusalem (2012), n. 8192.3.

- ^ Heaven and Hell, n. 291–298.

- ^ Arcana Coelestia, n. 50, 697, 968.

- ^ Arcana Coelestia, n. 227.

- ^ Arcana Coelestia, n. 784.2.

- ^ Heaven and Hell, n. 76.

- ^ Arcana Coelestia, n. 5992.3.

- ^ "God's messengers, those individuals whom he sends (often from his personal presence in the eternal worlds), to deliver his messages (Luke 1:11–38); to minister to his children (Acts 10:1–8, Acts 10:30–32); to teach them the doctrines of salvation (Mosiah 3); to call them to repentance (Moro. 7:31); to give them priesthood and keys (D.&C. 13; 128:20–21); to save them in perilous circumstances (Nehemiah 3:29–31; Daniel 6:22); to guide them in the performance of his work (Genesis 24:7); to gather his elect in the last days (Matthew 24:31); to perform all needful things relative to his work (Moro. 7:29–33)—such messengers are called angels.".

- ^ Jump up to: a b "LDS Bible Dictionary-Angels". Scriptures.lds.org. 21 February 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Doctrine and Covenants 130:4–5.

- ^ The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints "Chapter 6: The Fall of Adam and Eve," Gospel Principles (Salt Lake City, Utah: LDS Church, 2011) pp. 26–30.

- ^ "D&C 107:24". Scriptures.lds.org. 21 February 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Mark E. Petersen, "Adam, the Archangel", Ensign, November 1980.

- ^ "Joseph Smith–History 1:30–33". Scriptures.lds.org. 21 February 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ "D&C 110". Scriptures.lds.org. 21 February 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Robert J. Matthews, "The Fulness of Times", Ensign, December 1989.

- ^ Syed Anwer Ali Qurʼan, the Fundamental Law of Human Life: Surat ul-Faateha to Surat-ul-Baqarah (sections 1–21) Syed Publications 1984 University of Virginia Digitalized 22. Okt. 2010 p. 121

- ^ S.R. Burge Journal of Qurʼanic Studies The Angels in Sūrat al-Malāʾika: Exegeses of Q. 35:1 Sep 2011. vol. 10, No. 1 : pp. 50–70

- ^ Stephen Burge Angels in Islam: Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti's al-Haba'ik fi akhbar al-mala'ik Routledge 2015 ISBN 978-1-136-50473-0 p. 23

- ^ Stephen Burge Angels in Islam: Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti's al-Haba'ik fi akhbar al-mala'ik Routledge 2015 ISBN 978-1-136-50473-0 p. 79

- ^ Stephen Burge Angels in Islam: Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti's al-Haba'ik fi akhbar al-mala'ik Routledge 2015 ISBN 978-1-136-50473-0 p. 29

- ^ Stephen Burge Angels in Islam: Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti's al-Haba'ik fi akhbar al-mala'ik Routledge 2015 ISBN 978-1-136-50473-0 p. 22

- ^ Stephen Burge Angels in Islam: Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti's al-Haba'ik fi akhbar al-mala'ik Routledge 2015 ISBN 978-1-136-50473-0 pp. 97-99

- ^

- Quran 35:1

- Esposito (2002b, pp. 26–28)

- W. Madelung. "Malā'ika". Encyclopaedia of Islam Online.

- Gisela Webb. "Angel". Encyclopaedia of the Qurʼan Online.

- ^ Cenap Çakmak Islam: A Worldwide Encyclopedia [4 volumes] ABC-CLIO, 18.05.2017 ISBN 9781610692175 p. 140

- ^ Jane Dammen McAuliffe Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān Volume 3 Georgetown University, Washington DC p. 45

- ^ Stephen Burge Angels in Islam: Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti's al-Haba'ik fi akhbar al-mala'ik 2015 ISBN 978-1-136-50473-0 part 1.1 and 1.2.

- ^ Patrick Hughes, Thomas Patrick Hughes Dictionary of Islam Asian Educational Services 1995 ISBN 978-8-120-60672-2 page 73

- ^ Guessoum, Nidhal (2010). Islam's Quantum Question: Reconciling Muslim Tradition and Modern Science. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-0-85773-075-6.

- ^ MARTIN, DALE BASIL. “When Did Angels Become Demons?” Journal of Biblical Literature, vol. 129, no. 4, 2010, pp. 657–677. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25765960. Accessed 28 June 2021.

- ^ Aristotle. Metaphysics. 1072a ff.

- ^ Aristotle. Metaphysics. 1073a13 ff.

- ^ Abdullah Saeed Islamic Thought: An Introduction Routledge 2006 ISBN 9781134225651 p. 101

- ^ Mark Verman The Books of Contemplation: Medieval Jewish Mystical Sources SUNY Press 1992 ISBN 9780791407196 p. 129

- ^ "Sri Granth: Sri Guru Granth Sahib". srigranth.org. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ^ "Sri Granth: Sri Guru Granth Sahib". srigranth.org. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ^ "Sri Granth: Sri Guru Granth Sahib". srigranth.org. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ^ "Strong's Hebrew: 691. אֶרְאֵל (erel) – perhaps a hero". biblesuite.com.

- ^ "Strong's Hebrew: 2830. חַשְׁמַל (chashmal) – perhaps amber". biblesuite.com.

- ^ "Strong's Hebrew: 3742. כְּרוּב (kerub) – probably an order of angelic beings". biblesuite.com.

- ^ Hodson, Geoffrey, Kingdom of the Gods ISBN 0-7661-8134-0—Has color pictures of what Devas supposedly look like when observed by the third eye—their appearance is reputedly like colored flames about the size of a human. Paintings of some of the devas claimed to have been seen by Hodson from his book Kingdom of the Gods:

- ^ "Eskild Tjalve's paintings of devas, nature spirits, elementals and fairies". 21 November 2002. Archived from the original on 21 November 2002. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Powell, A.E. The Solar System London:1930 The Theosophical Publishing House (A Complete Outline of the Theosophical Scheme of Evolution) See "Lifewave" chart (refer to index)

- ^ Betz, Hans (1996). The Greek Magical Papyri In Translation. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226044477. Entries: "Introduction to the Greek Magical Papyri" and "PGM III. 1-164/fourth formula".

- ^ James M. Robinson (1988). The Nag Hammadi Library. Read online for free at the Internet Archive.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Basava Journal, Volume 19. Basava Samiti, 1994 (Bangalore, India).

- ^ Peace & purity: the story of the Brahma Kumaris : a spiritual revolution By Liz Hodgkinson

- ^ Smith, Peter (2000). "angels". A concise encyclopedia of the Baháʼí Faith. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. pp. 38–39. ISBN 1-85168-184-1.

- ^ "Tablet of the Maiden". bahai-library.com.

- ^ "Because angels are purely spiritual creatures without bodies, there is no sexual difference between them. There are no male or female angels; they are not distinguished by gender.", p. 10, "Catholic Questions, Wise Answers", Ed. Michael J. Daley, St. Anthony Messenger Press, 2001, ISBN 0867163984, 9780867163988. See also Catholic Answers, which gives the standard, unchanged, Catholic position.

- ^ "Angel", The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia James Orr, editor, 1915 edition.

- ^ Proverbio (2007), pp. 81–89; cf. review in La Civiltà Cattolica, 3795–3796 (2–16 August 2008), pp. 327–328.

- ^ Proverbio (2007) p. 66.

- ^ Proverbio (2007), pp. 90–95

- ^ Proverbio (2007) p. 34.

- ^ "History of the Church, 3:392". Institute.lds.org. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

Further reading[]

- Bamberger, Bernard Jacob, (15 March 2006). Fallen Angels: Soldiers of Satan's Realm. Jewish Publication Society of America. ISBN 0-8276-0797-0

- Barker, Margaret (2004). An Extraordinary Gathering of Angels, M Q Publications. ISBN 9781840726800

- Bennett, William Henry (1911), , in Chisholm, Hugh (ed.), Encyclopædia Britannica, 2 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 4–6

- Briggs, Constance Victoria, 1997. The Encyclopedia of Angels : An A-to-Z Guide with Nearly 4,000 Entries. Plume. ISBN 0-452-27921-6.

- Bunson, Matthew, (1996). Angels A to Z: A Who's Who of the Heavenly Host. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0-517-88537-9.

- Cheyne, James Kelly (ed.) (1899). Angel. Encyclopædia Biblica. New York, Macmillan.

- Cruz, Joan Carroll, OCDS, 1999. Angels and Devils. TAN Books and Publishers, Inc. ISBN 0-89555-638-3

- Davidson, A. B. (1898). "Angel". In James Hastings (ed.). A Dictionary of the Bible. I. pp. 93–97.

- Davidson, Gustav, (1967). A Dictionary of Angels: Including the Fallen Angels. Free Press. ISBN 0-02-907052-X

- Driver, Samuel Rolles (Ed.) (1901) The book of Daniel. Cambridge UP.

- Graham, Billy, 1994. Angels: God's Secret Agents. W Pub Group; Minibook edition. ISBN 0-8499-5074-0

- Guiley, Rosemary, 1996. Encyclopedia of Angels. ISBN 0-8160-2988-1

- Jastrow, Marcus, 1996, A dictionary of the Targumim, the Talmud Bavli and Yerushalmi, and the Midrashic literature compiled by Marcus Jastrow, PhD., Litt.D. with and index of Scriptural quotatons, Vol 1 & 2, The Judaica Press, New York

- Kainz, Howard P., "Active and Passive Potency" in Thomistic Angelology Martinus Nijhoff. ISBN 90-247-1295-5

- Kreeft, Peter J. 1995. Angels and Demons: What Do We Really Know About Them? Ignatius Press. ISBN 0-89870-550-9

- Leducq, M. H. (1853). "On the Origin and Primitive Meaning of the French word Ange". Proceedings of the Philological Society. 6 (132).

- Lewis, James R. (1995). Angels A to Z. Visible Ink Press. ISBN 0-7876-0652-9

- Melville, Francis, 2001. The Book of Angels: Turn to Your Angels for Guidance, Comfort, and Inspiration. Barron's Educational Series; 1st edition. ISBN 0-7641-5403-6

- Michalak, Aleksander R. (2012), Angels as Warriors in Late Second Temple Jewish Literature.Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-151739-6.

- Muehlberger, Ellen (2013). Angels in Late Ancient Christianity. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199931934

- Oosterzee, Johannes Jacobus van. Christian dogmatics: a text-book for academical instruction and private study. Trans. John Watson Watson and Maurice J. Evans. (1874) New York, Scribner, Armstrong.

- Proverbio, Cecilia (2007). La figura dell'angelo nella civiltà paleocristiana (in Italian). Assisi, Italy: Editrice Tau. ISBN 978-88-87472-69-1.

- Ronner, John, 1993. Know Your Angels: The Angel Almanac With Biographies of 100 Prominent Angels in Legend & Folklore-And Much More! Mamre Press. ISBN 0-932945-40-6.

- Smith, George Adam (1898) The book of the twelve prophets, commonly called the minor. London, Hodder and Stoughton.

- Smith, William Robertson (1878), , in Baynes, T. S. (ed.), Encyclopædia Britannica, 2 (9th ed.), New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, p. 26–28

- Swedenborg E. Heaven and its Wonders and Hell From Things Heard and Seen (Swedenborg Foundation 1946), ISBN 0-554-62056-1 (Detailed information on angels and their life in heaven)

- Swedenborg, E. Wisdom's Delight in Marriage ("Conjugial") Love: Followed by Insanity's Pleasure in Promiscuous Love (Swedenborg Foundation 1979 ISBN 0-87785-054-2) (Extensive review of angelic marriage)

- von Heijne, Camilla, 2010. The Messenger of the Lord in Early Jewish Interpretations of Genesis. BZAW 412. De Gruyter, Berlin/New York, ISBN 978-3-11-022684-3

- von Heijne, Camilla, 2015 "Angels" pp. 20–24 in The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Bible and Theology, vol. 1. Oxford University Press, New York. ISBN 978-0-19-023994-7

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Angels. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Angels |

- Coptic Doxology of Heavenly Order

- Zoroastrian angels

- Jewish Encyclopedia entry on angels

- Directory on popular piety and the liturgy. Principles and guidelines Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments. Directory of Popular Piety and the Liturgy, §§ 212–217, "The Holy Angels, Vatican City, December 2001]

- Angels, BBC Radio 4 discussion with Martin Palmer, Valery Rees & John Haldane (In Our Time, Mar. 24, 2005)

- Angels

- Heraldic charges

- Heaven in Christianity