Anthropodermic bibliopegy

Anthropodermic bibliopegy is the practice of binding books in human skin. As of May 2019, The Anthropodermic Book Project[1] has examined 31 out of 50 books in public institutions supposed to have anthropodermic bindings, of which 18 have been confirmed as human and 13 have been demonstrated to be animal leather instead.[2]

Terminology[]

'Bibliopegy' (/ˌbɪbliˈɒpɪdʒi/ BIB-lee-OP-i-jee) is a rare[3][a] synonym for 'bookbinding'. It combines the Ancient Greek βιβλίον (biblion, "book") and πηγία (pegia, from pegnynai, "to fasten").[5] The earliest reference in the Oxford English Dictionary dates from 1876; Merriam-Webster gives the date of first use as c. 1859[6] and the OED records an instance of 'bibliopegist' for a bookbinder from 1824.

The word 'anthropodermic' (/ˌænθroʊpəˈdɜːrmɪk/ AN-throh-pə-DUR-mik), combining the Ancient Greek ἄνθρωπος (anthropos, "man" or "human") and δέρμα (derma, "skin"), does not appear in the Oxford English Dictionary and appears to be unused in contexts other than bookbinding. The phrase "anthropodermic bibliopegy" has been used at least since Lawrence S. Thompson's article on the subject, published in 1946.[7] The practice of binding a book in the skin of its author – as with The Highwayman – has been called 'autoanthropodermic bibliopegy'[8] (from αὐτός, autos, meaning "self").

History[]

An early reference to a book bound in human skin is found in the travels of Zacharias Conrad von Uffenbach. Writing about his visit to Bremen in 1710:

(We also saw a little duodecimo, Molleri manuale præparationis ad mortem. There seemed to be nothing remarkable about it, and you couldn't understand why it was here until you read in the front that it was bound in human leather. This unusual binding, the like of which I had never before seen, seemed especially well adapted to this book, dedicated to more meditation about death. You would take it for pig skin.)

— translated by Lawrence S. Thompson, Religatum de Pelle Humana[9]

During the French Revolution, there were rumours that a tannery for human skin had been established at Meudon outside Paris.[10] The Carnavalet Museum owns a volume containing the French Constitution of 1793 and Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen described as 'passing for being made in human skin imitating calf'.[10]

The majority of well-attested anthropodermic bindings date from the 19th century.

Examples[]

Criminals[]

Surviving examples of human skin bindings have often been commissioned, performed, or collected by medical doctors, who have access to cadavers, sometimes those of executed criminals, such as the case of John Horwood in 1821 and William Corder in 1828.[15] The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh preserves a notebook bound in the skin of the murderer William Burke after his execution and subsequent public dissection by Professor Alexander Monro in 1829.[16] (Note that Horwood, Corder, and Burke were all hanged and not flayed.)

What Lawrence Thompson called "the most famous of all anthropodermic bindings" is exhibited at the Boston Athenaeum, titled The Highwayman: Narrative of the Life of James Allen alias George Walton. It is by James Allen, who made his deathbed confession in prison in 1837 and asked for a copy bound in his own skin to be presented to a man he once tried to rob and admired for his bravery, and another one for his doctor.[17] Once he died, a piece of his back was taken to a tannery and utilized for the book.[18]

Dance of Death[]

An exhibition of fine bindings at the Grolier Club in 1903 included, in a section of 'Bindings in Curious Materials', three editions of Holbein's 'Dance of Death' in 19th-century human skin bindings;[19] two of these now belong to the John Hay Library at Brown University. Other examples of the Dance of Death include an 1856 edition offered at auction by Leonard Smithers in 1895[20] and an 1842 edition from the personal library of Florin Abelès was offered at auction by Piasa of Paris in 2006. Bookbinder Edward Hertzberg describes the Monastery Hill Bindery having been approached by "[a]n Army Surgeon ... with a copy of Holbein's Dance of Death with the request that we bind it in a piece of human skin, which he brought along."[21]

Other examples[]

Another tradition, with less supporting evidence, is that books of erotica[22][23] [24] have been bound in human skin.

A female admirer of the French astronomer Camille Flammarion supposedly bequeathed her skin to bind one of his books. At Flammarion's observatory, there is a copy of his La pluralité des mondes habités on which is stamped reliure en peau humaine 1880 ("human skin binding, 1880").[25] This story is sometimes told instead about Les terres du ciel and the donor named as the Comtesse de Saint-Ange.

The Newberry Library in Chicago owns an Arabic manuscript written in 1848, with a handwritten note that it is bound in human skin, though "it is the opinion of the conservation staff that the binding material is not human skin, but rather highly burnished goat". This book is mentioned in the novel The Time Traveler's Wife, much of which is set in the Newberry.[26]

The National Library of Australia holds a 19th-century poetry book with the inscription "Bound in human skin" on the first page.[27] The binding was performed 'before 1890' and identified as human skin by pathologists in 1992.[28]

A portion of the binding in the copy of Dale Carnegie's Lincoln the Unknown that is part of Temple University's Charles L. Blockson Collection was "taken from the skin of a Negro at a Baltimore Hospital and tanned by the Jewell Belting Company".[29]

Identification[]

The identification of human skin bindings has been attempted by examining the pattern of hair follicles, to distinguish human skin from that of other animals typically used for bookbinding, such as calf, sheep, goat, and pig. This is a necessarily subjective test, made harder by the distortions in the process of treating leather for binding. Testing a DNA sample is possible in principle, but DNA can be destroyed when skin is tanned, degrades over time, and can be contaminated by human readers.[30]

Instead, peptide mass fingerprinting (PMF) and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) have recently been used to identify the material of bookbindings. A tiny sample is extracted from the book's covering and the collagen analysed by mass spectrometry to identify the variety of proteins which are characteristic of different species. PMF can identify skin as belonging to a primate; since monkeys were almost never used as a source of skin for bindings, this implies human skin.

The Historical Medical Library of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia owns five anthropodermic books, confirmed by peptide mass fingerprinting in 2015,[31] of which three were bound from the skin of one woman.[32] This makes it the largest collection of such books in one institution. The books can be seen in the associated Mütter Museum.

The John Hay Library at Brown University owns four anthropodermic books, also confirmed by PMF:[33] Vesalius's De Humani Corporis Fabrica, two nineteenth-century editions of Holbein's Dance of Death, and Mademoiselle Giraud, My Wife (1891).

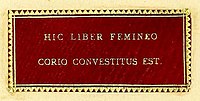

Three books in the libraries of Harvard University have been reputed to be bound in human skin, but peptide mass fingerprinting has confirmed only one,[34] Des destinées de l'ame by Arsène Houssaye], held in the Houghton Library.[35] (The other two books at Harvard were determined to be bound in sheepskin, the first being Ovid's Metamorphoses,[36] held in the Countway Library, the second being a treatise on Spanish law, Practicarum quaestionum cirva leges regias Hispaniae,[37] held in the library of Harvard Law School.[38])

The Harvard skin book belonged to Dr Ludovic Bouland of Strasbourg (died 1932), who rebound a second, De integritatis & corruptionis virginum notis,[39] now in the Wellcome Library in London. The Wellcome also owns a notebook labelled as bound in the skin of 'the Negro whose Execution caused the War of Independence', presumably Crispus Attucks, but the library doubts that it is actually human skin.

Confirmed examples[]

Supposed examples confirmed as animal skin[]

Unconfirmed but located examples[]

Ethical and legal issues[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (September 2016) |

- Repatriation and reburial of human remains

- Human trophy collecting

- Human Tissue Act 2004 (United Kingdom)

- Paul Needham, A Binding of Human Skin in the Houghton Library: A Recommendation (25 June 2014)

In popular culture[]

This article appears to contain trivial, minor, or unrelated references to popular culture. (September 2018) |

The binding of books in human skin is also a common element within horror films and works of fiction.

Fiction

- In H.P. Lovecraft's horror story 'The Hound' (1922), the narrator and his friend St John, who are graverobbers, have a collection of macabre artefacts. Amongst them, "A locked portfolio, bound in tanned human skin, held certain unknown and unnameable drawings which it was rumoured Goya had perpetrated but dared not acknowledge."[64]

- In David H. Keller's short story "Binding Deluxe", first published in Marvel Tales (May 1934),[65][66] a bookbinder uses the skins of the men she murders to create a "deluxe" binding for a set of Encyclopædia Britannica.

- In Brian Lumley's story 'Billy's Oak' (1970), a book, the Cthaat Aquadingen, is bound in human skin. Although over 400 years old, it still sweats.

- P. C. Hodgell's Kencyr series (1982 onwards) features "the Book Bound in Pale Leather", which appears to be bound in living human skin.

- Chuck Palahniuk's novel Lullaby (2002) features a book bound in human skin called "The Grimoire".

- In the novel The Journal of Dora Damage (2008) by Belinda Starling, a bookbinder is brought "leather" by a client with which to undertake a "special binding" of this nature.[67]

- In Linda Fairstein's mystery novel Lethal Legacy (2009), a book collector shows investigators an 1828 book of trial proceedings that is bound with the skin of a convicted murderer.

- In the novel The Eye of God (2013) by James Rollins, Vigor receives a package from Father Josip Tarasco that contains a skull and an ancient book bound in human skin.

- In The Book of Life (2014) by Deborah Harkness (the final book in the A Discovery of Witches trilogy) the book is made entirely of human / creature materials including the binding, ink, and paper.

- In Trudi Canavan's novel Thief’s Magic, a protagonist discovers a magical book made by a powerful sorcerer with skin, hair, bones and tendons from a talented bookbinder[68]

- In I Am Providence (2016) by Nick Mamatas, a book bound in human skin, whose owner is murdered, propels the plot.[69]

Television and cinema

- In the Evil Dead series of films and comic books originally created by Sam Raimi in 1981, a fictional Sumerian book called the Necronomicon Ex-Mortis is bound in human skin and inked with human blood.

- In the Disney film Hocus Pocus (1993), the eldest Sanderson sister's (played by Bette Midler) fictional spellbook is bound in a patchwork of human skin with an enchanted, moving human eye embedded in the cover.

- Peter Greenaway's 1996 film The Pillow Book contains a sequence in which the body of a writer's lover is exhumed by an obsessed publisher; and his skin, which she wrote upon after his death, is painstakingly tanned and bound into a book.

- The eponymous book in the Canadian television series Todd and the Book of Pure Evil (2010) is allegedly bound in human skin.

- In the episode "Like a Virgin" (2011) of the TV series Supernatural, the book containing the spell to release the Mother of All is printed (rather than bound) on human skin.

- In one episode of Truth Seekers (2020), a prologue scene depicts a sequence where a publisher is killed over the possession of pages of "Praecepta Mortuorum", a book written on sun-dried human skin.

Video games

- In the video game Shadow Hearts (2001), one of the characters is able to use a book bound from human skin as a weapon.[70]

- The video game Eternal Darkness: Sanity's Requiem (2002) centers around a book called the "Tome of Eternal Darkness" which is bound in human flesh.

- The video game "Assassin's Creed Unity" (2014) features the practice of binding books in human skins in a mission set in 18th century Franciade.

- In The Elder Scrolls, The Oghma Infinitum is a artifact of the deity known as "Herma-Mora", It is a book bound in human skin.

Notes[]

- ^ The Oxford English Dictionary places it in Frequency Band 2, for 'words which occur fewer than 0.01 times per million words in typical modern English usage. These are almost exclusively terms which are not part of normal discourse and would be unknown to most people. Many are technical terms from specialized discourses.'[4]

References[]

- ^ "The Anthropodermic Book Project". The Anthropodermic Book Project. Retrieved 2020-03-27.

- ^ The Anthropodermic Books Project, home page, checked 18 July 2019. Megan Rosenbloom clarifies in this interview with Joanna Ebenstein in The Morbid Anatomy Online Journal, 16 April 2020, that these figures do not include books tested from individuals' private collections, as opposed to libraries and museums.

- ^ "Google Ngram Viewer". books.google.com.

- ^ OED entry for bibliopegy, checked 1 September 2016.

- ^ OED entry for bibliopegy, checked 9 September 2016.

- ^ Merriam-Webster definition for bibliopegy, checked 9 September 2016.

- ^ Thompson 1946.

- ^ Thompson 1968, pp. 140–142.

- ^ Thompson 1968, p. 135.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rosenbloom, Lapham's Quarterly.

- ^ "Chirurgia è Graeco in Latinum conuersa". Smithsonian Libraries – Catalog. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ "Vesalius's De humani corporis fabrica". Classic Josiah Brown University Library Catalog. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ Sorgeloos 2012, p. 135–137.

- ^ "This may seem like a morbid question, but I'm curious. Does the Smithsonian have any books bound in human skin in its collection?". Turning the Book Wheel : Tumblr's blog of the Smithsonian Libraries. 30 April 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ "Killer cremated after 180 years". BBC News. 17 August 2004. Retrieved 4 July 2007.

- ^ "Pocketbook made from Burke's skin – Surgeons' Hall Museums, Edinburgh". museum.rcsed.ac.uk. Archived from the original on October 10, 2016.

- ^ Allen, James; Lincoln, Charles; Low Peter (25 August 2017). "Narrative of the life of James Allen, alias George Walton, alias Jonas Pierce, alias James H. York, alias Burley Grove, the highwayman: being his death-bed confession, to the warden of the Massachusetts State Prison [i.e. Charles Lincoln, Jr.]". Harrington & Co. Retrieved 25 August 2017 – via catalog.bostonathenaeum.org Library Catalog.

- ^ Boston Athenaem Skin Book. (2020). Atlas Obscura. Retrieved from https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/boston-athenaeum-skin-book

- ^ The Grolier Club of the City of New York. Exhibition of silver, embroidered and curious bookbindings, April 16 to May 9, 1903 ([New York City]: The De Vinne Press, [1903]), exhibits 177–179 (pp. 58–59).

- ^ Callum James, Leonard Smithers: Human Skin Binding, Front Free Endpaper (May 27, 2009)

- ^ Hertzberg, Edward (1933). Forty-four years as a bookbinder. Chicago: Ernst Hertzberg and Sons Monastery Hill Bindery. p. 43.

- ^ Thompson 1946, p. 98.

- ^ Graham 1965, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Joanna Ebenstein, Interview with Megan Rosenbloom, The Morbid Anatomy Online Journal (April 16, 2020): 'everyone knows about de Sade: Justine, and Juliette, but I can't find any actual Justine and Juliette anywhere in an actual public library, so if it exists at all it's probably in a private collection'

- ^ Aymard, Colette; Mayeur, Laurence-Anne (2016). "L'observatoire de Juvisy-sur-Orge, l'" univers d'un chercheur " à sauvegarder" [The Juvisy-sur-Orge observatory, a 'world of research' worthy of protection]. In situ: Revue des patrimoines (in French). 29 (29). doi:10.4000/insitu.13211.

- ^ "Time Traveler's Wife – Newberry". www.newberry.org. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ^ "Poems bound up in a human skin". Canberra Times. 8 August 2011. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016.

- ^ Gordon 2016, p. 122.

- ^ Temple University Libraries and Charles L. Blockson, Catalogue of the Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection: A Unit of the Temple University Libraries, Temple University Press, 1990, p. 16. ISBN 0877227497

- ^ The Anthropodermic Book Project, The Science, checked 13 September 2016.

- ^ Beth Lander, Fugitive Leaves

- ^ Beth Lander, The Skin She Lived In: Anthropodermic Books in the Historical Medical Library

- ^ John Hay Library.Frequently Asked Questions: Is it true the John Hay Library has books bound in human skin?

- ^ http://id.lib.harvard.edu/aleph/005786452/catalog

- ^ Cole, Heather. "Caveat Lecter", Houghton Library Blog. June 4, 2014.

- ^ http://id.lib.harvard.edu/aleph/005593425/catalog

- ^ http://id.lib.harvard.edu/aleph/004317553/catalog Practicarum quaestionum circa leges regias Hispaniae

- ^ Karen Beck (April 3, 2014). "852 RARE: Old Books, New Technologies, and "The Human Skin Book" at HLS". The Harvard Law School Library Blog. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- ^ http://search.wellcomelibrary.org/iii/encore/record/C__Rb1283248

- ^ Gordon 2016, p. 129.

- ^ Marvin 1994.

- ^ Grolier Club Library Catalogue Item Details, Marc Record only : "Human skin confirmed in Peptide Mass Fingerprinting analysis conducted by Dan Kirby Analytical Services"

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Schieszer, Ashleigh (30 November 2017). "Anthropodermic Bibliopegy, aka Human Skin Bindings". The Preservation Lab Blog. Preservation Lab. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ Schieszer, Ashleigh (2015), Poems on various subjects, religious and moral : Preservation Lab Treatment Report, Preservation Lab, p. 1: "There is a leather gold stamped label adhered to the pastedown that reads, "Given to the Department of Rare Books University of Cincinnati by Bert Smith's Acres of Books"

- ^ Goldschmidt, Ben (2013-10-23). "Rare Books Library home to skin-bound book". The News Record. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rosenbloom 2020, pp. 106–108.

- ^ Schieszer, Ashleigh (2015), Poems on various subjects, religious and moral : Preservation Lab ‐ Examination and Treatment Report, p. 6 (image of the bookplate)

- ^ Rosenbloom 2020, p. 106.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Lot 312 of 461: Poe's Gold Bug perhaps in human skin". PBA Galleries (Catalogue of Sale 592: Fine Books – Children's Literature & Illustrated Books – Counterculture Memorabilia, 08/11/2016). 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2018..

- ^ "Une histoire inédite de Poe: scarabée d'or et reliure en peau humaine". Bibliophilie.com (in French). 5 September 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ ""Pour en finir" avec les reliures en peau humaine? Epilogue". Bibliophilie.com (in French). 9 July 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ Colby, Christine (2 June 2016). "7 Times The Skin Of Executed Criminals Was Used To Bind Books". Crimefeed. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

Rosenbloom [Megan Rosenbloom, member of the Anthropodermic Book Project] says the Allen book has been verified as definitely bound in human flesh

. - ^ "HBM115: Bound in Walton et al". Here Be Monsters. 2019-03-27. Retrieved 2019-04-27. (Interview with Dawn Walus, Chief Conservator at the Boston Athenæum about the book.

- ^ French translation of Saggio intorno al luogo del seppellire (1774) by Scipione Piattoli. English translation of Vicq d'Azyr's book : An essay on the danger of interments in cities (New-York : William Grattan, 1824).

- ^ Sorgeloos 2012, pp. 135, 144–145, 155 (#45), 165 (ill. 44).

- ^ Sorgeloos 2012, p. 135, 155 (#45).

- ^ Royal Library of Belgium (11 October 2018). "Une reliure en peau humaine ?" [A Human Skin Bookbinding ?]. Facebook (in French). Retrieved 15 December 2018. (Video by the Royal Library of Belgium on its official Facebook page, presenting the book and announcing the shipping of leather fragment samples to "an American Lab" for testing.). Also available on Youtube on the official channel of KRB, 10 October 2018.

- ^ Royal Library of Belgium (31 October 2018). "Announcement of PMF results by the Royal Library of Belgium on the official Facebook page". Facebook (in French). Retrieved 15 December 2018.

Les analyses viennent d’arriver : il ne s’agit ni de mouton, ni d’un autre animal couramment utilisé pour les reliures, mais bien de peau humaine. (The analyzes just arrived: it is neither sheep nor another animal commonly used for bindings, but human skin.)

; Royal Library of Belgium (2018). "Un livre relié en peau humaine ?" [A Human Skin Bookbinding ?]. Youtube (in French). Retrieved 10 January 2019.Il s’agit bien de peau humaine. (This is human skin.)

. - ^ The Daily Californian, The truth of the human skin-bound book (video))

- ^ Jade Alburo, Scary Books from YRL, 31 October 2012

- ^ UCLA library catalogue, call number DG975.M532 R2 1676

- ^ Metzger, Consuela. "Human Skin Binding at UCLA? Say it's not so..." UCLA Library: Preservation Blog. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ "Treasures Revealed: 260 Years of Collecting at the American Philosophical Society". American Philosophical Society. Archived from the original on 19 September 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2021.. Click on the image "The New Testament, 1866" to see the caption.

- ^ H.P. Lovecraft, Dagon & Other Macabre Tales. Sauk City, WI: Arkham House, 1965, p. 153

- ^ "Binding Deluxe". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- ^ Revised version (1943) * "Bindings Deluxe". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- ^ Novák, Caterina (2013). "Those Very 'Other' Victorians: Interrogating Neo-Victorian Feminism in The Journal of Dora Damage" (PDF). Neo-Victorian Studies. 6 (2). ISSN 1757-9481. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ^ Canavan, Trudi (2014). Thief's Magic. Millennium's Rule (Book 1). Orbit. ISBN 978-0316209274.

My cover and pages are my skin. My binding is my hair, twisted together and sewn with needles fashioned from my bones and glue from tendons.

- ^ Pedersen, Nate (2016-09-08). ""I Am Providence": An Interview with Nick Mamatas". The Fine Books Blog. Fine Books & Collections. Retrieved 2018-12-23..

- ^ "Shadow Hearts – Equipment List – PlayStation 2 – By leonia19". gamefaqs.gamespot.com. Retrieved 2020-03-27.

Further reading[]

- The Anthropodermic Book Project

- Jim Chevallier, 'Human Skin: Books (In and On)', Sundries: An Eighteenth Century Newsletter, #26 (April 15, 2006)

- Anita Dalton, Anthropodermic Bibliopegy: A Flay on Words, Odd Things Considered, 9 November 2015

- Gordon, Jacob (2016). "In the Flesh? Anthropodermic Bibliopegy Verification and Its Implications". RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Cultural Heritage. 17 (2): 118–133. doi:10.5860/rbm.17.2.9664. ISSN 2150-668X.

- Graham, Rigby (1965). "Bookbinding with Human Skin" (PDF). The Private Library. series 1, 6 (1): 14–18. ISSN 0032-8898.

- Guelle, Laura Ann (December 2002). "Anthropodermic Book-Bindings". Transactions & Studies of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. series 5, 24: 85–89. ISSN 0010-1087. PMID 12800321. (discusses John Stockton Hough's books)

- Kerner, Jennifer (2019). Anthropodermic Bibliopegy: an Extensive Survey and Re-appraisal of the Phenomenon (Research Report). Université Paris-Nanterre.

- Kerner, Jennifer (2019). "Reliures de livres avec la peau du condamné : hommage et humiliation autour des corps criminels". In Vivas, Mathieu (ed.). (Re)lecture archéologique de la justice en Europe médiévale et moderne : actes du colloque international tenu à Bordeaux les 8–10 février 2017 (in French). Bordeaux: Ausonius. pp. 195–211. ISBN 978-2-35613-243-7.

- Marvin, Carolyn (May 1994). "The Body of the Text: Literacy's Corporeal Constant". Quarterly Journal of Speech. 80 (2): 129–149. doi:10.1080/00335639409384064. – also available on academia.edu

- Rosenbloom, Megan (Summer 2016). "A Book by its Cover: Identifying & Scientifically Testing the World's Books Bound in Human Skin" (PDF). The Watermark: Newsletter of the Archivists and Librarians in the History of the Health Sciences. 39 (3): 20–22. ISSN 1553-7641..

- Rosenbloom, Megan (19 October 2016). "A Book by Its Cover". Lapham’s Quarterly. Retrieved 24 December 2018..

- Rosenbloom, Megan (2020). Dark Archives: A Librarian's Investigation into the Science and History of Books Bound in Human Skin. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 9780374134709..

- Samuelson, Todd (2014). "Still Life". Printing History: The Journal of the American Printing History Association. new series, 16: 42–50.

- Smith, Daniel K. (2014). "Bound In Human Skin: A Survey of Examples of Anthropodermic Bibliopegy". In Joanna Ebenstein; Colin Dickey (eds.). The Morbid Anatomy Anthology (First ed.). Brooklyn, New York: Morbid Anatomy Press. ISBN 9780989394307.

- Sorgeloos, Claude (2012). "L'Histoire de la reliure de Josse Schavye" [The History of Bookbinding by Josse Schavye]. In Monte Artium (in French). 5: 119–167. doi:10.1484/J.IMA.1.103005. ISSN 2507-0312.

- Thompson, Lawrence S. (April 1946). "Tanned Human Skin". Bulletin of the Medical Library Association. 34 (2): 93–102. PMC 194573. PMID 16016722.

- Thompson, Lawrence S. (1968). "Religatum de Pelle Humana" (PDF). Bibliologia Comica, or, Humorous aspects of the caparisoning and conservation of books. Hamden (Conn.): Archon Books. pp. 119–160. (originally issued separately in 1949 as University of Kentucky Libraries Occasional Contributions no. 6)

To use with caution[]

- Harrison, Perry Neil (2017). "Anthropodermic Bibliopegy in the Early Modern Period". In Larissa Tracy (ed.). Flaying in the Pre-Modern World : Practice and Representation. Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK: D.S. Brewer. pp. 366–383. ISBN 9781843844525. (Read with caution: This work is mostly obsolete. The two examples of allegedly anthropodermic bindings cited by Harrison (Richeome's L'Idolatrie Huguenote from University of Memphis and L'office de l'Eglise en françois from Berkeley) have since been proven by PMF analysis to be not of human origin. See the Table Supposed examples confirmed as animal skin.)

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anthropodermic bibliopegy. |

- Bookbinding

- Human trophy collecting

- Leather

- Human skin