Antonov An-225 Mriya

| An-225 Mriya | |

|---|---|

| |

| The An-225 in current livery in 2012 | |

| Role | Outsize cargo freight aircraft |

| National origin | Soviet Union |

| Design group | Antonov |

| Built by | Antonov Serial Production Plant |

| First flight | 21 December 1988 |

| Status | In service |

| Primary user | Antonov Airlines |

| Produced | 1985 |

| Number built | 1 |

| Developed from | Antonov An-124 |

The Antonov An-225 Mriya (Ukrainian: Антонов Ан-225 Мрія, lit. 'dream' or 'inspiration'; NATO reporting name: Cossack) is a strategic airlift cargo aircraft that was designed by the Antonov Design Bureau in the Ukrainian SSR within the Soviet Union during the 1980s. It is powered by six turbofan engines and is the heaviest aircraft ever built, with a maximum takeoff weight of 640 tonnes (705 short tons; 1,410×103 lb). It also has the largest wingspan of any aircraft in operational service. The single example built has the Ukrainian civil registration UR-82060. A second airframe with a slightly different configuration[1] was partially built. Its construction was halted in 1994[1] because of lack of funding and interest, but revived briefly in 2009, bringing it to 60–70% completion.[2] On 30 August 2016, Antonov agreed to complete the second airframe for Airspace Industry Corporation of China (not to be confused with the Aviation Industry Corporation of China) as a prelude to commencing series production.[3]

The Antonov An-225 was initially developed as an enlargement of the Antonov An-124 to transport Buran-class orbiters. The only An-225 airplane was completed in 1988. After successfully fulfilling its Soviet military missions, it was mothballed for eight years. It was then refurbished and reintroduced, and is in commercial operation with Antonov Airlines, carrying oversized payloads.[4] The airlifter holds the absolute world record for an airlifted single-item payload of 189,980 kg (418,830 lb),[5][6] and an airlifted total payload of 253,820 kg (559,580 lb).[7][8] It has also transported a payload of 247,000 kg (545,000 lb) on a commercial flight.[9]

Development[]

The Antonov An-225 was designed to airlift the Energia rocket's boosters and the Buran-class orbiters for the Soviet space program. It was developed as a replacement for the Myasishchev VM-T. The An-225's original mission and objectives are almost identical to that of the United States' Shuttle Carrier Aircraft.[10][11] The lead designer of the An-225 (and the An-124) was Viktor Tolmachev.[12]

The An-225 first flew on 21 December 1988.[13] It was on static display at the Paris Air Show in 1989, and it flew during the public days at the Farnborough Air Show in 1990. Two aircraft were ordered, but only one An-225, (registration CCCP-82060, later UR-82060[14]) was finished. It can carry ultra-heavy and oversized freight weighing up to 250,000 kg (550,000 lb) internally[10] or 200,000 kg (440,000 lb) on the upper fuselage. Cargo on the upper fuselage can be 70 m (230 ft) long.[15]

The second An-225 was partially built during the late 1980s for the Soviet space program. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the cancellation of the Buran program, the lone operational An-225 was placed in storage in 1994.[16][17] The six Ivchenko-Progress engines were removed for use on An-124s, and the second uncompleted An-225 airframe was also stored. In the 1990s, a cargoliner bigger than the An-124 was clearly needed. The first An-225 was restored by 2001.[8][18]

By 2000, the need for additional An-225 capacity had become apparent, so the decision was made in September 2006 to complete the second An-225. That second airframe was scheduled for completion around 2008,[19] then delayed. By August 2009, the aircraft had not been completed and work had been abandoned.[4][20] In May 2011, the Antonov CEO reportedly said that the completion of a second An-225 Mriya transport aircraft with a carrying capacity of 250 tons requires at least $300 million, but if the financing is provided, its completion could be achieved in three years.[21] According to different sources, the second aircraft is 60–70% complete.[22]

Airspace Industry Corporation of China (AICC)'s president, Zhang You-Sheng, told a BBC reporter that AICC first contemplated cooperation with Antonov in 2009 and contacted them in 2011. AICC intends to modernize the second unfinished An-225 and develop it into an air launch to orbit platform for commercial satellites at altitudes up to 12,000 m (39,000 ft).[13]

In April 2013, the Russian government announced plans to revive Soviet-era air launch projects that would use a purpose-built modification to the An-225 as a midair launchpad.[23][needs update]

In August 2016, representatives from Ukraine's Antonov and AICC, an import-export company operating out of Hong Kong,[24] signed an agreement to recommence production of the An-225, with China now planning to procure and fly the first model by 2019.[25][26] The aviation media cast doubt on the production restart, indicating that due to the ongoing Russia–Ukraine conflict, needed parts from Russia are unavailable, although they could be made in China instead.[27]

On 25 March 2020, the freighter commenced a series of test flights from Hostomel Airport near Kyiv, after more than a year out of service, for the installation of a domestically designed power management and control system.[28]

Design[]

Based on Antonov's earlier An-124, the An-225 has fuselage barrel extensions added fore and aft of the wings. The wings also received root extensions to increase span. The wings are anhedral.[29][18] The flight control surfaces are controlled via fly-by-wire and triple-redundant hydraulics.[8][30] Two more Progress D-18T turbofan engines were added to the new wing roots, bringing the total to six. An increased-capacity landing gear system with 32 wheels was designed, some of which are steerable, enabling the aircraft to turn within a 60-metre-wide (200 ft) runway. Like its An-124 predecessor, the An-225 has nose gear designed to "kneel" so cargo can be more easily loaded and unloaded.[8] Unlike the An-124, which has a rear cargo door and ramp, the An-225 design left these off to save weight, and the empennage design was changed from a single vertical stabilizer to a twin tail with an oversized, swept-back horizontal stabilizer. The twin tail was essential to enable the plane to carry large, heavy external loads that would disturb the airflow around a conventional tail. Unlike the An-124, the An-225 was not intended for tactical airlifting and is not designed for short-field operation.[10]

Initially, the An-225 had a maximum gross weight of 600 t (660 short tons; 590 long tons), but from 2000 to 2001, the aircraft underwent modifications at a cost of US$20M such as the addition of a reinforced floor, which increased the maximum gross weight to 640 t (710 short tons; 630 long tons).[31][32][33]

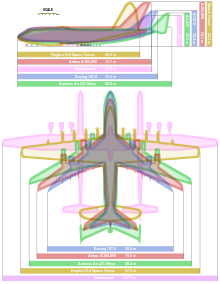

Both the earlier and later takeoff weights establish the An-225 as the world's heaviest aircraft, being heavier than the double-deck Airbus A380. It is surpassed in other size-related categories, but Airbus claims to have improved upon the An-225's maximum landing weight by landing an A380 at 591.7 tonnes (1,304,000 lb) during tests,[34] and the Hughes H-4 Hercules, known as the Spruce Goose, has a greater wingspan and a greater overall height, but the Spruce Goose is 20% shorter and overall lighter, due to the materials used in its construction. In addition, the H-4 only flew once and for less than a minute, making the An-225 the largest aircraft in the world to fly multiple times.[8][35]

The An-225's pressurized cargo hold is 1,300 m3 (46,000 cu ft) in volume; 6.4 m (21 ft 0 in) wide, 4.4 m (14 ft) high, and 43.35 m (142 ft 3 in) long[8][36][37] — longer than the first flight of the Wright Flyer.[38][39][40]

Operational history[]

During the last years of the Soviet space program, the An-225 was employed as the prime method of transporting Buran-class orbiters.[35]

Antonov commercialization[]

In the late 1980s, the Soviet government was looking for a way to generate revenue from its military assets. In 1989, the Antonov Design Bureau set up a holding company as a heavy airlift shipping corporation under the name "Antonov Airlines", based in Kyiv, Ukraine, and operating from London Luton Airport in partnership with Air Foyle HeavyLift.[15][41]

The company began operations with a fleet of four An-124-100s and three Antonov An-12s, but a need for aircraft larger than the An-124 became apparent in the late 1990s. In response, the original An-225 was re-engined, modified for heavy cargo transport, and placed back in service under the management of Antonov Airlines.

On 23 May 2001, the An-225 received its type certificate from the Interstate Aviation Committee Aviation Register (IAC AR).[42] On 11 September 2001, carrying four main battle tanks[8] at a record load of 253.82 tonnes (279.79 short tons) of cargo,[7] the An-225 flew at an altitude of up to 10,750 m (35,270 ft)[43] over a closed circuit of 1,000 km (620 mi) at a speed of 763.2 km/h (474.2 mph).[44][45] The hire cost can be $30,000 per hour.[46]

The An-225 attracts a high degree of public interest, so much that it has managed to attain a global following due to its size and its uniqueness. People frequently visit airports to see its scheduled arrivals and departures, such as in Perth, Australia in May 2016, when a crowd of more than 15,000 people gathered at Perth Airport.[47][better source needed]

Contracted flights[]

The type's first flight in commercial service departed from Stuttgart, Germany, on 3 January 2002, and flew to Thumrait, Oman, with 216,000 prepared meals for American military personnel based in the region. This vast number of ready meals was transported on 375 pallets and weighed 187.5 tons.[48]

The An-225 has since become the workhorse of the Antonov Airlines fleet, transporting objects once thought impossible to move by air, such as 150-tonne generators. It has become an asset to international relief organizations for its ability to quickly transport huge quantities of emergency supplies during disaster-relief operations.[49]

The An-225 has been contracted by the Canadian and U.S. governments to transport military supplies to the Middle East in support of coalition forces.[49] An example of the cost of shipping cargo by An-225 was over 2 million DKK (about €266,000) for flying a chimney duct from Billund, Denmark, to Kazakhstan in 2004.[50]

On 11 August 2009, the heaviest single cargo item ever sent by air freight was loaded onto the An-225. At 16.23 m (53 ft 3 in) long and 4.27 m (14 ft 0 in) wide, its consignment, a generator for a gas power plant in Armenia along with its loading frame, weighed in at a record 189 tonnes (417,000 lb).[5][6]

During 2009, the An-225 was painted in a new blue and yellow paint scheme,[51] after Antonov ceased cooperation with AirFoyle and partnered with Volga-Dnepr in 2006.[52]

On 11 June 2010, the An-225 carried the world's longest piece of air cargo, two 42.1 m (138 ft) test wind turbine blades from Tianjin, China, to Skrydstrup, Denmark.[53][54]

The An-225 participated in the COVID-19 pandemic relief effort, conducting flights to deliver medical supplies from China to other parts of the world.[55][56][57][58]

Operators[]

- Antonov Airlines (former operator) for Soviet Buran program; the company (and aircraft) passed to Ukraine after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Specifications (An-225 Mriya)[]

Data from Vectorsite,[10] Antonov's Heavy Transports,[59] and others[8][18][36][37]

General characteristics

- Crew: 6

- Length: 84 m (275 ft 7 in)

- Wingspan: 88.4 m (290 ft 0 in)

- Height: 18.1 m (59 ft 5 in)

- Wing area: 905 m2 (9,740 sq ft)

- Aspect ratio: 8.6

- Empty weight: 285,000 kg (628,317 lb)

- Max takeoff weight: 640,000 kg (1,410,958 lb)

- Fuel capacity: more than 300,000 kg (661,000 lb)[60]

- Cargo hold: volume 1,300 m3 (46,000 cu ft), 43.35 m (142.2 ft) long × 6.4 m (21 ft) wide × 4.4 m (14 ft) tall

- Powerplant: 6 × Progress D-18T turbofans, 229.5 kN (51,600 lbf) thrust each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 850 km/h (530 mph, 460 kn)

- Cruise speed: 800 km/h (500 mph, 430 kn)

- Range: 15,400 km (9,600 mi, 8,300 nmi) with maximum fuel; range with 200 tonnes payload: 4,000 km (2,500 mi)

- Service ceiling: 11,000 m (36,000 ft)

- Wing loading: 662.9 kg/m2 (135.8 lb/sq ft)

- Thrust/weight: 0.234

See also[]

- Air launch to orbit

- MAKS (spacecraft) – Proposed Soviet air-launched reusable launch system project

- Tupolev OOS – Soviet concept for an air-launched, single-stage-to-orbit spaceplane

- TTS-IS – Russian future very large wing-in-ground-effect, lifting-body cargo aircraft

- State Space Agency of Ukraine

Related development

- Antonov An-124 Ruslan – Soviet/Ukraine four–engine large military transport aircraft

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- Airbus Beluga – Outsize cargo version of the A300-600 airliner

- Beriev Be-2500 – Russian super heavy amphibious transport aircraft currently in design and development

- Boeing 747-8F – Wide-body airliner, current production series of the 747

- Boeing 747 Shuttle Carrier Aircraft – Extensively modified Boeing 747 airliners that NASA used to transport Space Shuttle orbiters

- Boeing Dreamlifter – Outsize cargo conversion of the 747-400

- Lockheed C-5 Galaxy – American heavy military transport aircraft

- Myasishchev VM-T – Conversion of Soviet M-4 Molot bomber to carry outsized cargo

- Scaled Composites Stratolaunch – Mother ship aircraft designed to launch spacecraft, the largest wingspan (117 meters) on any aircraft which has flown (2019)

Related lists

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Trimble, Steven (31 August 2016). "An-225 revival proposed in new Antonov-China pact". Flightglobal. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ^ Yeo, Mike (6 September 2016). "Antonov Sells Dormant An-225 Heavylifter Program to China". AINonline. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ^ Lin, Jeffrey; Singer, P. W. (8 September 2016). "China Will Resurrect The World's Largest Plane". Popular Science. Retrieved 15 December 2016.. Note that the company name is wrong. The official press release has the right name: [1]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "World's largest aircraft, An-225, emerges to set new lift record". Flightglobal. Flight International. 17 August 2009. Archived from the original on 20 August 2009. Retrieved 30 September 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cargo manifest picture Air Cargo News 13 November 2009. Retrieved: 30 May 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ukraine's An-225 aircraft sets new record for heaviest single cargo item transported by air Archived 30 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Eye for Transport, 18 August 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Payload record in the official FAI database". Archived from the original on 12 June 2013. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h An-225 (An-225-100) "Мрiя" Archived 31 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Russian Aviation Museum, 20 October 2001. Retrieved: 31 October 2010.

- ^ "An-225 sets new record for payload". Flightglobal. 29 June 2004. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Greg Goebel. "Antonov An-225 Mriya ("Cossack")". The Antonov Giants: An-22, An-124, & An-225. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ^ Greg Goebel. "The Soviet Buran shuttle program". Postscript: The Other Shuttles. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ^ "Volga-Dnepr Group Celebrates 80th Birthday of Legendary Chief Designer of the An-124 and An-225 Transport Aircraft". www.volga-dnepr.com. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Borys, Christian (7 May 2017). "The world's biggest plane may have a new mission". BBC. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ "Aviation Photo #1154941: Antonov An-225 Mriya - Antonov Design Bureau". airliners.net. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "AN-225 Mriya / Super Heavy Transport". Antonov ASTC. Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 21 April 2014.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- ^ Antonov An-225 Mriya. Airliners.net.

- ^ Fedykovych, Pavlo (31 August 2018). "World's biggest unfinished plane hidden in a hangar". CNN Travel. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Antonov An-225 Mriya (Cossack) Heavy Lift Strategic Long-Range Transport". Military Factory, 23 August 2012. Retrieved: 2 August 2020.

- ^ Antonov An-225 Mriya Aircraft History, Facts and Pictures. Aviationexplorer

- ^ The Mriya 2: Pictures Archived 18 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Buran-energia.com

- ^ webstudio, TAC. "Ukrainian Journal". ukrainianjournal.com. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ "Ukraine may finish the construction of second An-225 Mriya transport aircraft – News – Russian Aviation". Ruaviation.Com. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ Правительство задумалось о "Воздушном старте". Interfax (in Russian). 23 April 2013. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- ^ "A private company to run the world's largest transport aircraft production in China? The truth is…". Toutiao (in Chinese). 1 September 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ^ Jennings, Gareth (31 August 2016). "China and Ukraine agree to restart An-225 production". IHS Jane's. London. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ "ANTONOV Company signed Cooperation agreement on the AN−225 programme with AICC". ANTONOV Company. Kyiv. 31 August 2016. Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 6 September 2016.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- ^ Grady, Mary (14 September 2016). "World's Largest Airplane Back in Play". AVweb. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ David Kaminski-Morrow (26 March 2020). "An-225 returns to flight after modernisation". Flightglobal.

- ^ Jackson, Dave (2 December 2001). "Aerospaceweb.org | Ask Us - Wing Twist and Dihedral". www.aerospaceweb.org.

- ^ "Antonov An-225". www.copybook.com.

- ^ Forward, David C: "Antonov's Dream Machine", p. 23. Airways magazine, June 2004

- ^ Spaeth, Andreas: "When size matters", p. 29. Air International magazine, December 2009

- ^ Gordon, Yefim; Dmitriy and Sergey Komissarov: "The Six-Engined Dream", page 76. Antonov's Heavy Transports: The An-22, An-124/225 and An-70. Midland, 2004. ISBN 1-85780-182-2.

- ^ Learmount, David (3 June 2009). "Airbus reveals A380-linked pilot systems secrets". Flightglobal. London. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Antonov An-225 Mryia (Cossack)". The Aviation Zone. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "AN-225 Mriya" GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved: 6 September 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Antonov An 225" Archived 15 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine Air Charter Service. Retrieved: 6 September 2012.

- ^ "Exhibitions". si.edu. 28 April 2016. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ "100 Years Ago, the Dream of Icarus Became Reality." Archived 13 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine FAI NEWS, 17 December 2003. Retrieved: 5 January 2007.

- ^ Lindberg, Mark. "Century of Flight." Archived 4 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine Wings of History Museum, 2003. Retrieved: 27 August 2011.

- ^ "An-225 Mriya, NATO: Cossack". Goleta Air & Space Museum. Retrieved 31 March 2004.

- ^ "Type Certificates for Aircraft". Archived from the original on 30 April 2008. Retrieved 8 January 2007.

- ^ "Height record with 250t payload in the FAI database". Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- ^ "Speed record with 250t payload over 1000km closed circuit in the official FAI database". Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- ^ "Special planes: The Antonov-225 "Mriya"". European Tribune. 8 April 2006. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Skyba, Christian Borys / Pictures by Anton (5 May 2017). "The world's biggest plane may have a new mission". www.bbc.com.

- ^ "Antonov An-225 Mriya touches down in WA amid traffic chaos near Perth Airport". WANews.com. 16 May 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ "Antonov Airlines:An-225 Mriya". AirFoyle. Archived from the original on 23 May 2006. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Antonov An-225". Aircraft-Info.net. Archived from the original on 1 April 2004. Retrieved 15 February 2004.

- ^ Steelcon News Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. steelcon.com. Retrieved: 13 June 2010.

- ^ "Photo of the An-225 in new paint scheme". Spotters.net. 2009. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- ^ Ingram, Frederick C. Volga-Dnepr Group answers.com. Retrieved: 24 July 2010.

- ^ "Ukraine's Mriya An-225 aircraft sets new record". Kyiv Post. Interfax-Ukraine. 11 June 2010. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ^ "Geodis Wilson managed record-breaking airfreight move" (Press release). SNCF Geodis. 11 June 2010. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ^ Chase, Steven (27 April 2020). "World's biggest cargo plane to ship Chinese PPE to Quebec". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ^ Charpentreau, Clément (20 April 2020). "Antonov An-225 Mriya breaks two records in one week". Aerotime Hub. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ^ "Ukraine's Mega-Plane Works Overtime Through Pandemic". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 29 April 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ^ Holmes, Loren; Roth, Bill (1 May 2020). "World's largest cargo plane stops in Anchorage on its way to Canada with medical supplies". Anchorage Daily News. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ^ Gordon, Yefim (2004). Antonov's Heavy Transports: Big Lifters for War & Peace. Midland Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85780-182-8.

- ^ Jackson, Paul (ed): Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1995-1996, page 444. Jane's Information Group, 2011. ISBN 0710612621

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Antonov An-225 (category) |

| External media | |

|---|---|

| Images | |

| Video | |

- Antonov aircraft

- Buran program

- 1980s Soviet cargo aircraft

- Six-engined jet aircraft

- Aircraft first flown in 1988

- Aircraft related to spaceflight

- Twin-tail aircraft