Aquascaping

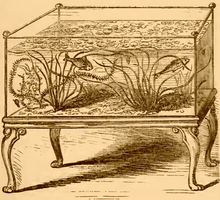

Aquascaping is the craft of arranging aquatic plants, as well as rocks, stones, cavework, or driftwood, in an aesthetically pleasing manner within an aquarium—in effect, gardening under water. Aquascape designs include a number of distinct styles, including the garden-like Dutch style and the Japanese-inspired nature style.[1] Typically, an aquascape houses fish as well as plants, although it is possible to create an aquascape with plants only, or with rockwork or other hardscape and no plants.

Aquascaping appears to have begun to be a popular hobby in the 1930s in the Netherlands, following the introduction of the Dutch style aquascaping techniques. With the increasing availability of mass-produced freshwater fishkeeping products and popularity of fishkeeping following the First World War, hobbyists began exploring the new possibilities of creating an aquarium that did not have fish as the main attraction.[2]

Although the primary aim of aquascaping is to create an artful underwater landscape, the technical aspects of tank maintenance and the growth requirements of aquatic plants are also taken into consideration.[3] Many factors must be balanced in the closed system of an aquarium tank to ensure the success of an aquascape. These factors include filtration, maintaining carbon dioxide at levels sufficient to support photosynthesis underwater, substrate and fertilization, lighting, and algae control.[4]

Aquascape hobbyists trade plants, conduct contests, and share photographs and information via the Internet.[5][6][7] The United States-based Aquatic Gardeners Association has about 1,200 members.[7]

Designs[]

Dutch style[]

The Dutch aquarium employs a lush arrangement in which multiple types of plants having diverse leaf colors, sizes, and textures are displayed much as terrestrial plants are shown in a flower garden. This style was developed in the Netherlands starting in the 1930s, as freshwater aquarium equipment became commercially available.[1] It emphasizes plants located on terraces of different heights, and frequently omits rocks and driftwood. Linear rows of plants running left-to-right are referred to as "Dutch streets".[8] Although many plant types are used, one typically sees neatly trimmed groupings of plants with fine, feathery foliage, such as Limnophila aquatica and various types of Hygrophila, along with the use of red-leaved Alternanthera reineckii, Ammania gracilis, and assorted Rotala for color highlights.[8] More than 80% of the aquarium floor is covered with plants, and little or no substrate is left visible.[8] Tall growing plants that cover the back glass originally served the purpose of hiding bulky equipment behind the tank.[1]

Japanese style[]

Nature style[]

A contrasting approach is the "nature aquarium" or Japanese style, introduced in the 1990s by Takashi Amano.[1] Amano's three-volume series, Nature Aquarium World, sparked a wave of interest in aquarium gardening, and he has been cited as having "set a new standard in aquarium management".[9] Amano's compositions drew on Japanese gardening techniques that attempt to mimic natural landscapes by the asymmetrical arrangement of masses of relatively few species of plants, and which set rules governing carefully selected stones or driftwood, usually with a single focal point. The objective is to evoke a terrestrial landscape in miniature, rather than a colourful garden. This style draws particularly from the Japanese aesthetic concepts of Wabi-sabi (侘寂), which focuses on transience and minimalism as sources of beauty. Plants with small leaves like Glossostigma elatinoides, Eleocharis acicularis, Eleocharis parvula, Echinodorus tenellus, Hemianthus callitrichoides, Riccia fluitans, small aquatic ferns, Staurogyne repens, and Java moss (Versicularia dubyana or Taxiphyllum barbieri) are often used to emulate grass or moss. Colours are more limited than in the Dutch style, and the hardscape is not completely covered. Fish, or freshwater shrimp such as Caridina multidentata and Neocaridina davidi, are usually selected to complement the plants and control algae, but for reasons of minimalism the number of species are often limited.[10]

Iwagumi[]

The Iwagumi style is a specific subtype of the nature style. The Iwagumi (岩組) term itself comes from the Japanese "rock formation" and refers to a layout where stones play a leading role.[11] In the Iwagumi style, each stone has a name and a specific role.[12] Rocks provide the bony structure of the aquascape and the typical geometry employs a design with three main stones, with one larger stone and two other smaller stones, although additional rocks can also be used.[13] The Oyaishi (親石), or main stone, is placed slightly off-center in the tank, and Soeishi (添石), or accompanying stones, are grouped near it, while Fukuseki (副石), or secondary stones, are arranged in subordinate positions.[14] The location of the focal point of the display, determined largely by the asymmetric placement of the Oyaishi, is considered important, and follows ratios that reflect Pythagorean tuning.[15]

Jungle style[]

Some hobbyists also refer to a "jungle" (or "wild jungle") style, separate from either the Dutch or nature styles, and incorporating some of the features of them both. The plants are left to assume a natural, untrimmed look. Jungle style aquascapes usually have little or no visible hardscape material, as well as limited open space. Bold, coarser leaf shapes, such as Echinodorus bleheri, are used to provide a wild, untamed appearance. Unlike nature syle, the jungle style does not follow clean lines, or employ fine textures. A jungle canopy effect can be obtained using combinations of darker substrates, tall plants growing up to the surface, and floating plants that block light, offering a dappled lighting effect. Other plants used in jungle style aquascapes include Microsorum pteropus, Bolbitis heudelotii, Vallisneria americana, Crinum species, Aponogeton species, Echinodorus species, Sagittaria subulata, Hygrophila pinnatifida, Anubias species, and Limnobium laevigatum.[16][17]

Biotopes[]

The styles above often combine plant and animal species based on the desired visual impact, without regard to geographic origin. Biotope aquariums are designed instead to replicate exactly a particular aquatic habitat at a particular geographic location, and not necessarily to provide a gardenlike display. Plants and fish need not be present at all, but if they are, they must match what would be found in nature in the habitat being represented, as must any gravel and hardscape, and even the chemical composition of the water. By including only those organisms that naturally exist together, biotopes can be used to study ecological interactions in a relatively natural setting.[18][19]

Paludariums[]

A paludarium is an aquarium that combines water and land inside the same environment. These designs can represent habitats including tropical rainforests, jungles, riverbanks, bogs, or even the beach.[20] In a paludarium, part of the aquarium is underwater, and part is above water. Substrate is built up so that some "land" regions are raised above the waterline, and the tank is only partially filled with water. This allows plants, such as Cyperus alternifolius and Spathiphyllum wallisii, as well as various Anubias and some bromeliads, to grow emersed, with their roots underwater but their tops in the air, as well as completely submersed. In some configurations, plants that float on the surface of the water, such as Eichhornia crassipes and Pistia stratiotes, can be displayed to full advantage. Unlike other aquarium setups, paludariums are particularly well-suited to keeping amphibians.[21]

Saltwater reefs[]

Dutch and nature style aquascapes are traditionally freshwater systems. In contrast, relatively few ornamental plants can be grown in a saltwater aquarium. Saltwater aquascaping typically centers, instead, on mimicking a reef. An arrangement of live rock forms the main structure of this aquascape, and it is populated by corals and other marine invertebrates as well as coralline algae and macroalgae, which together serve much the same aesthetic role as freshwater plants.[22][23]

Lighting plays a particularly significant role in the reef aquascape. Many corals, as well as tridacnid clams, contain symbiotic fluorescent algae-like dinoflagellates called zooxanthellae.[24] By providing intense lighting supplemented in the ultraviolet wavelengths, reef aquarists not only support the health of these invertebrates, but also elicit particularly bright colors emitted by the fluorescent microorganisms.[25]

Techniques[]

In addition to design, freshwater aquascaping also requires specific methods to maintain healthy plants underwater. Plants are often trimmed to obtain the desired shape, and they can be positioned by tying them in place inconspicuously with thread.[27][28] Most serious aquascapers use aquarium-safe fertilizers, commonly in liquid or tablet form, to help the plants fill out more rapidly.[29] Some aquarium substrates containing laterite also provide nutrients.[30]

It is also necessary to support photosynthesis, by providing light and carbon dioxide. A variety of lighting systems may be used to produce the full spectrum of light, usually at 2–4 watts per gallon (0.5–1 watts per litre).[31] Lights are usually controlled by a timer that allows the plants to be acclimated to a set cycle.[31] Depending on the number of plants and fish, the aquascape may also require carbon dioxide supplementation. This can be accomplished with a simple homemade system, using a soda bottle filled with yeast, warm water, and sugar, and connected to an airstone in the aquarium, or with a pressurized CO2 tank that injects a set amount of carbon dioxide into the aquarium water.[32][33]

Algae (including cyanobacteria, as well as true algae) is considered distracting and unwanted in aquascaping, and is controlled in several ways. One is the use of animals that consume algae, such as some fish (notably cyprinids of the genera Crossocheilus and Gyrinocheilus, and catfish of the genera Ancistrus, Hypostomus, and Otocinclus), shrimp, or snails, to clean the algae that collects on the leaves. A second is using adequate light and CO2 to promote rapid growth of desired plants, while controlling nutrient levels, to ensure that the plants utilize all fertilizer without leaving nutrients to support algae.[34]

Although serious aquascapers often use a considerable amount of equipment to provide lighting, filtration, and CO2 supplementation to the tank, some hobbyists choose instead to maintain plants with a minimum of technology, and some have reported success in producing lush plant growth this way.[35] This approach, sometimes called the "natural planted tank" and popularized by , can include the use of soil in place of aquarium gravel, the elimination of CO2 apparatus and most filtration, and limited lighting. Instead, only a few fish are kept, to limit the quantity of fish waste, and the plants themselves are used to perform the water-cleansing role typically played by aquarium filters, by utilizing what fish waste there is as fertilizer.[36][37]

Contests[]

Early Dutch hobbyists began the practice of aquascape contests, with over 100 local clubs.[8] Judges had to go through about three years of training and pass examinations in multiple disciplines in order to qualify.[8][38] This competition continues to be held every year, under the auspices of the National Aquarium Society.[39] There are three rounds, beginning with contests in local clubs. First-place local winners are entered in the second round, held in fifteen districtkeuring (districts). The winners at that level are then entered in the third round, which is the national championship.[39]

In the Dutch contest, the focus is not only on composition, but also on the biological well-being of the aquarium's inhabitants. Most points are, in fact, awarded for such biological criteria as fish health, plant health, and water quality. Unlike contests in other countries, the judges travel to each contestant's home to evaluate the tank, where they measure the water parameters themselves.[39]

The Aquatic Gardeners Association,[40] based in the United States, Aqua Design Amano,[41] based in Japan, and AquaticScapers Europe,[42] based in Germany, also conduct annual freshwater aquascaping contests. Entries from around the world are submitted as photographs and explanatory text online.[43]

The Aquatic Gardeners Association contest is judged based on:

- overall impression (35 points),

- composition, balance, use of space and use of color (30 points),

- selection and use of materials (20 points), and

- viability of aquascape (15 points).[43]

There are also smaller contests conducted by Acuavida in Spain,[44] by the Greek Aquarist's Board,[45] and by the French association Aquagora.[46]

Public aquariums[]

Large public aquariums sometimes use aquascaping as part of their displays. As early as the 1920s, the New York Aquarium included a moray eel display tank that was decorated with calcareous tufa rock, arranged to resemble a coral reef, and supporting some stony corals and sea fans.[47] Because they typically present wildlife from a particular habitat, modern day displays are often created to be biologically accurate biotopes.[48] The largest aquascape of the Japanese nature aquarium style in a public aquarium is situated in the , Lisbon, Portugal. The temporary exhibit is called "Forests Underwater by Takashi Amano".[49]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Hennig, Matt (June 2003), Amano versus Dutch: Two art forms in profile, Tropical Fish Hobbyist, pp. 68–74.

- ^ Harrison, Tim (3 July 2019). "A Brief And Incomplete History of Aquascaping". Barr Report.

- ^ "Aquascaping 101 – An Introductory Guide for Beginners". FishTankSetups. 16 June 2017. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- ^ James, Barry (1986), A Fishkeeper's Guide to Aquarium Plants, London: Tetra Press/Salamander Books, ISBN 0-86101-207-0

- ^ Mitchell, Sherry (2 October 2003). "The Fish Are Fine, but the Plants Are Fabulous". The Washington Post. Retrieved 27 July 2010.

- ^ Wei, Tan Karr (26 July 2007). "The exotic trade of aquascaping". Malaysia Star. Retrieved 27 July 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Netburn, Deborah (19 September 2009). "Aquascaping: Aquarium meets terrarium in the Japanese-inspired design practice". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 27 July 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Hudson, Robert Paul (30 May 2008), Going Dutch Archived 10 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Axelrod, Herbert R., Warren E. Burgess, Neal Pronek, Glen S. Axelrod and David E. Boruchowitz (1998), Aquarium Fishes of the World, Neptune City, N.J.: T.F.H. Publications, p. 718, ISBN 0-7938-0493-0.

- ^ The Nature Aquarium Style, 8 January 2014.

- ^ "Iwagumi and Sanzon Iwagumi Aquariums," Aquatic Eden website, 11 February 2007.

- ^ "Iwagumi Aquascaping: A Beginner's Guide". The Aquarium Adviser. 16 December 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ The Iwagumi Layout: An Introduction, 7 January 2014

- ^ Amano, Takashi (2009), How to improve your Iwagumi layout, The Aquatic Gardener, vol. 22, number 1, pp. 37–41.

- ^ "The Golden Rule of Aquascaping," Aquatic Eden website, 16 November 2006.

- ^ Farmer, George. "Our guide to aquascaping styles" (PDF). UK Aquatic Plant Society. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 August 2010. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- ^ Terver, Denis (2009). "Définition de aquascaping". Aquaportail (in French). Archived from the original on 22 September 2009. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- ^ James 1986, pp. 37–45.

- ^ "Biotope Aquaria," Mongabay.com, 7 December 2004.

- ^ Paludariums: Discover Water Garden Terrariums!

- ^ Paludariums.net.

- ^ Borneman, Eric H. (2004), Aquarium Corals: Selection, Husbandry, and Natural History, Neptune City, N.J.: T.F.H. Publications, pp. 323–341, ISBN 1-890087-47-5

- ^ Michael, Scott W. (November 2006), Aquascaping reef habitats, Aquarium Fish Magazine, pp. 66–73.

- ^ Borneman 2004, pp. 47–55.

- ^ Borneman 2004, pp. 326–334.

- ^ Alexander, Bob (November 2005). "The first Parlour Aquariums and the Victorian Aquarium Craze". History of parlour aquarium. parlouraquariums.org. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 24 December 2010.

- ^ Amano, Takashi (2008), Nature aquarium techniques to create & maintain an aquascape, The Aquatic Gardener, vol. 21, number 2, pp. 8–17.

- ^ Turon, Lluis Ruscalleda (2009), How to use Riccia and Java moss in the aquarium, The Aquatic Gardener, vol. 22, number 4, pp. 11–13.

- ^ James 1986, p. 16.

- ^ James 1986, p. 28.

- ^ Jump up to: a b James 1986, pp. 20–29.

- ^ James 1986, p. 17.

- ^ Nyberg, Tarah (2003), Yeast CO2 Archived 18 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine, (Retrieved 10 October 2009).

- ^ James 1986, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Lass, David A. (March 2009), Three tough planted tanks, Aquarium Fish International, pp. 30–37.

- ^ Walstad, Diana (2003), Ecology of the planted aquarium: a practical manual and scientific treatise for the home aquarist, 2nd edition, Ashland Ohio: Atlas Books, ISBN 0-9673773-1-5.

- ^ "Online forum on the "Natural" method". Aquaticplantcentral.com. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ^ "Bondskeurmeesters: Judges' website". Cbkm.nl. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "NBAT Dutch contest website". Nbat.nl. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ^ "Aquatic Gardeners Association". Aquatic-gardeners.org. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ^ "Aqua Design Amano". Adana.co.jp. 27 April 2012. Archived from the original on 21 January 2011. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ^ "AquaticScapers Europe". Aquaticscapers.com. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Aquatic Gardeners Association judging website". Showcase.aquatic-gardeners.org. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ^ "Acuavida". Acuavida. Archived from the original on 11 June 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ^ "Greek Aquarist's Board". Aquatek.gr. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ^ "Aquagora CAPA". Aquagora.fr. Archived from the original on 5 May 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ^ Townsend, Charles Haskins (1922, reprinted 2004), The Public Aquarium: Its Construction, Equipment, and Management, Honolulu: University Press of the Pacific, p. 17, ISBN 1-4102-1147-9.

- ^ Buckley, Kate (2010), Planted aquaria for zoological parks, The Aquatic Gardener, vol. 23, number 4, pp. 5–20.

- ^ "Forests Underwater". Oceanário de Lisboa. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

Further reading[]

- Amano, Takashi (1992), Nature Aquarium World, Neptune City, N.J.: T.F.H. Publications, English translation by Christopher Perrius (in one volume), ISBN 0-7938-0089-7.

- Artists Create Mesmerizing Miniature Worlds, All Within The Confines Of A Fish Tank, at the Huffington Post, 4 February 2014 (accessed 17 February 2014). Includes noteworthy photographs of aquascapes.

External links[]

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Hydroculture/Physiology/Aquatic |

The following sites offer tutorials, images, and in-depth discussions on aquascaping styles and techniques:

- Aquatic Gardeners Association

- UK Aquatic Plant Society

- Great Aquascapes Group at Flickr

- Aquatic Eden Website

- Advanced Aquascaping Guide

- Rotala Butterfly – Calculator tools for planted tanks

These sites provide extensive non-commercial descriptions of aquatic plant species and their use in aquascaping:

- Fishkeeping

- Hobbies

- Aquariums

- Visual arts media

- Crafts

- Horticulture and gardening

- Hydroculture

- Types of garden

- Pet equipment