Jeanne Villepreux-Power

Jeanne Villepreux-Power, born Jeanne Villepreux (24 September 1794 – 25 January 1871), was a pioneering French marine biologist who in 1832 was the first person to create aquaria for experimenting with aquatic organisms. The English biologist Richard Owen referred to her as the "Mother of Aquariophily."[1] She was the inventor of the aquarium and the systematic application of the aquarium to study marine life, which is still used today. In her time as a forefront cephalopods researcher, she proved that the argonauta argo produces its own shells, as opposed to acquiring them.[2] Villepreux-Power is also a noted dressmaker,[3] author, and conservationist, as well as the first female member of the Catania Accademia Gioenia.[4]

Early life[]

Villepreux-Power was born in Juillac, Corrèze, on September 24[2] or 25th, 1794,[5] the eldest child of a shoemaker and a seamstress.[2] Living until 18 in the rural countryside of France,[2] not much is known about her early life. She learned to read and write, but not much more.[5]

Moving to Paris[]

At the age of 18, in 1812, she walked to Paris to become a dressmaker, a distance of over 400 kilometres (250 mi). She was accompanied by her cousin to act as her guardian, but he assaulted her and left her to seek refuge in an Orleans police station until she could receive new travel documents.[5]

Due to that delay, her initial opportunity had since been occupied by someone else. She found another opportunity working as a seamstress assistant.[5] She built out and proved her skills many times over, until she became fairly well known.

In 1816, she became well known for creating the wedding gown of Princess Caroline in her wedding to Charles-Ferdinand de Bourbon. She met and married the English merchant, James Power, in 1818 and the couple moved to Sicily and settled in Messina where lived for about 25 years.[6]

Foray into Science[]

It was after moving to Sicily where Jeannette Villepreux-Power took an interest in continuing her education. She began to study geology, archeology, and natural history;[7] in particular she made physical observations and experiments on marine and terrestrial animals. She wanted to inventory the island's ecosystem[6] and did so during frequent walks around the city. As she traveled, she would document and collect samples which were later compiled and published in Itinerario della Sicilia riguardante tutti i rami di storia naturale e parecchi di antichità che essa contiene and Guida per la Sicilia.[5]

Villepreux-Power then began to more intently study cephalopods and other marine life and was in need of a vessel that would allow her better access to observation over time of the same marine animals.[4] While land animals could be observed somewhat easily, marine life was distinctly harder to examine. As such, she worked to develop a glass enclosure, ultimately developing three working models to study live marine life in and out of the water.[8] The first was the aquarium as we know it today; the second glass surrounded by a case that was submerged in the ocean; the third an anchored cage also to be submerged in the ocean for larger marine life like mollusks.[4]

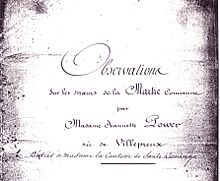

In 1834, a professor, Carmelo Maravigna, wrote in the Giornale Letterario dell’Accademia Gioenia di Catania that Villepreux-Power should be credited with the invention of the aquarium and systematic application of it to the study of marine life.[9] She created three types of aquarium: a glass aquarium for her study, a submersible glass one in a cage, and a cage for larger molluscs that would anchor at sea.[10] Her first book was published in 1839 describing her experiments, called Observations et expériences physiques sur plusieurs animaux marins et terrestres.[10]

Her second book, Guida per la Sicilia, was published in 1842.[10] It has been republished by the Historical Society of Messina.[11] She also studied molluscs and their fossils; in particular she favoured Argonauta argo. At the time, there was uncertainty over whether the Argonaut species produced its own shell, or acquired that of a different organism (similar to hermit crabs). Villepreux-Power's work showed that they do indeed produce their own shells.[6] As a groundbreaking discovery, there was a considerable amount of backlash that she received for her work.[7]

Villepreux-Power was also concerned with conservation, and is credited with developing sustainable aquaculture principles in Sicily.[10] She also helped to found ideas of aquaculture, which is largely considered a more sustainable food source in the future, specifically through utilizing cages attached to the shore containing fish at different lifecycle stages to generate repopulation opportunities that could be moved to underpopulated rivers.[4]

She was the first woman member of the Catania Accademia Gioenia, and a correspondent member of the London Zoological Society and sixteen other learned societies.[12]

Late life[]

Villepreux-Power and her husband left Sicily in 1843, and many of her records and scientific drawings were lost in a shipwreck.[11][10] Although she continued to write, she conducted no further research.[10] She did, however, become a public speaker.[2] She and husband divided their time between Paris and London. She fled Paris during a siege by the Prussian Army in the winter of 1870, returning to Juilliac.[10] She died in January 1871.

In 1997 her name, "Villepreux-Power," was given to a crater on Venus discovered by the Magellan probe.[12]

Reportedly, she also kept two tame beech marten as pets.[citation needed]

Popular culture[]

A biographical song about Jeanne Villepreux is featured on "26 Scientists Volume Two: Newton to Zeno", a 2008 album by the California band Artichoke.[13]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ "Women's History Month: Jeanne Villepreux-Power". 13.7 Billion Years. 14 March 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Jeanne Villepreux-Power: Marine Biologist and Inventor of the Aquarium". interestingengineering.com. 25 September 2018. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ "Rad Women Of History: This 19th Century Marine Biologist Invented The Aquarium". Fatherly. 26 August 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Sandra (19 December 2020). "Jeanne Villepreux-Power - Epigenesys - platform for Health, Medicine & Advisors". Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Jeanne Villepreux-Power". She Thought It. 29 January 2018. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Swaby, Rachel (2015). Headstrong: 52 Women Who Changed Science - And the World. New York: Broadway Books. pp. 51–53. ISBN 9780553446791.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Jeannette Villepreux-Power". oumnh.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ "Jeanne Villepreux-Power | French-born naturalist". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ Arnal, Claude. "Jeannette Villepreux Power a Messine: l'Argonauta argo et l'invention de l'aquarium (1832)" (PDF). Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Potočnik], European Commission, Directorate-General for Research; [forew. Janez (2009). Women in science. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. ISBN 978-92-79-11486-1. Archived from the original on 7 March 2013. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Arnal, Claude. "Jeanne Villepreux-Power: A Pioneering Experimental Malacologist". The Malacological Society of London Bulletin. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Arnal, Claude. "Villepreux-Power, Jeanne". 4000 Years of Women in Science. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ Sellers, Timothy (14 May 2009). "26 Scientists Volume Two: Newton-Zeno". Artichoke. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- 1794 births

- 1871 deaths

- French marine biologists

- French women biologists

- 19th-century French women scientists

- 19th-century French scientists

- French zoologists

- Women inventors