Arirang

| Arirang in North Korea | |

|---|---|

A man about to depart on a journey through a mountain pass is seen off by a woman in a scene from the Arirang Festival in North Korea. | |

| Country | North Korea |

| Reference | 914 |

| Region | Asia and the Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2014 (9th session) |

| Arirang in South Korea | |

|---|---|

Song So-hee performing "Arirang" | |

| Country | South Korea |

| Reference | 445 |

| Region | Asia and the Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2012 (7th session) |

| Arirang | |

| Hangul | 아리랑 |

|---|---|

| IPA | a.ɾi.ɾaŋ |

"Arirang" (아리랑; [a.ɾi.ɾaŋ]) is a Korean folk song that is often considered to be the anthem of Korea.[1] There are about 3,600 variations of 60 different versions of the song, all of which include a refrain similar to, "Arirang, arirang, arariyo (아리랑, 아리랑, 아라리요)"[2] It is estimated the song is more than 600 years old.[3]

"Arirang" is included twice on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage list. South Korea successfully submitted the song for inclusion on the UNESCO list in 2012.[3][2] North Korea also successfully submitted the song for inclusion in 2014.[1][4] In 2015, the South Korean Cultural Heritage Administration added the song to its list of important intangible cultural assets.[5]

The song is sung today in both North and South Korea, a symbol of unity in an otherwise divided region, since the Korean War.

History[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (December 2017) |

Arrange Origin[]

It is believed that "Arirang" originated in Jeongseon, Gangwon Province. "Arirang" as a term today is ambiguous in meaning, but some linguists have hypothesized that "ari" (아리) might have meant "beautiful" in ancient Korean and that "rang" (랑) might have been a way of referring to a "groom."[6] According to a legend, the name is derived from the story of a bachelor and a maiden who fell in love while picking Camellia blossoms near the wharf at Auraji (아우라지) — a body of water which derives its name from the Korean word "eoureojida" (어우러지다) that translates to something close to "be in harmony" or "to meet," like Auraji connects the waters of Pyeongchang and Samcheok to the Han River.[7] There are two versions of this story. In the first one, the bachelor cannot cross the Auraji to meet the maiden because the water is too high and so, they sing a song to express their sorrow. In the second version, the bachelor attempts to cross the Auraji and drowns, singing the sorrowful song after he dies.[8]

Other theories on the origin of the name "Arirang" point to Lady Aryeong, wife of the first king of Silla; "arin," the Jurchen word for "hometown"."[9]

According to Professor Keith Howard, "Arirang" originated in the mountainous regions of Jeongseon and the first mention of the song was found in a 1756 manuscript.[10]

According to Pete Seeger, who sang the song in concert in the 1960s, the song goes back to the 1600s when a despotic emperor was imprisoning people right and left who had opposed him. He hung these prisoners from tall pine trees on top of the hill of Arirang, located outside Seoul. Legend states that one of the prisoners condemned to death, walked his final miles singing of how much he loved his country, and how much he hated to say goodbye to it. It was soon picked up by the other prisoners, where it became a Korean tradition that any man had the right to sing this song before his execution.

First recording[]

The first known recording of "Arirang" was made in 1896 by American ethnologist Alice C. Fletcher. At her home in Washington, D.C., Fletcher recorded three Korean students singing a song she called "Love Song: Ar-ra-rang."[11][12] One source suggests that the students belonged to noble Korean families and were studying abroad at Howard University during the period in which the recording was made. [13] Another source suggests that the singers were Korean workers who happened to be living in America during that time.[14] The recordings are currently housed in the U.S. Library of Congress.[15]

Resistance anthem[]

During the Japanese occupation of Korea from 1910 to 1945, when singing was censored heavily and it became a criminal offense for anyone to be singing any patriotic song including the national anthem of Korea, Arirang became an unofficial anthem. "Arirang" became a resistance anthem against Imperial Japanese rule.[16][17] Korean protesters sang "Arirang" during the March 1 Movement, a Korean demonstration against the Japanese Empire in 1919. Many of the variations of "Arirang" that were written during the occupation contain themes of injustice, the plight of labourers, and guerrilla warfare. It was also sung by the mountain guerrillas who were fighting against the fascists. [16]

The most well-known lyrics to "Arirang" first appeared in the 1926 silent film Arirang, directed by Na Woon-gyu. Arirang is now considered a lost film but various accounts say the film was about a Korean student who became mentally ill after being imprisoned and tortured by the Japanese. The film was a hit upon its release and is considered the first Korean nationalist film.[18][16][19]

Popularity in Japan[]

During the Japanese occupation of Korea, Japan experienced a craze for Korean culture and for "Arirang", in particular. Over 50 Japanese versions of "Arirang" were released between 1931 and 1943, in genres including pop, jazz, and mambo.[16] Some Japanese soldiers were familiar with "Arirang" from their service in Japanese Korea, or from their interactions with forcibly conscripted Korean comfort women, labourers and soldiers.

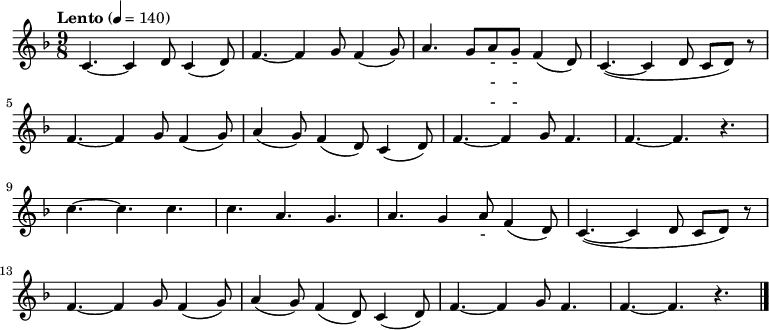

Musical score[]

Lyrics[]

All versions of "Arirang" include a refrain similar to, "Arirang, arirang, arariyo (아리랑, 아리랑, 아라리요)."[2] The word "arirang" itself is nonsensical and does not have a precise meaning in Korean.[20] It is, however, a palindrome in hangul. While the other lyrics vary from version to version, the themes of sorrow, separation, reunion, and love appear in most versions.[4][21]

The table below includes the lyrics of "Standard Arirang" from Seoul. The first two lines are the refrain. The refrain is followed by three verses.

| Hangul/Chosŏn'gŭl | Hanja | Romanization | English translation[21][22] |

|---|---|---|---|

아리랑, 아리랑, 아라리요... |

아리랑, 아리랑, 아라리요... |

Arirang, arirang, arariyo... |

Arirang, arirang, arariyo... |

나를 버리고 가시는 님은 |

나를 버리고 가시는 님은 |

Nareul beorigo gasineun nimeun |

My love, you are leaving me |

청천하늘엔 잔별도 많고, |

晴天下늘엔 잔별도 많고, |

Cheongcheonhaneuren janbyeoldo manko, |

Just as there are many stars in the clear sky, |

저기 저 산이 백두산이라지, |

저기 저 山이 白頭山이라지, |

Jeogi jeo sani baekdusaniraji, |

There, over there, that mountain is Baekdu Mountain, |

Variations[]

There are an estimated 3,600 variations of 60 different versions of "Arirang."[2] Titles of different versions of "Arirang" are usually prefixed by their place of origin.[9]

While "Jeongseon Arirang" is generally considered to be the original version of the song, "Bonjo Arirang" (literally: Standard Arirang) from Seoul is one of the most famous versions. This version was first made popular when it was used as the theme song of the influential 1926 film Arirang.[9]

Other famous variations include "Jindo Arirang" from South Jeolla Province, a region known for being the birthplace of Korean folk music genres pansori and sinawi; and "Miryang Arirang" from South Gyeongsang Province.[23][24]

Official status[]

UNESCO[]

Both South Korea and North Korea submitted "Arirang" to be included on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage list. South Korea successfully submitted the song for inclusion in 2012.[3][2] North Korea successfully submitted the song for inclusion in 2014.[1][4]

South Korea[]

In 2015, the South Korean Cultural Heritage Administration added the "Arirang" to its list of important intangible cultural assets.[5]

U.S. Army[]

The U.S. Army's 7th Infantry Division adopted "Arirang" as its official march song in May 1956, after receiving permission from Syngman Rhee, the first president of South Korea. The division had been stationed in Korea from 1950 to 1953, during the Korean War.[25]

In popular culture[]

This section appears to contain trivial, minor, or unrelated references to popular culture. (October 2018) |

Music[]

- American composer John Barnes Chance based his 1962-63 concert band composition Variations on a Korean Folk Song on a version of "Arirang" that he heard in Korea in the late 1950s.[26]

- In 2007, South Korean vocal group SG Wannabe released the album The Sentimental Chord which contains a song entitled "Arirang". The group is accompanied by Korean traditional instruments and the actual Arirang melody is played by an electric guitar during the bridge prior to the key change.[27][28] They have since performed the song live with the National Traditional Orchestra of Korea and at several Arirang Festivals.

- The New York Philharmonic performed "Arirang" for an encore during its trip to North Korea on February 26, 2008.[29]

- In November 2013, the student choir at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies performed "Arirang" in English, Chinese, Japanese, French, Italian, Spanish, German, Russian, Arabic and Korean.[30]

- The K-Pop group, A.C.E, performed "Jindo Arirang (Prehistory)" for the Revival of Arirang program on Arirang Culture. Their unique version that stayed true to the original song is also included on their new album, Changer: Dear Eris.

Films[]

- Arirang is the title of early Korean filmmaker Na Woon-gyu's influential 1926 film, which popularized the song "Arirang" in the 20th century.[9]

- Arirang is also the title of a 2011 South Korean documentary. The film won the top prize in the Un Certain Regard category at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival.[31]

Media[]

- Arirang TV and Arirang Radio are international English-language media stations run by the Korea International Broadcasting Foundation.[32][33]

Sports[]

- North Korea's mass gymnastics and performance festival is commonly known as the Arirang Festival.[34]

- At the 2000 Summer Olympics opening ceremony in Sydney, Australia, South Korean and North Korean athletes marched into the stadium together carrying the Korean Unification Flag while "Arirang" played.[35]

- South Korean fans used "Arirang" as a cheering song during the 2002 FIFA World Cup.[9]

- South Korean figure skater Yuna Kim performed to "Arirang" during her free skate in the 2011 World Figure Skating Championships, where she placed second.[36]

- Parts of "Arirang" were used many times during the Pyeongchang 2018 Winter Olympics, especially during the Opening Ceremony[37] and in the Olympic Broadcasting Services TV Intro. During the gala show of figure skating, Choi Da-bin skated to "Arirang".

- At the 2018 Asian Games "Arirang" was played when the Korea Unification Team won the gold medal in canoeing.[38]

Video games[]

- Kim Wu's theme in Killer Instinct has elements of "Arirang", sung by Hoona Kim.[39]

- "Arirang" is used as the Korean civilization's theme in Sid Meier's Civilization VI.[40]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "N. Korea's Arirang wins UNESCO intangible heritage status". Yonhap News Agency. November 27, 2014. Archived from the original on December 6, 2017. Retrieved December 5, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Arirang, lyrical folk song in the Republic of Korea". Intangible Cultural Heritage. UNESCO. Retrieved December 5, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Chung, Ah-young (December 12, 2012). "'Arirang' makes it to UNESCO heritage". The Korea Times. Retrieved December 5, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Arirang folk song in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea". Intangible Cultural Heritage. UNESCO. Retrieved December 5, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "'Arirang' Listed as National Intangible Asset". The Chosun Ilbo. July 15, 2015. Retrieved December 5, 2017.

- ^ "Singing". Korean Folk Song, Arirang. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ "Auraji Lake (아우라지) - Sightseeing - Korea travel and tourism information". www.koreatriptips.com. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ The National Folk Museum of Korea (2014). Encyclopedia of Korean Folk Literature. Encyclopedia of Korean Folklore and Traditional Culture Vol. III. 길잡이미디어. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-8928900848.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "From lyrical folk song to cheering song: variations of 'Arirang' in Korean history". The Korea Times. Yonhap News Agency. December 6, 2012. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- ^ Howard, Keith (May 15, 2017). Perspectives on Korean Music: Preserving Korean Music: Intangible Cultural Properties as Icons of Identity. I. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-351-91168-9.

- ^ Yoon, Min-sik (September 27, 2017). "Oldest recorded Arirang to be on display in Seoul". The Korea Herald. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- ^ Kim, Hyeh-won (May 11, 2012). "Arirang under renewed light ahead of UNESCO application". Yonhap News Agency. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- ^ Provine, Robert C. "Alice Fletcher's Notes on the Earliest Recordings of Korean Music" (PDF). The Academy of Korean Studies. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- ^ Maliangkay, Roald (2007). "Their Masters' Voice: Korean Traditional Music SPs (Standard Play Records) under Japanese Colonial Rule". The World of Music. 49 (3): 53–74. ISSN 0043-8774. JSTOR 41699788.

- ^ "Alice C Fletcher collection of Korean cylinder recordings". Library of Congress. 1896. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Atkins, E. Taylor (August 2007). "The Dual Career of "Arirang": The Korean Resistance Anthem That Became a Japanese Pop Hit". The Journal of Asian Studies. 66 (3): 645–687. doi:10.1017/s0021911807000927. hdl:10843/13185. JSTOR 20203201. S2CID 162634680.

- ^ Koehler, Robert (2015). Traditional Music: Sounds in Harmony with Nature. Volume 8 of Korea Essentials. Seoul Selection. ISBN 978-1624120428.

- ^ Edwards, Matthew (2014). Film Out of Bounds: Essays and Interviews on Non-Mainstream Cinema Worldwide. McFarland. p. 198. ISBN 978-1476607801.

- ^ Taylor-Jones, Kate (2017). Divine Work, Japanese Colonial Cinema and its Legacy. Bloomsbury USA. ISBN 978-1501306136.

- ^ "Arirang (아리랑)". Sejong Cultural Society. 2015. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kim Yoon, Keumsil; Williams, Bruce (2015). Two Lenses on the Korean Ethos: Key Cultural Concepts and Their Appearance in Cinema. McFarland. p. 39. ISBN 978-0786496822.

- ^ Damodaran, Ramu (Winter 2017). "UNAI Impacts Scholarship, Research for Greater Good". SangSaeng. APCEIU. 49: 23.

- ^ "Jindo Arirang". Sejong Cultural Society. 2015. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- ^ "Milyang Arirang". Sejong Cultural Society. 2015. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- ^ "Chronological History 7th Infantry Division". 7th Infantry Division Association. May 25, 2012. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- ^ Miles, Richard B; et al. (2010). Teaching Music Through Performing in Band Volume 1. Chicago: GIA Publications, Inc. pp. 590–598.

- ^ "SG워너비, 1년만에 '컴백'...4집 '아리랑' 발표". The Chosun Ilbo (in Korean). March 30, 2007.

- ^ "[안&밖] SG워너비 '국악 접목' 뜻은 좋았지만 …". JoongAng Ilbo (in Korean). May 21, 2007.

- ^ Wakin, Daniel J. (February 27, 2008). "North Koreans Welcome Symphonic Diplomacy". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- ^ Lee, Claire (November 19, 2013). "HUFS to hold concert featuring 'Arirang' in 10 languages". The Korea Herald. Retrieved December 8, 2017.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (June 7, 2012). "Arirang – review". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved December 8, 2017.

- ^ "Arirang TV begins DTV service in metropolitan Washington, D.C., area". The Korea Times. Yonhap News Agency. April 28, 2011. Retrieved December 8, 2017.

- ^ "Arirang Radio to Go On Air in U.S." The Chosun Ilbo. January 11, 2012. Retrieved December 8, 2017.

- ^ DeHart, Jonathan (July 29, 2013). "Pyongyang's Arirang Festival: Eye Candy for the Masses". The Diplomat. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- ^ Ito, Makoto (September 16, 2000). "Two Koreas make history during opening ceremony". The Japan Times Online. ISSN 0447-5763. Retrieved December 8, 2017.

- ^ Hersh, Philip (April 30, 2011). "Botched jumps cost Kim world title, Czisny the bronze". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- ^ "Do passado ao futuro cerimonia de abertura de pyeongchang projeta futuro de crianças (In Portuguese)". Sport TV. February 9, 2018. Archived from the original on February 27, 2018. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- ^ AS, Diario (August 27, 2018). "Unified Korea dragon boat team win historic gold at Asian Games". AS.com. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- ^ Celldweller & Atlas Plug (March 10, 2016), Killer Instinct Season 3 - Creating The Music for "Kim Wu", retrieved February 8, 2020

- ^ "Geoff Knorr's Facebook Page". Facebook. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity

- Korean traditional music

- Korean-language songs

- National symbols of Korea

- South Korean folk songs

- South Korea national football team songs

- Korean traditions

- Important Intangible Cultural Properties of South Korea