Asbury Park, New Jersey

Asbury Park, New Jersey | |

|---|---|

| City of Asbury Park | |

| Nickname(s): | |

From Left: Asbury Park Convention Hall (image courtesy of Dave Frey), Main Street, Tillie, Cookman Ave, Old Heating Plant, Philadelphia Toboggan Company Carousel | |

| |

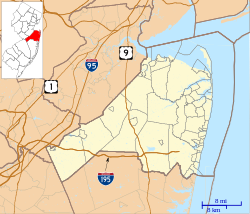

Asbury Park Location in Monmouth County | |

| Coordinates: 40°13′22″N 74°00′37″W / 40.222884°N 74.010232°WCoordinates: 40°13′22″N 74°00′37″W / 40.222884°N 74.010232°W[3][4] | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Monmouth |

| Incorporated | March 26, 1874 (as borough) |

| Reincorporated | February 28, 1893 (as city) |

| Named for | Francis Asbury |

| Government | |

| • Type | Faulkner Act (council–manager) |

| • Body | City Council |

| ��� Mayor | John B. Moor (term ends December 31, 2022)[5][6][7] |

| • Manager | Donna Vieiro (interim)[8] |

| • Municipal clerk | Cindy A. Dye[9][10] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1.61 sq mi (4.17 km2) |

| • Land | 1.43 sq mi (3.70 km2) |

| • Water | 0.18 sq mi (0.47 km2) 11.18% |

| Area rank | 439th of 565 in state 36th of 53 in county[3] |

| Elevation | 16 ft (5 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 16,116 |

| • Estimate (2019)[16] | 15,408 |

| • Rank | 158th of 566 in state 14th of 53 in county[17] |

| • Density | 11,319.5/sq mi (4,370.5/km2) |

| • Density rank | 24th of 566 in state 1st of 53 in county[17] |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (Eastern (EDT)) |

| ZIP Code | |

| Area code(s) | 732[20] |

| FIPS code | 3402501960[3][21][22] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0885141[3][23] |

| Website | www |

Asbury Park (/æzbɛriː/) is a beachfront city in Monmouth County, New Jersey, United States, located on the Jersey Shore and part of the New York City Metropolitan Area.[24]

As of the 2010 United States Census, the city's population was 16,116,[13][14][15] reflecting a decline of 814 (−4.8%) from the 16,930 counted in the 2000 Census, which had in turn increased by 131 (+0.8%) from the 16,799 counted in the 1990 Census.[26]

It was ranked the sixth-best beach in New Jersey in the 2008 Top 10 Beaches Contest sponsored by the New Jersey Marine Sciences Consortium.[27]

Asbury Park was originally incorporated as a borough by an act of the New Jersey Legislature on March 26, 1874, from portions of Ocean Township. The borough was reincorporated on February 28, 1893. Asbury Park was incorporated as a city, its current type of government, as of March 25, 1897.[28]

History[]

Early years[]

A seaside community, Asbury Park is located on New Jersey's central coast. Developed in 1871 as a residential resort by New York brush manufacturer James A. Bradley, the city was named for Francis Asbury, the first American bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States.[29][30][31] The founding of Ocean Grove in 1869, a Methodist camp meeting to the south, encouraged the development of Asbury Park and led to its being a "dry town."

Bradley was active in the development of much of the city's infrastructure, and despite his preference for gas light, he allowed the Atlantic Coast Electric Company (precursor to today's Jersey Central Power & Light Co.) to offer electric service.[32] Along the waterfront, Bradley installed the Asbury Park Boardwalk, an orchestra pavilion, public changing rooms, and a pier at the south end of that boardwalk. Such success attracted other businessmen. In 1888, Ernest Schnitzler built the Palace Merry-Go-Round on the southwest corner of Lake Avenue and Kingsley Street, the cornerstone of what would become the Palace Amusements complex; other attractions followed.[33]

During these early decades in Asbury Park, a number of grand hotels were built, including the Plaza Hotel.[35]

Uriah White, an Asbury Park pioneer, installed the first artesian well water system.[36] As many as 600,000 people a year vacationed in Asbury Park during the summer season in the early years, riding the New York and Long Branch Railroad from New York City and Philadelphia to enjoy the mile-and-a-quarter stretch of oceanfront Asbury Park.[36] By 1912, The New York Times estimated that the summer population could reach 200,000.[37]

The country by the sea destination experienced several key periods of popularity. The first notable era was the 1890s, marked by a housing growth, examples of which can still be found today in a full range of Victorian architecture. Coinciding with the nationwide trend in retail shopping, Asbury Park's downtown flourished during this period and well into the 20th century.

1920s and modern development[]

1920s[]

The 1920s saw a dramatic change in the boardwalk with the construction of the Paramount Theatre and Convention Hall complex, the Casino Arena and Carousel House, and two handsome red-brick pavilions. Beaux Arts architect Warren Whitney of New York was the designer. He had also been hired to design the imposing Berkeley-Carteret Hotel positioned diagonally across from the theater and hall. At the same time, Asbury Park launched a first-class education and athletic program with the construction of a state-of-the-art high school overlooking Deal Lake.

1930s[]

On September 8, 1934, the wreck of the ocean liner SS Morro Castle, which caught fire and burned, beached itself near the city just yards away from the Asbury Park Convention Hall; the city capitalized on the event, turning the wreck into a tourist attraction.[38]

In 1935, the newly founded Securities and Exchange Commission called Asbury Park's Mayor Clarence F. Hetrick to testify about $6 million in "beach improvement bonds" that had gone into default. At the same time, the SEC also inquired about rental rates on the beach front and why the mayor reduced the lease of a bathhouse from $85,000 to $40,000, among many other discrepancies that could have offset debt.[39] The interests of Asbury Park's bond investors led Senator Frank Durand (Monmouth County) to add a last-minute "Beach Commission" amendment to a municipal debt bill in the New Jersey legislature. When the bill became law, it ceded control of the Asbury Park beach to Governor Harold Hoffman and a governor's commission.[40][41] The city of Asbury Park sued to restore control of the beach to the municipal council, but the New Jersey Court of Errors and Appeals (until 1947, the state's highest court) upheld the validity of the law in 1937.[42] When Durand pressed New Jersey's legislature to extend the state's control of Asbury Park's beach in 1938, the lower house staged a walk out and the Senate soon adjourned, a disruption that also prevented a vote for funding New Jersey's participation in the 1939 New York World's Fair.[43][44] In December 1938, the court returned control of the beach to the municipal council under the proviso that a bond repayment agreement was created; Asbury Park was the only beach in New Jersey affected by the Beach Commission law.[45]

1940s[]

In 1943, the New York Yankees held their spring training in Asbury Park instead of Florida.[46] This was because rail transport had to be conserved during the war, and Major League Baseball's Spring Training was limited to an area east of the Mississippi River and north of the Ohio River.[47]

With the opening of the Garden State Parkway in 1947, Asbury Park saw the travel market change as fewer vacationers took trains to the seashore. While the Asbury Park exit on the Parkway opened in 1956 and provided a means for drivers to reach Asbury Park more easily, additional exits further south allowed drivers access to new alternative vacation destinations, particularly on Long Beach Island.[48]:71–72

1950s and beyond[]

In the decades that followed the war, surrounding farm communities gave way to tracts of suburban houses, encouraging the city's middle-class blacks as well as whites to move into newer houses with spacious yards.[48]:190

With the above-mentioned change in the travel market, prompted by the opening of the Garden State Parkway in 1947 and the opening of Monmouth Mall 10 miles (16 km) away in Eatontown in 1960, Asbury Park's downtown became less of an attraction to shoppers. Office parks built outside the city resulted in the relocation of accountants, dentists, doctors, lawyers, and other professionals. Moreover, the opening of Great Adventure (on July 1, 1974), a combination theme park and drive-through safari located on a lake in Jackson Township—and close to a New Jersey Turnpike exit—proved to be stiff competition for a mile-long stretch of aging boardwalk amusements.[49]

Riots that broke out in the city on July 4, 1970, resulted in the destruction of aging buildings along Springwood Avenue, one of three main east–west corridors into Asbury Park and the central shopping and entertainment district for those living in the city's southwest quadrant.[50] Many of those city blocks have yet to be redeveloped into the 21st century.[citation needed]

Although it was placed on the National Register of Historic Places,[51] Palace Amusements was closed in 1988 and was demolished in 2004 despite attempts to save it.[52] The complex had featured the famous face of Tillie, a symbol of the Jersey Shore.[52]

In 1990, the famous carousel at the Casino Pier was sold to Family Kingdom Amusement Park in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, where it continues to operate.[53]

21st century[]

From 2002 onward, the rest of Asbury Park has been in the midst of a cultural, political, and economic revival, including a burgeoning industry of local and national artists.[citation needed] Its dilapidated downtown district is undergoing revitalization while most of the nearly empty blocks that overlook the beach and boardwalk are slated for massive reconstruction. In 2005, the Casino's walkway reopened, as did many of the boardwalk pavilions.[54]

In 2007, the eastern portion of the Casino building was demolished. There are plans to rebuild this portion to look much like the original; however, the interior will be dramatically different and may include a public market (as opposed to previously being an arena and skating rink). There has also been more of a resurgence of the downtown as well as the boardwalk, with the grand reopening of the historic Steinbach department store building, as well as the rehabilitation of Convention Hall and the Fifth Avenue Pavilion (previously home to one of the last remaining Howard Johnson's restaurants). The historic Berkeley-Carteret Hotel, which is to be restored to four-star resort status, was acquired in 2007; the first residents moving into the newly constructed condominiums known as North Beach, the rehabilitation of Ocean Avenue, and the opening of national businesses on Asbury Avenue.

After Hurricane Sandy, Asbury Park was one of the few communities on the Jersey Shore to reopen successfully for the 2013 summer season. Most of the boardwalk had not been badly damaged by the massive hurricane. On Memorial Day Weekend 2013, Governor Chris Christie and President Barack Obama participated in an official ceremony before a crowd of 4,000, marking the reopening of Asbury Park and other parts of the Jersey Shore. The "Stronger Than The Storm" motto was emphasized at this ceremony.[55][56]

LGBTQIA+ community[]

Since the 1950s at least, Asbury Park has had a growing LGBT community. After property values plummeted locally in Asbury Park, gays from New York City purchased and restored Victorian homes, leading to a rejuvenation of parts of the city.[57] In 1999, dance music pioneer Shep Pettibone opened Paradise, a gay discotheque near the ocean. He has since also opened the Empress Hotel, the state's only gay-oriented hotel. Another notable establishment is Georgies (formerly the Fifth Avenue Tavern). Every summer the Jersey Gay Pride parade draws hundreds of thousands of people to this LGBT destination.

In 2021, the LGBTQ+ community center QSpot relocated to Asbury Park.[58]

Geography[]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city had a total area of 1.61 square miles (4.17 km2), including 1.43 square miles (3.70 km2) of land and 0.18 square miles (0.47 km2) of water (11.18%).[3][4]

Unincorporated communities, localities and place names located partially or completely within the city include North Asbury and Whitesville (located along the city's border with Neptune Township).[59]

The city borders the Monmouth County communities of Interlaken, Loch Arbour, Neptune Township, and Ocean Township.[60][61][62]

Deal Lake covers 158 acres (64 ha) and is overseen by the Deal Lake Commission, which was established in 1974. Seven municipalities border the lake, accounting for 27 miles (43 km) of shoreline, also including Allenhurst, Deal, Interlaken, Loch Arbour, Neptune Township and Ocean Township.[63]

Demographics[]

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1900 | 4,148 | — | |

| 1910 | 11,150 | 168.8% | |

| 1920 | 13,400 | 20.2% | |

| 1930 | 14,981 | 11.8% | |

| 1940 | 14,617 | −2.4% | |

| 1950 | 17,094 | 16.9% | |

| 1960 | 17,366 | 1.6% | |

| 1970 | 16,533 | −4.8% | |

| 1980 | 17,015 | 2.9% | |

| 1990 | 16,799 | −1.3% | |

| 2000 | 16,930 | 0.8% | |

| 2010 | 16,116 | −4.8% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 15,408 | [16][64][65] | −4.4% |

| Population sources: 1900-1920[66] 1900–1910[67] 1900–1930[68] 1930-1990[69] 2000[70][71] 2010[13][14][15] | |||

2010 Census[]

The 2010 United States census counted 16,116 people, 6,725 households, and 3,174 families in the city. The population density was 11,319.5 per square mile (4,370.5/km2). There were 8,076 housing units at an average density of 5,672.4 per square mile (2,190.1/km2). The racial makeup was 36.45% (5,875) White, 51.35% (8,275) Black or African American, 0.49% (79) Native American, 0.48% (77) Asian, 0.12% (20) Pacific Islander, 7.64% (1,232) from other races, and 3.46% (558) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 25.53% (4,115) of the population.[13]

Of the 6,725 households, 24.1% had children under the age of 18; 18.2% were married couples living together; 23.1% had a female householder with no husband present and 52.8% were non-families. Of all households, 42.1% were made up of individuals and 13.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.35 and the average family size was 3.33.[13]

23.8% of the population were under the age of 18, 10.7% from 18 to 24, 30.7% from 25 to 44, 24.5% from 45 to 64, and 10.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34.0 years. For every 100 females, the population had 95.2 males. For every 100 females ages 18 and older there were 95.9 males.[13]

The Census Bureau's 2006–2010 American Community Survey showed that (in 2010 inflation-adjusted dollars) median household income was $33,527 (with a margin of error of +/− $2,802) and the median family income was $27,907 (+/− $5,012). Males had a median income of $34,735 (+/− $3,323) versus $33,988 (+/− $4,355) for females. The per capita income for the borough was $20,368 (+/− $1,878). About 31.1% of families and 29.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 44.9% of those under age 18 and 26.0% of those age 65 or over.[72]

2000 Census[]

As of the 2000 United States Census[21] there were 16,930 people, 6,754 households, and 3,586 families residing in the city. The population density was 14,290.0 per square mile (5,629.4/km2) making it Monmouth County's most densely populated municipality. There were 7,744 housing units at an average density of 5,416.7 per square mile (2,090.9/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 15.77% White, 67.11% Black, 0.32% Native American, 0.70% Asian, 0.07% Pacific Islander, 6.49% from other races, and 5.53% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 18.58% of the population.[70][71]

There were 6,754 households, out of which 31.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 20.2% were married couples living together, 26.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 46.9% were non-families. 39.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 15.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.46 and the average family size was 3.36.[70][71]

In the city the population was spread out, with 30.1% under the age of 18, 10.6% from 18 to 24, 29.8% from 25 to 44, 18.3% from 45 to 64, and 11.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 31 years. For every 100 females, there were 88.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 83.2 males.[70][71]

The median income for a household in the city was $23,081, and the median income for a family was $26,370. Males had a median income of $27,081 versus $24,666 for females. The per capita income for the city was $13,516. About 29.3% of families and 40.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 46.5% of those under age 18 and 37.1% of those age 65 or over.[70][71]

Economy[]

Urban Enterprise Zone[]

Portions of the city are part of a joint Urban Enterprise Zone (UEZ) with Long Branch, one of 32 zones covering 37 municipalities statewide. The city was selected in 1994 as one of a group of 10 zones added to participate in the program.[73] In addition to other benefits to encourage employment and investment within the UEZ, shoppers can take advantage of a reduced 3.3125% sales tax rate (half of the 6+5⁄8% rate charged statewide) at eligible merchants.[74] Established in September 1994, the city's Urban Enterprise Zone status expires in September 2025.[75]

Hotels[]

At one time, there were many hotels along the beachfront. Many were demolished after years of sitting vacant, although the Sixth Avenue House Bed & Breakfast Hotel (formerly Berea Manor) was recently restored after being abandoned in the 1970s—it is no longer operational and was sold as a single family home. Hotels like the Berkeley and Oceanic Inn have operated concurrently for decades, while the Empress Hotel and Hotel Tides were recently restored and reopened. The Asbury Hotel, located on 5th Avenue, was the first hotel to be "built" in Asbury Park in 50+ years. It stands where the old Salvation Army building once stood, which has sat vacant for over a decade. The building itself was not torn down, but the entire inside was gutted and redone. Glass paneling was added to the front and all the original outside brickwork was kept. While located a block and a half from the beach, a great view of the ocean is still offered by the upper floors and rooftop.

Currently open hotels include the Berkeley Oceanfront Hotel (formerly the Berkeley-Carteret Oceanfront Hotel), The Empress Hotel, Hotel Tides, Asbury Park Inn, Oceanic Inn, Mikell's Big House Bed & Breakfast as well as The Asbury Hotel[76] and The Asbury Ocean Club Hotel,[77] both developed by iStar, the master developer for the Asbury Park Waterfront.

Demolished:

- The Albion Hotel (2001)[78]

- The Metropolitan Hotel (2007)[79]

Media[]

Local media includes:

- The Asbury Park Press

- The award-winning weekly newspaper The Coaster has covered local news in Asbury Park since it was founded in 1983.

- The Asbury Park Sun

- The owner of TriCity News, a weekly news and art publication for Monmouth County, chose Asbury Park for its headquarters.[80]

Arts and culture[]

Music scene[]

The Asbury Park music scene gained prominence in the 1960s with bands such as the Jaywalkers and many others, who combined rock and roll, rhythm and blues, soul and doo-wop to create what became known as the Sound of Asbury Park (S.O.A.P.). On December 9, 2006, founding members of S.O.A.P. reunited for the "Creators of S.O.A.P.: Live, Raw, and Unplugged" concert at The Stone Pony and to witness the dedication of a S.O.A.P. plaque on the boardwalk outside of Convention Hall. The original plaque included the names Johnny Shaw, Billy Ryan, Bruce Springsteen, Garry Tallent, Steve Van Zandt, Mickey Holiday, "Stormin'" Norman Seldin, Vini "Mad Dog" Lopez, Fast Eddie "Doc Holiday" Wohanka, Billy "Cherry Bomb" Lucia, Clarence Clemons, Nicky Addeo, Donnie Lowell, Jim "Jack Valentine" Cattanach, Ken "Popeye" Pentifallo, Jay Pilling, John "Cos" Consoli, Gary "A" Arntz, Larry "The Great" Gadsby, Steve "Mole" Wells, Ray Dahrouge, Johnny "A" Arntz, David Sancious, Margaret Potter, Tom Potter, Sonny Kenn, Tom Wuorio, Rick DeSarno, Southside Johnny Lyon, Leon Trent, Buzzy Lubinsky, Danny Federici, Bill Chinnock, Patsy Siciliano, and Sam Siciliano. An additional plaque was added on August 29, 2008, honoring John Luraschi, Carl "Tinker" West, George Theiss, Vinnie Roslin, Mike Totaro, Lenny Welch, Steve Lusardi, and Johnny Petillo.[81]

Musicians and bands with strong ties to Asbury Park, many of whom frequently played clubs there on their way to fame, include Fury of Five, The Gaslight Anthem, Clarence Clemons, the E Street Band, Jon Bon Jovi and Bon Jovi, Southside Johnny and the Asbury Jukes, Patti Smith, Arthur Pryor, Count Basie, The Clash, U.S. Chaos, Johnny Thunders, The Ramones, The Exploited, Charged GBH, Marty Munsch, Gary U.S. Bonds, along with many more.

In 1973 Bruce Springsteen released his debut album Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. On his follow-up album, The Wild, the Innocent and the E Street Shuffle, one of the songs is entitled "4th of July, Asbury Park (Sandy)". Several books chronicle the early years of Springsteen's career in Asbury Park. Daniel Wolff's 4 July Asbury Park examines the social, political and cultural history of the city with a special emphasis on the part that music played in the city's development, culminating in Springsteen's music. Beyond the Palace by Gary Wien is a comprehensive look at the local music scene that Springsteen emerged from, and includes many photographs of musicians and clubs. Against the backdrop of the fading resort, Alex Austin's novel The Red Album of Asbury Park tracks a young rock musician pursuing his dream in the late 60s/early 70s, with Springsteen as a potent but as yet unknown rival.[82]

A B&W multi-camera recording of Blondie in 1979, just prior to the release of their fourth album, Eat to the Beat, was taped at the Asbury Park Convention Hall on July 7, a home-state crowd for Jersey girl Debbie Harry, who was raised in Hawthorne.[83]

New Jersey Music Hall of Fame[]

The New Jersey Music Hall of Fame was founded in Asbury Park in 2005. There have been plans to build a music museum somewhere in the city as part of the redevelopment.[84]

Asbury hip-hop and other music[]

The West Side of Asbury Park has traditionally been home to music, including jazz, soul, gospel, doo wop, and R&B. African American artists such as the Jersey Shore's own Count Basie as well as Duke Ellington, Lenny Welch, the Broadways, Josephine Baker, Bobby Thomas, Clarence Clemons and others "either played or were inspired by the afro-centered Springwood Avenue club circuit on the West Side of Asbury Park" in the mid-century period.[85]

The Asbury Park Music Foundation, working with Lakehouse Music Academy and the Boys & Girls Club of Monmouth County, founded the Hip Hop Institute to teach music and life skills education relevant to young hip hop enthusiasts.

The Asbury Park Museum hosts an exhibit on the history of music on the West Side, spanning the decades from 1880 to 1980.[86]

Live music and arts venues[]

Asbury Park is considered a destination for musicians, particularly a subgenre of rock and roll known as the Jersey Shore sound, which is infused with R&B. It is home to venues including:

- The Stone Pony, founded in 1974, a starting point for many performers.

- Across town, on Fourth Avenue, is Asbury Lanes, a recently reopened functioning bowling alley and bar with live performances ranging from musical acts (formerly with a heavy focus on punk music), neo-Burlesque, hot rod, and art shows. The reopened venue's latest focused has been mostly on indie rock and pop.

- The Saint, on Main Street (formerly the Clover Club), which brings original, live music to the Jersey Shore.

- Convention Hall holds larger events.

- The Paramount Theatre is adjacent to Convention Hall.

- The Wonder Bar.

- The Asbury Park Brewery on Sewell Avenue hosts small shows with a capacity of 150 and a brewery inside the venue.[87]

- The Empress Hotel is an LGBT resort owned by music producer Shep Pettibone that features Paradise Nightclub.

- The Baronet, a vintage movie theater which dates back to Buster Keaton's era, was near Asbury Lanes, but its roof recently caved in and the building was demolished. The Asbury Hotel pays homage to this once great theater with its 5th floor rooftop movie theater called "The Baronet". The Asbury Hotel also has an 8th floor rooftop bar, paying homage to the former building inhabitants and calling it "Salvation."

In a town that was once nearly abandoned, there are now over 60 restaurants, bars, coffee houses, two breweries, a coffee roastery, and live music venues situated in Asbury Park's boardwalk and downtown districts.

Festivals and other recurring arts events[]

- The Asbury Park Music + Film Festival (APMFF). This event is held annually in the spring.[88]

- Asbury Park Music Foundation is a non-profit organization that offers live music throughout the year including the free summer concert series Music Mondays in Springwood Park, AP Live and the Asbury Park Concert Band on the boardwalk. Ticketed events including Sundays on St. John's, A Very Asbury Holiday Show! at the Paramount Theater, Sunday Sessions are held throughout the year to benefit the music foundation's mission to provide music education programs, scholarships, instruments to the underserved youth in the community as well as supporting established and emerging local musicians with opportunities to perform.[89]

- The Asbury Park Surf Music Festival, held on the boardwalk in August, celebrates surf music .[90]

- The Asbury Music Awards. Formerly known as the Golden T-Bird Awards, these were established in 1993 by Scott Stamper and Pete Mantas to recognize and support significant contributions and achievements of local and regional participants in the music industry. The name of the awards was changed to the Asbury Music Awards in 1995. The award ceremony is held in November of each year, most recently at the Stone Pony.[91]

- The Sea.Hear.Now Festival is a surfing and music festival that first appeared on the beach in Asbury Park in September 2018, as a celebration of live music, art, ocean sustainability, and surf culture. Digital pop culture magazine "The Pop Break" named Sea.Hear.Now the best new music festival of the year in 2018.[92][93]

- Music Mondays at Springwood Park. These are weekly live music events held at Springwood Park in the summer months. Hosted by the Asbury Park Music Foundation.[94]

- The Wave Gathering Music Festival. This festival was established in 2006. The festival is held during the summer. Businesses across Asbury Park offer food, drink, art, music, crafts, and their stages for performances. Stages are also set up in parks, on the boardwalk, and in other open spaces. The event takes place over several days.[95]

- First Saturdays. Popular with numerous Asbury Park residents and visitors is the monthly First Saturday event. On the first Saturday of every month, Asbury Park's downtown art galleries, home design studios, restaurants, antique shops, and clothing boutiques remain open throughout the evening, serving hors d'oeuvres and offering entertainment, to showcase the city's residential and commercial resurgence.[96]

- The Asbury Park Tattoo Convention, also known as the Visionary Tattoo Festival, is held every July.[97]

- The Garden State Film Festival. In 2003, actor Robert Pastorelli founded the Garden State Film Festival, which draws over 30,000 visitors to Asbury Park each spring for a four-day event including screenings of 150 features, documentaries, shorts and videos, concerts, lectures and workshops for filmmakers. In 2012, a film industry exposition will be held for the first time in Convention Hall during the Festival.[98]

- The Bamboozle Music Festival. This was first held in Asbury Park in 2003, 2004, and 2005.[99] The festival returned to its original location for the ten-year anniversary in 2012, headlined by My Chemical Romance, Foo Fighters, and Bon Jovi, drawing over 90,000 people to the city over the three-day span in which it was held.[100]

- The Asbury Park Women's Convention is held each winter.

Murals and other public art[]

Noted muralists and other local artists have installed various murals along the Asbury Park boardwalk and the cityscape in recent years. The 2016 Wooden Walls Mural Project began in July of that year and reimagined the Sunset Pavilion building with around a dozen new murals.[101][102]

Other arts and entertainment[]

On October 5, 2013, the largest gathering of zombies was achieved by the 9,592 participants in New Jersey Zombie Walk at the Asbury Park Boardwalk, an event held in Asbury Park every October.[103]

Surfing and other sports[]

Every winter, when the surf grows colder and rougher than in the summer, the city is home to the Cold War, an annual cold water surfing battle.

In 1943, the New York Yankees held spring training in Asbury Park to comply with restrictions on rail travel during World War II.[104]

Asbury Park is the nominal home to Asbury Park F.C., described as "Asbury Park's most storied sports franchise and New Jersey's second-best football club." The project is a parody of a modern pro soccer team born out of a joke between social media professional and soccer tastemaker Shawn Francis and his friend Ian Perkins, guitarist with The Gaslight Anthem. Despite never playing games the club has an extensive merchandise line available online, including new and retro replica jerseys.[105]

Parks and recreation[]

Parks include:[106]

- Springwood Park. Springwood Park is a park[107] established in 2016 near the Asbury Park train station, adjacent to the Second Baptist Church of Asbury Park, a historically African-American congregation founded in 1885.[108] It is across from Kula Urban Farm and Kula Cafe, an urban farm and small restaurant that grows produce for local restaurants.[109] Springwood Park is home to Music Mondays, weekly live-music outdoor events in the summer months that are hosted by the Asbury Park Music Foundation.[94] The park is also home to political and/or civil rights rallies from time to time.[110]

- Wheeler Park

Government[]

Local government[]

The City of Asbury Park is governed within the Faulkner Act, formally known as the Optional Municipal Charter Law, under the Council-Manager form of government. The city was previously governed under the 1923 Municipal Manager Law form of New Jersey municipal government until voters approved the Council-Manager form in 2013.[111] The government is comprised of a five-member City Council with a directly elected mayor and four council positions all elected at-large in non-partisan elections, to serve four-year terms of office on a staggered basis in elections held in even years as part of the November general election.[6][111]

The form of government was chosen based on the final report issued in August 2013 by a Charter Study Commission that had narrowed its options to the weak Mayor Council-Manager form or the strong Mayor Faulkner Act form, ultimately choosing to recommend the Council-Manager form as it would retain desired aspects of the 1923 Municipal Manager Law (non-partisan voting for an at-large council with a professional manager) while allowing a directly elected mayor, elections in November and grants voters the right to use initiative and referendum.[112] The four winning council candidates in the November 2014 general election drew straws, with two being chosen to serve full four-year terms and two serving for two years. Thereafter, two council seats will be up for election every two years.[113]

As of 2020, members of the Asbury Park City Council are Mayor John Moor (term of office ends December 31, 2022), Deputy Mayor Amy Quinn (2020), Eileen Chapman (2020), Barbara "Yvonne" Clayton (2020) and Jesse Kendle (2022).[5][6][114][115][116][117]

In May 2016, the City Council appointed Eileen Chapman to fill the vacant council seat expiring in December 2016 that had been held by Joe Woerner until he resigned from office.[118]

Myra Campbell, the last mayor under the old form of government, was the first African-American woman to be chosen as mayor when she took office in July 2013.[119]

Fire Department[]

| Operational area | |

|---|---|

| State | New Jersey |

| City | Asbury Park |

| Address | 800 Main Street |

| Agency overview | |

| Established | 1887 |

| Annual calls | ~7,647 (2018) |

| Employees | ~54 |

| EMS level | BLS Transport |

| IAFF | L384 |

| Facilities and equipment | |

| Stations | 1 |

| Engines | 3 (including spare) |

| Trucks | 2 (including spare) |

| Rescues | 1 |

| Ambulances | 3 (including spare) |

| Fireboats | 1 |

| Website | |

| http://www.cityofasburypark.com/APFD | |

Beyond providing emergency services, the Asbury Park Fire Department works to prevent future fires and accidents. Department responsibilities range from fire code enforcement, arson investigations, and fire prevention activities to fire and life safety education programs for children, families, and seniors.

Asbury Park currently has a centrally located fire station (with a new one planned for the future), with one Engine Company, one Ladder Company, two Basic Life Support Ambulances, a fireboat, and a Duty Battalion Chief. The department's apparatus fleet includes 3 Engines (including spare), 2 Ladder Trucks (including spare), 1 Rescue Truck, and 2 Ambulances, in addition to other equipment. The Asbury Park Fire Department employs 56 people, of which, 54 are certified Firefighter/Emergency Medical Technicians.[120]

Federal, state, and county representation[]

Asbury Park is located in the 6th Congressional district[121] and is part of New Jersey's 11th state legislative district.[14][122][123]

For the 117th United States Congress, New Jersey's Sixth Congressional District is represented by Frank Pallone (D, Long Branch).[124][125] New Jersey is represented in the United States Senate by Democrats Cory Booker (Newark, term ends 2027)[126] and Bob Menendez (Harrison, term ends 2025).[127][128]

For the 2018–2019 session (Senate, General Assembly), the 11th Legislative District of the New Jersey Legislature is represented in the State Senate by Vin Gopal (D, Long Branch) and in the General Assembly by Joann Downey (D, Freehold Township) and Eric Houghtaling (D, Neptune Township).[129][130]

Monmouth County is governed by a Board of Chosen Freeholders consisting of five members who are elected at-large to serve three year terms of office on a staggered basis, with either one or two seats up for election each year as part of the November general election. At an annual reorganization meeting held in the beginning of January, the board selects one of its members to serve as Director and another as Deputy Director.[131] As of 2020, Monmouth County's Freeholders are Freeholder Director Thomas A. Arnone (R, Neptune City, term as freeholder ends December 31, 2022; term as freeholder director ends 2021),[132] Freeholder Deputy Director Susan M. Kiley (R, Hazlet Township, term as freeholder ends December 31, 2021; term as deputy freeholder director ends 2021),[133] Lillian G. Burry (R, Colts Neck Township, 2020),[134] Nick DiRocco (R, Wall Township, 2022),[135] and Patrick G. Impreveduto (R, Holmdel Township, 2020)[136].

Constitutional officers elected on a countywide basis are County clerk Christine Giordano Hanlon (R, 2020; Ocean Township),[137][138] Sheriff Shaun Golden (R, 2022; Howell Township),[139][140] and Surrogate Rosemarie D. Peters (R, 2021; Middletown Township).[141][142]

Politics[]

As of March 23, 2011, there were a total of 7,404 registered voters in Asbury Park, of which 2,723 (36.8%) were registered as Democrats, 464 (6.3%) were registered as Republicans and 4,209 (56.8%) were registered as Unaffiliated. There were 8 voters registered to other parties.[143]

In the 2012 presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama received 89.1% of the vote (4,317 cast), ahead of Republican Mitt Romney with 9.9% (480 votes), and other candidates with 1.0% (49 votes), among the 4,896 ballots cast by the city's 8,486 registered voters (50 ballots were spoiled), for a turnout of 57.7%.[144][145] In the 2008 presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama received 87.4% of the vote (4,693 cast), ahead of Republican John McCain with 9.7% (522 votes) and other candidates with 0.5% (28 votes), among the 5,372 ballots cast by the city's 8,429 registered voters, for a turnout of 63.7%.[146] In the 2004 presidential election, Democrat John Kerry received 81.9% of the vote (3,659 ballots cast), outpolling Republican George W. Bush with 17.0% (759 votes) and other candidates with 0.3% (28 votes), among the 4,466 ballots cast by the city's 8,255 registered voters, for a turnout percentage of 54.1.[147]

In the 2013 gubernatorial election, Democrat Barbara Buono received 67.5% of the vote (1,488 cast), ahead of Republican Chris Christie with 30.9% (682 votes), and other candidates with 1.6% (36 votes), among the 2,287 ballots cast by the city's 8,819 registered voters (81 ballots were spoiled), for a turnout of 25.9%.[148][149] In the 2009 gubernatorial election, Democrat Jon Corzine received 75.1% of the vote (1,728 ballots cast), ahead of Republican Chris Christie with 19.1% (440 votes), Independent Chris Daggett with 4.3% (100 votes) and other candidates with 0.4% (9 votes), among the 2,301 ballots cast by the city's 7,692 registered voters, yielding a 29.9% turnout.[150]

Historic district[]

Asbury Park Commercial Historic District | |

U.S. National Register of Historic Places | |

U.S. Historic district | |

New Jersey Register of Historic Places

| |

| Location | Roughly bounded by 500, 600, 700 blocks of Cookman and Mattison Avenues and Bond Streets between Lake and Bangs Avenues |

|---|---|

| NRHP reference No. | 14000536[151] |

| NJRHP No. | 3992[152] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | September 30, 2014 |

| Designated NJRHP | July 10, 2014 |

The Asbury Park Commercial Historic District is a historic district located along Cookman and Mattison Avenues and Bond Streets between Lake and Bangs Avenues. The district was added to the National Register of Historic Places on September 30, 2014, for its significance in commerce and entertainment.[153]

Education[]

Public schools[]

The Asbury Park Public Schools serve students in pre-kindergarten through twelfth grade.[154] The district is one of 31 former Abbott districts statewide,[155] which are now referred to as "SDA Districts" based on the requirement for the state to cover all costs for school building and renovation projects in these districts under the supervision of the New Jersey Schools Development Authority.[156][157]

Students from Allenhurst attend the district's schools as part of a sending/receiving relationship.[158] In July 2014, the New Jersey Department of Education approved a request by Interlaken under which it would end its sending relationship with the Asbury Park district and begin sending its students to the West Long Branch Public Schools through eighth grade and then onto Shore Regional High School.[159] Students from Deal had attended the district's high school as part of a sending/receiving relationship that was terminated and replaced with an agreement with Shore Regional.[160]

As of the 2017–18 school year, the district, comprised of five schools, had an enrollment of 2,204 students and 211.5 classroom teachers (on an FTE basis), for a student–teacher ratio of 10.4:1.[161] Schools in the district (with 2017-18 enrollment data from the National Center for Education Statistics[162]) are Bradley Elementary School[163] (427 students; in grades PreK-5), Thurgood Marshall Elementary School[164] (440; PreK-5), Barack Obama Elementary School[165] (362; PreK-5), Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School[166] (349; 6-8) and Asbury Park High School[167] (415; 9-12).[168][169]

In March 2011, the state monitor overseeing the district's finances ordered that Barack Obama Elementary School be closed after the end of the 2010–11 school year, citing a 35% decline in enrollment in the district during the prior 10 years. Students currently attending the school would be reallocated to the district's two other elementary schools, with those going into fifth grade assigned to attend middle school.[170] During the summer of 2012, the school board approved funding for development plans to house the Board of Education in the vacant Barack Obama Elementary School. The school board awarded $894,000 to an architect firm to handle the renovation design and subsequent project bids. The estimated cost of the renovation was $1.6 million.[171]

In 2006, Asbury Park's Board of Education was affected by the city's decision to redevelop waterfront property with eminent domain. In the case Asbury Park Board of Education v. City of Asbury Park and Asbury Partners, LLC, the New Jersey Superior Court, Appellate Division affirmed a ruling in favor of eminent domain of the Board of Education building on Lake Avenue.[172] The Board of Education moved to the third and fourth floors of 603 Mattison Avenue, the former Asbury Park Press building, where it paid $189,327 in rent per year.[171]

In February 2007, the offices of the Asbury Park Board of Education were raided by investigators from the State Attorney General's office, prompted by allegations of corruption and misuse of funds.[173]

Per-student expenditures in Asbury Park have generated statewide controversy for several years. In 2006, The New York Times reported that Asbury Park "spends more than $18,000 per student each year, the highest amount in the state."[174] In both 2010 and 2011, the Asbury Park K-12 school district had the highest per-student expenditure in the state.[175] As of the 2010 school reports, the high school has not met goals mandated by the No Child Left Behind Act and has been classified as "In Need of Improvement" for six years.[176]

Charter schools[]

The Hope Academy Charter School, founded in 2001, is an alternative public school choice that serves students in kindergarten through eighth grade. Admission is based on a lottery of submitted applications, with priority given to Asbury Park residents and siblings of existing students.[177]

Students from Asbury Park in ninth through twelfth grades may also attend Academy Charter High School, located in Lake Como, which also serves residents of Allenhurst, Avon-by-the-Sea, Belmar, Bradley Beach, Deal, Interlaken and Lake Como, and accepts students on a lottery basis.[178]

Crime[]

While 8 of the 17 murders in Monmouth County in 2006 took place in Asbury Park, and 7 of the county's 14 murders in 2007, by 2008 there was only one murder in Asbury Park and five in the whole county. The city's police had added 19 officers since 2003 and expanded its street crime unit. After a spike in gang violence, violent crime had decreased by almost 20% from 2006 to 2008.[179]

In the calendar year through August 26, 2013, Asbury Park has had 6 homicides; there have also been 17 people non-fatally injured in shooting incidents.[180]

In February 2014, "Operation Dead End" arrested gang members of the Crips and Bloods; one Asbury Park patrol officer was arrested for aiding gang members.[181]

On June 16, 2015, Asbury Park police officers arrested a Neptune Township off-duty police officer for the murder of his ex-wife on an Asbury Park street in broad daylight.[182]

| Year | Crime Index Total | Violent crime | Non-violent Crime |

Crime rate Per 1000 |

Violent crime Rate per 1000 |

Non-violent crime Rate per 1000 |

Murder | Rape | Robbery | Aggravated Assault |

Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | 1740 | 386 | 1354 | 103.6 | 23.0 | 80.6 | 2 | 20 | 175 | 189 | [183] |

| 1995 | 1461 | 290 | 1171 | 93.6 | 18.6 | 75.0 | 2 | 11 | 147 | 130 | [183] |

| 1996 | 1590 | 305 | 1285 | 101.9 | 19.5 | 82.3 | 2 | 23 | 139 | 141 | [184] |

| 1997 | 1525 | 357 | 1168 | 89.1 | 20.8 | 68.2 | 1 | 11 | 190 | 155 | [184] |

| 1998 | 1240 | 251 | 989 | 72.4 | 14.7 | 57.8 | 0 | 16 | 116 | 119 | [185] |

| 1999 | 1183 | 302 | 881 | 69.4 | 17.7 | 51.7 | 3 | 16 | 139 | 144 | [185] |

| 2000 | 1224 | 337 | 887 | 72.3 | 19.9 | 52.4 | 1 | 13 | 161 | 162 | [186] |

| 2001 | 1431 | 398 | 1033 | 84.5 | 23.5 | 61.0 | 5 | 14 | 184 | 195 | [186] |

| 2002 | 1260 | 347 | 913 | 74.4 | 20.5 | 53.9 | 3 | 9 | 172 | 163 | [187] |

| 2003 | 1293 | 378 | 915 | 77.0 | 22.5 | 54.5 | 2 | 7 | 183 | 186 | [187] |

| 2004 | 1429 | 360 | 1069 | 85.6 | 21.6 | 64.0 | 3 | 5 | 196 | 156 | [188] |

| 2005 | 1313 | 346 | 967 | 78.1 | 20.6 | 57.5 | 3 | 10 | 148 | 185 | [189] |

| 2006 | 1305 | 387 | 918 | 78.5 | 23.3 | 55.2 | 8 | 7 | 194 | 178 | [189] |

| 2007 | 1070 | 351 | 719 | 64.7 | 21.2 | 43.5 | 6 | 11 | 184 | 150 | [190] |

| 2008 | 1265 | 319 | 946 | 76.3 | 19.2 | 57.1 | 1 | 6 | 153 | 159 | [190] |

| 2009 | 1370 | 353 | 1017 | 82.8 | 21.3 | 61.5 | 2 | 6 | 178 | 167 | [191] |

| 2010 | 1491 | 344 | 1147 | 92.5 | 21.3 | 71.2 | 3 | 13 | 188 | 140 | [191] |

| 2011 | 1540 | 260 | 1280 | 95.6 | 16.1 | 79.4 | 4 | 11 | 114 | 131 | [192] |

| 2012 | 1252 | 247 | 1005 | 78.9 | 15.6 | 63.3 | 3 | 10 | 84 | 150 | [193] |

| 2013 | 1106 | 264 | 842 | 69.7 | 16.6 | 53.1 | 6 | 9 | 126 | 123 | [194] |

As of 2013, the Asbury Park Police Department has 88 police employees: 74 men, 10 women, and 4 civilian.[194]

Public health[]

Nearby hospitals include Jersey Shore University Medical Center and Monmouth Medical Center.

From before 1990 to 2015, there were 904 reported cases of HIV/AIDS in Asbury Park. Additionally, there were 418 AIDS-related deaths and 73 deaths of people who had HIV (without AIDS diagnosis.) In 2014, there were nine new cases and 2015, eight.[195] To help people living with AIDS and their caregivers, a not-for-profit foundation called The Center provides assistance with meals, housing, and transportation.[196]

In 2012, Asbury Park reported 6 cases of syphilis, 59 cases of gonorrhea, and 139 cases of chlamydia.[197]

Transportation[]

Roads and highways[]

As of May 2010, the city had a total of 36.20 miles (58.26 km) of roadways, of which 33.78 miles (54.36 km) were maintained by the municipality, 0.92 miles (1.48 km) by Monmouth County and 1.50 miles (2.41 km) by the New Jersey Department of Transportation.[198]

The main access road is Route 71 which runs north–south. Other roads that are accessible in neighboring communities include Route 18, Route 33, Route 35 and Route 66. The Garden State Parkway is at least 15 minutes away via either Routes 33 or 66.

Public transportation[]

NJ Transit offers rail service from the Asbury Park station.[199] on the North Jersey Coast Line, offering service to Newark Penn Station, Secaucus Junction, New York Penn Station and Hoboken Terminal.[200]

NJ Transit bus routes include the 317 to and from Philadelphia, and local service on the 830, 832, 836 and 837 routes.[201] The "Shore Points" route of Academy Bus Lines provides service between Asbury Park and New York City on a limited schedule.[202]

Bike[]

In August 2017, a multi-station bike share program opened in cooperation with Zagster. With six stations in the city, the program is the first of its kind on the Jersey Shore.[203][204][205]

Climate[]

According to the Köppen climate classification system, Asbury Park has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa). Cfa climates are characterized by all months having an average temperature > 32.0 °F (0.0 °C), at least four months with an average temperature ≥ 50.0 °F (10.0 °C), at least one month with an average temperature ≥ 71.6 °F (22.0 °C) and no significant precipitation difference between seasons. Although most summer days are slightly humid with a cooling afternoon sea breeze in Asbury Park, episodes of heat and high humidity can occur with heat index values > 103 °F (39 °C). Since 1981, the highest air temperature was 100.3 °F (37.9 °C) on August 9, 2001, and the highest daily average mean dew point was 77.4 °F (25.2 °C) on August 13, 2016. July is the peak in thunderstorm activity and the average wettest month is August. Since 1981, the wettest calendar day was 5.58 inches (142 mm) on August 27, 2011. During the winter months, the average annual extreme minimum air temperature is 3.6 °F (−15.8 °C).[206] Since 1981, the coldest air temperature was −5.7 °F (−20.9 °C) on January 22, 1984. Episodes of extreme cold and wind can occur with wind chill values < −6 °F (−21 °C). The average seasonal (Nov-Apr) snowfall total is between 18 inches (46 cm) and 24 inches (61 cm), and the average snowiest month is February which corresponds with the annual peak in nor'easter activity.

| hideClimate data for Asbury Park, 1981-2010 normals, extremes 1981-2019 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 71.4 (21.9) |

78.8 (26.0) |

82.1 (27.8) |

88.5 (31.4) |

94.9 (34.9) |

96.8 (36.0) |

99.9 (37.7) |

100.3 (37.9) |

97.5 (36.4) |

93.9 (34.4) |

80.4 (26.9) |

75.0 (23.9) |

100.3 (37.9) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 40.0 (4.4) |

42.6 (5.9) |

49.1 (9.5) |

58.8 (14.9) |

68.2 (20.1) |

77.4 (25.2) |

82.8 (28.2) |

81.6 (27.6) |

75.5 (24.2) |

65.1 (18.4) |

55.2 (12.9) |

45.2 (7.3) |

61.9 (16.6) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 32.4 (0.2) |

34.7 (1.5) |

40.9 (4.9) |

50.4 (10.2) |

59.9 (15.5) |

69.4 (20.8) |

74.9 (23.8) |

73.8 (23.2) |

67.3 (19.6) |

56.4 (13.6) |

47.3 (8.5) |

37.7 (3.2) |

53.8 (12.1) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 24.8 (−4.0) |

26.8 (−2.9) |

32.7 (0.4) |

41.9 (5.5) |

51.5 (10.8) |

61.3 (16.3) |

67.1 (19.5) |

66.1 (18.9) |

59.2 (15.1) |

47.6 (8.7) |

39.3 (4.1) |

30.1 (−1.1) |

45.8 (7.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −5.7 (−20.9) |

1.0 (−17.2) |

6.0 (−14.4) |

18.3 (−7.6) |

35.4 (1.9) |

44.8 (7.1) |

48.7 (9.3) |

45.6 (7.6) |

39.3 (4.1) |

26.5 (−3.1) |

15.0 (−9.4) |

−0.3 (−17.9) |

−5.7 (−20.9) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.62 (92) |

3.07 (78) |

3.93 (100) |

4.15 (105) |

3.81 (97) |

3.60 (91) |

4.69 (119) |

4.72 (120) |

3.62 (92) |

3.94 (100) |

3.85 (98) |

4.02 (102) |

47.02 (1,194) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 64.9 | 61.7 | 60.5 | 61.6 | 65.7 | 70.3 | 69.9 | 71.2 | 71.6 | 69.4 | 67.3 | 65.0 | 66.6 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 21.9 (−5.6) |

22.9 (−5.1) |

28.3 (−2.1) |

37.7 (3.2) |

48.4 (9.1) |

59.3 (15.2) |

64.4 (18.0) |

63.9 (17.7) |

57.8 (14.3) |

46.5 (8.1) |

37.0 (2.8) |

27.0 (−2.8) |

43.0 (6.1) |

| Source: PRISM[207] | |||||||||||||

| hideClimate data for Sandy Hook, NJ Ocean Water Temperature (17 N Asbury Park) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 37 (3) |

36 (2) |

40 (4) |

46 (8) |

55 (13) |

62 (17) |

69 (21) |

72 (22) |

68 (20) |

59 (15) |

51 (11) |

43 (6) |

53 (12) |

| Source: NOAA[208] | |||||||||||||

Ecology[]

According to the A. W. Kuchler U.S. potential natural vegetation types, Asbury Park would have a dominant vegetation type of Appalachian Oak (104) with a dominant vegetation form of Eastern Hardwood Forest (25).[209] The plant hardiness zone is 7a with an average annual extreme minimum air temperature of 3.6 °F (−15.8 °C).[206] The average date of first spring leaf-out is March 24[210] and fall color typically peaks in early-November.

Notable people[]

People who were born in, residents of, or otherwise closely associated with Asbury Park include:

- Bud Abbott (1895–1974), straight man for comedy team of Abbott and Costello, born in Asbury Park.[48]

- Soren Sorensen Adams (1879–1963), inventor and manufacturer of novelty products, including the joy buzzer.[211]

- Stewart H. Appleby (1890–1964), represented New Jersey's 3rd congressional district from 1925 to 1927.[212]

- T. Frank Appleby (1864–1924), represented New Jersey's 3rd congressional district in the United States House of Representatives from 1921 to 1923, and was mayor of Asbury Park from 1908 to 1912.[213]

- Dave Aron (born 1964), recording engineer, live and studio mixer, record producer and musician.[214]

- Nicole Atkins (born 1978), singer-songwriter on Columbia Records.[215]

- Ronald S. Baron (born 1943), mutual fund manager and investor.[216]

- Frederick Bayer (1921–2007), marine biologist who served as curator of the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History.[217]

- Wilda Bennett (1894-1967), actress.[218]

- Richard Biegenwald (1940-2008), serial killer who killed at least nine people, and he is suspected in at least two other murders.[219]

- Scott "Bam Bam" Bigelow (1961–2007), professional wrestler.[220]

- Elizabeth Ann Blaesing (1919-2005), daughter of Warren G. Harding, the 29th President of the United States, and his mistress, Nan Britton.[221]

- Daniel Boyarin (born 1946), historian of religion who is Professor of Talmudic Culture at University of California, Berkeley.[222]

- James A. Bradley (1830-1921), financier and real estate developer who founded the city and served as its mayor.[223]

- Charles H. Brower (1901-1984), advertising executive, copywriter and author.[224]

- Ernest "Boom" Carter, drummer who has toured and recorded with, among others, Bruce Springsteen, with whom he played the drums on the song "Born to Run".[225]

- Marie Castello (1915–2008), longtime boardwalk fortuneteller known as Madam Marie.[226]

- Edna Woolman Chase (1877–1957), editor in chief of Vogue magazine from 1914 to 1952.[227]

- James M. Coleman (1924-2014), politician who served in the New Jersey General Assembly and as a judge in New Jersey Superior Court.[228]

- Stephen Crane (1871–1900), author of The Red Badge of Courage.[229]

- Cookie Cuccurullo (1918-1983), MLB pitcher who played for the Pittsburgh Pirates from 1943 to 1945.[230]

- Danny DeVito (born 1944), actor.[231]

- Les Dugan (1921–2002), American football coach who was the first head football coach at Buffalo State College, serving from 1981 to 1985.[232]

- Cari Fletcher (born 1994), actress, singer, and songwriter.[233]

- Tim Hauser (born 1941), member of The Manhattan Transfer.[234]

- Leon Hess (1914–1999), oil magnate and founder of the Hess Corporation, began his business in the city.[235]

- Robert Hess (1932-1994), scholar of African history who served as the sixth President of Brooklyn College.[236]

- Joey Janela (born 1989), professional wrestler.[citation needed]

- Richard Jarecki (1931-2018), physician who won more than $1 million from a string of European casinos after cracking a pattern in roulette wheels.[237]

- Lou Liberatore (born 1959), actor, has a second home in Asbury Park.[238]

- Robert Melee (born 1966), artist.[239]

- Arthur Pryor (1870–1942), bandleader.[240][241]

- Nazreon Reid (born 1999), power forward for the LSU Tigers basketball team.[242]

- Richie Rosenberg, trombonist who performed with Southside Johnny & The Asbury Jukes.[243]

- Charles J. Ross (1859–1918), vaudeville performer.[244]

- David Sancious (born 1953), early member of the E Street Band.[245]

- Arthur Siegel (1923–1994), songwriter.[246]

- Thomas S. Smith (1917–2002), former mayor of Asbury Park who served in the New Jersey General Assembly.[247]

- Bruce Springsteen (born 1949), singer-songwriter known for his album Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J..[248]

- Lenny Welch (born 1940), pop singer.[249]

- Margaret Widdemer (1884–1976) Pulitzer Prize-winning poet.[250]

- Wendy Williams (born 1964), talk show host and New York Times bestselling author, born in Asbury Park.[251]

- Arthur Augustus Zimmerman (1869–1936), the first world cycling champion, grew up here and owned a hotel after retiring from racing.[252]

In popular culture[]

Palace Amusements and the Tillie mural have featured in numerous works of popular culture. Additional works reference Asbury Park, specifically.

For example, in the song "At Long Last Love" (1938), originally written by Cole Porter for the musical You Never Know (1938), Frank Sinatra sings "Is it Granada I see, or only Asbury Park?"[253]

Bruce Springsteen named his first album "Greetings From Asbury Park, N.J." in 1973 and described his early life there. The artist has also dedicated many songs to Asbury Park such as "4th of July, Asbury Park (Sandy)" and "My City of Ruins" on his 2002 album, "The Rising".[254]

The group mewithoutYou references Asbury Park several times on their album Ten Stories (2012). The song "Bear's Vision of St. Agnes" mentions "that tattered rag shop back in Asbury Park", and the song "Fox's Dream of the Log Flume" mentions the pier and sand dunes.[citation needed]

Asbury Park was used for the location filming of the crime drama City by the Sea (2002), starring Robert De Niro, James Franco and Frances McDormand, which was nominally set in Long Beach, New York, where no filming actually took place, according to a disclaimer that was included as part of the closing credits. The film features scenes set on a shabby, dilapidated boardwalk and in a ruined/abandoned casino/arcade building. Residents of both places objected to the way their cities were depicted.[255] Asbury Park appears at the start of the 1999 film Dogma.

The 2006 horror film Dark Ride is set in Asbury Park.[256]

The Season 2 finale of The Sopranos, "Funhouse", originally aired in April 2000, includes several discrete dream sequences dreamed by Tony that take place on the Asbury Park Boardwalk, including Madame Marie's as well as Tony and Pauly playing cards at a table in the empty hall of the Convention Center. The episode's title alludes to the Palace, which is also shown.[257]

In a 1955 episode of The Honeymooners ("Better Living Though TV"), Alice Kramden ridicules husband Ralph Kramden's seemingly never-ending parade of failed get-rich-quick schemes, including his investment in "the uranium field in Asbury Park".[258]

See also[]

- SS Asbury Park, a coastal steamship that operated between the northern New Jersey shore and New York City from 1904 to 1918

- Asbury Park station, the NJ Transit station that connects Asbury Park to New York City, Bay Head and Newark Airport

References[]

- ^ "New brewery ready to be trendsetter in Asbury Park". nj.com. January 7, 2016. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- ^ Annual ArtsCAP Event Features Author Hisani Dubose, Atlantic Highlands Herald, June 16, 2010. "...Celebrate ArtsCAP's accomplishments in promoting the arts in Asbury Park and ... help plan further blossoming of art and culture in Dark City."

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f 2019 Census Gazetteer Files: New Jersey Places, United States Census Bureau. Accessed July 1, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990, United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mayor & Council, Asbury Park, New Jersey. Accessed March 17, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Spoto, MaryAnn. "Asbury Park gets new mayor, council after voters approve new government", NJ Advance Media for NJ.com, January 1, 2015. Accessed April 20, 2015.

- ^ 2020 New Jersey Mayors Directory, New Jersey Department of Community Affairs. Accessed February 1, 2020.

- ^ City Manager, Asbury Park, New Jersey. Accessed March 17, 2020.

- ^ Stine, Don. "Asbury Park's New City Clerk Begins Post", The Coaster, May 7, 2015. Accessed October 13, 2015. "Asbury Park's new city clerk took over her job this week and said she feels up to the challenge. Cindy A. Dye, who left her job as clerk for North Hanover, began her new job on May 1 and said she is 'glad and excited' to be in the city."

- ^ City Clerk, Asbury Park, New Jersey. Accessed March 17, 2020.

- ^ 2012 New Jersey Legislative District Data Book, Rutgers University Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, March 2013, p. 58.

- ^ "City of Asbury Park". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f DP-1 - Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 for Asbury Park city, Monmouth County, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed February 9, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Municipalities Sorted by 2011-2020 Legislative District, New Jersey Department of State. Accessed February 1, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Table DP-1. Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2010 for Asbury Park city Archived October 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed February 9, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b monmouthcountynewjersey, NJ/PST045218 QuickFacts for Asbury Park city, New Jersey; Monmouth County, New Jersey; New Jersey from Population estimates, July 1, 2019, (V2019), United States Census Bureau. Accessed May 21, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b GCT-PH1 Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density: 2010 - State -- County Subdivision from the 2010 Census Summary File 1 for New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed December 11, 2012.

- ^ Look Up a ZIP Code for Asbury Park, NJ, United States Postal Service. Accessed August 31, 2011.

- ^ ZIP Codes, State of New Jersey. Accessed August 23, 2013.

- ^ Area Code Lookup - NPA NXX for Asbury Park, NJ, Area-Codes.com. Accessed September 17, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b U.S. Census website, United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- ^ Geographic Codes Lookup for New Jersey Archived June 4, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Missouri Census Data Center. Accessed May 20, 2012.

- ^ US Board on Geographic Names, United States Geological Survey. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- ^ Makris, Molly Vollman; Gatta, Mary (2020). Gentrification Down the Shore. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-1-9788-1363-2.

- ^ Henry, McBride, Florine Stettheimer, The Museum of Modern Art 1946.

- ^ Table 7. Population for the Counties and Municipalities in New Jersey: 1990, 2000 and 2010, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development, February 2011. Accessed July 18, 2012.

- ^ Urgo, Jacqueline L. "Sandy laurels for South Jersey; Seven of the Top 10 N.J. beaches are in Cape May County", The Philadelphia Inquirer, May 23, 2008. Accessed July 18, 2012. "Neighboring Wildwood Crest came in second, followed by Ocean City, North Wildwood, Cape May, Asbury Park in Monmouth County, Avalon, Point Pleasant Beach in northern Ocean County, Beach Haven in southern Ocean County and Stone Harbor."

- ^ Snyder, John P. The Story of New Jersey's Civil Boundaries: 1606–1968, Bureau of Geology and Topography; Trenton, New Jersey; 1969. p. 177. Accessed February 9, 2012.

- ^ Cullinane, Bob. "A tale of two towns: One Asbury not like the other", Asbury Park Press, July 31, 2002. Accessed August 23, 2013. "Further reducing the degrees of separation between the two Asburys, Horner said he believed both towns were named after Francis Asbury, the first bishop of the American Methodist church."

- ^ Gannett, Henry. The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States, p. 29. United States Government Printing Office, 1905. Accessed August 27, 2015.

- ^ Hutchinson, Viola L. The Origin of New Jersey Place Names, New Jersey Public Library Commission, May 1945. Accessed August 27, 2015.

- ^ Pike, Helen-Chantal (2005). Asbury Park's Glory Days: The Story of an American Resort. Rutgers University Press, pp 8 ISBN 0-8135-3547-6

- ^ 1888 Palace Amusements Online Museum. Accessed 2007-08-17.

- ^ https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/726531

- ^ "Asbury Park, NJ". Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved August 18, 2007.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) Side O'Lamb: Urban Exploration of the Jersey Shore. Accessed August 17, 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pike, Helen-Chantal (1997,2003). Images of America: Asbury Park., Arcadia Publishing, p 13. ISBN 0-7524-0538-1. Accessed August 23, 2013.

- ^ Staff. "Asbury Park.; Popular Jersey Shore Resort Rapidly Filling with Visitors.", The New York Times, June 9, 2012. Accessed August 23, 2013. "Asbury Park is undergoing its annual transformation from a quiet Winter community of 10,000 inhabitants into a lively metropolitan Summer city with a changing population that sometimes exceeds 200,000 persons."

- ^ Staff. "Asbury to Claim Morro Castle as Museum; Sightseeing Fees Bring $2,800 in a Day", The New York Times, September 11, 1934. Accessed August 4, 2012. "The great hulk of the wrecked Morro Castle has proved to be such a good thing for Asbury Park business that the city authorities decided today to attempt to make the fire-blackened vessel a permanent addition to the beach attractions."

- ^ Staff. "Asbury Park Debt Linked To Politics; Costly Temporary Financing Tied to Boardwalk and Rental 'Iniquities.' Mayor Hetrick On Stand He Tells SEC of $6,000,000, Mostly in Default -- High Interest Rate Defended.", The New York Times, October 26, 1935. Accessed September 17, 2013.

- ^ Staff. "Asbury Park To Sue For Beach Control; Writ to Be Applied For Today to Prevent Commission Taking Jurisdiction.", The New York Times, June 22, 1936. Accessed September 17, 2013.

- ^ Staff. "Asbury Wins Stay On Beach Control; Jurisdiction of Board Named by Hoffman Held Up Pending Ruling on New Law.", The New York Times, June 24, 1936. Accessed September 17, 2013.

- ^ Staff. "Beach Control Act For Asbury Upheld; Jersey High Court Sustains the Validity of the Law Curbing the City's Authority", The New York Times, September 23, 1937. Accessed September 17, 2013.

- ^ Staff. "Jersey Assembly Stages 'Walkout'; Rebels at Upper House's Tactics--Senate Also Adjourns", The New York Times, June 9, 1938. Accessed September 17, 2013.

- ^ Staff. "World's Fair Fund Loses In Jersey; Last-Minute Dispute Before Legislative Recess Leaves $150,000 Unappropriated Veto' Session Thursday Lawmakers to Meet Then to Act on Bills Disapproved by Governor Moore", The New York Times, June 10, 1938. Accessed September 17, 2013.

- ^ Staff. "Asbury Park Freed Of Fiscal Control; State's Commission Had Been in Charge Two Years", The New York Times, December 11, 1938. Accessed September 17, 2013.

- ^ Staff. "Spring Baseball Training Brings Visitors To Asbury Park—Poconos Events; Asbury Park's Season", The New York Times, March 28, 1943. Accessed August 4, 2012. "Asbury Park, N.J.—Spring training of the New York Yankees baseball team has quickened the arrival of visitors this year, many of them bent on watching the conditioning of professional athletes north of the Mason–Dixon Line."

- ^ Suehsdorf, A. D. (1978). The Great American Baseball Scrapbook, p. 103. Random House. ISBN 0-394-50253-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Pike, Helen-Chantal. "Asbury Park's Glory Days – The Story Of An American Resort", Gameroom magazine reviewed by Tim Ferrante. Accessed June 18, 2007. "I didn't know Bud Abbott was born there. It was also the home town of then hair stylist Danny DeVito (yes, there is a photo of the famed actor in his family's shop!) and the childhood stomping ground of Jack Nicholson."

- ^ Pike, Helen-Chantal. Asbury Park's Glory Days: The Story of an American Resort, p. 81. Rutgers University Press, 2007. ISBN 0813540879, 9780813540870. Accessed January 23, 2018.

- ^ Cheslow, Jerry. "If You're Thinking of Living In/Asbury Park; After Bleak Years, Signs of Progress", The New York Times, July 27, 2003. Accessed July 18, 2012. "By the mid-1960s, urban flight began; and on July 4, 1970, race riots gutted much of the city, sealing its fate as a backwater."

- ^ New Jersey, Monmouth County, National Register of Historic Places. Accessed July 18, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b The Aftermath, Palace Amusements Online Museum. Accessed November 10, 2014.

- ^ Staff. "Casino Pier", UltimateRollerCoaster.com, July 26, 2008. Accessed July 18, 2012. "Built in 1923, the Family Kingdom Carousel continues to delight thousands each year. Built by the Philadelphia Toboggan Company, the ride was brought to Myrtle Beach in 1992 from the famed 'Casino' in Asbury Park, New Jersey."

- ^ Schlegel, Jeff. "The Boardwalks of Jersey", The Washington Post, August 10, 2005. Accessed July 18, 2012. "In 2004, the mile-long boardwalk was rebuilt. This year the Casino walkway connecting Asbury Park's boardwalk with neighboring Ocean Grove was reopened."

- ^ Jump up to: a b Robbins, Christopher. "Christie celebrates Asbury Park's successes at boardwalk ribbon-cutting", NJ.com, May 23, 2014. Accessed June 15, 2014.

- ^ Flumenbaum, Martha. "Greetings From Asbury Park, N.J.: Seven Months of Hurricane Sandy Heroes", Huffington Post, May 28, 2013. Accessed June 15, 2014. "Standing on the beach in Asbury Park with 'Born To Run' and 'Who Says You Can't Go Home?' playing in the background, the smell of the ocean and cheesesteaks in the air, surrounded by miniature golf, salt water taffy, and a few feet away from The Stone Pony (where Bruce Springsteen and Jon Bon Jovi got their starts) I watched Governor Chris Christie introduce President Barack Obama to a crowd of about 4,000 today."

- ^ Kuhr, Fred. "There goes the gayborhood: the urban renewal of Asbury Park, N.J., renews the debate: can gay men and lesbians single-handedly transform bad neighborhoods?", The Advocate, July 6, 2004. Accessed June 2, 2011.

- ^ https://www.app.com/story/life/2021/06/07/qspot-lgbt-community-center-asbury-park-nj/7530771002/

- ^ Locality Search, State of New Jersey. Accessed December 18, 2020.

- ^ Areas touching Asbury Park, MapIt. Accessed March 17, 2020.

- ^ Regional Location Map, Monmouth County, New Jersey. Accessed March 17, 2020.

- ^ New Jersey Municipal Boundaries, New Jersey Department of Transportation. Accessed November 15, 2019.

- ^ Home Page, Deal Lake Commission. Accessed July 8, 2015. "The Deal Lake Commission was created by the seven Monmouth County, NJ towns that surround Deal Lake. The Commission was chartered in 1974 by the Borough of Allenhurst, City of Asbury Park, Borough of Deal, Borough of Interlaken, Village of Loch Arbour, Neptune Township, and Ocean Township."

- ^ Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Minor Civil Divisions in New Jersey: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2019, United States Census Bureau. Accessed May 21, 2020.

- ^ Census Estimates for New Jersey April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2019, United States Census Bureau. Accessed May 21, 2020.

- ^ Compendium of censuses 1726-1905: together with the tabulated returns of 1905, New Jersey Department of State, 1906. Accessed August 23, 2013.

- ^ Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910: Population by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions, 1910, 1900, 1890, United States Census Bureau, p. 337. Accessed May 20, 2012.

- ^ Fifteenth Census of the United States : 1930—Population Volume I, United States Census Bureau, p. 710. Accessed May 20, 2012.

- ^ Table 6. New Jersey Resident Population by Municipality: 1930 - 1990 Archived May 10, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed August 9, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Census 2000 Profiles of Demographic / Social / Economic / Housing Characteristics for Asbury Park city, New Jersey Archived January 15, 2004, at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau. Accessed December 2, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e DP-1: Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000 - Census 2000 Summary File 1 (SF 1) 100-Percent Data for Asbury Park city, Monmouth County, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed December 2, 2012.

- ^ DP03: Selected Economic Characteristics from the 2006–2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates for Asbury Park city, Monmouth County, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed February 9, 2012.

- ^ Urban Enterprise Zone Tax Questions and Answers, New Jersey Department of Community Affairs, May 2009. Accessed October 28, 2019. "In 1994 the legislation was amended and ten more zones were added to this successful economic development program. Of the ten new zones, six were predetermined: Paterson, Passaic, Perth Amboy, Phillipsburg, Lakewood, Asbury Park/Long Branch (joint zone). The four remaining zones were selected on a competitive basis. They are Carteret, Pleasantville, Union City and Mount Holly."

- ^ Urban Enterprise Zone Program, New Jersey Department of Community Affairs. Accessed October 27, 2019. "Businesses participating in the UEZ Program can charge half the standard sales tax rate on certain purchases, currently 3.3125% effective 1/1/2018"

- ^ Urban Enterprise Zones Effective and Expiration Dates, New Jersey Department of Community Affairs. Accessed January 8, 2018.

- ^ Home Page, The Asbury Hotel. Accessed December 18, 2020.

- ^ "Asbury Ocean Club Hotel". Asbury Ocean Club Hotel. Retrieved September 13, 2019.

- ^ "Asbury Park Historical Society Dedicates Rainbow Room Sign", Asbury Park Historical Society. Accessed June 15, 2014. "The 16-foot metal and neon sign, removed when the Albion was demolished in 2001 for beachfront redevelopment, has since been stored briefly at the Stone Pony and then for ten years at the city's public works garage."

- ^ DiIonno, Mark. "Grim end for a grand hotel", The Star-Ledger, November 2, 2007. Accessed June 15, 2014. "The Metropolitan is part of Asbury Park history, too.... A few weeks from now, it will be a vacant lot. How the Metropolitan went from a first-class seaside resort to a broken down wreck slated demolition is a story of Asbury Park, and a reminder that time never stops claiming victims."

- ^ home page, TriCity News. Accessed August 2, 2012

- ^ Gary Wien, "Asbury Park Music Scene Loses One of its Pioneers." , September 13, 2010. Accessed August 10, 2015. http://www.newjerseystage.com/articles/getarticle.php?ID=902

- ^ Cotter, Kelly-Jane. "Novel Is A Shore Thing", Asbury Park Press, March 22, 2009. Accessed January 29, 2012.

- ^ In the Flesh: Posted by Richard Metzger In the Flesh: Blondie live in Asbury Park, NJ, 1979, Dangerous Minds. Accessed November 11, 2015.

- ^ Wise, Brian. "From Croon to Doom Metal", The New York Times, June 5, 2005. Accessed January 29, 2012. "Even so, plans for a New Jersey Music Hall of Fame center on Asbury Park, where Mr. Springsteen got his start by playing in the scrubby clubs there."

- ^ "Hip-hop in Asbury Park: Scene emerges after decades of musical segregation".

- ^ http://classicurbanharmony.net/event/asbury-park-museum-features-classic-urban-harmony-exhibit-asbury-park-west-side-music-1880-1980/

- ^ "Specs". Asbury Park Brewery. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ "Asbury Park Music and Film Festival's board of directors gets high-profile additions".

- ^ About Us, Asbury Park Music Foundation. Accessed December 18, 2020. "The mission of Asbury Park Music Foundation is to keep the Asbury Park music legacy alive by providing under-served youth with life-changing music education, helping the local music scene thrive and uniting a diverse community through music."

- ^ Makin, Bob. "Makin Waves with Asbury Park Surf Music Festival: Still a thrill", , August 1, 2018. Accessed December 18, 2020. "During the past six years, husband-and-wife team Vincent Minervino and Magdalena O’Connell have parlayed a love of surf rock into a festival, a record label, a band, a DJ business, concert promotion, and other special events. From Aug. 16 to 19, the Asbury Park Surf Music Festival returns with almost as much fun as getting tubed."

- ^ Pfeiffer, John Asbury Park Music Awards and Musical Heritage Kickoff, The Aquarian Weekly, December 1, 2010. Accessed December 18, 2010.

- ^ "Why Sea.Hear.Now 2018 Was The Best New Music Festival of the Year", The Pop Break, October 22, 2018. Accessed March 17, 2020.

- ^ Oglesby, Amanda. "Asbury Park's Sea.Hear.Now festival a major success", Asbury Park Press', September 30, 2018. Accessed March 17, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Music Mondays at Springwood Park, Asbury Park Music Foundation. Accessed March 17, 2020.

- ^ La Gorce, Tammy. "Still Rocking Hard in Asbury Park as the Bands Play On", The New York Times, May 13, 2007. Accessed July 19, 2012. "'The Wave Gathering has as much to do with music as with this town making its comeback,' said Gordon Brown, one of several organizers, a music promoter and a lifetime resident of Asbury Park who started sneaking into clubs to see up-and-coming acts 20 years ago, when he was 15."

- ^ Majeski, John. "First Saturday returns Event focuses on city shops and restaurants", Asbury Park Press, May 5, 2005. Accessed May 20, 2012. "First Saturday Night Asbury Park will return this month to the city's downtown, with businesses staying open late and shoppers finding special sales, giveaways, live music, trolley rides and refreshments."

- ^ https://visionarytattoofest.com/

- ^ History Archived January 31, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Garden State Film Festival. Accessed January 29, 2012.