Ashura

| Ashura | |

|---|---|

Ashura commemorating martyrdom of Prophet's grandson, Tehran, 2016 | |

| Official name | عَاشُورَاء ʿĀshūrāʾ (in Arabic) |

| Also called | Hosay, Tabuik, Tabot, The Day of Atonement |

| Observed by | Muslims |

| Type | Islamic and national (In some countries such as Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Iran, Lebanon, Pakistan, Bangladesh, India and Iraq) |

| Significance | Marks the day that Musa was saved by God; Marks the martyrdom of Husayn ibn Ali and members of his family |

| Observances | Fasting, mourning |

| Date | 10 Muharram |

| 2020 date | 29 August[1] |

| 2021 date | 19 August[1] |

| 2022 date | 09 August[1] |

| Frequency | Once every Islamic year |

| Part of a series on |

| Musa |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Husayn |

|---|

|

|

Ashura (Arabic: عَاشُورَاء, romanized: ʿĀshūrāʾ [ʕaːʃuːˈraːʔ]) is an Islamic holiday that occurs on the tenth day of Muharram, the first month in the Islamic lunar calendar.[4] For Muslims, Ashura marks the day in which the Islamic prophet Musa was saved by Allah when He parted the Sea while leading the children of Israel to the land of Israel. Furthermore, for Muslims, it marks the day on which the Battle of Karbala took place, resulting in the martyrdom of Husayn ibn Ali, the grandson of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a member of the Household of Muhammad (Ahl al-Bayt).

The two main practices performed on the day are fasting and mourning.[5]

Etymology

The root of the word Ashura has the meaning of tenth in Semitic languages; hence the name of the remembrance, literally translated, means "the tenth day". According to the orientalist A. J. Wensinck, the name is derived from the Hebrew ʿāsōr, with the Aramaic determinative ending.[6] The day is indeed the tenth day of the month, although some Islamic scholars offer up different etymologies.

Historical background

Musa dividing the sea

The Qurʾān mentions that God instructed Mūsā to travel at night with the Israelites and warns them that they would be captured. The Pharaoh chases the Israelites with his army after realizing that they have left during the night.[7] The Israelites exclaim to Mūsā that they would be overtaken by Pharaoh and his army. In response, God commands Mūsā to strike the Red Sea with his staff, instructing them not to fear being inundated or drowning in sea water. Upon striking the sea, Mūsā splits it into two parts, forming a path that allows the Israelites to pass through. The Pharaoh witnesses the sea splitting alongside his army, but as they also try to pass through, the sea closes in on them.[8][9]

Martyrdom of Ḥusayn

The Battle of Karbala took place within the crisis environment resulting from the succession of Yazid I.[10][11] Immediately after succession, Yazid instructed the governor of Medina to compel Ḥusayn and a few other prominent figures to pledge their allegiance (Bay'ah).[12] Ḥusayn, however, refrained from making such a pledge, believing that Yazid was openly going against the teachings of Islam and changing the sunnah of Muhammad.[13][14] He, therefore, accompanied by his household, his sons, brothers, and the sons of Hasan left Medina to seek asylum in Mecca.[12]

In Mecca, Ḥusayn learned assassins had been sent by Yazid to kill him in the holy city in the midst of Hajj. Ḥusayn, to preserve the sanctity of the city and specifically that of the Kaaba, abandoned his Hajj and encouraged others around him to follow him to Kufa without knowing the situation there had taken an adverse turn.[12]

On the way, Ḥusayn found that his messenger, Muslim ibn Aqeel, had been killed in Kufa. Ḥusayn encountered the vanguard of the army of Ubaydullah ibn Ziyad along the route towards Kufa. Ḥusayn addressed the Kufan army, reminding them that they had invited him to come because they were without an Imam. He told them that he intended to proceed to Kufa with their support, but if they were now opposed to his coming, he would return to where he had come from. In response, the army urged him to proceed by another route. Thus, he turned to the left and reached Karbala, where the army forced him not to go further and stop at a location that had limited access to water.[12]

Ubaydullah ibn Ziyad, the governor instructed Umar ibn Sa'ad, the head of the Kufan army, to offer Ḥusayn and his supporters the opportunity to swear allegiance to Yazid. He also ordered Umar ibn Sa'ad to cut off Ḥusayn and his followers from access to the water of the Euphrates.[12] On the next morning, Umar ibn Sa'ad arranged the Kufan army in battle order.[12]

The Battle of Karbala lasted from morning to sunset on 10 October 680 (Muharram 10, 61 AH). Husayn's small group of companions and family members (in total around 72 men and the women and children)[note 1][16][17] fought against a large army under the command of Umar ibn Sa'ad and were killed near the river (Euphrates), from which they were not allowed to get water. The renowned historian Abū Rayḥān al-Bīrūnī states:

… [T]hen fire was set to their camp and the bodies were trampled by the hoofs of the horses; nobody in the history of the human kind has seen such atrocities.[18]

Once the Umayyad troops had murdered Ḥusayn and his male followers, they looted the tents, stripped the women of their jewelry, and took the skin upon which Zain al-Abidin was prostrate. Ḥusayn's sister Zaynab was taken along with the enslaved women to the caliph in Damascus when she was imprisoned and after a year eventually was allowed to return to Medina.[19][20]

Commemoration of the death of Husayn ibn Ali

History of the commemoration by Shia

According to Ignác Goldziher,

[E]ver since the black day of Karbala, the history of this family … has been a continuous series of sufferings and persecutions. These are narrated in poetry and prose, in a richly cultivated literature of martyrologies … 'More touching than the tears of the Shi'is' has even become an Arabic proverb.[21]

The first assembly (majlis) of the Commemoration of Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī is said to have been held by Zaynab in prison. In Damascus, too, she is reported to have delivered a poignant oration. The prison sentence ended when Husayn's four-year-old daughter, Ruqayyah bint Husayn, died in captivity. She would often cry in prison to be allowed to see her father. She is believed to have died when she saw her father's mutilated head. Her death caused an uproar in the city, and Yazid, fearing a potential uprising, freed the captives.[22]

Imam Zayn Al Abidin said the following:

It is said that for forty years whenever food was placed before him, he would weep. One day a servant said to him, 'O son of Allah's Messenger! Is it not time for your sorrow to come to an end?' He replied, 'Woe upon you! Jacob the prophet had twelve sons, and Allah made one of them disappear. His eyes turned white from constant weeping, his head turned grey out of sorrow, and his back became bent in gloom,[note 2] though his son was alive in this world. But I watched while my father, my brother, my uncle, and seventeen members of my family were slaughtered all around me. How should my sorrow come to an end?'[note 3][23][24]

Husayn's grave became a pilgrimage site among Shia Muslims only a few years after his death. A tradition quickly developed of pilgrimage to the Imam Husayn Shrine and the other Karbala martyrs, known as Ziarat ashura.[25] The Umayyad and Abbasid caliphs tried to prevent construction of the shrines and discouraged pilgrimage to the sites.[26] The tomb and its annexes were destroyed by the Abbasid caliph Al-Mutawakkil in 850–851 and Shia pilgrimage was prohibited, but shrines in Karbala and Najaf were built by the Buwayhid emir 'Adud al-Daula in 979–80.[27]

Public rites of remembrance for Husayn's martyrdom developed from the early pilgrimages.[28] Under the Buyid dynasty, Mu'izz ad-Dawla officiated at public commemoration of Ashura in Baghdad.[29] These commemorations were also encouraged in Egypt by the Fatimid caliph al-'Aziz.[30] With the recognition of

Twelvers as the official religion by the Safavids, Mourning of Muharram extended throughout the first ten days of Muharram.[25]

Azadari (mourning) rituals

The words Azadari (Persian: عزاداری) which mean mourning and lamentation; and Majalis-e Aza have been exclusively used in connection with the remembrance ceremonies for the martyrdom of Imam Hussain. Majalis-e Aza, also known as Aza-e Husayn, includes mourning congregations, lamentations, matam and all such actions which express the emotions of grief and above all, repulsion against what Yazid stood for.[31]

These religious customs show solidarity with Husayn and his family. Through them, people mourn Husayn's death and express regret for the fact that they were not present at the battle to fight and save Husayn and his family.[32][33]

Tuwairij run

Tuwairij run is the name of a ceremony in which millions of people on the day of Ashura from an area called Tuwairij in 22 km run and mourning on side of the Imam Husayn Shrine.[34] this ceremony is considered as the biggest observance of religious activities in the world.[35][36] The importance of this ceremony has been formed since Moḥammad Mahdī Baḥr al-ʿUlūm was quoted as saying that Hujjat bin Hasan was present at this ceremony.[37]

Millions of marches

Every year millions of people attend this religious ceremony to mourn Hussein ibn Ali and his companions.[38][39][40][41][42]

History

Tuwairij was first run on Ashura 1855 when people were at the house of Seyyed Saleh Qazvini after the mourning ceremony and the recitation of the murder of Husain bin ‘Ali they cried so much for the grief and sorrow that they lost their loved ones because of this tragedy.due to this tragedy they asked Seyyed Saleh to run to the imam's shrine to offer his condolences. Seyyed Saleh also accepted this request and went to the shrine with all the mourners. in this march other mourners joined them.[43][44][45][46]

Prohibition of the march

The march was banned by Saddam Hussein’s Ba‘athist regime between 1991 and 2003.[47][48] However, despite the ban, Tuwairij was held and the regime executed many participants.[citation needed] This religious ceremony was held in public after 2003, and its participation has steadily increased from outside of Iraq.[49]

Popular customs

After almost 12 centuries, five types of major rituals were developed around the battle of Karbala. These rituals include the memorial services (majalis al-ta'ziya), the visitation of Husayn's tomb in Karbala particularly on the occasion of the tenth day of Ashura and the fortieth day after the battle (Ziyarat Ashura and ziyarat al-Arba'in), the public mourning processions (al-mawakib al-husayniyya) or the representation of the battle of Karbala in the form of a play (the shabih), and the flagellation (tatbir).[50] Some Shia Muslims believe that taking part in Ashura washes away their sins.[51] A popular Shia saying has it that "a single tear shed for Husayn washes away a hundred sins".[52]

For Shia Muslims, the commemoration of Ashura is not a festival but rather a sad event, while Sunni Muslims view it as a victory God gave to Moses. For Shia Muslims, it is a period of intense grief and mourning. Mourners congregate at a mosque for sorrowful, poetic recitations such as marsiya, noha, , and soaz performed in memory of the martyrdom of Husayn, lamenting and grieving to the tune of beating drums and chants of "Ya Hussain". Also, Ulamas give sermons with themes of Husayn's personality and position in Islam, and the history of his uprising. The Sheikh of the mosque retells the Battle of Karbala to allow his listeners to relive the pain and sorrow endured by Husayn and his family and they read Maqtal Al-Husayn.[50][53] In some places, such as Iran, Iraq, and the Arab states of the Persian Gulf, passion plays known as Ta'zieh[54] are performed, reenacting the Battle of Karbala and the suffering and martyrdom of Husayn at the hands of Yazid. In the Caribbean islands of Trinidad and Tobago and Jamaica Ashura, known locally as 'Hussay' or Hosay is commemorated for the grandson of Muhammad, but its celebration has adopted influence from other religions including Roman Catholic, Hindu, and Baptists, making it a mixture of different cultures and religion. The event is attended by both Muslims and non-Muslims depicting an environment of mutual respect and tolerance.[55][56] For the duration of the remembrance, it is customary for mosques and some people to provide free meals (Nazri or Votive Food) on certain nights of the month to all people.[57]

Certain traditional flagellation rituals such as Talwar zani (talwar ka matam or sometimes tatbir) use a sword. Other rituals such as zanjeer zani or zanjeer matam involve the use of a zanjeer (a chain with blades).[58] This is not without controversy however as some Shia clerics have denounced the practice saying "it creates a backward and negative image of their community." Believers are instead encouraged to donate blood to those in need.[59] On Ashura, very few Shia Muslims observe mourning with a blood donation, which is called "Qame Zani", and flailing. This mourning is considered to be a way for most Shia Muslims and most of them are against this kind of mourning.[60] In some areas, such as in the Shia suburb of Beirut, Shia communities organize blood donation drives with organizations like the Red Cross or the Red Crescent on Ashura as a replacement for self-flagellation rituals like tatbir and qame zani.[61]

Indian Shia Muslims carry out a Ta'ziya procession on day of Ashura in Barabanki, India, January 2009.

A historic Ashura celebration in Jamaica, which is known locally as Hussay or Hosay

Shia Muslims carry out an Al'am procession on the day of Ashura in Barabanki, India, January 2009.

Nakhl gardani in cities and villages of Iran

Significance

| Part of a series on Islam Shia Islam |

|---|

|

|

|

Shia Islam

Ashura is remembered by Jafaris, Qizilbash Alevi-Turks, and Bektashis together in Ottoman Empire.[63] This day is of particular significance to Twelver Shia and Alawites, who consider Husayn (the grandson of Muhammad) Ahl al-Bayt, the third Imam to be the rightful successor of Muhammad.[citation needed]

According to Kamran Scot Aghaie, "The symbols and rituals of Ashura have evolved over time and have meant different things to different people. However, at the core of the symbolism of Ashura is the moral dichotomy between worldly injustice and corruption on the one hand and God-centered justice, piety, sacrifice and perseverance on the other. Also, Shiite Muslims consider the remembrance of the tragic events of Ashura to be an important way of worshipping God in a spiritual or mystical way."[64]

Shia Muslims make pilgrimages on Ashura, as they do forty days later on ʾArbaʿīn, to the Mashhad al-Husayn, the shrine in Karbala, Iraq, that is traditionally held to be Husayn's tomb. On this day Shia is in remembrance, and mourning attire is worn. They refrain from listening to or playing music since Arabic culture generally considers music impolite during death rituals. It is a time for sorrow and for showing respect for the person's passing, and it is also a time for self-reflection when one commits oneself completely to the mourning of Husayn. Shia Muslims do not plan weddings and parties on this date. They mourn by crying and listening to recollections of the tragedy and sermons on how Husayn and his family were martyred. This is intended to connect them with Husayn's suffering and martyrdom, and the sacrifices he made to keep Islam alive. Husayn's martyrdom is widely interpreted by Shia Muslims as a symbol of the struggle against injustice, tyranny, and oppression.[65] Shia Muslims believe the Battle of Karbala was between the forces of good and evil, with Husayn representing good and Yazid representing evil.[66]

Shia imams strongly insist that the day of Ashura should not be celebrated as a day of joy and festivity. The day of Ashura, according to Eighth Shia Imam Ali al-Rida, must be observed as a day of rest, sorrow, and total disregard of worldly matters.[67]

Some of the events associated with Ashura are held in special congregation halls known as "Imambargah" and Hussainia.[68] The World Sunni Movement celebrates this day as National Martyrs' Day of Muslim nation under the direction of Syed Imam Hayat.[69]

Sunni Islam

Sunnis regard fasting during Ashura as recommended, though not obligatory, having been superseded by the Ramadan fast.[70][71] According to hadith record in Sahih Bukhari, Ashura was already known as a commemorative day during which some Meccan residents used to observe customary fasting. Muhammad fasted on the day of Ashura, 10th Muharram, in Mecca. When fasting during the month of Ramadan became obligatory, the fast of Ashura was made non-compulsory.[72][73]

Judaism

According to Muslim tradition, the Jews also fasted on the tenth day. According to Sunni Muslim tradition, Ibn Abbas narrated that Muhammad came to Medina and saw the Jews fasting on the tenth day of Muharram. He asked, "What is this?" They said, "This is a good day, this is the day when Allah saved the Children of Israel from their enemy and Musa (Moses) fasted on this day." He said, "We have more claim over Musa than you." So he fasted on the day and told the people to fast.[72][73][74][75] This tenth in question is believed to be the tenth of the Jewish month of Tishri, which is Yom Kippur in Judaism.[76] The Torah designates the tenth day of the seventh month as holy and a fast (Lev. 16, Lev. 23, Num. 29). The word "tenth" in Hebrew is ʿAsarah or ʿAsharah (עשרה), which is from the same Semitic root ʿ-SH-R. According to this tradition, Muhammad continued to observe the veneration of Ashura modeled on its Jewish prototype in late September until shortly before his death, when the verse of Nasi' was revealed and the Jewish-type calendar adjustments of the Muslims became prohibited. From then on, Ashura became distinct from its Jewish predecessor of Yōm Kippur.[77] However, some differ with the claim that Ashura used to correspond with Yōm Kippur due to the fact that the hadith records it was a day of celebration for the Jews not of atonement and the word Ashura may simply come from the Arabic word ʿasharaʾ, also meaning ten.[78]

Socio-political aspects

Commemoration of Ashura has great socio-political value for the Shia, who have been a minority throughout their history. According to the prevailing conditions at the time of the commemoration, such reminiscences may become a framework for implicit dissent or explicit protest. It was, for instance, used during the Islamic Revolution of Iran, the Lebanese Civil War, the Lebanese resistance against the Israeli military presence and in the 1990s Uprising in Bahrain. Sometimes the Ashura commemorations associate the memory of Al-Husayn's martyrdom with the conditions of Islam and Muslims in reference to Husayn's famous quote on the day of Ashura: "Every day is Ashura, every land is Karbala".[79]

From the period of the Iranian Constitutional Revolution (1905–1911) onward, mourning gatherings increasingly assumed a political aspect. Following an old established tradition, preachers compared the oppressors of the time with Imam Husayn's enemies, the umayyads.[80]

The political function of commemoration was very marked in the years leading up to the Islamic Revolution of 1978–79, as well as during the revolution itself. In addition, the implicit self-identification of the Muslim revolutionaries with Imam Husayn led to a blossoming of the cult of the martyr, expressed most vividly, perhaps, in the vast cemetery of Behesht-e Zahra, to the south of Tehran, where the martyrs of the revolution and the war against Iraq are buried.[80]

On the other hand, some governments have banned this commemoration. In the 1930s Reza Shah forbade it in Iran. The regime of Saddam Hussein saw this as a potential threat and banned Ashura commemorations for many years.[81] In the 1884 Hosay massacre, 22 people were killed in Trinidad and Tobago when civilians attempted to carry out the Ashura rites, locally known as Hosay, in defiance of the British colonial authorities.[82]

Terrorist attacks during Ashura

Terrorist attacks against Shia Muslims have occurred in several countries, on the day of Ashura, the repeated experience of which has produced an "interesting" feedback effect in Shia history.[83]

- 1818–1820: Syed Ahmad Barelvi and Shah Ismail Dihlavi took up arms to stop Ashura commemoration in North India. They were the pioneers of anti-Shia terrorism in the subcontinent. Barbara Metcalf noting:

A second group of abuses Syed Ahmad held were those that originated from Shi’i influence. He particularly urged Muslims to give up the keeping of ta’ziyahs, the replicas of the tombs of the martyrs of Karbala taken in procession during the mourning ceremony of Muharram. Muhammad Isma’il wrote, "a true believer should regard the breaking of a tazia by force to be as virtuous an action as destroying idols. If he cannot break them himself, let him order others to do so. If this even be out of his power, let him at least detest and abhor them with his whole heart and soul". Sayyid Ahmad himself is said, no doubt with considerable exaggeration, to have torn down thousands of imambaras, the building that house the taziyahs.[84]

- 1940: Bomb thrown on Ashura Procession in Delhi, 21 February[85]

- 1994: explosion of a bomb at the Imam Reza shrine, 20 June, in Mashhad, Iran, 20 people killed[86]

- 2004: bomb attacks, during Shia pilgrimage to Karbala, 2 March, Karbala, Iraq, 178 people killed and 5000 injured[87]

- 2008: clashes, between Iraqi troops and members of a Shia cult, 19 January, Basra and Nasiriya, Iraq, 263 people killed[88]

- 2009: explosion of a bomb, during the Ashura procession, 28 December, Karachi, Pakistan, dozens of people killed and hundreds injured[89]

- 2010: detention of 200 Shia Muslims, at a shop house in Sri Gombak known as Hauzah Imam Ali ar-Ridha (Hauzah ArRidha), 15 December, Selangor, Malaysia[90]

- 2011: explosion of a bomb, during the Ashura procession, 28 December, Hilla and Baghdad, Iraq, 5 December 30 people killed[91]

- 2011: suicide attack, during the Ashura procession, Kabul, Afghanistan, 6 December 63 people killed[92]

- 2015: three explosions, during the Ashura procession, mosque in Dhaka, Bangladesh, 24 October, one person killed and 80 people injured[93]

In the Gregorian calendar

While Ashura is always on the same day of the Islamic calendar, the date on the Gregorian calendar varies from year to year due to differences between the two calendars, since the Islamic calendar is a lunar calendar and the Gregorian calendar is a solar calendar. Furthermore, the appearance of the crescent moon that is used to determine when each Islamic month begins varies from country to country due to the different geographic locations.[citation needed]

| AH | Gregorian date |

|---|---|

| 1438 | 12 October 2016 (Middle East: Lebanon, Iraq, Iran) |

| 1439 | 1 October 2017 (Middle East: Lebanon, Iraq, Iran)[94] |

| 1440 | 21 September 2018 |

| 1441 | 10 September 2019 |

| 1442 | 30 August 2020[95] |

| 1443 | 18 August 2021[95] |

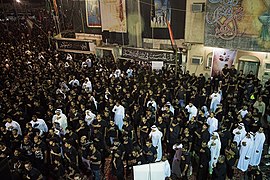

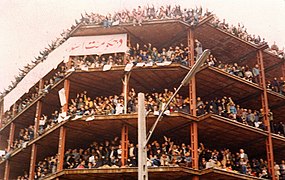

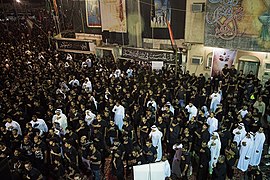

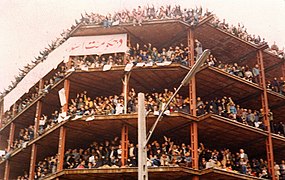

Gallery

Shias mourning in Iran

Ashura procession in Tehran

Shias mourning in Chiniot

Tuwairij Run in Karbala, Iraq

Tabuiks being lowered in Pariaman, Indonesia

Shias congregating outside the Sydney Opera House in Australia.

Shias mourning in Qatif, Saudi Arabia

Ashura in Syria

Ashura Demonstration in Tehran in 1978

2016 Ashura mourning in Imam Husayn Square

See also

- Al-Tall Al-Zaynabiyya

- Ashoura (missile)

- Ashura in Algeria

- Ashura in Morocco

- Ashure

- Battle of Karbala

- Bibi-Ka-Alam

- Day of Tasu'a

- Hobson Jobson

- List of casualties in Husayn's army at the Battle of Karbala

- Mourning of Muharram

- Passage of the Red Sea

- Passover

- Persecution of Shia Muslims

- Sebiba

- Yom Kippur

- Ziyarat Ashura

Notes

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d "When is Ashura Day Worldwide". 30 September 2017. Archived from the original on 28 September 2019. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ^ "Holidays in Iran in 2017".

- ^ "Islamic Calendar". islamicfinder.

- ^ "Shiite History Beliefs and Differences Between Sunnis and Shiites: Muslim Sects and Sunnis". Archived from the original on 2 February 2015. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ^ Morrow, John Andrew. Islamic Images and Ideas: Essays on Sacred Symbolism. McFarland & Co, 2013. pp. 234–36. ISBN 978-0786458486

- ^ A. J. Wensinck, "Āshūrā", Encyclopaedia of Islam 2. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- ^ Raouf Ghattas; Carol Ghattas (2009). A Christian Guide to the Quran:Building Bridges in Muslim Evangelism. Kregel Academic. p. 125. ISBN 9780825426889. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- ^ Quran 7:136

- ^ Halim Ozkaptan (2010). Islam and the Koran- Described and Defended. p. 41. ISBN 9780557740437. Archived from the original on 9 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- ^ G.R., Hawting (2012). "Yazīd (I) b. Muʿāwiya". Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_8000.

- ^ Hitti, Philip K. (1961). The Near East in History A 5000 Year Story. Literary Licensing, LLC. ISBN 978-1258452452. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Madelung, Wilferd. "Ḥisayn B. 'Ali i. Life and Significance in Shi'ism". Encyclopædia Iranica Online. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ^ "Al Bidayah wa al-Nihayah".[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Al-Sawa'iq al-Muhriqah".[permanent dead link]

- ^ Hoseini-e Jalali, Mohammad-Reza (1382). Jehad al-Imam al-Sajjad (in Persian). Translated by Musa Danesh. Iran, Mashhad: Razavi, Printing & Publishing Institute. pp. 214–17.

- ^ "در روز عاشورا چند نفر شهید شدند؟". Archived from the original on 26 March 2013.

- ^ "فهرست اسامي شهداي كربلا". Velaiat.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ Chelkowski, Peter J. (1979). Ta'ziyeh: Ritual and Drama in Iran. New York. p. 2.

- ^ Madelung, Wilferd. "ʿAlī B. Ḥosayn B. ʿAlī B. Abī Tāleb". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- ^ Donaldson, Dwight M. (1933). The Shi'ite Religion: A History of Islam in Persia and Irak. Burleigh Press. pp. 101–11.

- ^ Goldziher, Ignác (1981). Introduction to Islamic Theology and Law. Princeton. p. 179.

- ^ "Zaynab Bint Ali". Encyclopedia of Religion. Retrieved 19 January 2008.

- ^ Sharif al-Qarashi, Bāqir (2000). The Life of Imām Zayn al-Abidin (as). Translated by Jāsim al-Rasheed. Iraq: Ansariyan Publications, n.d. Print.

- ^ Imam Ali ubnal Husain (2009). Al-Saheefah Al-Sajjadiyyah Al-Kaamelah. Translated with an Introduction and annotation by Willian C. Chittick With a foreword by S. H. M. Jafri. Qum, The Islamic Republic of Iran: Ansariyan Publications.

- ^ a b "Hosayn B. Ali in Popular Shiism". Encyclopedia of Iranica. Archived from the original on 17 January 2008. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ al Musawi, 2006, p. 51.

- ^ Litvak, 1998, p. 16.

- ^ Nafasul Mahmoom. JAC Developer. pp. 12–. GGKEY:RQAZ12CNGF5.

- ^ Chelkowski, Peter (1 January 1985). "Shia Muslim Processional Performances". The Drama Review: TDR. 29 (3): 18–30. doi:10.2307/1145650. JSTOR 1145650.

- ^ Blank, Jonah (15 April 2001). Mullahs on the Mainframe: Islam and Modernity Among the Daudi Bohras. University of Chicago Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0226056777.

- ^ Jean, Calmard (2011). "AZĀDĀRĪ". iranicaonline.

- ^ Bird, Steve (28 August 2008). "Devout Muslim guilty of making boys beat themselves during Shia ceremony". The Times. London. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ "British Muslim convicted over teen floggings". Alarabiya.net. 27 August 2008. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ "1 million pilgrims perform Tuwairij rush in Karbala". Aswat al-Iraq. 27 December 2009. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ "مراسم "هروله طویریج"؛ یکی از عظیم ترین گردهمایی های جهان". میدل ایست نیوز (in Persian). 31 October 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ "'Tuwairij run' takes place in Holy city of Karbala, Iraq". iranpress.com. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ "حماسی ترین مراسم عاشورایی در كربلا آغاز شد". ایرنا (in Persian). 1 October 2017. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ "Deaths at Iraq's Ashura festival will not deter millions of worshippers". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ "Iraq stampede kills 31 at Ashura commemorations in Karbala". BBC News. 10 September 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ "31 Iraqis killed in Karbala in a stampede on Yaum-e-Ashura". The Siasat Daily. 11 September 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ "دسته میلیونی طویریج در کربلا/ تصاویر – کرب و بلا". سایت تخصصی امام حسین علیه السلام (in Persian). Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ Szanto, Edith. "The largest contemporary Muslim pilgrimage isn't the hajj to Mecca, it's the Shiite pilgrimage to Karbala in Iraq". The Conversation. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "تجلی عشق حسینی در " رَکْضَة طُوَیرِیج "". shooshan.ir. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ "داستان دسته طويريج چیست؟ + تصاویر". مشرق نیوز (in Persian). 17 November 2013. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ Nawaret (8 December 2011). "ماهي ركضة طويريج في العراق". جريدة نورت (in Arabic). Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ "أصل-ركضة-طويريج-ومنشؤها".

- ^ "عزاء ركضة طويريج نشأته وتاريخه". شيعة ويفز – ShiaWaves Arabic (in Arabic). 19 September 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ "تاریخچهای از دسته عزاداری طویریج – کرب و بلا". سایت تخصصی امام حسین علیه السلام (in Persian). Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ "ركضة طويريج .. من أكبر الفعاليات الدينية في العالم.. تعرف على تأريخها". almasalah.com. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ a b Nakash, Yitzhak (1 January 1993). "An Attempt To Trace the Origin of the Rituals of Āshurā¸". Die Welt des Islams. 33 (2): 161–81. doi:10.1163/157006093X00063. – via Brill (subscription required)

- ^ David Pinault, "Shia Lamentation Rituals and Reinterpretations of the Doctrine of Intercession: Two Cases from Modern India," History of Religions 38 no. 3 (1999): 285–305.

- ^ Nasr, Vali, "The Shia Revival", Norton, 2006, p. 50

- ^ Puchowski, Douglas (2008). The Concise Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Volume 2. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415994040.

- ^ Chelkowski, Peter (ed.) (1979) Taʻziyeh, ritual and drama in Iran New York University Press, New York, ISBN 0814713750

- ^ Hosay Festival, Westmoreland, Jamaica

- ^ http://old.jamaica-gleaner.com/pages/history/story0057.htm title= Out Of Many Cultures The People Who Came The Arrival Of The Indians

- ^ Rezaian, Jason. "Iranians relish free food during month of mourning". washingtonpost.

- ^ "Scars on the backs of the young". New Statesman. UK. 6 June 2005. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ "Ashoura day: Why Muslims fast and mourn on Muharram 10". Al Jazeera. 10 October 2016.

- ^ "Ashura observed with blood streams to mark Karbala tragedy". Jafariya News Network. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ Edith Szanto, "Sayyida Zaynab in the State of Exception: Shi'i Sainthood as 'Qualified Life' in Contemporary Syria", International Journal of Middle East Studies 44 no. 2 (2012): 285–99.

- ^ Turkish Alevis are mourning on this day for the remembrance of the death of Huseyn bin Ali at Kerbala in Irak.

- ^ Turkish Alevis mourn on this day to commemorate the death of Huseyn bin Ali at Kerbala in Irak.

- ^ Cornell, Vincent J.; Kamran Scot Aghaie (2007). Voices of Islam. Westport, CN: Praeger Publishers. pp. 111–12. ISBN 978-0275987329. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ^ "Karbala', an Enduring Paradigm". Al-islam.org. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ Dabashi, Hamid (2008). Islamic Liberation Theology: Resisting the Empire. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415771559.

- ^ Ayoub, Shi'ism (1988), pp. 258–59

- ^ Juan Eduardo Campo (2009). Encyclopedia of Islam. Infobase Publishing. pp. 318–. ISBN 978-1438126968.

- ^ প্রতিবেদক, নিজস্ব (13 September 2019). "কারবালা দিবস উপলক্ষে বিশ্ব সুন্নি আন্দোলন, যুক্তরাষ্ট্রের সমাবেশ". Prothomalo (in Bengali). Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ Sahih Muslim, (Hadith-2499)

- ^ Emmanuel Sivan. "Sunni Radicalism in the Middle East and the Iranian Revolution". International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 21, No. 1. (February 1989), pp. 1–30

- ^ a b Sahih Bukhari Book 31 Hadith 222, Book 55 Hadith 609, and Book 58 Hadith 279, [1]; Sahih Muslim Book 6 Hadith 2518, 2519, 2520 [2]

- ^ a b Javed Ahmad Ghamidi. Mizan, The Fast Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Al-Mawrid

- ^ Morrow, John Andrew. Islamic Images and Ideas: Essays on Sacred Symbolism. McFarland & Co, 2013. pp. 234–36. ISBN 978-0786458486

- ^ Katz, Marion Holmes The Birth of The Prophet Muhammad: Devotional Piety in Sunni Islam. Routledge, 2007. pp. 113–15. ISBN 978-1135983949

- ^ Prophet Muhammad and the Origins of Islam, Francis E. Peters, SUNY Press, 1994, p. 204.

- ^ Prophet Muhammad and the Origins of Islam, Francis E. Peters, SUNY Press, 1994, p. 204.

- ^ "Is the Fast of Ashura Similar to Passover or Yom Kippur?". Muslim Matters. Muslim Matters. 6 December 2011. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ^ IslamOnline – Art & Entertainment Section Archived 11 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Calmard, J. "'Azaúdaúrè". Encyclopedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 4 May 2008. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ Melton, J. Gordon; Baumann, Martin (2010). Religions of the World [6 volumes]: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices. ABC-CLIO. p. 211. ISBN 978-1598842036.

- ^ Anthony, Michael (2001). Historical Dictionary of Trinidad and Tobago. Scarecrow Press, Inc. Lanham, MD and London. ISBN 978-0810831735.

- ^ Hassner, Ron E. (2016). Religion on the Battlefield. Cornell University Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0801451072.

Violence during Ashura.

- ^ B. Metcalf, Islamic revival in British India: Deoband, 1860–1900, p. 58, Princeton University Press (1982).

- ^ J. N. Hollister, The Shi'a of India, p. 178, Luzac and Co, London, (1953).

- ^ Raman, B. (7 January 2002). "Sipah-E-Sahaba Pakistan, Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, Bin Laden & Ramzi Yousef". Archived from the original on 29 April 2009.

- ^ "Blasts at Shia Ceremonies in Iraq Kill More Than 140". The New York Times. 2 March 2004. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- ^ "Iraqi Shia pilgrims mark holy day". bbc.co.uk. 19 January 2008. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ^ "Reuters News clip". Youtube.com. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ "Malaysian Wahhabi Extremists Attacked Shia Mourners, Detain 200 + PIC". abna.ir. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ "Deadly bomb attacks on Shia pilgrims in Iraq". bbc.co.uk. 5 December 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ Harooni, Mirwais (6 December 2011). "Blasts across Afghanistan target Shia, 59 dead". Reuters. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ "Dhaka blasts: One dead in attack on Shia Ashura ritual". BBC News. 24 October 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ "Holidays in Iran in 2017".

- ^ a b "Ashura – Calendar Date". www.calendardate.com. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

Sources

- Litvak, Meir (1998). Shi'i Scholars of Nineteenth-Century Iraq: The Ulama of Najaf and Karbala. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-89296-1

- al Musawi, Muhsin (2006). Reading Iraq: Culture and Power and Conflict. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 1-84511-070-6

- al Mufid, al-Shaykh Muhammad (December 1982 (1st ed.)). Kitab Al-Irshad. Tahrike Tarsile Quran. ISBN 0-940368-12-9, 978-0-940368-12-5

- al-Azdi, abu Mikhnaf, Maqtal al-Husayn. Shia Ithnasheri Community of Middlesex (PDF)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ashura. |

- Gordon B. Coutts (Scottish/American, 1868–1937) A Large Oil on Canvas Depicting "The Ashura Rituals, Tangier" (Arabic: عاشوراء ʻĀshūrā’ – Urdu: عاشورا – Persian: عاشورا – Turkish: Aşure Günü). Signed and inscribed: 'Gordon Coutts/TANGIER (lower right). c. 1920

- Is Aashura a day of mourning or rejoicing?

- Ashura – The Historical Significance and Rewards on Islam Freedom

- Events on the day of Ashura

- "Ashura" An article in Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- What is Ashura? (BBC News)

- What Is Ashura? – by Abdul-Ilah As-Saadi on Al Jazeera

- Ashura Australia – Official website of the Annual Ashura Procession in Sydney

- Shia days of remembrance

- Islamic holy days

- Mourning of Muharram

- Islamic terminology

- History of Islam

- Family of Muhammad

- People killed at the Battle of Karbala

- Hussainiya

- Ashura

- Sufism in Algeria

- Public holidays in Algeria

- Festivals in Algeria

- History of Shia