Aspartame

| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈæspərteɪm/ or /əˈspɑːrteɪm/ |

| IUPAC name

Methyl L-α-aspartyl-L-phenylalaninate

| |

| Other names

N-(L-α-Aspartyl)-L-phenylalanine,

1-methyl ester | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.041.132 |

| EC Number |

|

| E number | E951 (glazing agents, ...) |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| Properties | |

| C14H18N2O5 | |

| Molar mass | 294.307 g·mol−1 |

| Density | 1.347 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 246–247 °C (475–477 °F; 519–520 K) |

| Boiling point | Decomposes |

| Sparingly soluble | |

| Solubility | Slightly soluble in ethanol |

| Acidity (pKa) | 4.5–6.0[2] |

| Hazards[3] | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

1

1

0 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

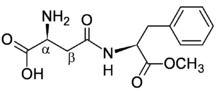

Aspartame is an artificial non-saccharide sweetener 200 times sweeter than sucrose, and is commonly used as a sugar substitute in foods and beverages.[3] It is a methyl ester of the aspartic acid/phenylalanine dipeptide with the trade names NutraSweet, Equal, and Canderel.[3] Aspartame was first made in 1965 and approved for use in food products by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1981.[4]

Aspartame is one of the most rigorously tested food ingredients.[5] Reviews by over 100 governmental regulatory bodies found the ingredient safe for consumption at current levels.[6][7][8][9][10] As of 2018, several reviews of clinical trials showed that using aspartame in place of sugar reduces calorie intake and body weight in adults and children.

Uses[]

Aspartame is around 180 to 200 times as sweet as sucrose (table sugar). Due to this property, even though aspartame produces 4 kcal (17 kJ) of energy per gram when metabolized, the quantity of aspartame needed to produce a sweet taste is so small that its caloric contribution is negligible.[7] The taste of aspartame and other artificial sweeteners differs from that of table sugar in the times of onset and how long the sweetness lasts, though aspartame comes closest to sugar's taste profile among approved artificial sweeteners.[11] The sweetness of aspartame lasts longer than that of sucrose, so it is often blended with other artificial sweeteners such as acesulfame potassium to produce an overall taste more like that of sugar.[12]

Like many other peptides, aspartame may hydrolyze (break down) into its constituent amino acids under conditions of elevated temperature or high pH. This makes aspartame undesirable as a baking sweetener, and prone to degradation in products hosting a high pH, as required for a long shelf life. The stability of aspartame under heating can be improved to some extent by encasing it in fats or in maltodextrin. The stability when dissolved in water depends markedly on pH. At room temperature, it is most stable at pH 4.3, where its half-life is nearly 300 days. At pH 7, however, its half-life is only a few days. Most soft-drinks have a pH between 3 and 5, where aspartame is reasonably stable. In products that may require a longer shelf life, such as syrups for fountain beverages, aspartame is sometimes blended with a more stable sweetener, such as saccharin.[13]

Descriptive analyses of solutions containing aspartame report a sweet aftertaste as well as bitter and off-flavor aftertastes.[14] In products such as powdered beverages, the amine in aspartame can undergo a Maillard reaction with the aldehyde groups present in certain aroma compounds. The ensuing loss of both flavor and sweetness can be prevented by protecting the aldehyde as an acetal.

Safety and health effects[]

The safety of aspartame has been studied since its discovery[8] and it is one of the most rigorously tested food ingredients.[15] Aspartame has been deemed safe for human consumption by over 100 regulatory agencies in their respective countries, including the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA),[6][16][17] UK Food Standards Agency,[18] the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA),[19] Health Canada,[20] Australia, and New Zealand.[9]

As of 2017, reviews of clinical trials showed that using aspartame (or other non-nutritive sweeteners) in place of sugar reduces calorie intake and body weight in adults and children.[21][22][23]

A 2017 review of metabolic effects by consuming aspartame found that it did not affect blood glucose, insulin, total cholesterol, triglycerides, calorie intake, or body weight. While high-density lipoprotein levels were higher compared to control, they were lower compared to sucrose.[24]

Phenylalanine[]

High levels of the naturally occurring essential amino acid phenylalanine are a health hazard to those born with phenylketonuria (PKU), a rare inherited disease that prevents phenylalanine from being properly metabolized.[25] Because aspartame contains a small amount of phenylalanine, foods containing aspartame sold in the United States must state: "Phenylketonurics: Contains Phenylalanine" on product labels.[6]

In the UK, foods that contain aspartame are required by the Food Standards Agency to list the substance as an ingredient, with the warning, "Contains a source of phenylalanine". Manufacturers are also required to print '"with sweetener(s)" on the label close to the main product name on foods that contain "sweeteners such as aspartame" or "with sugar and sweetener(s)" on "foods that contain both sugar and sweetener".[26]

In Canada, foods that contain aspartame are required to list aspartame among the ingredients, include the amount of aspartame per serving, and state that the product contains phenylalanine.[27]

Phenylalanine is one of the essential amino acids and is required for normal growth and maintenance of life.[25] Concerns about the safety of phenylalanine from aspartame for those without phenylketonuria center largely on hypothetical changes in neurotransmitter levels as well as ratios of neurotransmitters to each other in the blood and brain that could lead to neurological symptoms. Reviews of the literature have found no consistent findings to support such concerns,[8][10] and while high doses of aspartame consumption may have some biochemical effects, these effects are not seen in toxicity studies to suggest aspartame can adversely affect neuronal function.[25] As with methanol and aspartic acid, common foods in the typical diet such as milk, meat, and fruits, will lead to ingestion of significantly higher amounts of phenylalanine than would be expected from aspartame consumption.[10]

Cancer[]

Reviews have found no association between aspartame and cancer.[7][8][10][28][29] This position is supported by multiple regulatory agencies like the FDA[30] and EFSA as well as scientific bodies such as the National Cancer Institute.[31] The EFSA, FDA, and the US National Cancer Institute state that aspartame is safe for human consumption.[6][32][31]

Neurotoxicity symptoms[]

Reviews found no evidence that low doses of aspartame would plausibly lead to neurotoxic effects.[7][8][10][33] A review of studies on children did not show any significant findings for safety concerns with regard to neuropsychiatric conditions such as panic attacks, mood changes, hallucinations, ADHD, or seizures by consuming aspartame.[34]

Headaches[]

Headaches are the most common symptom reported by consumers.[7] While one small review noted aspartame is likely one of many dietary triggers of migraines, in a list that includes "cheese, chocolate, citrus fruits, hot dogs, monosodium glutamate, aspartame, fatty foods, ice cream, caffeine withdrawal, and alcoholic drinks, especially red wine and beer,"[35] other reviews have noted conflicting studies about headaches[7][36] and other studies lack any evidence and references to support this claim.[8][10][34]

Mechanism of action[]

The perceived sweetness of aspartame (and other sweet substances like acesulfame K) in humans is due to its binding of the heterodimer G protein-coupled receptor formed by the proteins TAS1R2 and TAS1R3.[37] Aspartame is not recognized by rodents due to differences in the taste receptors.[38]

Metabolites[]

Aspartame is rapidly hydrolyzed in the small intestines. Even with ingestion of very high doses of aspartame (over 200 mg/kg), no aspartame is found in the blood due to the rapid breakdown.[7] Upon ingestion, aspartame breaks down into residual components, including aspartic acid, phenylalanine, methanol,[39] and further breakdown products including formaldehyde[40] and formic acid. Human studies show that formic acid is excreted faster than it is formed after ingestion of aspartame. In some fruit juices, higher concentrations of methanol can be found than the amount produced from aspartame in beverages.[41]

Aspartame's major decomposition products are its cyclic dipeptide (in a 2,5-Diketopiperazine, or DKP, form), the non-esterified dipeptide (aspartylphenylalanine), and its constituent components, phenylalanine,[42] aspartic acid,[41] and methanol.[43] At 180 °C, aspartame undergoes decomposition to form a diketopiperazine derivative.[44]

Aspartate[]

Aspartic acid (aspartate) is one of the most common amino acids in the typical diet. As with methanol and phenylalanine, intake of aspartic acid from aspartame is less than would be expected from other dietary sources. At the 90th percentile of intake, aspartame provides only between 1% and 2% of the daily intake of aspartic acid. There has been some speculation[45][46] that aspartame, in conjunction with other amino acids like glutamate, may lead to excitotoxicity, inflicting damage on brain and nerve cells. However, clinical studies have shown no signs of neurotoxic effects,[7] and studies of metabolism suggest it is not possible to ingest enough aspartic acid and glutamate through food and drink to levels that would be expected to be toxic.[10]

Methanol[]

The methanol produced by the metabolism of aspartame is absorbed and quickly converted into formaldehyde and then completely oxidized to formic acid. The methanol from aspartame is unlikely to be a safety concern for several reasons. Fruit juices and citrus fruits contain methanol, and there are other dietary sources for methanol such as fermented beverages and the amount of methanol produced from aspartame-sweetened foods and beverages is likely to be less than that from these and other sources that are already in people's diets.[7] With regard to formaldehyde, it is rapidly converted in the body, and the amounts of formaldehyde from the metabolism of aspartame are trivial when compared to the amounts produced routinely by the human body and from other foods and drugs. At the highest expected human doses of consumption of aspartame, there are no increased blood levels of methanol or formic acid,[7] and ingesting aspartame at the 90th percentile of intake would produce 25 times less methanol than what would be considered toxic.[10]

Chemistry[]

Aspartame is a methyl ester of the dipeptide of the natural amino acids L-aspartic acid and L-phenylalanine.[3] Under strongly acidic or alkaline conditions, aspartame may generate methanol by hydrolysis. Under more severe conditions, the peptide bonds are also hydrolyzed, resulting in free amino acids.[47]

While known aspects of synthesis are covered by patents, many details are proprietary.[11] Two approaches to synthesis are used commercially. In the chemical synthesis, the two carboxyl groups of aspartic acid are joined into an anhydride, and the amino group is protected with a formyl group as the formamide, by treatment of aspartic acid with a mixture of formic acid and acetic anhydride.[48] Phenylalanine is converted to its methyl ester and combined with the N-formyl aspartic anhydride; then the protecting group is removed from aspartic nitrogen by acid hydrolysis. The drawback of this technique is that a byproduct, the bitter-tasting β-form, is produced when the wrong carboxyl group from aspartic acid anhydride links to phenylalanine, with desired and undesired isomer forming in a 4:1 ratio.[49] A process using an enzyme from Bacillus thermoproteolyticus to catalyze the condensation of the chemically altered amino acids will produce high yields without the β-form byproduct. A variant of this method, which has not been used commercially, uses unmodified aspartic acid, but produces low yields. Methods for directly producing aspartyl-phenylalanine by enzymatic means, followed by chemical methylation, have also been tried, but not scaled for industrial production.[50]

Intake[]

The acceptable daily intake (ADI) value for aspartame, as well as other food additives studied, is defined as the "amount of a food additive, expressed on a body weight basis, that can be ingested daily over a lifetime without appreciable health risk."[51] The Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) and the European Commission's Scientific Committee on Food has determined this value is 40 mg/kg of body weight for aspartame,[52] while FDA has set its ADI for aspartame at 50 mg/kg.[31]

The primary source for exposure to aspartame in the United States is diet soft drinks, though it can be consumed in other products, such as pharmaceutical preparations, fruit drinks, and chewing gum among others in smaller quantities.[7] A 12 US fluid ounce (355 ml) can of diet soda contains 0.18 grams (0.0063 oz) of aspartame, and for a 75 kg (165 lb) adult, it takes approximately 21 cans of diet soda daily to consume the 3.7 grams (0.13 oz) of aspartame that would surpass the FDA's 50 milligrams per kilogram of body weight ADI of aspartame from diet soda alone.[31]

Reviews have analyzed studies which have looked at the consumption of aspartame in countries worldwide, including the United States, countries in Europe, and Australia, among others. These reviews have found that even the high levels of intake of aspartame, studied across multiple countries and different methods of measuring aspartame consumption, are well below the ADI for safe consumption of aspartame.[7][8][52] Reviews have also found that populations that are believed to be especially high consumers of aspartame such as children and diabetics are below the ADI for safe consumption, even considering extreme worst-case scenario calculations of consumption.[7][8]

In a report released on 10 December 2013, the EFSA said that, after an extensive examination of evidence, it ruled out the "potential risk of aspartame causing damage to genes and inducing cancer," and deemed the amount found in diet sodas safe to consume.[53]

History[]

Aspartame was discovered in 1965 by James M. Schlatter, a chemist working for G.D. Searle & Company. Schlatter had synthesized aspartame as an intermediate step in generating a tetrapeptide of the hormone gastrin, for use in assessing an anti-ulcer drug candidate.[54] He discovered its sweet taste when he licked his finger, which had become contaminated with aspartame, to lift up a piece of paper.[7][55][56][57] Torunn Atteraas Garin participated in the development of aspartame as an artificial sweetener.[58]

In 1975, prompted by issues regarding Flagyl and Aldactone, a US FDA task force team reviewed 25 studies submitted by the manufacturer, including 11 on aspartame. The team reported "serious deficiencies in Searle's operations and practices".[4] The FDA sought to authenticate 15 of the submitted studies against the supporting data. In 1979, the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN) concluded, since many problems with the aspartame studies were minor and did not affect the conclusions, the studies could be used to assess aspartame's safety.[4]

In 1980, the FDA convened a Public Board of Inquiry (PBOI) consisting of independent advisors charged with examining the purported relationship between aspartame and brain cancer. The PBOI concluded aspartame does not cause brain damage, but it recommended against approving aspartame at that time, citing unanswered questions about cancer in laboratory rats.[4]:94–96[59]

In 1983, the FDA approved aspartame for use in carbonated beverages, and for use in other beverages, baked goods, and confections in 1993.[6] In 1996, the FDA removed all restrictions from aspartame, allowing it to be used in all foods.[6][60]

Several European Union countries approved aspartame in the 1980s, with EU-wide approval in 1994. The European Commission Scientific Committee on Food reviewed subsequent safety studies and reaffirmed the approval in 2002. The European Food Safety Authority reported in 2006 that the previously established Acceptable daily intake was appropriate, after reviewing yet another set of studies.[32]

Compendial status[]

- British Pharmacopoeia[61]

- United States Pharmacopeia[62]

Commercial uses[]

Under the trade names Equal, NutraSweet, and Canderel, aspartame is an ingredient in approximately 6,000 consumer foods and beverages sold worldwide, including (but not limited to) diet sodas and other soft drinks, instant breakfasts, breath mints, cereals, sugar-free chewing gum, cocoa mixes, frozen desserts, gelatin desserts, juices, laxatives, chewable vitamin supplements, milk drinks, pharmaceutical drugs and supplements, shake mixes, tabletop sweeteners, teas, instant coffees, topping mixes, wine coolers and yogurt. It is provided as a table condiment in some countries. Aspartame is less suitable for baking than other sweeteners, because it breaks down when heated and loses much of its sweetness.[63][64]

NutraSweet Company[]

In 1985, Monsanto Company bought G.D. Searle,[65] and the aspartame business became a separate Monsanto subsidiary, the NutraSweet Company. In March 2000, Monsanto sold it to J.W. Childs Equity Partners II L.P.[66] European use patents on aspartame expired starting in 1987,[67] and the US patent expired in 1992. Since then, the company has competed for market share with other manufacturers, including Ajinomoto, Merisant and the Holland Sweetener Company.

Ajinomoto[]

Many aspects of industrial synthesis of aspartame were established by Ajinomoto.[11] In 2004, the market for aspartame, in which Ajinomoto, the world's largest aspartame manufacturer, had a 40 percent share, was 14,000 metric tons a year, and consumption of the product was rising by 2 percent a year.[68] Ajinomoto acquired its aspartame business in 2000 from Monsanto for $67M.[69]

In 2008, Ajinomoto sued British supermarket chain Asda, part of Walmart, for a malicious falsehood action concerning its aspartame product when the substance was listed as excluded from the chain's product line, along with other "nasties". In July 2009, a British court found in favour of Asda.[70] In June 2010, an appeals court reversed the decision, allowing Ajinomoto to pursue a case against Asda to protect aspartame's reputation.[71] Asda said that it would continue to use the term "no nasties" on its own-label products,[72] but the suit was settled in 2011 with Asda choosing to remove references to aspartame from its packaging.[73]

In November 2009, Ajinomoto announced a new brand name for its aspartame sweetener – AminoSweet.[74]

Holland Sweetener Company[]

A joint venture of DSM and Tosoh, the Holland Sweetener Company manufactured aspartame using the enzymatic process developed by Toyo Soda (Tosoh) and sold as the brand Sanecta.[75] Additionally, they developed a combination aspartame-acesulfame salt under the brand name Twinsweet.[76] They left the sweetener industry in late 2006, because "global aspartame markets are facing structural oversupply, which has caused worldwide strong price erosion over the last five years", making the business "persistently unprofitable".[77]

Competing products[]

Because sucralose, unlike aspartame, retains its sweetness after being heated, and has at least twice the shelf life of aspartame, it has become more popular as an ingredient.[78] This, along with differences in marketing and changing consumer preferences, caused aspartame to lose market share to sucralose.[79][80] In 2004, aspartame traded at about $30/kg and sucralose, which is roughly three times sweeter by weight, at around $300/kg.[81]

See also[]

- Aspartame controversy

- Phenylalanine ammonia lyase

- Stevia

References[]

- ^ Budavari S, ed. (1989). "861. Aspartame". The Merck Index (11th ed.). Rahway, NJ: Merck & Co. p. 859. ISBN 978-0-911910-28-5.

- ^ Rowe RC (2009). "Aspartame". Handbook of Pharmaceutical Excipients. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-1-58212-058-4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Aspartame". PubChem, National Library of Medicine, US National Institutes of Health. 17 August 2019. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d US Government Accountability Office (17 July 1987). "US GAO – HRD-87-46 Food and Drug Administration: Food Additive Approval Process Followed for Aspartame, 18 June 1987" (HRD-87-46). Retrieved 5 September 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Mitchell H (2006). Sweeteners and sugar alternatives in food technology. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-4051-3434-7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "CFR – Code of Federal Regulations, Title 21, Part 172: Food additives permitted for direct addition to food for human consumption. Subpart I – Multipurpose Additives; Sec. 172.804 Aspartame". US Food and Drug Administration. 1 April 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Magnuson BA, Burdock GA, Doull J, Kroes RM, Marsh GM, Pariza MW, Spencer PS, Waddell WJ, Walker R, Williams GM (2007). "Aspartame: a safety evaluation based on current use levels, regulations, and toxicological and epidemiological studies". Critical Reviews in Toxicology. 37 (8): 629–727. doi:10.1080/10408440701516184. PMID 17828671. S2CID 7316097.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h EFSA National Experts (May 2010). "Report of the meetings on aspartame with national experts". EFSA Supporting Publications. EFSA. 7 (5). doi:10.2903/sp.efsa.2010.ZN-002. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Food Standards Australia New Zealand: "Food Standards Australia New Zealand: Aspartame – what it is and why it's used in our food". Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 9 December 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Butchko HH, Stargel WW, Comer CP, Mayhew DA, Benninger C, Blackburn GL, et al. (April 2002). "Aspartame: review of safety". Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 35 (2 Pt 2): S1–93. doi:10.1006/rtph.2002.1542. PMID 12180494.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c O'Donnell K (2006). "6 Aspartame and Neotame". In Mitchell HL (ed.). Sweeteners and sugar alternatives in food technology. Blackwell. pp. 86–95. ISBN 978-1-4051-3434-7. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- ^ "New Products Weigh In". foodproductdesign.com. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ^ "Fountain Beverages in the US" (PDF). The Coca-Cola Company. May 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2009.

- ^ Nahon DF, Roozen JP, de Graaf C (February 1998). "Sensory evaluation of mixtures of maltitol or aspartame, sucrose and an orange aroma". Chemical Senses. 23 (1): 59–66. doi:10.1093/chemse/23.1.59. PMID 9530970.

- ^ Mitchell H (2006). Sweeteners and sugar alternatives in food technology. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-4051-3434-7.

- ^ Henkel J (November–December 1999). Sugar substitutes. Americans opt for sweetness and lite. FDA Consumer. 33. Diane Publishing. pp. 12–16. ISBN 978-1-4223-2690-9. PMID 10628311. Archived from the original on 20 October 2016.

- ^ "Additional Information about High-Intensity Sweeteners Permitted for use in Food in the United States". FDA. US Food and Drug Administration. 8 February 2018. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "Aspartame". UK FSA. 17 June 2008. Archived from the original on 7 October 2010. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ^ "Aspartame". EFSA. Archived from the original on 10 March 2011. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ^ "Aspartame". Health Canada. 5 November 2002. Archived from the original on 22 September 2010. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ^ Azad MB, Abou-Setta AM, Chauhan BF, Rabbani R, Lys J, Copstein L, Mann A, Jeyaraman MM, Reid AE, Fiander M, MacKay DS, McGavock J, Wicklow B, Zarychanski R (July 2017). "Nonnutritive sweeteners and cardiometabolic health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies". CMAJ. 189 (28): E929–E939. doi:10.1503/cmaj.161390. PMC 5515645. PMID 28716847.

- ^ Rogers PJ, Hogenkamp PS, de Graaf C, Higgs S, Lluch A, Ness AR, Penfold C, Perry R, Putz P, Yeomans MR, Mela DJ (1 March 2016). "Does low-energy sweetener consumption affect energy intake and body weight? A systematic review, including meta-analyses, of the evidence from human and animal studies". International Journal of Obesity. 40 (3): 381–94. doi:10.1038/ijo.2015.177. PMC 4786736. PMID 26365102.

- ^ Miller PE, Perez V (September 2014). "Low-calorie sweeteners and body weight and composition: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 100 (3): 765–77. doi:10.3945/ajcn.113.082826. PMC 4135487. PMID 24944060.

- ^ Santos NC, de Araujo LM, De Luca Canto G, Guerra EN, Coelho MS, Borin MF (April 2017). "Metabolic effects of aspartame in adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 58 (12): 2068–81. doi:10.1080/10408398.2017.1304358. PMID 28394643. S2CID 43863824.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Phenylalanine". PubChem, National Library of Medicine, US National Institutes of Health. 17 August 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ^ "Aspartame". UK Food Standards Agency. 19 March 2015. Archived from the original on 11 July 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "Mandatory Labelling of Sweeteners". Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Health Canada. 11 May 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ^ Marinovich M, Galli CL, Bosetti C, Gallus S, La Vecchia C (October 2013). "Aspartame, low-calorie sweeteners and disease: regulatory safety and epidemiological issues". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 60: 109–15. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2013.07.040. PMID 23891579.

- ^ Kirkland D, Gatehouse D (October 2015). "Aspartame: A review of genotoxicity data". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 84: 161–68. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2015.08.021. PMID 26321723.

- ^ "US FDA/CFSAN – FDA Statement on European Aspartame Study". Archived from the original on 30 July 2010. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Aspartame and Cancer: Questions and Answers". National Cancer Institute. 12 September 2006. Archived from the original on 12 February 2009. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food (2006). "Opinion of the Scientific Panel on food additives, flavourings, processing aids and materials in contact with food (AFC) related to a new long-term carcinogenicity study on aspartame". The EFSA Journal. 356 (5): 1–44. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2006.356.

- ^ Lajtha A (1994). "Aspartame consumption: lack of effects on neural function". The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 5 (6): 266–83. doi:10.1016/0955-2863(94)90032-9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b ""Inactive" ingredients in pharmaceutical products: update (subject review). American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs". Pediatrics. 99 (2): 268–78. February 1997. doi:10.1542/peds.99.2.268. PMID 9024461.

- ^ Millichap JG, Yee MM (January 2003). "The diet factor in pediatric and adolescent migraine". Pediatric Neurology. 28 (1): 9–15. doi:10.1016/S0887-8994(02)00466-6. PMID 12657413.

- ^ Sun-Edelstein C, Mauskop A (June 2009). "Foods and supplements in the management of migraine headaches". The Clinical Journal of Pain. 25 (5): 446–52. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.530.1223. doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e31819a6f65. PMID 19454881. S2CID 3042635.

- ^ Li X, Staszewski L, Xu H, Durick K, Zoller M, Adler E (April 2002). "Human receptors for sweet and umami taste". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (7): 4692–96. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.4692L. doi:10.1073/pnas.072090199. PMC 123709. PMID 11917125.

- ^ Nelson, Greg; Chandrashekar, Jayaram; Hoon, Mark A.; Feng, Luxin; Zhao, Grace; Ryba, Nicholas J. P.; Zuker, Charles S. (March 2002). "An amino-acid taste receptor". Nature. 416 (6877): 199–202. Bibcode:2002Natur.416..199N. doi:10.1038/nature726. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 11894099. S2CID 1730089.

- ^ Roberts HJ (2004). "Aspartame disease: a possible cause for concomitant Graves' disease and pulmonary hypertension". Texas Heart Institute Journal. 31 (1): 105, author reply 105–06. PMC 387446. PMID 15061638.

- ^ Trocho C, Pardo R, Rafecas I, Virgili J, Remesar X, Fernández-López JA, Alemany M (1998). "Formaldehyde derived from dietary aspartame binds to tissue components in vivo". Life Sciences. 63 (5): 337–49. doi:10.1016/S0024-3205(98)00282-3. PMID 9714421.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stegink LD (July 1987). "The aspartame story: a model for the clinical testing of a food additive". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 46 (1 Suppl): 204–15. doi:10.1093/ajcn/46.1.204. PMID 3300262.

- ^ Prodolliet J, Bruelhart M (1993). "Determination of aspartame and its major decomposition products in foods". Journal of AOAC International. 76 (2): 275–82. doi:10.1093/jaoac/76.2.275. PMID 8471853.

- ^ Lin SY, Cheng YD (October 2000). "Simultaneous formation and detection of the reaction product of solid-state aspartame sweetener by FT-IR/DSC microscopic system". Food Additives and Contaminants. 17 (10): 821–27. doi:10.1080/026520300420385. PMID 11103265. S2CID 10065876.

- ^ Rastogi S, Zakrzewski M, Suryanarayanan R (March 2001). "Investigation of solid-state reactions using variable temperature X-ray powder diffractrometry. I. Aspartame hemihydrate". Pharmaceutical Research. 18 (3): 267–73. doi:10.1023/A:1011086409967. PMID 11442263. S2CID 8736945.

- ^ Olney JW (1984). "Excitotoxic food additives--relevance of animal studies to human safety". Neurobehavioral Toxicology and Teratology. 6 (6): 455–62. PMID 6152304.

- ^ Rycerz K, Jaworska-Adamu JE (2013). "Effects of aspartame metabolites on astrocytes and neurons". Folia Neuropathologica. 51 (1): 10–17. doi:10.5114/fn.2013.34191. PMID 23553132.

- ^ Ager DJ, Pantaleone DP, Henderson SA, Katritzky AR, Prakash I, Walters DE (1998). "Commercial, Synthetic Non-nutritive Sweeteners". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 37 (13–24): 1802–17. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980803)37:13/14<1802::AID-ANIE1802>3.0.CO;2-9.

- ^ US 20040137559A, "Process for producing N-formylamino acid and use thereof", issued 2003-10-20

- ^ "The Saccharin Saga – Part 6 :: ChemViews Magazine :: ChemistryViews". chemistryviews.org. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ^ Yagasaki M, Hashimoto S (November 2008). "Synthesis and application of dipeptides; current status and perspectives". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 81 (1): 13–22. doi:10.1007/s00253-008-1590-3. PMID 18795289. S2CID 10200090.

- ^ WHO (1987). "Principles for the safety assessment of food additives and contaminants in food". Environmental Health Criteria 70. Archived from the original on 30 April 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Renwick AG (April 2006). "The intake of intense sweeteners – an update review". Food Additives and Contaminants. 23 (4): 327–38. doi:10.1080/02652030500442532. PMID 16546879. S2CID 27351427.

- ^ "Aspartame in Soda is Safe: European Review". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 17 December 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- ^ Mazur RH (1974). "Aspartic acid-based sweeteners". In Inglett GE (ed.). Symposium: sweeteners. Westport, CT: AVI Publishing. pp. 159–63. ISBN 978-0-87055-153-6. LCCN 73-94092.

- ^ Lewis R (2001). Discovery: windows on the life sciences. Oxford: Blackwell Science. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-632-04452-8.

- ^ Mazur, R.H. (1984). "Discovery of aspartame". In Aspartame: Physiology and Biochemistry. L. D. Stegink and L. J. Filer Jr. (Eds.). Marcel Dekker, New York, pp. 3–9.

- ^ Mills, Judy (21 September 1983). "Aspartame: The controversy continues despite FDA blessings". Spokane Chronicle. (Washington). p. B1.

- ^ "Torunn A. Garin, 54, Noted Food Engineer". The New York Times. 1 May 2002. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016.

- ^ Testimony of Dr. Adrian Gross, Former FDA Investigator to the US Senate Committee on Labor and Human Resources, 3 November 1987. Hearing title: "NutraSweet Health and Safety Concerns." Document # Y 4.L 11/4:S.HR6.100, pp. 430–39.

- ^ FDA Statement on Aspartame, 18 November 1996

- ^ British Pharmacopoeia Commission Secretariat. "Index (BP)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2009. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

- ^ United States Pharmacopeia. "Food Ingredient Reference Standards" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2010. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

- ^ "How Sugar Substitutes Stack Up". National Geographic News. 17 July 2013. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- ^ Struck, Susanne; Jaros, Doris; Brennan, Charles S.; Rohm, Harald (2014). "Sugar replacement in sweetened bakery goods". International Journal of Food Science & Technology. 49 (9): 1963–76. doi:10.1111/ijfs.12617.

- ^ Greenhouse, Steven (18 July 1985). "Monsanto to Acquire G.D. Searle". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 November 2017.

- ^ J.W. Childs Equity Partners II, L.P Archived 14 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Food & Drink Weekly, 5 June 2000

- ^ Shapiro E (19 November 1989). "Nutrasweet's Bitter Fight". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 February 2017.

- ^ "Ajinomoto May Exceed Full-Year Forecasts on Amino Acid Products – Bloomberg". Bloomberg. 18 November 2004. Archived from the original on 20 June 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- ^ "Sweetener sale-05/06/2000-ECN". icis.com. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ "Asda claims victory in aspartame 'nasty' case". foodanddrinkeurope.com. Archived from the original on 3 January 2010. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- ^ "FoodBev.com". foodbev.com. 3 June 2010. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

Court of Appeal rules in Ajinomoto/Asda aspartame case

- ^ "Radical new twist in Ajinomoto vs Asda 'nasty' battle". foodnavigator.com. Archived from the original on 6 June 2010. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- ^ Bouckley B (18 May 2011). "Asda settles 'nasty' aspartame legal battle with Ajinomoto". William Reed Business Media SAS. FoodNavigator.com. Archived from the original on 31 July 2011. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- ^ "Ajinomoto brands aspartame AminoSweet". Foodnavigator.com. 25 November 2009. Archived from the original on 30 August 2010. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- "Ajinomoto brands aspartame 'AminoSweet'". FoodBev.com. 17 November 2009. Archived from the original on 30 March 2010. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- ^ Lee TD (2007). "Sweetners". Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. 24 (5th ed.). Wiley. pp. 224–52. doi:10.1002/0471238961.19230505120505.a01.pub2. ISBN 978-0-471-48496-7.

- ^ "Holland Sweetener rolls out Twinsweet". BakeryAndSnacks.com. William Reed Business Media. 19 November 2003. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ^ "Holland Sweetener Company to exit from aspartame business" Archived 7 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. DSM press release, US Securities and Exchange Commission. 30 March 2006.

- ^ Warner M (22 December 2004). "A Something Among the Sweet Nothings; Splenda Is Leaving Other Sugar Substitutes With That Empty Feeling". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 21 April 2017.

- ^ John Schmeltzer (2 December 2004). "Equal fights to get even as Splenda looks sweet". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 4 December 2010. Retrieved 4 July 2007.

- ^ Carney, Beth (19 January 2005). "It's Not All Sweetness for Splenda". BusinessWeek: Daily Briefing. Archived from the original on 7 October 2008. Retrieved 5 September 2008.

- ^ "Aspartame defence courts reaction". beveragedaily.com. 7 October 2004. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011.

External links[]

Media related to Aspartame at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Aspartame at Wikimedia Commons

- Amino acid derivatives

- Aromatic compounds

- Butyramides

- Dipeptides

- Carboxylate esters

- Sugar substitutes

- Methyl esters

- E-number additives