Atonement (2007 film)

| Atonement | |

|---|---|

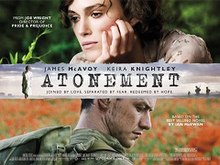

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Joe Wright |

| Screenplay by | Christopher Hampton |

| Based on | Atonement by Ian McEwan |

| Produced by | |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Seamus McGarvey |

| Edited by | Paul Tothill |

| Music by | Dario Marianelli |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | StudioCanal (France)[2] Universal Pictures (United Kingdom and Germany)[2] |

Release date |

|

Running time | 123 minutes[3] |

| Countries | |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £23.2 million ($30 million)[6] |

| Box office | $131 million[2] |

Atonement is a 2007 romantic war drama film directed by Joe Wright and starring James McAvoy, Keira Knightley, Saoirse Ronan, Romola Garai, Benedict Cumberbatch and Vanessa Redgrave. It is based on Ian McEwan's 2001 novel of the same name. The film chronicles a crime and its consequences over the course of six decades, beginning in the 1930s. It was produced for StudioCanal and filmed in England. Distributed in most of the world by Universal Studios, it was released in the United Kingdom and Ireland on 7 September 2007 and in North America on 7 December 2007.

Atonement opened both the 2007 Vancouver International Film Festival and the 64th Venice International Film Festival, making Wright, at the age of 35, the youngest director ever to open the latter event. The film was a commercial success and earned a worldwide gross of approximately $129 million against a budget of $30 million. Critics gave the drama positive reviews, praising its acting performances, direction, emotion, Dario Marianelli's score, its cinematography and visuals.

Atonement won an Oscar for Best Original Score at the 80th Academy Awards and was nominated for six others, including Best Picture, Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Supporting Actress for Ronan.[7] It also garnered fourteen nominations at the 61st British Academy Film Awards, winning both Best Film and Production Design, and won the Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Drama.[8]

Plot[]

In 1935 England, 13-year-old Briony Tallis, the youngest daughter of the wealthy Tallis family, is set to perform a play she has written for an upcoming family gathering. Looking out of her bedroom window, she spies on her older sister, Cecilia, and the housekeeper's son, Robbie Turner, on whom Briony has a crush. During their argument near the fountain, Robbie accidentally breaks a vase and yells at Cecilia to stay where she is – so as to avoid cutting her feet on the broken pieces on the ground. Still angered, Cecilia then strips off her outer clothing, stares at him and climbs into the basin to retrieve one of the pieces. Briony misinterprets the scene as Robbie ordering her sister to undress and get in the water.

Robbie drafts a note to Cecilia to apologise for the incident. In one draft, designed only as a private joke, he confesses his sexual attraction to her in explicit terms. He then writes a more formal letter and gives it to Briony to deliver. Only afterwards does he realise he has given her the wrong letter. Briony reads the letter before giving it to Cecilia. Later, she describes it to her 15-year-old visiting cousin, Lola, who calls Robbie a "sex maniac". Paul Marshall, a visiting friend of Briony's older brother, introduces himself to the visiting cousins and appears to be attracted to Lola. Before dinner, Robbie apologises to Cecilia for the obscene letter but, to his surprise, she confesses her secret love for him. They proceed to make passionate love in the library. Briony walks in on them and thinks that Robbie is raping Cecilia.

At dinner, Lola's twin brothers go missing and a search is organised. Outside in the dark, Briony sees Lola apparently being raped by a man, who flees upon being discovered. The two girls talk and Briony becomes convinced that it was Robbie again. A confused Lola does not dissent. Robbie finds the twins and returns with them. On the basis of Lola and Briony's testimony, and the explicit letter Robbie wrote to Cecilia, he is arrested for the rape.

Four years later, during the Second World War, Robbie has been released from prison on the condition that he joins the army and fights in the Battle of France. Separated from his unit, he makes his way on foot to Dunkirk. He thinks back to six months earlier when he met Cecilia, now a nurse. Briony, now 18, has chosen to join Cecilia's old nursing unit at St Thomas' Hospital in London rather than go to the University of Cambridge. She writes to her sister, but Cecilia has not forgiven her for her part in the investigation and conviction years before. Robbie, who is falling gravely ill from an infected wound, finally arrives at the beaches of Dunkirk, where he waits to be evacuated.

Later, Briony, who now regrets implicating Robbie, learns from a newsreel that Paul Marshall, who now owns a factory supplying rations to the British army, is about to marry Lola. Briony goes to the ceremony and she realises that it was Paul who assaulted Lola. Briony goes to visit Cecilia to apologise directly, and suggests correcting her testimony to which Cecilia says she would be an "unreliable witness". Briony is surprised to find Robbie there living with her sister, while in London on leave. Briony apologises for her deceit, but Robbie is enraged that she has still not accepted responsibility for her actions. Cecilia calms him down and then Robbie instructs Briony how to correct the record and get Robbie's conviction overturned. Briony agrees. Cecilia adds that Briony include what she remembers of Danny Hardman, but Briony points out that Paul Marshall was the rapist and Cecilia adds he has just married Lola and now Lola will not be able to testify against her husband.

Decades later, Briony is an elderly and successful novelist, giving an interview about her latest and last book, an autobiographical novel titled Atonement, as she is dying from Vascular dementia. She confesses that the scene in the book describing her visit and apology to Cecilia and Robbie was entirely imaginary. Cecilia and Robbie were never reunited: Robbie died of septicaemia at Dunkirk on the morning of the day he was to be evacuated and Cecilia died months later in the Balham tube station bombing during the Blitz. Briony hopes to give the two, in fiction, the happiness that she robbed them of in real life. The last scene shows an imagined, happily reunited Cecilia and Robbie staying in the house by the sea which they had intended to visit once they were reunited.

Cast[]

- James McAvoy as Robbie Turner, the son of the Tallis family housekeeper with a Cambridge education courtesy of his mother's employer.

- Keira Knightley as Cecilia Tallis, the elder of the two Tallis sisters.

- Saoirse Ronan as Briony Tallis, aged 13; the younger Tallis sister and an aspiring novelist.

- Romola Garai as Briony, aged 18.

- Vanessa Redgrave as older Briony, now a successful novelist.

- Brenda Blethyn as Grace Turner, Robbie's mother and the Tallis family housekeeper.

- Juno Temple as Lola Quincey, the visiting 15-year-old cousin of the Tallis siblings.

- Benedict Cumberbatch as Paul Marshall, Leon Tallis's visiting friend.

- Patrick Kennedy as Leon Tallis, the eldest of the Tallis siblings.

- Harriet Walter as Emily Tallis, the matriarch of the family.

- Peter Wight as Police Inspector.

- Daniel Mays as Tommy Nettle, one of Robbie's brothers-in-arms.

- Nonso Anozie as Frank Mace, another fellow soldier.

- Gina McKee as Sister Drummond.

- Jérémie Renier as Luc Cornet, a fatally wounded and brain-damaged French soldier whom the 18-year-old Briony comforts on his deathbed.

- Michelle Duncan as Fiona Maguire, Briony's nursing friend at St Thomas' Hospital.

- Alfie Allen as Danny Hardman, a worker on the Tallis estate who is falsely accused of rape.

In addition, film director and playwright Anthony Minghella briefly appears as the television interviewer in the final scene. Minghella died six months after the film was released, aged 54, following cancer surgery.

Production[]

Pre-production[]

Director Joe Wright asked executive producers, Debra Hayward, Liza Chasin, and co-producer Jane Frazer to collaborate a second time, after working on Pride and Prejudice in 2005, as well as production designer Sarah Greenwood, editor Paul Tothill, with costume designer Jacqueline Durran and composer Dario Marianelli, who have all previously worked together with Wright. In an interview, Wright states, "It's important for me to work with the same people. It makes me feel safe, and we kind of understand each other."[9] The screenplay was adapted from Ian McEwan's 2001 novel by Christopher Hampton.[10]

After reading McEwan's book, Hampton, who had previously undertaken many adaptations, was inspired to adapt it into a script for a feature film.[11] When Wright took over the project as director, he decided he wanted a different approach, and Hampton re-wrote much of his original script to Wright's suggestion. The first draft – written with director Richard Eyre in mind – took what Hampton called a more "conventional, literary approach", with a linear structure, and a voiceover and the epilogue of the older Briony being woven in throughout the entire film instead of only at the end. Wright felt that the original approach owed more to contemporary filmmaking than historical filmmaking. The second script was closer to the book.[11][12]

To re-create the Second World War setting, a historian was employed to work with the department heads. Background research involved the examination of paintings, photographs and films, and the study of archives.[12] The war scenes, like many others, were filmed on location in a seaside town. Set decorator, Katie Spencer and production designer, Sarah Greenwood, both visited archives from Country Life in search of finding suitable locations for their initial creative ideas for the interior and exterior scenes.[12] Seamus McGarvey, the cinematographer, worked closely with Wright on the aesthetics of the visualisation, using a range of techniques and camera movements to achieve the final result.

Casting[]

For Wright, casting became a lengthy process, particularly choosing the right actors for his protagonists. Having previously worked with Keira Knightley on Pride and Prejudice, he expressed his admiration for her, stating, "I think she's a really extraordinary actress".[13] Particularly in reference to the character's unlikeability, Wright commended her bravery in tackling this type of role without any fear of how the audience will receive this characterisation, stating "It's a character that's not always likeable and I think so many young actors these days are terrified of being disliked at any given moment in case the audience doesn't come and pay their box-office money to see them again. Keira is not afraid of that. She puts her craft first."[13] As opposed to casting McAvoy, "Knightley was in almost the opposite position—that of a sexy, beautiful movie star who, despite having worked steadily since she was seven, was widely underestimated as an actress."[14] In preparation for her role, Knightley watched films from the 1930s and 1940s, such as Brief Encounter and In Which We Serve, to study the "naturalism" of the performance that Wright wanted in Atonement.[15]

James McAvoy, despite turning down previous offers to work with Wright, nonetheless remained the director's first choice. Producers met several actors for the role, but McAvoy was the only one offered the part. He fitted Wright's bid for someone who "had the acting ability to take the audience with him on his personal and physical journey". McAvoy describes Robbie as one of the most difficult characters he has ever played, "because he's very straight-ahead".[15] Further describing his casting process, Wright commented how "there is something undeniably charming about McAvoy".[16] One of the most important qualities that particularly resonated with Wright was "McAvoy's own working-class roots",[16] which McAvoy noted was something that Wright was very much interested in. Once Wright put both Knightley and McAvoy together, their "palpable sexual chemistry"[14] immediately became apparent. The biggest risk Wright took in casting McAvoy was that "The real question was whether the five-foot-seven, slightly built, ghostly pale Scotsman had what it takes to be a true screen idol."[14]

In addition, the casting of Briony Tallis also proved challenging, yet once Wright discovered Saoirse Ronan her involvement enabled Wright to finally commence filming. On the casting process for this particular role, Wright commented how "We met many, many kids for that role. Then we were sent this tape of this little girl speaking in this perfect 1920s English accent. Immediately, she had this kind of intensity, dynamism, and willfulness."[17] After inviting Ronan to come to London to read for the part, Wright was not only surprised by her Irish accent, but immediately recognised her unique acting ability.[17] Upon casting Ronan, Wright revealed how completing this final casting decision enabled "the film to be what it became" and considered her participation in the film "lucky".[18]

Abbie Cornish was pegged for the role of 18-year-old Briony,[19] but had to back out due to scheduling conflicts with Elizabeth: The Golden Age.[20] Romola Garai was cast instead, and was obliged to adapt her performance's physicality to fit the appearance that had already been decided upon for Ronan and Redgrave. Garai spent much time with Ronan, and watched footage of her to approximate the way the younger actress moved.[15] Vanessa Redgrave became everyone's ideal to play the oldest Briony[15] and was the first approached (although she was not cast until Ronan had been found),[21] and committed herself to the role after just one meeting with Wright. She, Ronan and Garai worked together with a voice coach to keep the character's timbre in a familiar range throughout the film.[15]

Filming[]

The film was produced by StudioCanal and filmed throughout the summer of 2006 in Great Britain.[22]

Due to restrictions in the filming schedule which meant that production only had two full days to film all the needed scenes of the war front on Dunkirk beach, and the lack of budget to fund the 1000+ extras needed for the shooting of these scenes, Joe Wright and cinematographer Seamus McGarvey were forced to reduce the shooting down into a 5½ minute long-take following James McAvoy's character as he moved a quarter of a mile along the beach.

The first of the two days, and part of the second day, were dedicated to blocking and rehearsing the sequence until the sun was in the correct position in the afternoon ready to shoot. The shot took 3½ takes. The fourth was abandoned mid-flow due to the lighting becoming too bad for shooting. They ended up using the third take. The sequence was accomplished by Steadicam operator, Peter Robertson, moving from a tracking vehicle, to on foot, to a rickshaw via a ramp and back to on foot.[23][24]

Locations[]

These mainly were:

- Stokesay Court, Onibury, Shropshire.[25][26][27]

- The seafront in Redcar.[28][29] This work included an acclaimed five-minute tracking shot of the seafront as a war-torn Dunkirk and a scene in the local cinema on the promenade.[30][31]

- Dunkirk street scenes were shot at the Grimsby ice factory on Grimsby Docks, interior and exterior.

- Streatham Hill, London (for neighbouring Balham, Cecilia's new home after breaking with her family).

The other places across London were Great Scotland Yard and Bethnal Green Town Hall, the latter being used for a 1939 tea-house scene, as well as the church of St John's, Smith Square, Westminster for Lola's wedding. Re-enactment of the 1940 Balham station disaster took place in the former Piccadilly line station of Aldwych, closed since the 1990s.

War scenes (in the French countryside) were filmed in Coates and Gedney Drove End, Lincolnshire; Walpole St Andrew and Denver, Norfolk; and in Manea and Pymoor, Cambridgeshire.

Much of the St Thomas's hospital ward interior was filmed at Park Place, Berkshire and exterior at University College London.[30]

All the exteriors and interiors of the Tallis family home were filmed at Stokesay Court, selected from an old Country Life edition to tie in with the period and pool fountain of the novel.[32] This mansion was built in 1889 commissioned by the glove manufacturer John Derby Allcroft. It remains an undivided family home.

The third portion of Atonement was entirely filmed at the BBC Television Centre, London. The beach with cliffs first shown on the postcard and later seen towards the end of the film was Cuckmere Haven Seven Sisters, Sussex (near Roedean School, which Cecilia was said to have attended).

Release[]

Theatrical[]

The film opened at the 2007 Venice International Film Festival, making Wright, at 35, the youngest director ever to be so honoured.[33] The film also opened at the 2007 Vancouver International Film Festival.[34] Atonement was released in the United Kingdom and Ireland on 7 September 2007, and in North America on 7 December 2007.[35] Along with a worldwide theatrical distribution which was managed by Universal Pictures, with minor releases through other divisions on 7 September 2007.[36]

Home media[]

Atonement was released on DVD in the US on 3 January 2008 in region 2, and followed a release in Blu-ray edition on 13 March 2012.[37] The film followed a DVD release on 4 February 2010 on Amazon in the UK and in Blu-ray with a release on 27 May 2010.[38]

Reception[]

Box office[]

The film grossed a cumulative $131,016,624 worldwide and in opening weekend in USA, $784,145, 9 December 2007 with a budget to make the film of $30,000,000 (estimated).[39] A total gross of $23,934,714 (worldwide) and with the release in the US a total gross of $50,927,067.[40]

Critical response[]

The film received positive reviews from film critics. The review site Rotten Tomatoes records that 83% of 219 critics gave the film positive reviews, with an average rating of 7.5/10. The consensus reads, "Atonement features strong performances, brilliant cinematography and a unique score. Featuring deft performances from James McAvoy and Keira Knightley, it's a successful adaptation of Ian McEwan's novel."[41] On other review sites, Metacritic records an average score of 85%, based on 36 reviews.[42]

In Britain, the film was listed as #3 on Empire's Top 25 Films of 2007. The American critic Roger Ebert gave it a four-star review, dubbing it "one of the year's best films, a certain best picture nominee".[43] In the film review television program, At the Movies with Ebert & Roeper, Richard Roeper gave the film a "thumbs up", adding that Knightley gave "one of her best performances". As for the film, he commented that "Atonement has hints of greatness but it falls just short of Oscar contention".[44] The film received near-unanimous praise on its release, with its casting solidifying Knightley as a leading star in British period dramas while igniting McAvoy's career in leading roles. Most importantly, it catapulted the trajectory of a young Ronan. Upon its release, The Daily Telegraph's David Gritten describes how "Critics who have seen Atonement have reacted with breathless superlatives, and its showing at Venice and subsequent release will almost certainly catapult Wright into the ranks of world-class film directors."[45] The film received many positive reviews for its adherence to McEwan's novel, with Variety reporting that the film "preserves much of the tome's metaphysical depth and all of its emotional power", and commenting that "Atonement is immensely faithful to McEwan's novel."[46] Author Ian McEwan also worked as an executive producer on the film.[47]

However, not all reviews were as favourable. Although The Atlantic's Christopher Orr praises Knightley's performance as "strong" and McAvoy as "likeable and magnetic", he concludes by saying "Atonement is a film out of balance, nimble enough in its first half but oddly scattered and ungainly once it leaves the grounds of the Tallis estate", and remains "a workmanlike yet vaguely disappointing adaptation of a masterful novel".[48] The New York Times' A. O. Scott comes to a similar conclusion, saying "Mr McAvoy and Ms Knightley sigh and swoon credibly enough, but they are stymied by the inertia of the filmmaking, and by the film's failure to find a strong connection between the fates of the characters and the ideas and historical events that swirl around them."[49]

On a more positive note, The New York Observer's Rex Reed considers Atonement his "favorite film of the year", deeming it "everything a true lover of literature and movies could possibly hope for", and particularly singling out McAvoy as "the film's star in an honest, heart-rending performance of strength and integrity that overcomes the romantic slush it might have been", and praising Ronan as a "staggeringly assured youngster", while being underwhelmed by a "serenely bland Keira Knightley".[50] Adding to the film's authentic adaptation, David Gritten once again notes how "If Atonement feels like a triumph, it's a totally British one."[45] McAvoy is singled out: "His performance as Robbie Turner, the son of a housekeeper at a country estate, raised with ambitions but appallingly wronged, holds the movie together."[16]

Top ten lists[]

The film appeared on many critics' top ten lists of the best films of 2007.[51]

| Rank | Critic | Publication |

|---|---|---|

| 1st | Kenneth Turan | Los Angeles Times |

| 1st | Lou Lumenick | New York Post |

| 2nd | Peter Travers | Rolling Stone[52] |

| 3rd | N/A | Empire |

| 4th | Ann Hornaday | The Washington Post |

| 4th | Joe Morgenstern | The Wall Street Journal |

| 4th | Richard Corliss | Time |

| 4th | Roger Ebert | Chicago Sun-Times |

| 4th | Tasha Robinson | The A.V. Club |

| 7th | Nathan Rabin | The A.V. Club |

| 8th | James Berardinelli | ReelViews |

| 8th | Keith Phipps | The A.V. Club |

| 8th | Stephen Holden | The New York Times |

| 9th | Marjorie Baumgarten | The Austin Chronicle |

| 10th | Michael Sragow | The Baltimore Sun |

| 10th | Noel Murray | The A.V. Club |

Accolades[]

The film has received numerous awards and nominations, including seven Golden Globe nominations, more than any other film nominated at the 65th Golden Globe Awards,[53][54] and winning two of the nominated Golden Globes, including Best Motion Picture Drama. The film also received 14 BAFTA nominations for the 61st British Academy Film Awards including Best Film, Best British Film and Best Director,[55] seven Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture,[56] and the Evening Standard British Film Award for Technical Achievement in Cinematography, Production Design and Costume Design, earned by Seamus McGarvey, Sarah Greenwood and Jacqueline Durran, respectively. Atonement also ranks 442nd on Empire magazine's 2008 list of the 500 greatest movies of all time.[57]

Atonement has been named among the Top 10 Films of 2007 by the Austin Film Critics Association,[58] the Dallas-Fort Worth Film Critics Association, New York Film Critics Online[59] and the Southeastern Film Critics Association.[60]

Cultural impact[]

The green dress Keira Knightley's character wears during the love scene in the library garnered considerable interest.[61][62] At the ten-year anniversary of the film's American premiere, the film's costume designer Jacqueline Durran called it "unforgettable".[63]

Historical inaccuracies[]

The film shows an Avro Lancaster bomber flying overhead in 1935, an aircraft whose first flight was not until 1941.[64]

During the scene in 1935 in which Robbie writes and discards letters for Cecilia, he keeps playing a record of the love duet from Act 1 of La bohème, with Victoria de los Ángeles and Jussi Björling singing, which was not recorded until 1956.[65]

In the scene on the Dunkirk beach, Robbie is told that the Lancastria has been sunk, an event that actually happened two weeks after the Dunkirk evacuations.[66]

In the final scene, Briony states that the deadly flooding of Balham tube station, whilst it was being used as an overnight air-raid shelter, occurred on 15 October 1940. However, the flooding actually occurred before midnight, when the date was still 14 October.[67]

See also[]

- Atonement (soundtrack)

References[]

- ^ "Atonement (2007) - Financial Information". The Numbers. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c N.a. "Atonement - Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 6 June 2019. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ^ "ATONEMENT (15)". Universal Studios. British Board of Film Classification. 10 July 2007. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Atonement (2007)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 19 September 2018. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- ^ "LUMIERE : Film: Atonement". Lumiere. Archived from the original on 23 February 2019. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- ^ Gritten, David. "Joe Wright: 'I said I needed $4m more for Dunkirk, they said no'". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 25 September 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ^ "Academy Award nominations for 'Atonement'". Oscar.com. 23 January 2008. Archived from the original on 29 January 2008. Retrieved 24 January 2008.

- ^ "BAFTA Awards for 'Atonement'". BAFTA.org. 10 February 2008. Archived from the original on 11 February 2008. Retrieved 10 February 2008.

- ^ Douglas, Edward. "Joe Wright on Directing Atonement". Comingsoon.net. Archived from the original on 13 December 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ McFarlane, B (2008). "Watching, Writing and control: Atonement". Screen Education.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hampton, Christopher. "Atonement, so good I adapted it twice". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c n.a. "Production Notes - Atonement". Focus Features. Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Staff, Indy. "Sitting Down with Joe Wright, Director of Atonement". Santa Barbara Independent. Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Comita, Jenny. "Keira & James". W Magazine. Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Behind-the-Scenes of Atonement". WildAboutMovies.com. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Addley, Esther. "I feel on the edge of failure". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sperling, Nicole. "Director Joe Wright on Discovering Saoirse Ronan and Getting Gary Oldman to Become Churchill". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on 24 December 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ Stolworthy, Jacob. "Darkest Hour director Joe Wright shares candid thoughts on each of his films: 'I had a breakdown after making Atonement'". Independent. Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 September 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 September 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ n.a. "A Modern Version of that Stiff Upper Lip". Close-UpFilm.com. Archived from the original on 26 December 2007. Retrieved 4 January 2008.

- ^ "Atonement (2007)" Archived 22 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine. IMDb. Amazon.com. Retrieved 22 November 2011.[better source needed]

- ^ Witmer, Jon D. "Atonement, shot by Seamus McGarvey, BSC, lends stunning visuals to a novel's impact". The ASC. Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ Fredrick, David J. "SOC 2013 - Peter Robertson, ACO, SOC - Atonement Hist Shot Award". Vimeo. Archived from the original on 4 October 2015. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ "Atonement". The Castles and Manor Houses of Cinema's Greatest Period Films. Architectural Digest. January 2013. Archived from the original on 18 January 2013. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ^ "Atonement". The Castles and Manor Houses of Cinema's Greatest Period Films. Architectural Digest. January 2013. Archived from the original on 18 January 2013. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ^ Gritten, David (24 August 2007). "Joe Wright: a new movie master". Telegraph.co.uk. London. Archived from the original on 14 October 2007. Retrieved 24 August 2007.

- ^ "Filming locations for 'Atonement' (2007)" Archived 15 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. IMDb. Amazon.com. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ^ Hencke, David (24 May 2006). "Redcar scrubs up for starring role". Guardian.co.uk. London. Archived from the original on 16 August 2007. Retrieved 17 July 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Behind-the-Scenes of 'Atonement'". WildAboutMovies.com. Archived from the original on 29 December 2007. Retrieved 4 January 2008.

- ^ Wloszczyna, Susan (19 December 2007). "5 1/2-minute tracking shot dazzles in 'Atonement'". USA Today. Archived from the original on 12 August 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ^ Conway Morris, Roderick (30 August 2007). "Review: 'Atonement' and 'Se, jie' at Venice festival: Love and lust in wartime". International Herald Tribune (IHT). Archived from the original on 27 January 2008. Retrieved 1 September 2007.

- ^ Gritten, David. "Joe Wright: A New Movie Master". Telegraph. Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ n.a. "Atonement to launch Vancouver International Film Festival". CBC News. Archived from the original on 26 January 2008. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ n.a. "Atonement - Keira Knightley & James McAvoy". Stokesay Court. Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ n.a. "Atonement 2007". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ n.a. "Atonement (2007)". DVDs Release Date. Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ n.a. "Atonement [DVD] [2007]". Amazon. Archived from the original on 7 September 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ n.a. "Atonement (2007)". Internet Movie Database (IMDb). Archived from the original on 6 March 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ n.a. "Atonement". Box Office Mojo by IMDb Pro. Archived from the original on 6 June 2019. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ "Atonement". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ n.a. "Atonement". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 17 April 2010. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "Atonement". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 7 June 2013. Retrieved 28 December 2007.

- ^ Roeper, Richard. "Atonement Reviews". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 14 January 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gritten, David. "Joe Wright: a new movie master". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ Geraghty, C (2009). Foregrounding the Media: Atonement (2007) as an adaptation. Oxford Academic.

- ^ McGrath, C. "'Atonement': Adapting a literary device to the big screen". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- ^ Orr, Christopher. "The Movie Review: 'Atonement'". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 15 December 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ Scott, A.O. "Lies, Guilt, Stiff Upper Lips". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 October 2019. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ Reed, Rex. "Atonement Is My Favorite of the Year!". The Observer. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ "Metacritic: 2007 Film Critic Top Ten Lists". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 2 January 2008. Retrieved 5 January 2008.

- ^ Travers, Peter. (19 December 2007). "Peter Travers' Best and Worst Movies of 2007" Archived 21 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine. RollingStone.com. Retrieved 20 December 2007.

- ^ n.a. "Atonement leads field at Globes". BBC News. Archived from the original on 15 December 2007. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ^ n.a. "Atonement". Golden Globes. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ n.a. "BAFTA Awards Search". BAFTA. Archived from the original on 7 September 2020. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ n.a. "THE 80TH ACADEMY AWARDS 2008". Oscars. Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ Green, Willow. "The 500 Greatest Movies Of All Time". Empire. Archived from the original on 4 November 2015. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ Austin Film Critics. "2007 Awards". Austin Film Critics Association. Archived from the original on 7 September 2020. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ Douglas, Edward. "NYFCO (New York Film Critics Online) Loves Blood !". ComingSoon.net. Archived from the original on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ n.a. "Winners". SEFCA. Archived from the original on 6 December 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 16 May 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 11 December 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 15 June 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Holmes, H. (2002). "Avro Lancaster" (Aviators Database).

- ^ Greenfield, Edward. "La Boheme". In: Opera on Record, ed. Blyth, Alan. Hutchinson & Co, 1979, p. 589.

- ^ Fenby, Jonathan (2015). The Sinking of the Lancastria: Britain's greatest maritime disaster and Churchill's cover up. London: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0743259309.

- ^ Miller, J. Hillis (2013). "Some versions of romance trauma as generated by realist detail in Ian McEwan's Atonement". In Ganteau, Jean-Michel; Onega, Susana (eds.). Trauma and Romance in Contemporary British Literature. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780203073766.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Atonement (2007 film) |

- 2007 films

- English-language films

- 2007 romantic drama films

- 2000s war drama films

- BAFTA winners (films)

- Best Drama Picture Golden Globe winners

- Best Film BAFTA Award winners

- British films

- British romantic drama films

- British war drama films

- Dunkirk evacuation films

- Fiction with unreliable narrators

- Films scored by Dario Marianelli

- Films about atonement

- Films about writers

- Films based on British novels

- Films directed by Joe Wright

- Films produced by Tim Bevan

- Films produced by Eric Fellner

- Films about the upper class

- Films set in the 1930s

- Films set in the 1940s

- Films set in country houses

- Films set in England

- Films set in France

- Films shot in Berkshire

- Films shot in Cambridgeshire

- Films shot in East Sussex

- Films shot in Lincolnshire

- Films shot in London

- Films shot in Norfolk

- Films shot in North Yorkshire

- Films shot in Shropshire

- Films that won the Best Original Score Academy Award

- British historical romance films

- British nonlinear narrative films

- French nonlinear narrative films

- French films

- War romance films

- Focus Features films

- Relativity Media films

- StudioCanal films

- Universal Pictures films

- Working Title Films films

- British World War II films

- French World War II films

- German World War II films