Attleboro, Massachusetts

Attleboro, Massachusetts | |

|---|---|

City | |

Attleboro's city hall | |

Seal | |

| Nicknames: The Jewelry City, A-Town | |

| Motto(s): Go Big Blue | |

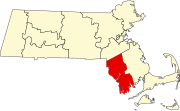

Location in Bristol County in Massachusetts | |

Attleboro Location in Massachusetts | |

| Coordinates: 41°55′54″N 71°17′40″W / 41.931653°N 71.294503°WCoordinates: 41°55′54″N 71°17′40″W / 41.931653°N 71.294503°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Bristol |

| Settled | 1634 |

| Incorporated | 1694 (town) |

| Reincorporated | 1914 (city) |

| Named for | Attleborough, England |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-council city |

| • Mayor | Paul Heroux (D) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 27.772 sq mi (71.930 km2) |

| • Land | 26.779 sq mi (69.356 km2) |

| • Water | 0.994 sq mi (2.574 km2) |

| Elevation | 138 ft (42 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 43,593 |

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 45,237 |

| • Density | 1,600/sq mi (610/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5:00 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4:00 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 02703 |

| Area code(s) | 508 / 774 |

| FIPS code | 25-02690 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0612033 |

| Website | www |

Attleboro is a city in Bristol County, Massachusetts, United States. It was once known as "The Jewelry Capital of the World" for its many jewelry manufacturers. According to the 2010 census, Attleboro had a population of 43,593 in 2010.[4]

Attleboro is located about 10 miles (16 km) west of Taunton, 10 miles north of Providence, 18 miles (29 km) northwest of Fall River, and 39 miles (63 km) south of Boston.

History[]

In 1634, English settlers first arrived in the territory that is now Attleboro.[5] The deed that granted them the land was written by Native American Wamsutta. The land was divided in 1694 as the town of Attleborough.[6] It included the towns of Cumberland, Rhode Island, until 1747 and North Attleborough, Massachusetts, until 1887. In 1697 in response to an unwanted amount of disturbances, mainly from nearby tribes of natives, the town had a meeting and ended up deciding that selectmen would keep tabs on strangers and foreigners as well as banning certain ones from entering the town. The town was reincorporated in 1914 as the City of Attleboro, with the "-ugh" removed from the name, although North Attleborough kept it. Like many towns in Massachusetts, it was named for a British town.

During the Native American insurgency in the colonial era, Nathaniel Woodcock, the son of an Attleborough resident, was murdered, and his head was placed on a pole in his father's front yard. His father's house is now a historical site. It is rumored that George Washington once passed through Attleborough and stayed near the Woodcock Garrison House at the Hatch Tavern, where he exchanged a shoe buckle with Israel Hatch, a revolutionary soldier and the new owner of the Garrison House.

The city became known for jewelry manufacturing in 1913, particularly because of the L.G. Balfour Company. That company has since moved out of the city, and the site of the former plant has been converted into a riverfront park. Attleboro was once known as "The Jewelry Capital of the World", and jewelry manufacturing firms continue to operate there. One such is the Guyot Brothers Company, which was started in 1904.[7] General Findings, M.S. Company, James A. Murphy Co., Garlan Chain, Leach & Garner, and Masters of Design are jewelry manufacturing companies still in operation.

Cancer cluster[]

In late 2003, The Sun Chronicle reported that a state investigation had been launched into the deaths of four women in the city from glioblastoma.[citation needed] In 2007, the State of Massachusetts issued a report concluding that although the diagnosis rate for brain and central nervous system (CNS) cancers was higher than expected when compared to statewide data, the increase was determined not to be statistically significant.[8]

Scorecard, Environmental Defense's online database of polluters, lists seven facilities contributing to cancer hazards in Attleboro, including Engineered Materials Solutions Inc., the worst offender in Massachusetts.[9]

Shpack Landfill contamination incident[]

In 2002, the Massachusetts Public Health Department was asked to evaluate the former Shpack Landfill, on the border of Norton and Attleboro, for its cancer risks. The investigation continued at least through 2004.[10][11] The informal landfill included uranium fuel rods, heavy metals, and volatile organic compounds.[12]

Geography[]

Attleboro is located at 41°55′54″N 71°17′40″W / 41.931653°N 71.294503°W and has a total area of 27.772 square miles (71.930 km2), of which 26.779 square miles (69.356 km2) is land and 0.994 square miles (2.574 km2), or 3.59%, is water.[13] Its borders form an irregular polygon that resembles a truncated triangle pointing west. It is bordered by North Attleborough to the north, Mansfield and Norton to the east, Rehoboth, Seekonk, and Pawtucket, Rhode Island, to the south, and Cumberland, Rhode Island, to the west, as well as sharing a short border with Central Falls, Rhode Island through the Blackstone River. It includes the areas known as City Center, Briggs Corner, West Attleboro, East Corner, East Attleboro, North Corner, Maple Square, Camp Hebron, Oak Hill, Dodgeville, East Junction, Hebronville, Park Square, and South Attleboro.

The Ten Mile River, fed by the Bungay River and by several brooks, runs through the center of Attleboro. The Manchester Pond Reservoir lies beside Interstate 95, and there are several small ponds in the city. There are over twenty conservation areas amounting to more than 600 acres of walkable woods</ref>:the Antony Lawrence Preserve, Coleman Reservation, Attleboro Springs as well as the Bungay River Conservation Area in the north of the city. The highest point in Attleboro is 249-foot (76 m) Oak Hill, located in the southern part of the city north of Oak Hill Avenue.[14]

Attleboro sits on the border between the Massachusetts and Rhode Island regional dialects of New England English: the eastern part of the city is in the same dialect region as Boston, and the western part is in the same dialect region as Providence.[15]

Demographics[]

Attleboro is part of the Providence metropolitan area. It is a short distance from Boston, and is linked to the Boston metropolitan area.

As of the 2010 census, there were 43,593 people, 16,884 households, and 11,212 families living in the city; the population density was 1,626.6 inhabitants per square mile (628.0/km2). There were 18,022 housing units at an average density of 672.5 per square mile (259.7/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 87.1% White, 3.0% African American, 0.2% Native American, 4.5% Asian (1.5% Cambodian,1.3% Indian, 0.4% Chinese, 0.4% Vietnamese) 0.1% Pacific Islander, 2.8% some other race, and 2.2% from two or more races. Hispanic and Latino people of any race made up 6.3% of the total (2.0% Puerto Rican, 1.7% Guatemalan, 0.5% Mexican, 0.4% Salvadoran, 0.3% Dominican, 0.2% Colombian).[28] Most of the Hispanic and Asian populations were concentrated in the East Side.[citation needed]

Of the 16,884 households, 33.3% had someone under the age of 18 living with them, 50.1% were headed by married couples living together, 11.3% had a female householder with no husband present, 33.6% were non-families, 26.4% were individuals, and 9.8% were people aged 65 or older living alone. The average size of household was 2.55 and the average family size was 3.11.[28]

The age distribution in the city was: 22.7% under 18, 7.9% from 18 to 24, 28.5% from 25 to 44, 28.0% from 45 to 64, and 12.9% over 64. The median age was 39.5 years. For every 100 females, there were 95.5 males. For every 100 females aged 18 and over, there were 93.3 males.[28]

For the period 2009–2011, the estimated median annual income for a household in the city was $63,647, and the median income for a family was $71,091. Male full-time workers had a median income of $52,558, females $40,954. Per capita income was $30,039. About 4.2% of families and 6.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 6.4% of those under 18 and 7.8% of those aged 65 or over.[29]

Economy[]

Revitalization efforts[]

In December 2011, the City of Attleboro was awarded US$5.4 million in state and federal funding to support revitalization efforts within the city's Historic Downtown area.[30] The city's "Downtown Redevelopment and Revitalization Project"[30] is intended to transform underutilized industrial and commercial parcels into areas of mixed use that include commercial, recreational, and residential space. The project also includes transportation improvements to both MBTA rail and GATRA bus services along with enhanced road construction.[30]

The city project was also selected for the state Brownfield Support Team (BST) Initiative,[30] which encourages collaboration between state, local, and federal government to address complex issues to help pave the way for economic development opportunities in cities and towns across the state of Massachusetts. Contributing BST organizations include the MassDEP, Mass Development, the Department of Housing and Community Development (DHCD), and the MassDOT.[30]

Congressman Jim McGovern highlighted the importance of this project in 2011 by saying,

This transformative funding presents a landmark opportunity for Attleboro to reshape its downtown and make a strong community even stronger. The new transit plan, when implemented, will make Attleboro a model for other small cities, and the aggressive reclaiming of contaminated sites will enhance economic development.

Government[]

Attleboro is represented in the state legislature by officials elected from the following districts:

- Massachusetts Senate's Bristol and Norfolk district[31]

- Massachusetts Senate's Norfolk, Bristol and Middlesex district

- Massachusetts House of Representatives' 2nd Bristol district[32]

- Massachusetts House of Representatives' 14th Bristol district

Attractions[]

Attleboro has four museums.

- The Attleboro Arts Museum

- The Attleboro Area Industrial Museum,[33]

- The Women at Work Museum

- The Museum at the Mill.

Other places of interest in the city include:

- Capron Park Zoo;[34]

- L.G. Balfour Riverwalk, which was once the site of the L.G. Balfour jewelry plant, adjacent to the downtown business district

- La Salette Shrine, which has a display of Christmas lights[35]

- Oak Knoll Wildlife Sanctuary, 75 acres owned by the Massachusetts Audubon Society with a visitor center

- Triboro Youth Theatre / Triboro Musical Theatre;[36]

- Attleboro Community Theatre;[37] *Dodgeville Mill.

- Skyroc Brewery [38]

- Attleboro Farmers Market [39]

In 2017, Attleboro began hosting the annual Jewelry City Steampunk Festival.

Infrastructure[]

Attleboro High School[]

The high school is getting an entirely new building. The building that is currently being used was built in the 1960s on Rathbun Willard Drive and is not in the best shape of its life currently. The city of Attleboro had a vote on whether or not to build a brand new school or renovate the current building, "Heroux said he and school officials reached an agreement to put proceeds from the sale toward the cost of a new high school before the $260 million was approved by voters last spring."[40]. The only reason they had a vote was that they were selling the first Attleboro High School that was built in 1912 on County Street, which would give the city a good amount of the money they need for the new building. There is a virtual tour of the new building to show others what it will look like and what to expect from the interior. As well as the entire plan for the building. Currently there is a new high school being built right next to the current school. The new Attleboro high school is slated to open in 2022. [41][42]

Transportation[]

Attleboro is located beside Interstate 95 (which enters the state between Attleboro and Pawtucket, Rhode Island), I-295 (whose northern terminus is near the North Attleborough town line at I-95), US Route 1, and Routes 1A, 118, 123 and 152, the last three of which intersect at Attleboro center. The proposed Interstate 895 was to run through Attleboro and have a junction at the present day I-295/I-95 terminus. When driving from Rhode Island on I-295, the stub exits before the half-cloverleaf exit to I-95.

The city is home to two MBTA commuter rail stations: one in the downtown area and the other in the South Attleboro district, near the Rhode Island border. Attleboro and Taunton are both served by the Greater Attleboro Taunton Regional Transit Authority, or GATRA, which provides bus transit between the two cities and the surrounding regions.

Education[]

Attleboro's school department has five elementary schools (Hill-Roberts, Hyman Fine, A. Irvin Studley, Peter Thacher and Thomas Willett), three middle schools (Brennan, Coelho and Wamsutta), and two high schools (Attleboro High School, and Attleboro Community Academy). Attleboro High School has its own vocational division, and its football team (the "Blue Bombardiers") has a traditional rivalry with North Attleborough High School, whom they play for their Thanksgiving Day football game. Attleboro Community Academy is a night school for students aged 16–25 to obtain their highschool diplomas and could not function in traditional high school. Bishop Feehan High School is a co-educational Roman Catholic high school which opened in 1961 and is named for Bishop Daniel Francis Feehan, second Bishop of the Diocese of Fall River. The city also has a satellite branch of Bristol Community College, which used to be housed in the city's former high school building but has since been relocated to an old Texas Instruments site. Bridgewater State University opened a satellite site in Attleboro in 2009, sharing space with Bristol Community College.

Religion[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2012) |

Religion reflects the historic ethnic makeup of the community. The Attleboro Area Interfaith Collaborative[43] was founded in 1946 to serve the community.

There are three parishes[44] in the Roman Catholic Diocese of Fall River:

- St. John the Evangelist Parish reflecting the English and Irish neighborhoods

- St. Theresa of the Child Jesus Parish[45] reflecting the former French (now Hispanic) neighborhoods

- St. Vincent de Paul Parish reflecting the Portuguese neighborhoods

There are two Orthodox churches:

- Holy Family Coptic Orthodox Church (Oriental Orthodoxy)

- Holy Annunciation Church, Greek Orthodox Christian (Eastern Orthodoxy)

There are various Protestant churches:

- Three in the Anglican Communion:

- All Saints Episcopal Church[46] was founded in 1890. It provides a traditional Anglican presence.

- All Saints Anglican Church[47] in the Hebronville village split from the Episcopal church in town in 2007 over liberal policies of the denomination. This church is affiliated with an Anglican diocese in Uganda.

- St. James Community Church (Kenyan)

- Three Baptist churches:

- Two Lutheran churches:

- Good Shepherd Lutheran Church

- Immanuel Lutheran Church[51]

- Second Congregational Church,[52] United Church of Christ, founded near the town common in 1748, is typical of a New England town and is the founding church of what was then East Attleboro. It is a daughter church of the First Congregational (now Oldtown) Church of North Attleborough. Originally located in a meeting house on what is now the common, it had a stately white clapboard building built in 1825. It was removed in the early 1950s to make way for the addition of a new Fellowship Hall and education rooms. The main red brick building and clock tower were built in 1904 beside the white church. In the early 1960s the interior of the sanctuary and the entrance were dramatically remodeled, resulting in a blend of high Victorian style and the open feel of mid-century modern. The church owns the Old Kirk Yard Cemetery to its rear, where many of the town's earliest families are buried. In its tower is the clock, owned originally by the city and now by the church. The Jack & Jill School has operated at the church for over 70 years. One of the city's elementary schools is named in honor of the church's first settled minister, the Reverend Peter Thacher.

- Centenary United Methodist Church[53] on North Main Street began on November 26, 1865 as a fellowship meeting in a building on Railroad Avenue. The first church building on the present site was dedicated in 1896 under the name of Davis Methodist Episcopal Church. The structure was destroyed by fire in 1883. The rebuilt church was named Centenary Methodist Episcopal Church in 1884, commemorating American Methodism's 100th anniversary. In 1998 Centenary and the Hebron Methodist were consolidated into one church.

- Bethany Village Fellowship[54] formed in 1886 as Bethany Congregational Church.

- Evangelical Covenant Church[55] founded in 1903 as the Swedish Evangelical Church on Pearl Street. The building was sold to Congregation Agudas Achim in 1911.[56]

- Good News Bible Chapel[57] (1935), non-denominational

- New Covenant Christian Fellowship,[58] non-denominational (2006)

- Advent Christian Church,[59] National Association of Evangelicals

- Attleboro Corps Community Center,[60] The Salvation Army offers weekday and evening support services, including "Bridging the Gap" for adolescents.

- Candleberry Chapel,[61] non-denominational

- Crossroads International Church,[62] Assembly of God in South Attleboro

- Faith Alliance Church[63] is a part of the Christian & Missionary Alliance

- Fruit of the Spirit Mission Church, non-denominational

- Seventh-day Adventist Church[64] is located across from Capron Park

- Spanish Seventh-day Adventist Church

- United Pentecostal Church

Ark Celeste Christian Church

New Heart and New Spirit Church

Spanish Church of God

Iglesia La Familia De Dios

First Church of Christ, Scientist

Kingdom Hall of Jehovah's Witnesses

Congregation Agudas Achim is part of the Reconstructionist Judaism movement. The congregation formally started in 1911 with the purchase of the Swedish Evangelical Church on Pearl Street. The current synagogue was built in 1968.

Murray Unitarian-Universalist Church (1875)[65]

The National Shrine of Our Lady of La Salette[]

In 1942, the Missionaries of La Salette purchased 135 acres (0.55 km2) and a castle in Attleboro for use as a seminary.[66] The shrine was opened to the public in 1953 with a Christmas manger display.[67][66] The annual Christmas Festival of Lights has grown to an annual display of 300,000 lights and attracts about a quarter million visitors each year.[66] A devastating fire destroyed the castle on November 5, 1999.[66] A new welcome center was opened in 2007 which includes a 600-seat concert hall.[66] In addition to the Christmas Festival, the shrine offers programs, concerts, workshops and events throughout the year.[67][66] The grounds also include Our Lady's Chapel of Lights, an outdoor chapel, and a church.[66]

Notable people[]

- Artine Artinian (1907-2005), scholar of French literature

- Cathy Berberian (1925–1983), composer, mezzo-soprano singer, and vocalist born in Attleboro

- Roger Bowen (1932–1996), comedic actor known for his portrayal of Lt. Col. Henry Blake in the 1970 film MASH; co-founder of comedy troupe The Second City

- George Bradburn (1806–1880), an American politician and Unitarian minister in Massachusetts, known for his support for abolitionism and women's rights[68]

- Geoff Cameron (born 1985), professional soccer player

- Horace Capron (1804–1885), Union Army officer during the Civil War and later an agricultural advisor to Japan; his methods revolutionized Japanese agriculture[69]

- David Cobb (1748–1830), major general of the Continental Army, speaker of the Massachusetts House of Representatives, United States Congressman from Massachusetts[69]

- Ray Conniff (1916–2002), Easy listening recording artist

- Mark Coogan (born 1966) is a coach and retired American track athlete. Coogan was the first Massachusetts native to run the mile in under four minutes.[1] He ran the marathon at the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta, placing 41st with a time of 2:20:27, after placing second in the U.S. Olympic Trials Marathon with at time of 2:13:05.

- David Daggett (1764–1851), United States Senator, associate justice of Connecticut Supreme Court, mayor of New Haven, Connecticut, and a founder of the Yale Law School[69]

- Naphtali Daggett (1727–1780), Presbyterian clergyman, professor of divinity at Yale University, fought in the American Revolutionary War[69]

- Paul G. Gaffney II, President, Monmouth University, US Navy Vice Admiral (Ret.), former Chief of Naval Research, President of National Defense University;

- William Manchester (1922–2004), historian and biographer, author of The Death of a President

- Jonathan Maxcy (1768–1820), Baptist clergyman and president of Brown University[69]

- Virgil Maxcy (1785–1844), member of the Maryland House of Delegates and the Maryland State Senate, later first solicitor of the treasury and chargé d'affaires at the United States embassy in Belgium[69]

- Christian Petersen (1885-1961), sculptor who worked as a die-cutter in Attleboro

- Helen Watson Phelps (1864–1944), painter

- Daniel Read (1757–1836), composer, who published 400 hymns in several collections[70]

- Robert Rounseville (1914–1974), operatic tenor, who appeared in the films The Tales of Hoffmann and Carousel, and onstage in the original productions of the musicals Candide and Man of La Mancha

- Ken Ryan (1968– ), former pitcher for the Boston Red Sox and Philadelphia Phillies

- Thomas Hobson, American actor, singer

- Howard Smith (1893–1968), American actor, singer

- Robert A. Weygand (1948– ), member of the US House of Representatives 1997–2001[71]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Hand, Jim (30 December 2017). "TOP 10 STORIES OF 2017: Heroux's victory was number one local story". The Sun Chronicle. Attleboro. Archived from the original on 31 December 2017. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ^ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (DP-1): Attleboro city, Massachusetts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 2, 2011.

- ^ "Attleboro Timeline". City of Attleboro Historical Commission. Archived from the original on 2011-08-11. Retrieved 2012-05-30.

- ^ "Sketch of the History of Attleborough: From Its Settlement to the Present Time". Mocavo. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ "Brief history of jewelry findings manufacturer Guyot Brothers". Guyot Brothers Company, Inc. 2003–2007. Archived from the original on 15 June 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-09.

- ^ "Evaluation of Brain & CNS Cancer Incidents in Attleboro, MA 1999–Present" (PDF). Commonwealth of Massachusetts. 2007.

- ^ "Facilities Contributing to Cancer Hazards in Massachusetts". Scorecard. 2005. Retrieved 2007-06-09.

- ^ "Cancer Clusters". WBZ News (I-Team). March 2, 2004. Retrieved 2007-06-09.[dead link]

- ^ Massey, Joanna (January 25, 2004). "Norton leaders upset at US delay on cleanup". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on March 13, 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-09.

- ^ "Waste Site Cleanup & Reuse in New England — Shpack Landfill". US Environmental Protection Agency. February 15, 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-09.

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Attleboro city, Massachusetts". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Attleboro, MA 7.5 by 15-minute quadrangle, 1987.

- ^ Johnson, Daniel Ezra (2010), Stability and change along a dialect boundary: the low vowels of Southeastern New England, Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press

- ^ "Total Population (P1), 2010 Census Summary File 1". American FactFinder, All County Subdivisions within Massachusetts. United States Census Bureau. 2010.

- ^ "Massachusetts by Place and County Subdivision - GCT-T1. Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1990 Census of Population, General Population Characteristics: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1990. Table 76: General Characteristics of Persons, Households, and Families: 1990. 1990 CP-1-23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1980 Census of the Population, Number of Inhabitants: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1981. Table 4. Populations of County Subdivisions: 1960 to 1980. PC80-1-A23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1950 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. 1952. Section 6, Pages 21-10 and 21-11, Massachusetts Table 6. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1930 to 1950. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1920 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. Number of Inhabitants, by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions. Pages 21-5 through 21-7. Massachusetts Table 2. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1920, 1910, and 1920. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1890 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. Pages 179 through 182. Massachusetts Table 5. Population of States and Territories by Minor Civil Divisions: 1880 and 1890. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1870 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1872. Pages 217 through 220. Table IX. Population of Minor Civil Divisions, &c. Massachusetts. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1860 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1864. Pages 220 through 226. State of Massachusetts Table No. 3. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1850 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1854. Pages 338 through 393. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1950 Census of Population" (PDF). 1: Number of Inhabitants. Bureau of the Census. 1952. Section 6, Pages 21–07 through 21-09, Massachusetts Table 4. Population of Urban Places of 10,000 or more from Earliest Census to 1920. Retrieved July 12, 2011. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (DP-1): Attleboro city, Massachusetts". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ^ "Selected Economic Characteristics: 2009–2011 American Community Survey 3-Year Estimates (DP03): Attleboro city, Massachusetts". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Official Website of the Governor of Massachusetts. (2011). Lieutenant Governor Murray Announces $5.4 Million to Support Attleboro's Downtown Redevelopment and Revitalization Project [Press Release] Retrieved from http://www.mass.gov/governor/pressoffice/pressreleases/2011/111216-attleboro-redevelopment-plan.html

- ^ Massachusetts General Court, "An Act Establishing Executive Councillor and Senatorial Districts", Session Laws: Acts (2011), retrieved August 23, 2020

- ^ "Massachusetts Representative Districts". Sec.state.ma.us. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- ^ "About Attleboro Area Industrial Museum". Attleboro Area Industrial Museum, Inc. 2007. Archived from the original on 2003-02-08. Retrieved 2007-06-09.

- ^ "About the Capron Park Zoo". Capron Park Zoo. 2007. Archived from the original on 7 June 2007. Retrieved 9 June 2007.

- ^ "The History of the National Shrine of Our Lady of La Salette". National Shrine of Our Lady of La Salette. 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-02-23. Retrieved 2007-06-09.

- ^ "Triboro Youth Theatre". 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-02-22. Retrieved 2007-06-09.

- ^ "Attleboro Community Theatre, Inc". Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ "Skyroc Brewery". Skyroc Brewery. Retrieved 2021-05-06.

- ^ "Attleboro Farmers Market". 2021-03-15. Retrieved 2021-05-07.

- ^ jhand@thesunchronicle.com, Jim Hand. "School committee hands old Attleboro High School back to the city". The Sun Chronicle. Retrieved 2021-05-06.

- ^ "Attleboro High School Project | Attleboro, MA". www.cityofattleboro.us. Retrieved 2021-05-07.

- ^ "Home". ahs.attleboroschools.com. Retrieved 2021-05-07.

- ^ "About Us – Attleboro Area Interfaith Collaborative".

- ^ https://attleborocatholics.org/

- ^ https://www.sainttheresaattleboro.org/

- ^ https://allsaints-episcopal.org/

- ^ http://allsaintsattleboro.org/about/about

- ^ "First Baptist Church, Attleboro".

- ^ "About".

- ^ "Home". Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ https://immanuellc.org/who-we-are/

- ^ http://www.attleborosecondchurch.org/

- ^ "Centenary United Methodist Church – Come and See – Go and Tell – Attleboro, MA". Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ http://bethanyvillagefellowship.com/

- ^ https://www.eccattleboro.org/who-we-are

- ^ https://www.agudasachimma.org/history.htm

- ^ "Good News Bible Chapel". Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ New Covenant Christian Fellowship Archived 2010-07-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ https://aacchurch.com/hp_wordpress/welcome-4/who-we-are/

- ^ https://massachusetts.salvationarmy.org/MA/Attleboro

- ^ http://www.candleberrychapel.com/contact-us.html

- ^ https://cic.church/

- ^ "Faith Alliance Church of Attleboro, MA". Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ https://attleboroma.adventistchurch.org/about}

- ^ "Murray Unitarian Universalist Church". Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "15 years after devastating fire, LaSalette Shrine's mission greater than ever". The Sun Chronicle. 24 November 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Our History". National Shrine of Our Lady of La Salette. Attleboro, Massachusetts. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ A Memorial of George Bradburn, Frances H. Bradburn, 1883

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Who Was Who in America, Historical Volume, 1607–1896. Chicago: Marquis Who's Who. 1963.

- ^ "Daniel Read". The History Channel. Archived from the original on 2007-08-11. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

- ^ "Weygand, Robert A". The United States Congress. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Attleboro, Massachusetts. |

- Attleboro, Massachusetts

- 1634 establishments in Massachusetts

- Cities in Bristol County, Massachusetts

- Cities in Massachusetts

- Populated places established in 1634

- Providence metropolitan area