Haverhill, Massachusetts

This article has an unclear citation style. (May 2010) |

Haverhill, Massachusetts | |

|---|---|

City | |

| City of Haverhill | |

Haverhill from across the Merrimack River | |

Flag  Seal | |

| Nickname(s): "The Queen Slipper City" | |

Location in Essex County, state of Massachusetts, New England. | |

Haverhill, Massachusetts Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 42°47′N 71°5′W / 42.783°N 71.083°WCoordinates: 42°47′N 71°5′W / 42.783°N 71.083°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Massachusetts |

| County | Essex |

| Settled | 1640 |

| Incorporated | 1641 |

| Incorporated (city) | 1870 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-council city (Strong Mayor) |

| • Mayor | James J. Fiorentini |

| Area | |

| • Total | 35.70 sq mi (92.45 km2) |

| • Land | 33.04 sq mi (85.56 km2) |

| • Water | 2.66 sq mi (6.89 km2) |

| Elevation | 50 ft (20 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 60,879 |

| • Estimate (2019)[1] | 64,014 |

| • Density | 1,937.70/sq mi (748.14/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (Eastern) |

| ZIP Codes | 01830–01832, 01835 |

| Area code(s) | 351/978 |

| FIPS code | 25-29405 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0612607 |

| Website | www |

Haverhill (/ˈheɪvrɪl/ HAY-vril) is a city in Essex County, Massachusetts, United States. Haverhill is located 35 miles north of Boston on the New Hampshire border and about 17 miles from the Atlantic Ocean. The population was 60,879 at the 2010 census.[3]

Located on the Merrimack River, Haverhill began as a farming community of Puritans, largely from Newbury Plantation. The land was officially purchased from the Pentuckets on November 15, 1642 (One year after incorporation) for three pounds, and ten shillings.[4][5] Pentucket was renamed Haverhill (after the Ward family's hometown in England) and evolved into an important industrial center, beginning with sawmills and gristmills run by water power. In the 18th and 19th century, Haverhill developed woolen mills, tanneries, shipping and shipbuilding. The town was home to a significant shoe-making industry for many decades. By the end of 1913, one tenth of the shoes produced in the United States were made in Haverhill, and because of this the town was known during the time as the "Queen Slipper City".

History[]

Haverhill has played a role in nearly every era of American history, from the initial colonial settlement, to the French and Indian Wars, and the American Revolutionary and Civil wars.[6]

17th century[]

The town was founded in 1640 by settlers from Newbury, and was originally known as Pentuckett, which is the Native American word for "place of the winding river". Settlers such as John Ward, Robert Clements, Tristram Coffin, Hugh Sheratt, William White, and Thomas Davis aided in the purchase of Pentuckett. The land was sold by native Indian chiefs Passaquo and Saggahew and permission was granted by Passaconaway, chief of the Pennacooks. Settlers Thomas Hale, Henry Palmer, Thomas Davis, James Davis and William White were its first selectmen. First Court appointments; given to end small causes were given to Robert Clements, Henry Palmer, and Thomas Hale. At the same court, it was John Osgood and Thomas Hale that were also appointed to lay the way from Haverhill to Andover.[7] It is said that these early settlers worshipped under a large oak tree, known as the "Worshipping Oak".[8]

The town was renamed for the town of Haverhill, England,[9] in deference to the birthplace of the settlement's first pastor, Rev. John Ward.[10] The original Haverhill settlement was located around the corner of Water Street and Mill Street, near the Linwood Cemetery and Burying Ground. The home of the city's father, William White, still stands, although it was expanded and renovated in the 17th and 18th centuries. White's Corner (Merrimack Street and Main Street) was named for his family, as was the at Boston's Museum of Fine Arts.

Judge Nathaniel Saltonstall was chosen to preside over the Salem witch trials in the 17th century; however, he found the trials objectionable and recused himself. Historians cite his reluctance to participate in the trials as one of the reasons that the witch hysteria did not take as deep a root in Haverhill as it did in the neighboring town of Andover, which had among the most victims of the trials. However, a number of women from Haverhill were accused of witchcraft, and a few were found "guilty" by the Court of Oyer and Terminer.

One of the initial group of settlers, Tristram Coffin, ran an inn. However, he grew disenchanted with the town's stance against his strong ales, and in 1659 left Haverhill to become one of the founders of the settlement at Nantucket.

Haverhill was for many years a frontier town, and was occasionally subjected to Indian raids, which were sometimes accompanied by French colonial troops from New France, in which dozens of civilians were murdered. During King William's War, Hannah Dustin became famous for killing and then scalping her native captors, who were converts to Catholicism, after being captured in the Raid on Haverhill (1697). The city has the distinction of featuring the first statue erected in honor of a woman in the United States. In the late 19th century, it was Woolen Mill Tycoon Ezekiel J. M. Hale that commissioned a statue in her memory in Grand Army Republic Park. The statue depicts Dustin brandishing an axe and several Abenaki scalps.[11] Her captivity narrative and subsequent escape and revenge upon her captors caught the attention of Cotton Mather, who wrote about her, and she also demanded from the colonial leaders the reward per Indian scalp. In recent years some have criticized Hannah Dustin since the Native American Indians she killed and scalped in order to escape were allegedly not her original captors and among the people she killed were young children. Hannah, born Hannah Emerson, is often maligned for coming from a troubled family: in 1676 her father Michael Emerson was fined for excessive violence toward his 12-year-old daughter Elizabeth, who in 1693 was hanged for concealing the deaths of her illegitimate twin daughters; and in 1683 Hannah's sister Mary was whipped for fornication. There were never any allegations of any sort against Hannah herself.[12]

18th century[]

In 1708, during Queen Anne's War, the town, then about thirty homes, was raided by a party of French, Algonquin and Abenaki Indians.Like most towns, Haverhill has been struck by several epidemics. Diphtheria killed 256 children in Haverhill between November 17, 1735 and December 31, 1737.[13]

George Washington visited Haverhill on November 4, 1789. Washington was on a "triumphant circuit" touring New England.

19th century[]

The Bradford Academy was established in 1803. It began as a co-educational institution, then became women-only in 1836.[14]

In 1826, an influenza struck. A temperance society was formed in 1828.

Haverhill residents were early advocates for the abolition of slavery, and the city still retains a number of houses which served as stops on the Underground Railroad. In 1834, a branch of the American Anti-Slavery Society was organized in the city. In 1841, citizens from Haverhill petitioned Congress for dissolution of the Union, on the grounds that Northern resources were being used to maintain slavery. John Quincy Adams presented the Haverhill Petition on January 24, 1842.[10] Even though Adams moved that the petition be answered in the negative, an attempt was made to censure him for even presenting the petition.[15] In addition, poet and outspoken abolitionist John Greenleaf Whittier was from Haverhill.

The Haverhill and Boston Stage Coach company operated from 1818 to 1837 when the railroad was extended to Haverhill from Andover. It then changed its name and routes to the Northern and Eastern Stage company.

It was Ezekiel Hale Jr. and son Ezekiel James Madison Hale (descendants of Thomas Hale) that gave Haverhill a great head of steam. It was in the summer of 1835, the brick factory on Winter St was erected by Ezekiel Hale Jr. and Son. It was intended to run woolen flannel at a whopping six hundred yards of flannel per day. It was Ezekiel JM Hale, age 21 and graduate of Dartmouth College that came to the rescue when fire destroyed the operation in 1845. He rebuilt the mill at Hale's Falls, now more than twice as large produced nearly three times the output. Ezekiel JM Hale became Haverhill's Tycoon. EJM Hale served a term in the State Senate and was much revered in the area. Hale donated large sums of money to build the hospital and library.[16]

Haverhill was incorporated as a city in 1870.

In the early morning hours of February 17, 1882, a massive fire destroyed much of the city's mill section, in a blaze that encompassed over 10 acres (4.0 ha). Firefighting efforts were hampered by not only the primitive fire fighting equipment of the period, but also high winds and freezing temperatures. The nearby water source – the Merrimack River – was frozen, and hoses dropped through the ice tended to freeze as well. A New York Times report the next day established the damage at 300 businesses destroyed and damage worth approximately $2M (in 1882 dollars).[17][18][19]

Annexation[]

Bradford fits naturally into Haverhill but they were separate towns until January 1, 1897, when Bradford joined the City of Haverhill. Bradford was originally the western part of Rowley until it split from Old Rowley in 1672. In 1850, the East part of Bradford left and was founded as the independent town of Groveland. When Haverhill became a city in 1870, there were calls for the town to be annexed. This would go on for another 26 years. Neither town agreed to a plan, until in late 1896, the vote came up and both sides agree to join.

There were many reasons for the decision. Finances played a part into the annexation; a lot of people who lived in Bradford had businesses in Haverhill and wanted lower taxes. Traditionalists wanted Haverhill to be a dry town as Bradford was. Businesses in Lawrence, Portsmouth, and Andover wanted Haverhill to be a dry town so more business would show up and increase businesses in those towns. The demand for municipal services like hospitals, schools, and a new factory downtown were in Haverhill while Bradford had none of the three. The Bradford Center of town wanted to join Haverhill but the Ward Hill section of town did not at the time since it was a substantial distance from both Bradford and Haverhill.

Finally, another reason why Haverhill wanted to annex Bradford was to return the town to majority English instead of the plurality of Irish, French Canadians and Central Europeans (Hungarians, Slovaks, Germans, and Italians) it had become with the influx of mill workers. Haverhill gladly approved with the first ballot in 1870 and Bradford was no more starting January 1, 1897. Bradford remains the only town in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts to be annexed to a neighboring city other than Boston.

Haverhill became the first American city with a socialist mayor in 1898 when it elected former shoe factory worker and cooperative grocery store clerk John C. Chase.[20] Chase was re-elected to this position in 1899 but was defeated the following year.

20th century[]

Haverhill was the site of a riot in 1915 as well as the eponymous Haverhill fever, also known as rat-bite fever, in 1926.

In the early part of the 20th century, the manufacturing base in the city came under pressure as a result of lower priced imports from abroad. The Great Depression exacerbated the economic slump, and as a result city leaders enthusiastically embraced the concept of urban renewal in the 1950s and 1960s, receiving considerable federal funds used to demolish much of the north side of Merrimack Street, most of the Federal homes along Water Street (dating from the city's first hundred years of development), and throughout downtown. Many of the city's iconic buildings were lost, including the Oddfellows Hall, the Old City Hall, the Second Meetinghouse, the Pentucket Club, and the Old Library, among others.

During Urban Renewal, the iconic high school—the inspiration for Bob Montana's Archie Comics[21]—was declared "unsound" and slated for demolition. Instead, the historic City Hall on Main Street was demolished, and city began using the High School of Archie's Gang as the new City Hall.

Urban Renewal was controversial. Several leading citizens argued to use the funds for preservation rather than demolition. Their plan was not accepted in Haverhill, which chose to demolish much of its historic downtown, including entire swaths of Merrimack Street, River Street, and Main Street. However, examples of the city's architecture, spanning nearly four centuries, abound: from early colonial houses (the White residence, the Duston Garrison House, the 1704 John Ward House, the 1691 Kimball Tavern, and the historic district of Rocks Village) to the modernist 1960s architecture of the downtown Haverhill Bank. The city's Highlands district, adjacent to downtown, is a fine example of the variety of Victorian mansions built during Haverhill's boom years as a shoe manufacturing city.[citation needed]

21st century[]

In the 21st century, downtown Haverhill has undergone a renaissance of sorts. Housing trends, combined with a rezoning by the city led by longtime Mayor James Fiorentini and the use of Federal and State brownfield's money to clean up abandoned factories, resulted in the conversion of several abandoned factories into loft apartments and condominiums. There has been a total of $150 million in public and private investment in the downtown old factory district area. Additionally, the Washington Street area gained new dining and entertainment spots, and federal, State and local funds contributed to removing an abandoned gas station on Granite Street, cleaning up the site and converting it to a 350-space parking garage. The city was able to obtain Federal, State and local money to put in a new boardwalk and boat docks downtown.[22] Recently, the city completed a rezoning of downtown proposed by Mayor Fiorentini designed to encourage artist loft live work space and educational uses for the downtown area. Despite the city's efforts, old buildings remain vacant or underutilized, such as the former Woolworth department store – boarded up for 40+ years at the intersection of Main Street and Merrimack Street. Recently a group purchased that building with the intention of redeveloping it, however those plans fell through. In February 2014, it was announced that plans were made to redevelop "Whites Corner" by demolishing the vacant Woolworth building along with other surrounding buildings including the former Newman's Furniture, Ocasio Building, replacing them with the new mixed-use project called Harbor Place. Those buildings along with other smaller ones were officially demolished as of March 19, 2015 making way for the construction of the Harbor Place project. As of July 23, 2016 the construction on the Harbor Place buildings are well underway as the mixed use building is near completion and the housing building is making progress. In September 2016, the Haverhill Riverfront Boardwalk overlooking the Merrimack River has opened to the public that extends from the Harbor Place buildings connecting to the other boardwalk behind Haverhill Bank.

Timeline[]

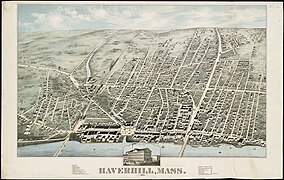

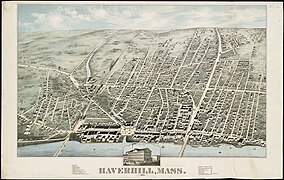

View of Haverhill, 1850

Map of Haverhill, 1876

City Hall, built 1889

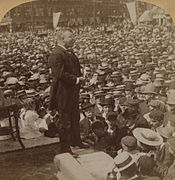

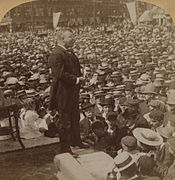

Teddy Roosevelt addressing crowd in Haverhill, 1902

Aerial view of Haverhill, 2008

Geography[]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 35.6 square miles (92.3 km2), of which 33.0 square miles (85.4 km2) is land and 2.7 square miles (6.9 km2), or 7.47%, is water.[40] The city ranks 60th in the Commonwealth in terms of land area, and is the largest city or town in Essex County. Haverhill is drained by the Little and Merrimack rivers, the latter separating the Bradford section of town from the rest of Haverhill. The highest point in the city is found on Ayers Hill, a drumlin with two knobs of almost equal elevation of at least 335 feet (102 m), according to the most recent (2011-2012) USGS 7.5-minute topographical map.[41] The city also has several ponds and lakes, as well as three golf courses.

Haverhill is bordered by Merrimac to the northeast, West Newbury and Groveland to the east, Boxford and a small portion of North Andover to the south, Methuen to the southwest, and Salem, Atkinson and Plaistow, New Hampshire, to the north. From its city center, Haverhill is 8 miles (13 km) northeast of Lawrence, 27 miles (43 km) southeast of Manchester, New Hampshire, and 32 miles (51 km) north of Boston.

Points of interest[]

- Main Street Historic District[42]

- The Heights

- Museum of Printing

- Haverhill Stadium (now Trinity Stadium)[43]

- The Buttonwoods Museum – Haverhill Historical Society

- John Greenleaf Whittier Homestead

- Walnut Square School (Haverhill Clock Tower)

- Winnekenni Park Conservation Area, including Winnekenni Castle and Lake Saltonstall

- Downtown Haverhill with 22 restaurants, docks, and two small boardwalks overlooking the Merrimack River

Demographics[]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 2,408 | — |

| 1800 | 2,730 | +13.4% |

| 1810 | 2,682 | −1.8% |

| 1820 | 3,070 | +14.5% |

| 1830 | 3,896 | +26.9% |

| 1840 | 4,336 | +11.3% |

| 1850 | 5,877 | +35.5% |

| 1860 | 9,995 | +70.1% |

| 1870 | 13,092 | +31.0% |

| 1880 | 18,472 | +41.1% |

| 1890 | 27,412 | +48.4% |

| 1900 | 37,175 | +35.6% |

| 1910 | 44,115 | +18.7% |

| 1920 | 53,884 | +22.1% |

| 1930 | 48,710 | −9.6% |

| 1940 | 46,752 | −4.0% |

| 1950 | 47,280 | +1.1% |

| 1960 | 46,346 | −2.0% |

| 1970 | 46,120 | −0.5% |

| 1980 | 46,865 | +1.6% |

| 1990 | 51,418 | +9.7% |

| 2000 | 58,969 | +14.7% |

| 2010 | 60,879 | +3.2% |

| 2019 | 64,014 | +5.1% |

| * = population estimate. Source: United States census records and Population Estimates Program data.[44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54] Source: | ||

As of the census[56] of 2010, there were 60,879 people, 25,576 households, and 14,865 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,846.5 people per square mile (683.1/km2). There were 23,737 housing units at an average density of 712.2 per square mile (275.0/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 88.3% White, 4.5% African American, 0.3% Native American, 1.6% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 4.30% from other races, and 2.6% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino made up 14.5% of the population (5.8% Puerto Rican, 4.6% Dominican, 0.9% Mexican, 0.5% Guatemalan, 0.3% Salvadoran, 0.3% Colombian, 0.2% Cuban). 16.8% were of Irish, 14.6% Italian, 10.1% French, 9.0% English, 7.8% French Canadian and 6.3% American ancestry according to Census 2000.

There were 22,976 households, out of which 33.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 47.0% were married couples living together, 13.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 35.3% were non-families. 28.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.51 and the average family size was 3.11.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 25.7% under the age of 18, 7.7% from 18 to 24, 33.5% from 25 to 44, 20.4% from 45 to 64, and 12.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 90.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 85.7 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $49,833, and the median income for a family was $59,772. Males had a median income of $41,197 versus $31,779 for females. The per capita income for the city was $23,280. About 7.0% of families and 9.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 12.3% of those under age 18 and 10.0% of those age 65 or over.

Government[]

City government

Haverhill operates under a Mayor-council form of government. The current mayor is James J. Fiorentini, who has been mayor since 2004 and was most recently elected in 2019.[57] The City Council has nine members, elected every two years. The most recent election was in 2019.

State representation

Haverhill is represented in the state legislature by officials elected from the following districts:[58]

- Massachusetts Senate's 1st Essex district.[59]

- Massachusetts House of Representatives' 2nd Essex district

- Massachusetts House of Representatives' 3rd Essex district

- Massachusetts House of Representatives' 14th Essex district

- Massachusetts House of Representatives' 15th Essex district

Education[]

Haverhill is the home of the main campus of Northern Essex Community College. Until its closing in 2000, Bradford College provided liberal arts higher education in Haverhill. In 2007, it became the new home of the Zion Bible College, now called Northpoint Bible College. Recently, The University of Massachusetts at Lowell (U-Mass Lowell) has built a satellite campus in Haverhill in the new Harbor Place building, and has begun teaching several courses at Northern Essex Community College. Haverhill completed the reconstruction of the Hunking middle school in the Bradford part of the city. Haverhill is also home to the historic Walnut Square School, first built in 1898 at a cost of $30,000. The school’s tower clock was created by Mr. Edward Howard, a famous clock maker of the 1890’s, at a cost of $1,300.[60]

Public schools in the city are a part of the Haverhill Public Schools District.[61]

Infrastructure[]

Transportation[]

Haverhill lies along Interstate 495, which has five exits throughout the city. The town is crossed by five state routes, including Routes 97, 108, 110, 113 and 125. Routes 108 and 125 both have their northern termini at the New Hampshire state border, where both continue as New Hampshire state routes. Four of the five state routes, except Route 108, share at least a portion of their roadways in the town with each other. Haverhill is the site of six road crossings and a rail crossing of the Merrimack; two by I-495 (the first leading into Methuen), the Comeau Bridge (Railroad Avenue, which leads to the Bradford MBTA station), the Haverhill/Reading Line Railroad Bridge, the Basiliere Bridge (Rte. 125/Bridge St.), the Bates Bridge (Rtes. 97/113 to Groveland), and the Rocks Village Bridge, to West Newbury, just south of the Merrimac town line. In 2010, a project began to replace the Bates Bridge, 60 feet (18 m) downstream, with a modern bridge. The project is expected to take two to three years and cost approximately $45 million.[62]

MBTA Commuter Rail provides service from Boston's North Station with the Haverhill and Bradford stations on its Haverhill/Reading Line. Amtrak provides service to Portland, Maine, and Boston's North Station from the same Haverhill station. Additionally, MVRTA provides local bus service to Haverhill and beyond. The nearest small-craft airport, Lawrence Municipal Airport, is in North Andover. The nearest major airport is Manchester-Boston Regional Airport in Manchester, and the nearest international airport is Logan International Airport in Boston.

Notable people[]

- John Mapes Adams, Medal of Honor recipient during the Boxer Rebellion

- Mabel Albertson (1901–1982), actress

- Louis Alter (1902–1980), songwriter ("Do You Know What It Means to Miss New Orleans?")

- Daniel Appleton (1785–1849), publisher[63]

- William Henry Appleton (1814–1899), Daniel Appleton's son, publisher[63] of Lewis Carroll, Arthur Conan Doyle, Charles Darwin, Thomas Henry Huxley, Herbert Spencer, and John Stuart Mill

- Bailey Bartlett (1750–1830), member of the United States Constitutional Convention

- Alexander Graham Bell (1847–1922), inventor, spent considerable time in Haverhill initially as a tutor to the deaf son of a prominent shoe magnate who later invested in Bell's telephone concept

- John Bellairs (1938–1991), author of gothic horror fiction for children and young adults

- William Berenberg (1915–2005), Harvard University professor and pediatrician

- Tom Bergeron (1955-), television personality, comedian, and game show host.

- Peter Breck (1929–2012), actor[64]

- Isaac Newton Carleton (1832–1902), educator

- Walter Tenney Carleton (1867–1900), businessman

- Stuart Chase (1888–1985), economist

- Tristram Coffin, among the town's first settlers, who later left to settle Nantucket

- Russ Conway (1949–2019), investigative journalist and Elmer Ferguson Memorial Award recipient[65]

- David Crouse, writer

- Andre Dubus III (1959-), novelist and short story writer

- Hannah Duston (1657–1736), colonial heroine, first woman in the United States to be honored with a statue

- Brian Evans, singer and actor

- Frank Fontaine (1920–1978), comedian, Crazy Guggenheim on The Jackie Gleason Show

- Jeff Fraza, boxer and contestant on reality television show The Contender

- Charlotte Fullerton, author and Emmy-winning children's television writer/producer

- Moses Hazen (1733–1803), Continental Army general

- Sylvia Hitchcock, Miss Alabama USA 1967, Miss USA 1967, Miss Universe 1967

- Red Howard (1900–1973), football player

- Dr. Duncan MacDougall, physician whose studies inspired the film 21 Grams

- Rowland H. Macy (1822–1877), merchant

- Louis Burt Mayer (1884-1957) American film producer and co-founder of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios (MGM)

- Karen McCarthy, Missouri politician

- Charles Minot (1810–1866), railroad executive at Erie Railroad

- Bob Montana, Archie Comics co-creator

- William Henry Moody (1853–1917), Supreme Court justice, and prosecutor in the Lizzie Borden trial

- Carlos Peña, Major League Baseball player

- Anthony Purpura (1986–), USA Rugby National Team player

- Effie Alberta Read (c1873-1930), scientist at the US Food and Drug Administration

- Stephen Robert (1940–), former Chairman and CEO of Oppenheimer & Co., former Chancellor of Brown University

- Seth Romatelli, actor, host of Uhh Yeah Dude

- James E. Rothman, notable cell biologist and Nobel Prize winner[66]

- Joseph Ruskin (1924–2013), née Joseph Richard Schlafman, actor, had roles in four Star Trek series and films including The Magnificent Seven and Prizzi's Honor[67]

- Mike Ryan, Major League Baseball player

- Nathaniel Saltonstall (1639–1707), judge at the Salem witch trials

- Jon Shain (1967–), folk musician

- Spider One, née Michael Cummings, musician, brother of Robert Cummings a.k.a. Rob Zombie

- Charles Augustus Strong (1862–1940), philosopher, of the American school of critical realism

- Noah Vonleh, professional basketball player for the Minnesota Timberwolves

- John Greenleaf Whittier (1807–1892), poet; his poem Snow-Bound is set in Haverhill

- Charlotte White (1782–?), first unmarried American woman missionary, arrived India 1816

- Rob Zombie (1965–), born Robert Cummings, musician and founding member of White Zombie, film director, mainly horror genre

See also[]

Notes[]

- ^ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (DP-1): Haverhill city, Massachusetts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 30, 2012.

- ^ The History of Haverhill, Massachusetts by George Wingate Chase, pp. 46, 47

- ^ COCO+CO. (2016-08-21). "How Haverhill Was Really Founded". WHAV. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- ^ George Wingate Chase, History of Haverhill, Massachusetts.

- ^ George Wingate Chase, The History of Haverhill, Massachusetts, p. 46–47, 63–65.

- ^ "History of Universalist Unitarian Church of Haverhill". uuhaverhill.org. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. pp. 152.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Chisholm 1911, p. 81.

- ^ Mason, Amelia (May 1, 2021). "Town's Statue Of Colonial Woman Who Killed Natives Sparks Debate". NPR News. Retrieved 2021-05-05.

- ^ "ExecutedToday.com » 1693: Elizabeth Emerson". Retrieved Apr 29, 2019.

- ^ "Throat Distemper in Haverhill from Essex Antiquarian Vol.3 1899 page 10". Retrieved Apr 29, 2019.

- ^ Kingsbury, J. D. (1883). Memorial History of Bradford, Mass (PDF). C.C. Morse & Son. pp. 119, 120.

- ^ Miller, William Lee (1995). Arguing About Slavery. John Quincy Adams and the Great Battle in the United States Congress. New York: Vintage Books. pp. 430–431. ISBN 0-394-56922-9.

- ^ Arthurs Gazette http://arthursgazette.blogspot.com/2010/02/ejm-was-married-to-lucy-lapham-daughter.html

- ^ "The Great Fire At Haverhill" (PDF). The New York Times. February 20, 1882.

- ^ "Haverhill's Great Loss" (PDF). The New York Times. February 19, 1882.

- ^ Haverhill, MA City Fire, Feb 1882 | GenDisasters ... Genealogy in Tragedy, Disasters, Fires, Floods Archived 2014-11-29 at the Wayback Machine. .gendisasters.com (2009-11-02). Retrieved on 2013-08-02.

- ^ Frederic C. Heath, Social Democracy Red Book. Terre Haute, IN: Debs Publishing Co., 1900; p. 108.

- ^ "A Search For The Real-Life Archie, Betty And Friends Began In Haverhill". www.wbur.org. Retrieved 2019-12-24.https://www.wbur.org/artery/2015/05/30/archie-betty-haverhill-geary

- ^ Regan, Shawn. "Haverhill gets final $1.7 million for parking garage". Eagle-Tribune. Retrieved April 29, 2019.

- ^ Frank A. Gilmore (1895), Historical Sketch of First Parish, Haverhill, Mass, Haverhill, Mass: C.C. Morse & Son, printers, OCLC 15062015, OL 6909262M

- ^ Scholl Center for American History and Culture. "Massachusetts: Individual County Chronologies". Atlas of Historical County Boundaries. Chicago: Newberry Library. Archived from the original on March 5, 2017. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Davies Project. "American Libraries before 1876". Princeton University. Retrieved September 29, 2012.

- ^ Bridgman 1879.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Industries 1886.

- ^ Population of the 100 Largest Cities and Other Urban Places in the United States: 1790 to 1990, U.S. Census Bureau, 1998

- ^ Jump up to: a b Board of Trade 1889.

- ^ "Merrimac Bridge, Spanning Merrimac River on Bridge Street, Haverhill, Essex County, MA". Historic American Engineering Record (Library of Congress). Retrieved September 29, 2012.

- ^ "Outing (magazine)". August 1885. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - ^ "List of Historical Societies in Massachusetts". Old-Time New England. July 1921.

- ^ Works Progress Administration (1939). Guide to Depositories of Manuscript Collections in Massachusetts (Preliminary ed.). Boston: Historical Records Survey. hdl:2027/mdp.39015034759541.

- ^ "History". Rotary Club of Haverhill. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- ^ "HC Media - Investing in our community". HC Media. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ "City of Haverhill Official Website". Archived from the original on March 2003 – via Internet Archive, Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Meet the Mayors". Washington, DC: United States Conference of Mayors. Archived from the original on June 27, 2008. Retrieved March 30, 2013.

- ^ "History". Haverhill: Spotlight Playhouse. Archived from the original on October 22, 2013. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- ^ "Member Directory". Eastern Massachusetts Association of Community Theatres. Archived from the original on October 30, 2013. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Haverhill city, Massachusetts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 30, 2012.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-02-18. Retrieved 2014-03-30.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Main Street Historic District (Haverhill, Massachusetts)

- ^ Haverhill Stadium - About - Google. Plus.google.com (2013-07-24). Retrieved on 2013-08-02.

- ^ "Total Population (P1), 2010 Census Summary File 1". American FactFinder, All County Subdivisions within Massachusetts. United States Census Bureau. 2010.

- ^ "Massachusetts by Place and County Subdivision - GCT-T1. Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1990 Census of Population, General Population Characteristics: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1990. Table 76: General Characteristics of Persons, Households, and Families: 1990. 1990 CP-1-23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1980 Census of the Population, Number of Inhabitants: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1981. Table 4. Populations of County Subdivisions: 1960 to 1980. PC80-1-A23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1950 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. 1952. Section 6, Pages 21-10 and 21-11, Massachusetts Table 6. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1930 to 1950. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1920 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. Number of Inhabitants, by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions. Pages 21-5 through 21-7. Massachusetts Table 2. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1920, 1910, and 1920. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1890 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. Pages 179 through 182. Massachusetts Table 5. Population of States and Territories by Minor Civil Divisions: 1880 and 1890. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1870 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1872. Pages 217 through 220. Table IX. Population of Minor Civil Divisions, &c. Massachusetts. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1860 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1864. Pages 220 through 226. State of Massachusetts Table No. 3. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1850 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1854. Pages 338 through 393. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1950 Census of Population" (PDF). 1: Number of Inhabitants. Bureau of the Census. 1952. Section 6, Pages 21-7 through 21-09, Massachusetts Table 4. Population of Urban Places of 10,000 or more from Earliest Census to 1920. Retrieved July 12, 2011. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ COCO+CO (2019-11-05). "100% Locally Owned Radio Stations". WHAV. Retrieved 2021-04-13.

- ^ "Massachusetts Representative Districts". Sec.state.ma.us. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- ^ Massachusetts General Court, "An Act Establishing Executive Councillor and Senatorial Districts", Session Laws: Acts (2011), retrieved April 15, 2020

- ^ "Welcome to Haverhill, MA". www.cityofhaverhill.com. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ "Haverhill Public Schools". Haverhill Public Schools. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ Tennant, Paul. "New $45M Groveland bridge will ease travel". The Daily News of Newburyport. Retrieved April 29, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Who Was Who in America, Historical Volume, 1607-1896. Marquis Who's Who. 1963.

- ^ Gates, Anita. "Peter Breck, TV Actor Known for 'The Big Valley', Dies at 82." The New York Times, February 10, 2012

- ^ Burt, Bill (August 20, 2019). "Russ Conway, former Eagle-Tribune sports editor and hockey writer, dies at 70". The Eagle Tribune. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2013". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved April 29, 2019.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-01-06. Retrieved 2014-01-06.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Bibliography[]

- The Story of Hannah Dustin

- "The Great Fire at Haverhill" from The New York Times archive

- "Haverhill's Great Loss" from The New York Times archive

- Disaster Genealogy - The Haverhill Fire

- published in 19th century

- Mirick, B L (1832). History of Haverhill. Haverhill: A W Thayer.

- Jeremiah Spofford (1860), "Haverhill", Historical and Statistical Gazetteer of Massachusetts (2nd ed.), Haverhill: E.G. Frothingham

- George Wingate Chase (1861), History of Haverhill, Massachusetts, Haverhill: Pub. by the author, OCLC 11267735, OL 13557017M

- "Haverhill Business Directory". Merrimack River Directory, for 1872 & 1873. Boston: Greenough, Jones. 1872.

- Elias Nason (1874), "Haverhill", Gazetteer of the State of Massachusetts, Boston: B.B. Russell, OCLC 1728892

- Haverhill: Foundation Facts, Haverhill, Mass: Bridgman & Gay, 1879, OCLC 7188408

- Haverhill - Facts of Interest (1880).

- Benjamin L. Mirick (1882), History of Haverhill, Massachusetts, Haverhill: A. W. Thayer, OCLC 6697842, OL 6905779M

- "City of Haverhill", Industries of Massachusetts, New York: International Pub. Co., 1886, OCLC 19803267

- Haverhill, Massachusetts: an Industrial and Commercial Center, Haverhill, Mass: Board of Trade, 1889, OCLC 11378334, OL 13490085M

- White, Daniel (1889). The Descendants of William White, of Haverhill, Mass.

- published in 20th century

- Haverhill and Groveland Directory. Boston. 1902.

- Thomas, Samuel (1904). Whittier-land: A Handbook of North Essex.

- Haverhill (Mass.). Board of Trade. (1905), History of the City of Haverhill, Massachusetts, Haverhill, OCLC 5042345, OL 6603655M

- Charles A. Flagg (1907), "Essex County: Haverhill", Guide to Massachusetts Local History, Salem, Mass.: Salem Press

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911), , Encyclopædia Britannica, 13 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 81

- "Haverhill, Mass.", Automobile Blue Book, Automobile Blue Book Publishing Co., 1917, OCLC 7442840, OL 23461025M

- Arrington, Benjamin F. (1922). Municipal History of Essex County in Massachusetts. Volume 2 - Haverhill. Volume 3 Biographical. Volume 4 Biographical. New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company.

- Charles A. Richmond (1922), Haverhill Strangers' Directory, Haverhill, Mass: Telegram Press, OL 24157599M

- Federal Writers' Project (1937), "Haverhill", Massachusetts: a Guide to its Places and People, American Guide Series, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, hdl:2027/mdp.39015014440781

- published in 21st century

- Regan, Shawn, "Literary Haunts", Eagle-Tribune, October 22, 2006

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Haverhill, Massachusetts. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1921 Collier's Encyclopedia article Haverhill. |

- Haverhill, Massachusetts

- Cities in Massachusetts

- Populated places established in 1640

- Massachusetts populated places on the Merrimack River

- Populated places on the Underground Railroad

- Cities in Essex County, Massachusetts

- 1640 establishments in Massachusetts