Bad (album)

| Bad | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by Michael Jackson | ||||

| Released | August 31, 1987 | |||

| Recorded | January 1985 – July 1987[1] | |||

| Studio | Westlake (Los Angeles)[2] | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 48:40 | |||

| Label |

| |||

| Producer | Quincy Jones | |||

| Michael Jackson chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Bad | ||||

| ||||

Bad is the seventh studio album by American singer and songwriter Michael Jackson. It was released on August 31, 1987, by Epic Records, nearly five years after Jackson's previous album, Thriller (1982). Written and recorded between January 1985 and July 1987, Bad was the third and final collaboration between Jackson and producer Quincy Jones, with Jackson co-producing and composing all but two tracks. With Bad, Jackson departed from his signature groove-based style and high-pitched vocals. The album's edgier sound incorporates pop, rock, funk, R&B, dance, soul, and hard rock styles. Jackson also experimented with newer recording technology, including digital synthesizers and drum machines, resulting in a sleeker and more aggressive sound. Lyrical themes on the album include media bias, paranoia, racial profiling, romance, self-improvement, and world peace. The album features appearances from Siedah Garrett and Stevie Wonder.

One of the most anticipated albums of its time, Bad debuted at number one on the Billboard Top Pop Albums chart, selling over 2 million copies in its first week in the US. The album also reached number one in 24 other countries, including the UK, where it sold 500,000 copies in its first five days and became the country's best-selling album of 1987. It was the best-selling album worldwide of 1987 and 1988. Nine songs were released as official singles, and one as a promotional single. Seven charted in the top 20 on the Billboard Hot 100, including a record-breaking five number ones: "I Just Can't Stop Loving You", "Bad", "The Way You Make Me Feel", "Man in the Mirror" and "Dirty Diana". By 1991 it was the second-best selling album of all time at the time, behind Thriller, having sold 25 million copies worldwide.

The album was promoted with the film, Moonwalker (1988), which included the music videos of songs from the album, including "Speed Demon", "Leave Me Alone", "Man in the Mirror" and "Smooth Criminal". The film became the best-selling home video of all time. The Bad tour, which was Jackson's first solo world tour, grossed $125 million (equivalent to more than $291 million in 2021) making it the highest-grossing solo concert tour of the 1980s. Jackson performed 123 concerts in 15 countries to an audience of 4.4 million including a record seven sold-out shows at Wembley Stadium. It was also Jackson's last tour where he performed in the United States.

With sales of over 35 million copies sold worldwide, Bad is one of the best-selling albums of all time. In 2021, it was certified 11× platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). The album has been named by several publications as one of the greatest albums of all time. It was nominated for six Grammy Awards, winning Best Engineered Recording – Non Classical and Best Music Video (for "Leave Me Alone"). In 1988, Jackson received the first Billboard Spotlight Award, in recognition of the record-breaking chart success on the Billboard Hot 100. For his Bad videos and previous videos throughout the 1980s, Jackson received the MTV Video Vanguard Award. To celebrate its 25th anniversary, the documentary film, Bad 25 (2012), was released on August 31, 2012. A 25th anniversary album, Bad 25 (2012), was also released on September 18, 2012.

Background[]

Jackson's sixth solo album, Thriller, was released in 1982, and by 1984 it was certified 20× platinum for sales of 20 million copies in the United States alone.[6] Jackson was widely considered the most powerful African American in the history of the entertainment industry,[7] whose popularity was comparable only to Elvis Presley in the 1950s and the Beatles in the 1960s.[8] Jackson aimed to sell 100 million copies with his next album.[7]

The years following Thriller were marred by Jackson's rifts with his family and the Jehovah's Witnesses, broken friendships with celebrities, and the pressure of celebrity.[2] He spent 1985 out of the public eye,[7] while reports spread of eccentric behavior and changing appearance, including a more chiselled face, fairer complexion, a perkier nose, and a cleft chin.[9] According to some associates, Jackson was nervous about completing his next album.[2] In 1987, Spin wrote that "in record time, [Jackson] has gone from being one of the most admired of celebrities to one of the most absurd. And the pressure to restore himself in the public eye is paralyzing him."[2]

Production[]

Bad was Jackson's final collaboration with co-producer Quincy Jones, who had produced Off the Wall and Thriller.[10] After Jackson had written a handful of the tracks on Off the Wall and Thriller, producer Jones encouraged him to write more for his followup. Jones recalled: "All the turmoil [in Jackson's life] was starting to mount up, so I said I thought it was time for him to do a very honest album."[11]

For his next album, Jackson wanted to move in a new musical direction, with a harder edge and fiercer sound.[9] According to guitarist Steve Stevens, who featured on Bad, Jackson asked about rock bands including Mötley Crüe.[9] Jackson began recording demos for the anticipated follow-up to Thriller in November 1983 while recording Victory with the Jacksons.[1] He spent much of 1985 to 1987 out of the public eye, writing and recording at his home studio in Encino, Los Angeles, with a group of musicians and engineers including Bill Bottrell known as the "B team".[12] The demos were brought to Westlake Studio to be finished by the "A team", with Jones and engineer Bruce Swedien.[12] Jones said the team would stay up for days on end when they "were on a roll": "They were carrying second engineers out on stretchers. I was smoking 180 cigarettes a day."[11]

Jackson was eager to find innovative sounds and was interested in new music technology.[7] The team made extensive use of new digital synthesizers, including FM synthesis and the Fairlight CMI and Synclavier PSMT synthesizers. They sometimes combined synthesizers to create new sounds.[7] Other instruments include guitars, organs, drums, bass, percussion and saxophones,[13] washboard and digital guitars.[13]

Work was disrupted in July 1984, when Jackson embarked on the Victory Tour with his brothers.[1] Work resumed in January 1985 after the tour ended and after Jackson had recorded "We Are the World".[1] In mid-1985, work was disrupted again so Jackson could prepare for Disney's 4D film experience Captain EO, which featured an early version of the Bad song "Another Part of Me."[1] Studio work resumed in August and continued until November 1986, when Jackson filmed the "Bad" music video.[1] Recording resumed in January 1987, and the album was completed in July.[1]

Jackson wrote a reported 60 songs, and recorded 30, wanting to use them all on a three-disc set.[5] Jones suggested that the album be cut down to a ten-track single LP.[5] Jackson is credited for writing all but two songs;[5] other writing credits include Terry Britten and Graham Lyle for "Just Good Friends" and Siedah Garrett and Glen Ballard for "Man in the Mirror".[10]

Composition and lyrics[]

Bad is musically a heavier and more "aggressive" record than Thriller, with Jackson moving away from the heavy-groove sound and high-pitched vocals which featured on both Off the Wall and Thriller.[12] Bad primarily incorporates pop, rock, funk and R&B,[14][15] but also explores other genres such as soul[16] and hard rock.[17] Stephen Thomas Erlewine of AllMusic noted that Bad moved Jackson "deeper into hard rock, deeper into schmaltzy adult contemporary, deeper into hard dance – essentially taking each portion of Thriller to an extreme, while increasing the quotient of immaculate studiocraft."[17]

The album's song lyrics relate to romance and paranoia, the latter being a recurring theme in Jackson's albums.[17] "Bad" was originally intended as a duet between Jackson and Prince (and Jackson had also planned duets with Diana Ross, Whitney Houston, Aretha Franklin and Barbra Streisand).[5] The song was viewed as a revived "Hit the Road Jack" progression with lyrics that pertain to boasting.[18] "Dirty Diana" was viewed by AllMusic's Stephen Thomas Erlewine as misogynistic[17] and its lyrics, describing a sexual predator, do not aim for the "darkness" of "Billie Jean", instead sounding equally intrigued by and apprehensive of a sexual challenge, while having the opportunity to accept or resist it.[18] "Leave Me Alone" was described as being a "paranoid anthem".[17] "Man in the Mirror" was seen as Jackson going "a step further" and offering "a straightforward homily of personal commitment", which can be seen in the lyrics, "I'm starting with the man in the mirror / I'm asking him to change his ways / And no message could have been any clearer / If you wanna make the world a better place / Take a look at yourself and then make a change."[18]

The lyrics to "Liberian Girl" were viewed as "glistening" with "gratitude" for the "existence of a loved one".[18] Those to "Smooth Criminal" recalled "the popcorn-chomping manner" of "Thriller".[18] The track was thought of as an example of "Jackson's free-form language" that keeps people "aware that we are on the edge of several realities: the film, the dream it inspires, the waking world it illuminates".[18] The music in "I Just Can't Stop Loving You", a duet with Siedah Garrett, consisted mainly of finger snaps and timpani.[18] "Just Good Friends" is a duet with Stevie Wonder;[18] Jones said later: "I made a mistake with ['Just Good Friends']. That didn't work."[11]

Jackson's mother, Katherine Jackson, wanted him to write an R&B song with a shuffle rhythm for the album, which came to be "The Way You Make Me Feel".[13] The song consists of blues harmonies[19] and a jazz-like tone,[13] comparable to the classic Motown sound of the 1960s.[13] The lyrics of "Another Part of Me" deal with being united, as "we".[19] Critics Richard Cromelin (from the Los Angeles Times)[20] and Richard Harrington (from The Washington Post) associated the song's lyrics with the Harmonic Convergence phenomenon that occurred around the time of the album's release, with Harrington highlighting the verse: "The planets are lining up / We're bringing brighter days / They're all in line / Waiting for you / Can't you see? / You're just another part of me".[21]

Release[]

Bad was released on August 31, 1987.[19][22] Described as "the most anticipated album in history" by the Miami Herald.[23] however, it failed to match the sales of Thriller in the US, causing some in the media to label the album a disappointment.[5][24] Michael Goldberg and David Handelman had predicted that "If Bad sells 'only' 10 million copies, that will be more than virtually any other record but could be viewed as a failure for Michael Jackson".[25]

In the United States, it debuted at number one on the Billboard 200, selling around 2 million copies and remained there for six consecutive weeks. In 2021, it was certified 11× platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA).[26][27][28][29][30][31][32]

In the UK, Bad debuted at number one on the UK Albums Chart, selling 500,000 copies in its first five days.[33] It was the country's best-selling album of 1987.[34] In the UK, Bad certified 13 times platinum with sales of 3.9 million, making it Jackson's second best-selling album there.[33] It was certified seven times platinum for the shipment of over 700,000 copies in Canada by the Canadian Recording Industry Association.[35]

Worldwide, The album peaked at number one in 25 countries in total[36] including Austria,[37] Canada,[38] Japan,[39] New Zealand,[40] Norway,[41] Sweden,[42] Switzerland[43] and the UK.[44] It also charted at No. 13 in Mexico[45] and at No. 22 in Portugal.[46] Bad sold 7 million copies worldwide in its first week[47] and 18 million copies in its first year.[48] It was the best-selling worldwide in 1987 and 1988.[49]

In 1988, the IFPI certified Michael Jackson as the top selling artist and Bad as the best selling album worldwide with 17 million of copies.[50] By 1991, it was the second-best-selling album of all time, behind Thriller, having sold 25 million copies worldwide.[51]

In Europe, the 2001 reissue was certified platinum by the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) for the sales of one million units.[52] The album was also certified platinum by the IFPI for the shipment of over 20,000 copies in Hong Kong.[53] Globally, Bad is Jackson's second best-selling album behind Thriller, with sales of 35 million copies.[54][55]

Promotion[]

The marketing strategy for Bad was modeled on that for Thriller.[31] Like the first Thriller single, "The Girl Is Mine", the first Bad single, "I Just Can't Stop Loving You", was a ballad duet, followed by two "more obvious modern pop knockouts" backed by music videos.[31]

A commemorative special on Jackson's life, The Magic Returns, aired on CBS during prime time on the day of the release of Bad. At the end of the documentary, the channel debuted the short film for "Bad", directed by Martin Scorsese and featuring Wesley Snipes.[19] The marketing strategy, mastered by Frank DiLeo among others, also included Jackson producing another mini-movie around the time of the Bad world tour. That film, Moonwalker (1988), included performances of songs from Bad, including "Speed Demon", "Leave Me Alone", "Man in the Mirror" and "Smooth Criminal", the latter two released as sole videos at the end of the film.[56] The film also included the music video for "Come Together", with the song featuring seven years later on HIStory: Past, Present and Future, Book I. It became the best-selling home video of all time.[57]

Sponsored by Pepsi, the Bad tour began in Japan, marking Jackson's first performances there since 1972 with the Jackson 5.[58] Attendance figures for the first 14 dates in Japan totalled a record-breaking 450,000.[59] Jackson performed seven sold-out shows at Wembley Stadium, beating the previous record held by Madonna, Bruce Springsteen and Genesis. The third concert on July 16, 1988, was attended by Diana, Princess of Wales and Prince Charles.[60] Jackson was entered into the Guinness World Records three times from the tour alone. The Bad tour was a major financial success, grossing $125 million.[61][62] Jackson performed 123 concerts in 15 countries to an audience of 4.4 million.[63]

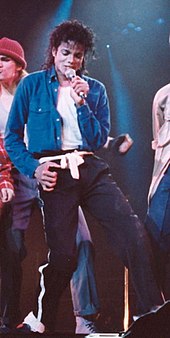

For the Bad era, Jackson wore black outfits decorated with zippers and buckles, similar to his outfit on the Bad album cover.[25] Stevens recalled that when he met Jackson, "I was wearing patent leather, he [Jackson] was wearing penny loafers. I turned him [Jackson] onto the guy who did my clothes."[9] Jackson also grew out his jheri curl over shoulder-length and began wearing eye liner.[9] His androgyny is considered to have increased during the era, which he would maintain for the rest of his life.[64][65]

Singles[]

"I Just Can't Stop Loving You", a duet with Siedah Garrett, was the lead single. It peaked at number one on the Billboard Hot 100 and also reached number one in Belgium, Canada, Ireland, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, the UK and Zimbabwe.[66]

"Bad" reached number one on the Billboard Hot 100, and remained there for two weeks, becoming the album's second number-one single, and Jackson's eighth number one entry on the chart. It also peaked at number one on the Hot R&B Singles, Hot Dance Club Play and Rhythmic chart. Internationally, the song was also commercially successful, charting at the top of the charts in seven other countries including Ireland, Italy, Norway, Spain, and the Netherlands.

"The Way You Make Me Feel" was the third consecutive Billboard Hot 100 number-one and reached number one in Ireland and Spain. "Man in the Mirror" reached number one on Billboard Hot 100 and in Canada and Italy.[citation needed] Jackson performed both songs at the 1988 Grammy Awards.[67] It was nominated for Record of the Year at the next year's 1989 Grammy Awards.[68]

"Dirty Diana" was the record-breaking fifth Billboard Hot 100 number-one single from Bad.[69] Before the start of the Wembley Stadium show during the Bad tour in 1988, Diana, Princess of Wales, who was in attendance, informed Jackson that it was one of her favorite songs.[70]

"Another Part of Me" achieved less success, reaching number 11 on the Billboard Hot 100, but topped the R&B Singles Chart.[71][72] Like Jackson's earlier songs in his career such as "Can You Feel It" and "We Are the World", the lyrics of the song emphasize global unity, love and outreach.[73]

"Smooth Criminal" became the sixth top 10 single on the Billboard Hot 100, peaking at number seven.[71] The song reached number one in Belgium, Iceland, the Netherlands and Spain.[74] Though it was not one of the Billboard Hot 100 number-one singles, in retrospective reviews it has been regarded as one of the best songs on Bad and one of Jackson's signature songs.[75]

Released outside the United States and Canada, "Leave Me Alone" topped the Irish charts[76] and reached the top ten in five other countries.[77] "Leave Me Alone" was Jackson's response to negative and exaggerated rumors about Jackson that frequently appeared in the tabloids post-1985 after the success of Thriller.[78] The music video was the recipient of Best Music Video at the 1990 Grammy Awards.[68]

The album's final single, "Liberian Girl", did not chart on the Billboard Hot 100, but reached the top 20 in various countries and reached number one in Ireland.[79] The song has been sampled and covered by various artists including Chico Freeman, 2Pac and MC Lyte.[80]

Bad became the first album to have five consecutive singles peak at number one on the Billboard Hot 100. In 2011, the record was tied by American singer Katy Perry's Teenage Dream.[81] In the UK, seven of the Bad singles reached the UK top ten which was a record for any studio album for over 20 years.[82]

Covers[]

In 1988, "Weird Al" Yankovic recorded "Fat", a parody of "Bad", which won a Grammy Award for Best Concept Music Video at the 1989 Grammy Awards.[83]

Critical reception[]

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Blender | |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Entertainment Weekly | B+[86] |

| Los Angeles Times | |

| MusicHound R&B | 3.5/5[87] |

| The Philadelphia Inquirer | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| The Village Voice | B+[90] |

Davitt Sigerson from Rolling Stone wrote that "even without a milestone recording like 'Billie Jean', Bad is still a better record than Thriller." He believed the filler, such as "Speed Demon", "Dirty Diana" and "Liberian Girl", made Bad "richer, sexier and better than Thriller's forgettables."[18] In a contemporary review for The New York Times, Jon Pareles called Bad "a well-made, catchy dance record by an enigmatic pop star". He said while nothing on the record compared to "Wanna Be Startin' Somethin'", the music's "concocted synthesizer-driven arrangements" were "clear" and carried "a solid kick".[19] In USA Today, Edna Gundersen called it Jackson's "most polished effort to date," that is "calculated but not sterile."[91]

The Village Voice critic Robert Christgau was also critical. While he felt album's "studio mastery" and Jackson's "rhythmic and vocal power" made for "the strongest and most consistent black pop album in years", he lamented its lack of "genius" in the vein of "Beat It" or "Billie Jean" and panned the lyrical themes: "He's against burglary, speeding, and sex ('Dirty Diana' is as misogynistic as any piece of metal suck-my-cock), in favor of harmonic convergence and changing the world by changing the man in the mirror. His ideal African comes from Liberia. And he claims moonwalking makes him a righteous brother. Like shit."[90]

The Daily Telegraph commented that while Bad was another worldwide commercial success, the album "inevitably failed to match the success of Thriller despite Jackson's massive and grueling world tour",[92] though Rolling Stone commented that "the best way to view" Bad was not as "the sequel to Thriller.[18] Richard Harrington of The Washington Post felt that while the album could not live up to post-Thriller expectations, it would be "considerably fairer to compare" Bad with Off the Wall. His overall opinion on Bad was that it was "a very good record" that is "immaculately produced and with some scintillating vocal performances from Jackson".[93] Richard Cromelin of the Los Angeles Times called Bad "a fair-to-strong array of soul and rock blends", commenting that the record was "not bad" and was more "reminiscent of Off the Wall's uniform strength than Thriller's peaks and valleys". Cromelin felt that it would be "disappointing" if this album's "creative level" is where Jackson wants to stay.[16]

In 1988, Bad was nominated for Grammy Awards for Album of the Year, Best Pop Vocal Performance – Male, Best R&B Vocal Performance – Male, and won for Best Engineered Recording – Non Classical.[94] The following year, it was nominated for Record of the Year for "Man in the Mirror",[95] and in 1990 won for Best Music Video – Short Form (for "Leave Me Alone").[96] "Bad" won an American Music Award for Favorite Soul/R&B Song at the 1988 American Music Awards.[97] At the 1988 Soul Train Music Awards, the album won Best R&B/Soul Album – Male and "Bad" won Best R&B/Soul Single – Male. The following year, "Man in the Mirror" also won Best R&B/Soul Single – Male. At the 1989 Brit Awards, "Smooth Criminal" won British Video of the Year. Following the appraisal of the music videos of the singles from Bad, along with his previous music videos throughout the 1980s, Jackson was awarded the MTV Video Vanguard Award.[98]

Legacy and influence[]

Reappraisals[]

Bad has been credited as defining the sound of "late-80s' pop".[99] The album further set the standard for innovation in music videos following the success of the music videos for "Bad", "Smooth Criminal", "The Way You Make Me Feel" and "Leave Me Alone".[12] A writer for the Miami Herald reflected back on the anticipation for Bad, describing the album's release as being the "most hotly anticipated album in history".[23] In a retrospective review for BBC Music, Mike Diver regarded Bad as a landmark factor of 1980s pop culture: "A multi-million-unit-shifter, Bad was (and remains) as important to 1980s pop culture as the rise of the Walkman, the Back to the Future movies, and the shooting of JR. Like 1982's Thriller, it's an album that appeared to easily find a home within the record collection of rockers and poppers, punks and poets alike." Diver also praised the album for being the "best of the best [of its time]" and an "essential pop masterpiece".[100] Writing for Billboard, Gail Mitchell wrote that Bad is "one of the most important pop albums of the late '80s, and one of the most successful albums in Billboard chart history".[101]

In 2009, VH1 said of the album:

Understandably, the expectations for the album were ridiculously high, and grew even higher after Jackson planned duets with the likes of Prince (on the title track) and Whitney Houston (and Aretha Franklin and Barbra Streisand). None of those collaborations ended up happening, but they only increased the hype for the album. Bad was a deeply personal project for Jackson – he wrote nine of the 11 songs – one that saw him gain further independence and debut a harder-edged look and sound.[5]

In 2009, Jim Farber of the Daily News wrote that Bad "streamlined the quirks" of Jackson's two previous albums to "create his most smooth work of pop to date."[102] Writing for The Root, Matthew Allen claimed that Bad was the start of Jackson's three-year "prime" in his "vocals, songwriting, producing, performing and video output". Allen also regarded the album as "[doubling] down on the edge" of Thriller in both subject matter and instrumental arrangement.[103] Writing for Albumism, Chris Lacy considered Bad possibly being superior to Off the Wall and Thriller: "Comparisons with Off the Wall and Thriller are unimportant, except for this one: Bad is a pure pop masterpiece that stands parallel with—and, at times, eclipses—its classic predecessors." Lacy also stated that Bad set a "new gold standard for pop music and entertainment".[104]

Joseph Vogel was also enthusiastic about the record. "On Bad, Jackson's music is largely about creating moods, visceral emotions, and fantastical scenarios....[with] each song work[ing] as a dream capsule, inviting the listener into a vivid new sound, story, space." He called Bad "a compelling, phantasmagorical album, which a handful of critics recognized from the beginning."[105] According to Jayson Rodriguez of MTV, "following the twin cannons that were Off the Wall and Thriller wouldn't be an easy task for most, but Jackson's follow-up, 1987's Bad, was formidable by all accounts."[24] Rodriguez also felt that Bad was "wrongfully dismissed by critics because it wasn't the sales blockbuster that Thriller was" and that during the Bad era, Jackson's vocal hiccups and stammered "shamone" would become staples in his music that were "heightening and highlighting the emotion of his lyrics."[24] Erika Ramirez of Billboard highlighted "Another Part of Me" and "Man in the Mirror" for showcasing Jackson as a "caring humanitarian" and emphasizing world unity.[106]

21st century appeal[]

25 years after its release, film director Spike Lee claimed that Bad sounds the 'freshest' today compared to other Billboard 200 number-one albums which were released in 1987, such as U2's The Joshua Tree, Bruce Springsteen's Tunnel of Love and Whitney Houston's Whitney: "Go to the charts ... and see what were the top albums 25 years ago, play those albums now and then play Bad, and then see which one still sounds fresh and doesn't sound dated."[107] Following the 30th anniversary of the album's release, Kendall Fisher of E! Online regarded it as having an impact on contemporary artists; "Essentially, [Bad] epitomized the massive influence [Jackson] had on many of today's biggest artists."[108]

American rapper Kanye West claimed that Jackson's outfit in the "Bad" video is "far more influential" than Jackson's outfit in the "Thriller" video. West also said "I almost dress like that [Jackson's outfit in the "Bad" video] today."[109] American rapper Ludacris, who was featured on Canadian singer Justin Bieber's "Baby", said that the music video for the song is "like a 2010 version" of "The Way You Make Me Feel".[110] After the video was released in 2010, MTV said that the video is "the new version" of "The Way You Make Me Feel", also noting that the choreography "uses a few of Jackson's less-suggestive moves."[111]

Rankings[]

In 2003, Bad was ranked number 202 on Rolling Stone magazine's list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time,[112] 203 in a 2012 revised list,[113] and 194 in a 2020 list.[114] In NME's The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time list, Bad was ranked number 204.[115] It was also included in the book titled 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[116] In 2009, VH1 listed Bad at number 43 on their list of 100 Greatest Albums of All Time of the MTV Generation.[117] In 2012, Slant Magazine ranked the album at number 48 on its list of The 100 Best Albums of the 1980s.[118] Billboard ranked Bad at number 138 on its list of the Greatest of All Time Billboard 200 Albums.[119] It was ranked number 30 in Billboard's list of the Greatest of All Time R&B/Hip-Hop Albums, out of 100 albums.[120] On Billboard's list of All 92 Diamond-Certified Albums Ranked From Worst to Best: Critic's Take, it was ranked number 41.[121]

Accolades[]

| Organization | Country | Accolade | Year | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grammy Awards | United States | Best Engineered Recording – Non-Classical for Bruce Swedien (1988) and Best Music Video for "Leave Me Alone" (1990) | 1988/90 | [94][96] |

| American Music Awards | United States | Favorite R&B Song for "Bad" | 1988 | [97] |

| Billboard | United States | Spotlight Award | 1988 | [citation needed] |

| Quintessence Editions | United Kingdom | 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die | 2003 | [116] |

| VH1 | United States | 100 Greatest Albums of All Time of the MTV Generation (Ranked No. 43) | 2009 | [117] |

| Rolling Stone | United States | 500 Greatest Albums of All Time (Ranked No. 194) | 2020 | [114] |

| NME | United Kingdom | The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time (Ranked No. 204) | 2013 | [115] |

| Billboard | United States | Greatest of All Time Billboard 200 Albums (Ranked No. 138) | 2015 | [119] |

Bad 25[]

It was announced on May 3, 2012, that the Estate of Michael Jackson and Epic Records would be releasing a 25th anniversary album of Bad. The album was named Bad 25 and was released on September 18, 2012.[122] Since the release of Bad 25, there has been a discontinuation of the 2001 special edition.

Track listing[]

All tracks written by Michael Jackson, except where noted; all tracks produced by Quincy Jones and co-produced by Jackson.

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Bad" | 4:08 |

| 2. | "The Way You Make Me Feel" | 4:59 |

| 3. | "Speed Demon" | 4:03 |

| 4. | "Liberian Girl" | 3:55 |

| 5. | "Just Good Friends" (with Stevie Wonder; writers: Terry Britten, Graham Lyle) | 4:09 |

| 6. | "Another Part of Me" | 3:55 |

| 7. | "Man in the Mirror" (writers: Siedah Garrett, Glen Ballard) | 5:21 |

| 8. | "I Just Can't Stop Loving You" (with Siedah Garrett) | 4:27 |

| 9. | "Dirty Diana" | 4:42 |

| 10. | "Smooth Criminal" | 4:20 |

| 11. | "Leave Me Alone" (excluded from original vinyl and cassette releases) | 4:41 |

| Total length: | 48:00 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 12. | "Quincy Jones Interview #1" | 4:04 |

| 13. | "Streetwalker" | 5:49 |

| 14. | "Quincy Jones Interview #2" | 2:54 |

| 15. | "Todo Mi Amor Eres Tú" (with Garrett; writers: Jackson, Rubén Blades) | 4:05 |

| 16. | "Quincy Jones Interview #3" | 2:31 |

| 17. | "Spoken Intro to Fly Away" | 0:09 |

| 18. | "Fly Away" | 3:27 |

- Notes

Re-issues of Bad feature a number of changes when compared to the original 1987 release:

- "Bad" – The original mix was replaced with the 7" single mix. The most notable difference is the lack of horns in all the choruses except for the last two. Horns are also missing from the second and third pre-choruses. The rhythm guitar during the choruses is also turned up along with the hi-hats.

- "The Way You Make Me Feel" – The full-length remix used for the single with louder vocals and ad libs added to the end replaced the original album mix.

- "I Just Can't Stop Loving You" omits Michael Jackson's spoken intro.

- "Dirty Diana" is replaced with the single edit of the song.

- "Smooth Criminal" went through two changes on the album. It was remixed to make the kick drum heavier and the bass synth fatter. The quick-sequenced synclavier behind the bass has been rendered mono as well. The first version of this mix left the breathing intact, but was later removed after some time.

- "Leave Me Alone" was not included on the original vinyl nor cassette releases but was included on the CD release and now is included in all releases.

Personnel[]

Personnel as listed in the album's liner notes are:[10]

- Lead and backing vocals: Michael Jackson

- Background vocals: Siedah Garrett (tracks 7–8), The Winans (7), and The Andraé Crouch Choir (7)

- Bass guitar: Nathan East (track 8)

- Hammond organ: Jimmy Smith (track 1)

- Drums: John Robinson (tracks 1–4, 9–10), Miko Brando (3), Ollie E. Brown (3, 5), Leon "Ndugu" Chancler (8), Bill Bottrell (10), Bruce Swedien (5, 10), Humberto Gatica (5)

- Programming: Douglas Getschal (tracks 1–4, 9), Cornelius Mims (5), Larry Williams (11)

- Guitar: David Williams (tracks 1–3, 6, 9–10), Bill Bottrell (3), Eric Gale (2), Danny Hull, Steve Stevens (solo, 9), Dann Huff (7–8), Michael Landau (5), Paul Jackson Jr. (6, 9, 11)

- Trumpet: Gary Grant, Jerry Hey (tracks 1–3, 5–6, 10)

- Sounds engineered: Ken Caillat, and Tom Jones

- Percussion: Paulinho da Costa (tracks 1–5, 8), Ollie E. Brown (2, 7)

- Keyboards: Stefan Stefanovic, Greg Phillinganes (track 7)

- Saxophone: Kim Hutchcroft (tracks 1–3, 5–6, 10), Larry Williams (1–2, 5–6, 10)

- Synclavier (tracks 1–6, 8–10), digital guitar (1), finger snaps (2), sound effects (3): Christopher Currell

- Synthesizer: John Barnes (tracks 1–4, 6, 9–10), Michael Boddicker (1–5, 9–10), Greg Phillinganes (1–3, 5, 8, 11, solo–1), Rhett Lawrence (5–6), David Paich (4, 8), Larry Williams (4–5, 11), Glen Ballard (7), Randy Kerber (7), Randy Waldman (9)

- Piano: John Barnes (track 8), Kevin Maloney (10)

- Rhythm arrangement: Michael Jackson (tracks 1–4, 6, 9–11), Quincy Jones (1, 3–5, 7–8), Christopher Currell (1), John Barnes (4, 6, 9–10), Graham Lyle (5), Terry Britten (5), Glen Ballard (7), Jerry Hey (9)

- Horn arrangement: Jerry Hey (tracks 1–3, 5–6, 10)

- Programming: Larry Williams (tracks 2), Eric Persing (3), Steve Porcaro (4, 8), Casey Young (11)

- Midi saxophone: Larry Williams (track 3)

Charts[]

Weekly charts[]

|

Year-end charts[]

Decade-end charts[]

|

Certifications and sales[]

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Australia (ARIA)[150] | 6× Platinum | 420,000^ |

| Austria (IFPI Austria)[151] | 4× Platinum | 200,000* |

| Brazil | — | 1,000,000[152] |

| Canada (Music Canada)[153] | 7× Platinum | 700,000^ |

| Denmark (IFPI Danmark)[154] | 4× Platinum | 80,000 |

| Finland (Musiikkituottajat)[155] | Gold | 51,287[155] |

| France (SNEP)[156] | Diamond | 1,507,900[157] |

| Germany (BVMI)[158] | 4× Platinum | 2,000,000^ |

| Hong Kong (IFPI Hong Kong)[159] | Platinum | 20,000* |

| India | — | 200,000[160] |

| Israel[161] | Gold | 20,000[161] |

| Italy | — | 1,000,000[162] |

| Japan (RIAJ)[163] | Gold | 100,000^ |

| Latvia (LaMPA)[164][unreliable source?] | 14× Platinum | |

| Mexico (AMPROFON)[165] | Platinum+Gold | 350,000^ |

| Netherlands (NVPI)[167] | Platinum | 500,000[166] |

| New Zealand (RMNZ)[168] | 9× Platinum | 135,000^ |

| Norway (IFPI Norway)[169] | Platinum | 100,000[169] |

| Portugal (AFP)[169] | Gold | 20,000^ |

| Singapore 1987 sales |

— | 30,000[170] |

| Singapore (RIAS)[171] | Gold | 5,000* |

| Spain (PROMUSICAE)[172] | 3× Platinum | 300,000^ |

| Sweden (GLF)[173] | 2× Platinum | 200,000^ |

| Switzerland (IFPI Switzerland)[169] | 2× Platinum | 100,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[175] | 13× Platinum | 4,140,000[174] |

| United States (RIAA)[26] | 11× Platinum | 11,000,000 |

| Summaries | ||

| Europe (IFPI)[176] For sales in 2009 |

Platinum | 1,000,000* |

| Worldwide | — | 35,000,000[54] |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

See also[]

- Bad (tour)

- Bad 25

- List of best-selling albums

- List of best-selling albums in the United States

- List of best-selling albums in France

- List of best-selling albums in Germany

- List of best-selling albums in Italy

- List of best-selling albums in the United Kingdom

- List of Top 25 albums for 1987 in Australia

- List of Billboard 200 number-one albums of 1987

- List of number-one albums of 1987 (Canada)

- List of number-one albums from the 1980s (New Zealand)

- List of UK Albums Chart number ones of the 1980s

- Michael Jackson albums discography

- Even Worse

Notes[]

References[]

Citations[]

- ^ a b c d e f g Smallcombe 2016, pp. 220–296.

- ^ a b c d Troupe, Quincy (June 25, 2014). "Michael Jackson's 1987 Cover Story: 'The Pressure to Beat It'". Spin. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- ^ Sullivan, Steve (2017). Encyclopedia of Great Popular Song Recordings. 3 & 4. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-5449-7.

- ^ a b Lecocq, Richard; Allard, François (2018). "Bad". Michael Jackson All the Songs: The Story Behind Every Track. London, England: Cassell. ISBN 9781788400572.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Michael Jackson's Life & Legacy: The Eccentric King of Pop (1986–1999)". VH1. June 7, 2009. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011.

- ^ "Gold & Platinum: Michael Jackson – Thriller". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Vogel, Joseph (September 10, 2012). "How Michael Jackson Made 'Bad'". The Atlantic. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- ^ Jones, Jel D. Lewis (2005). Michael Jackson, the King of Pop: The Big Picture: the Music! the Man! the Legend! the Interviews: An Anthology. Amber Books. p. 48. ISBN 0-9749779-0-X.

- ^ a b c d e Appel, Stacey (2012). Michael Jackson Style. Omnibus Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-85712-787-7.

- ^ a b c Bad: Special Edition (booklet). Epic Records. 2001.

- ^ a b c Leight, Elias (August 30, 2017). "Quincy Jones Looks Back on the Making of Michael Jackson's 'Bad'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Murph, John (September 19, 2012). "Michael Jackson's 'Bad' Just Wasn't That Good". The Atlantic. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Lecocq, Richard; Allard, François (2018). "Bad". Michael Jackson All the Songs: The Story Behind Every Track. London, England: Cassell. ISBN 9781788400572.

- ^ Gee, Catherine (November 30, 2012). "Michael Jackson: how Thriller and Bad changed music". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ McNulty, Bernadette (June 26, 2009). "Michael Jackson's music: the solo albums". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- ^ a b Cromelin, Richard (August 31, 1987). "Michael Jackson has a good thing in 'Bad'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 15, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Michael Jackson – Bad". AllMusic. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Sigerson, Davitt (October 22, 1987). "Michael Jackson – Bad". Rolling Stone. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Pareles, Jon (August 31, 1987). "Pop: Michael Jackson's 'Bad,' Follow-Up to a Blockbuster". The New York Times. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

- ^ a b Cromelin, Richard (December 13, 1987). "Unsilent Nights. . . : Four Stars Being Best, a Guide to the Top 40". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ Harrington, Richard (August 31, 1987). "Jackson's 'Bad' Looking Good". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ^ Campbell 1993, p. 153.

- ^ a b "A Look Back". Miami Herald. June 26, 2009. Retrieved February 18, 2010.

- ^ a b c Rodriguez, Jayson (June 25, 2009). "Michael Jackson's Musical Legacy, From the Jackson 5 to Invincible". MTV. Retrieved February 8, 2010.

- ^ a b Goldberg, Michael; Handelman, David (September 24, 1987). "Is Michael Jackson For Real?". Rolling Stone. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- ^ a b "American album certifications – Michael Jackson – Bad". Recording Industry Association of America.

- ^ McIntyre, Hugh (March 1, 2017). "There Are Now 22 Artists with More Than One Diamond Album". Forbes. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- ^ Grein, Paul (November 6, 1987). "'Bad' Sales Not Bad, but Some Hoped for More". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 20, 2021.

- ^ a b "Billboard 200 – Week of September 26, 1987". Billboard. September 26, 1987. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ Caulfield, Keith (January 6, 2010). "Taylor Swift Edges Susan Boyle For 2009's Top-Selling Album". Billboard. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ a b c Unterberger, Andrew; Christman, Ed (August 31, 2017). "How Michael Jackson's 'Bad' Became the First Album to Notch Five Billboard Hot 100 No. 1s". Billboard. Retrieved December 19, 2018.

- ^ Grein, Paul (July 16, 1988). "Album Chart Has Big 'Appetite' For Metal; 'Dirty Dancing' Marks Another Milestone" (PDF). Billboard. Vol. 100 no. 29. p. 6. ISSN 0006-2510.

- ^ a b "Certified Awards". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved February 8, 2010.

- ^ "Gallup Year End Charts 1987: Albums". Record Mirror. January 23, 1988. p. 37.

- ^ "Gold/Platinum". Music Canada. Retrieved May 27, 2014.

- ^ "Michael Jackson Feted As Top Artist of Decade After Selling 110 Million Discs". Jet. Vol. 77 no. 22. March 12, 1990. p. 60. ISSN 0021-5996.

- ^ a b "Austriancharts.at – Michael Jackson – Bad" (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ a b "Top RPM Albums: Issue 0880". RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- ^ a b "Bad". Ranking.oricon.co.jp (in Japanese). Retrieved February 8, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ a b "Charts.nz – Michael Jackson – Bad". Hung Medien. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ a b "Norwegiancharts.com – Michael Jackson – Bad". Hung Medien. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ a b "Swedishcharts.com – Michael Jackson – Bad". Hung Medien. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ a b "Swisscharts.com – Michael Jackson – Bad". Hung Medien. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ a b "Michael Jackson | Artist | Official Charts". UK Albums Chart. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ a b "Mexicancharts.com – Michael Jackson – Bad". Hung Medien. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ a b "Portuguesecharts.com – Michael Jackson – Bad". Hung Medien. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ Stockdale, Charles; Harrington, John; Andrews, Colman (April 10, 2019). "100 Best Pop Albums of All Time". 24/7 Wall St. Retrieved October 13, 2019.

- ^ Harrington, Richard (October 9, 1988). "Prince Michael Jackson Two Paths to the Top of Pop". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- ^ "Jackson tour on its way to U.S." San Jose Mercury News. January 12, 1988. Retrieved July 5, 2010.

- ^ "1993 World Music Awards: Artist Citations" (PDF). Billboard. Vol. 105 no. 23. June 5, 1993. p. 63. ISSN 0006-2510.

- ^ Citron, Alan; Philips, Chuck (March 21, 1991). "Michael Jackson Agrees to Huge Contract with Sony". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- ^ "Michael Jackson: Albumi" (in Finnish). International Federation of the Phonographic Industry. Archived from the original on August 4, 2016. Retrieved February 8, 2010.

- ^ "Hong Kong sales certification". IFPI Hong Kong. 1988. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2014.

- ^ a b Stevens, Tom (August 14, 2017). "Michael Jackson's Bad at 30: share your favourite albums of 1987". The Guardian. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- ^ Kaufman, Gil (November 5, 2010). "Michael Jackson's New Album Cover Decoded". MTV. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- ^ "Review: 'Moonwalker'". Variety. December 31, 1987. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- ^ O'Toole, Kit (2015). Michael Jackson FAQ: All That's Left to Know About the King of Pop. Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-1-4803-7106-4.

- ^ Campbell 1993, p. 186.

- ^ Campbell 1993, p. 208.

- ^ Campbell 1993, p. 217.

- ^ Brooks 2002, p. 81.

- ^ Grant 2009, pp. 104–105.

- ^ "Michael's Last Tour". Ebony. Vol. 44 no. 6. April 1989. pp. 142–153. ISSN 0012-9011.

- ^ "Voice Writers Wrangle Over Michael Jackson in 1987". The Village Voice. June 26, 2009. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ "Michael Jackson: a profile". The Daily Telegraph. June 26, 2009. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ Halstead, Craig; Cadman, Chris (2003). Jacksons Number Ones. Authors OnLine. p. 171. ISBN 0-7552-0098-5.

- ^ "Jackson, Prince lose out at 30th Grammy Awards". Star Tribune. March 3, 1988. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ^ a b "Michael Jackson". The Recording Academy. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ "The Hot 100 – Week of July 2, 1988". Billboard. July 2, 1988. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ Jones 2005, p. 226.

- ^ a b "Bad – Awards". AllMusic. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ "The Hot 100 – September 10, 1988". Billboard. July 2, 1988. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ McCarthy, James (2011). Michael Jackson: Uncensored on the Record. Coda Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1906783372.

- ^ "Michael Jackson – Smooth Criminal" (in Dutch). Ultratop. Hung Medien. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ "50 Best Michael Jackson Songs". Rolling Stone. June 23, 2014. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- ^ "The Irish Charts – All there is to know". Irishcharts.ie. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ^ "Michael Jackson – Leave Me Alone" (in Dutch). Ultratop. Hung Medien. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ Rodman, Sarah (June 26, 2009). "Michael Jackson, pop's uneasy king, dead at 50". The Boston Globe. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- ^ "Michael Jackson – Liberian Girl" (in Dutch). Ultratop. Hung Medien. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- ^ Josephs, Brian (August 29, 2018). "The Best Michael Jackson Samples". Complex. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- ^ Trust, Gary (August 17, 2011). "Katy Perry Makes Hot 100 History: Ties Michael Jackson's Record". Billboard. Retrieved June 26, 2017.

- ^ Renshaw, David (April 23, 2013). "Calvin Harris' album '18 Months' beats Michael Jackson's chart record". NME. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ "Michael Jackson Remembered: 'Weird Al' Yankovic on Imitation as Flattery". Rolling Stone. July 9, 2009. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ^ "Michael Jackson: Bad". Blender. April 2007. Archived from the original on July 22, 2009. Retrieved October 3, 2018.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (2011). "Jackson, Michael". The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th concise ed.). Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-85712-595-8.

- ^ Greenblatt, Leah (July 3, 2009). "Michael Jackson's albums". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ Graff, Gary; du Lac, Josh Freedom; McFarlin, Jim, eds. (1998). "Michael Jackson". MusicHound R&B: The Essential Album Guide. Visible Ink Press. ISBN 1-5785-9026-4.

- ^ Tucker, Ken (September 6, 1987). "Michael Jackson's adventurous mode". The Philadelphia Inquirer.

- ^ Pareles, Jon (2004). "Michael Jackson". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon & Schuster. pp. 414–15. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- ^ a b Christgau, Robert (September 29, 1987). "Consumer Guide". The Village Voice. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ Gundersen, Edna (August 31, 1987). "The ever-changing Jackson, Michael jumps back and he's super 'Bad'". USA Today.

- ^ "Video: Michael Jackson's weird and wonderful life". The Daily Telegraph. June 26, 2009. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- ^ Harrington, Richard (August 31, 1987). "Article: Jackson's 'Bad': Looking Good; Not a 'Thriller' but It's Full of Flash". The Washington Post. HighBeam Research. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved February 7, 2010.

- ^ a b "30th Grammy Awards – 1988". Rock on the Net. Retrieved February 8, 2010.

- ^ "30th Grammy Awards – 1989". Rock on the Net. Retrieved February 8, 2010.

- ^ a b "32nd Grammy Awards – 1990". Rock on the Net. Retrieved February 8, 2010.

- ^ a b "Winners Database: Michael Jackson". American Music Awards. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- ^ Taraborrelli, J. Randy (2009). Michael Jackson: The Magic, the Madness, the Whole Story. Pan Books. ISBN 978-0-330-51565-8.

- ^ Schonfeld, Zach (August 31, 2017). "Michael Jackson's 'Bad' at 30: Every song, ranked from best to worst". Newsweek. Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- ^ Diver, Mike (2012). "Michael Jackson Bad 25 Review". BBC Music. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ^ Mitchell, Gail (August 31, 2017). "Michael Jackson's 'Bad': Quincy Jones, Wesley Snipes & Other Collaborators Tell the Stories of the Album's Five No. 1 Singles". Billboard. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- ^ Farber, Jim (June 26, 2009). "For Michael Jackson, the beat went on: after 'Thriller,' hits kept coming". Daily News. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ Allen, Matthew (August 18, 2017). "Michael Jackson's Bad: 30 Years Ago the King of Pop Hit His Prime ... so Why Is That Album Underrated?". The Root. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- ^ Lacy, Chris (August 29, 2017). "Tribute: Celebrating 30 Years of Michael Jackson's 'Bad'". Albumism. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ^ Vogel, Joseph (2012). Man in the Music: The Creative Life and Work of Michael Jackson. New York: Sterling. p. 114. ISBN 978-1-40277-938-1.

- ^ Ramirez, Erika (August 31, 2012). "Michael Jackson's 'Bad' at 25: Classic Track-by-Track Review". Billboard. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- ^ Markman, Rob (August 31, 2012). "Michael Jackson's Bad: 25 Years Later, Does It Hold Up?". MTV. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ^ Fisher, Kendall (August 31, 2017). "Michael Jackson's Bad Album Turns 30: How the King of Pop Influenced Today's Biggest Artists". E! Online. Retrieved November 17, 2019.

- ^ "Kanye West, Chris Brown, & Mariah Carey Celebrate Michael Jackson's Legacy on 'Bad 25' Special". Rap-Up. November 23, 2012. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- ^ Vena, Jocelyn (February 3, 2010). "Justin Bieber Happy to Leave the Rapping to Ludacris". MTV. Archived from the original on February 6, 2010. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ^ Vena, Jocelyn (February 19, 2010). "Justin Bieber Bowls with Drake, Ludacris in 'Baby' Video". MTV. Archived from the original on March 15, 2010. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ^ "The RS 500 Greatest Albums of All Time (1–500)". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on January 15, 2007.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. May 31, 2012. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- ^ a b "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. September 22, 2020. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- ^ a b Barker, Emily (October 24, 2013). "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time: 300–201". NME. Retrieved January 8, 2020.

- ^ a b "1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die". Quintessence Editions Ltd. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015.

- ^ a b "VH1 – Greatest Albums Ever". MTV. Archived from the original on March 10, 2009.

- ^ "The 100 Best Albums of the 1980s". Slant Magazine. March 5, 2012. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- ^ a b "Greatest of All Time Billboard 200 Albums". Billboard. Archived from the original on October 1, 2016. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ "Greatest of All Time Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums". Billboard. Retrieved January 8, 2020.

- ^ Unterberger, Andrew (September 29, 2016). "All 92 Diamond-Certified Albums Ranked from Worst to Best: Critic's Take". Billboard. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ^ "25th Anniversary of Michael Jackson's Landmark Album Bad Celebrated with September 18 Release of New Bad 25 Packages". Sony Music Entertainment. May 21, 2012. Retrieved June 30, 2012 – via Michaeljackson.com.

- ^ Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992. St Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- ^ "ABPD CD – TOP 10 Semanal" (in Portuguese). Associação Brasileira dos Produtores de Discos. Archived from the original on November 12, 2014.

- ^ "Czech Albums – Top 100". ČNS IFPI. Note: On the chart page, select 200929 on the field besides the word "Zobrazit", and then click over the word to retrieve the correct chart data. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ "Danishcharts.dk – Michael Jackson – Bad". Hung Medien. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ "Italy's Top Ten" (PDF). Cash Box. Vol. LI no. 21. November 14, 1987. p. 18.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – Michael Jackson – Bad" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ a b "Les Albums (CD) de 1987 par InfoDisc". InfoDisc (in French). Archived from the original on February 1, 2016.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – Michael Jackson – Bad" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ "Oficjalna lista sprzedaży :: OLiS - Official Retail Sales Chart". OLiS. Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ "Spanishcharts.com – Michael Jackson – Bad". Hung Medien. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ "Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums – Week of October 3, 1987". Billboard. October 3, 1987. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ "Jahreshitparade 1987" (in German). Austriancharts.at. Hung Medien. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- ^ "Top 100 Albums of 1987". RPM. Vol. 47 no. 12. Library and Archives Canada. December 26, 1987. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- ^ "Top 100 Albums – Jahrescharts – 1987". Offiziellecharts.de (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Archived from the original on May 9, 2015.

- ^ 1987年間アルバムヒットチャート [Japanese Year-End Albums Chart 1987] (in Japanese). Oricon. Retrieved May 12, 2015 – via Entamedata.web.fc2.com.

- ^ "Schweizer Jahreshitparade 1987". Hitparade.ch (in German). Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Chart Archive – 1980s Albums". Everyhit.com. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ "The CASH BOX Year-End Charts: 1987". Cash Box. Archived from the original on September 18, 2012.

- ^ "ARIA Top 100 Albums for 1988". Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- ^ "Jahreshitparade 1988" (in German). Austriancharts.at. Hung Medien. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- ^ "Top 100 Albums – Jahrescharts – 1988". Offiziellecharts.de (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Archived from the original on May 9, 2015.

- ^ "Top Selling Albums of 1987". Nztop40.co.nz. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- ^ "Schweizer Jahreshitparade 1988". Hitparade.ch (in German). Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- ^ "Billboard 200 Albums: 1988". Billboard. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ^ "Year-End Charts – Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums: 1988". Billboard. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- ^ "The CASH BOX Year-End Charts: 1988". Cash Box. Archived from the original on October 7, 2012.

- ^ "Bestenlisten – 80er-Album" (in German). Austriancharts.at. Hung Medien. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2009 Albums" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association.

- ^ "Austrian album certifications – Michael Jackson – Bad" (in German). IFPI Austria.

- ^ Cezimbra, Marcia (September 6, 1991). "Jacko está de volta". Jornal do Brasil (in Portuguese). p. 8. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- ^ "Canadian album certifications – Michael Jackson – Bad". Music Canada.

- ^ "Danish album certifications – Michael Jackson – Bad". IFPI Danmark. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- ^ a b "Michael Jackson" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland.

- ^ "Les Albums Certifiés "Diamant"". InfoDisc (in French). Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- ^ "Les Meilleures Ventes de CD / Albums "Tout Temps"". InfoDisc (in French). Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ "Gold-/Platin-Datenbank (Michael Jackson; 'Bad')" (in German). Bundesverband Musikindustrie.

- ^ "IFPIHK Gold Disc Award − 1988". IFPI Hong Kong. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ Cobo, Leila (July 2, 2009). "Michael Jackson Remains a Global Phenomenon". Billboard. Retrieved February 8, 2014.

- ^ a b "Jackson Awarded for Israeli Success" (PDF). Music & Media. Vol. 10 no. 45. November 6, 1993. p. 6. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- ^ "E' Claudio Baglioni il Jackson italiano". La Stampa (in Italian). May 12, 1995. Retrieved February 8, 2014.

- ^ "Japanese album certifications – マイケル・ジャクソン – Bad" (in Japanese). Recording Industry Association of Japan. Select 1994年11月 on the drop-down menu

- ^ "International Latvian Certification Awards from 1998 to 2001". Latvian Music Producers Association. 1999. Retrieved June 12, 2019 – via Directupload.

- ^ "Certificaciones" (in Spanish). Asociación Mexicana de Productores de Fonogramas y Videogramas. Retrieved March 29, 2021. Type Michael Jackson in the box under the ARTISTA column heading and Bad in the box under TÍTULO

- ^ "Een ster in het land van lilliputters". Trouw (in Dutch). October 29, 2001. Retrieved February 8, 2014.

- ^ "Dutch album certifications – Michael Jackson – Bad" (in Dutch). Nederlandse Vereniging van Producenten en Importeurs van beeld- en geluidsdragers. Enter Bad in the "Artiest of titel" box.

- ^ "New Zealand album certifications – Michael Jackson – Bad". Recorded Music NZ.

- ^ a b c d "The European Best Sellers of 1987" (PDF). Music & Media. Vol. 4 no. 51/52. December 26, 1987. pp. 42–46.

- ^ Leo, Christie (November 7, 1987). "'Bad' Gets Good Marks in Singapore" (PDF). Billboard. Vol. 99 no. 45. p. 73. Retrieved February 18, 2021 – via World Radio History.

- ^ "Singapore album certifications – Michael Jackson – Bad". Recording Industry Association Singapore. Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- ^ Salaverri, Fernando (September 2005). Sólo éxitos: año a año, 1959–2002 (in Spanish) (1st ed.). Spain: Fundación Autor-SGAE. ISBN 84-8048-639-2.

- ^ "Guld- och Platinacertifikat − År 1987−1998" (PDF) (in Swedish). IFPI Sweden. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 17, 2011.

- ^ Copsey, Rob (October 13, 2018). "The UK's biggest studio albums of all time". Official Charts Company. Retrieved October 13, 2018.

- ^ "British album certifications – Michael Jackson – Bad". British Phonographic Industry.

- ^ "IFPI Platinum Europe Awards – 2009". International Federation of the Phonographic Industry.

Works cited[]

- Brooks, Darren (2002). Michael Jackson: An Exceptional Journey. Chrome Dreams. ISBN 1-84240-178-5.

- Campbell, Lisa D. (1993). Michael Jackson: The King of Pop. Branden Books. ISBN 978-0-82831-957-7.

- Dyson, Michael Eric (1993). Reflecting Black: African-American Cultural Criticism. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-2141-1.

- Grant, Adrian (2009). Michael Jackson: The Visual Documentary. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-84938-261-8.

- Smallcombe, Mike (2016). Making Michael. Clink Street Publishing. ISBN 978-1-91078-251-4.

- Taraborrelli, J. Randy (2004). The Magic and the Madness. Terra Alta, WV: Headline. ISBN 0-330-42005-4.

External links[]

- Bad at Discogs (list of releases)

- 1987 albums

- Michael Jackson albums

- CBS Records albums

- Epic Records albums

- Albums arranged by Quincy Jones

- Albums produced by Michael Jackson

- Albums produced by Quincy Jones

- Albums recorded at Westlake Recording Studios

- Grammy Award for Best Engineered Album, Non-Classical