Baranagar, Murshidabad

Baranagar | |

|---|---|

Village | |

Baranagar Location in West Bengal, India | |

| Coordinates: 24°15′20″N 88°14′30″E / 24.2556°N 88.2416°ECoordinates: 24°15′20″N 88°14′30″E / 24.2556°N 88.2416°E | |

| Country | |

| State | West Bengal |

| District | Murshidabad |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Bengali, English |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| Telephone/STD code | 03482 |

| Vehicle registration | WB |

| Lok Sabha constituency | Murshidabad |

| Vidhan Sabha constituency | Murshidabad |

| Website | murshidbad |

Baranagar (also referred to as Baronagar, Barnagar) is a village in the Murshidabad-Jiaganj CD block in the Lalbag subdivision of Murshidabad district in the state of West Bengal, India.

Geography[]

M: municipal town, CT: census town, R: rural/ urban centre, H: historical place

Owing to space constraints in the small map, the actual locations in a larger map may vary slightly

Location[]

Baranagar is located at 24°15′20″N 88°14′30″E / 24.2556°N 88.2416°E.

Area overview[]

While the Lalbag subdivision is spread across both the natural physiographic regions of the district, Rarh and Bagri, the Domkal subdivision occupies the north-eastern corner of Bagri. In the map alongside, the Ganges/ Padma River flows along the northern portion. The border with Bangladesh can be seen in the north and the east. Murshidabad district shares with Bangladesh a porous international border which is notoriously crime prone (partly shown in this map). The Ganges has a tendency to change course frequently, causing severe erosion, mostly along the southern bank.[1][2][3][4] The historic city of Murshidabad, a centre of major tourist attraction, is located in this area. In 1717, when Murshid Quli Khan became Subahdar, he made Murshidabad the capital of Subah Bangla (then Bengal, Bihar and Odisha).[5] The entire area is overwhelmingly rural with over 90% of the population living in the rural areas.[6]

Note: The map alongside presents some of the notable locations in the subdivisions. All places marked in the map are linked in the larger full screen map.

Demographics[]

According to the 2011 Census of India, Baranagar had a total population of 1,721, of which 913 (53%) were males and 808 (47%) were females. Population in the age range 0–6 years was 202. The total number of literate persons in Baranagar was 1,212 (79.79% of the population 6 years).[7]

Culture[]

About Baranagar, the book writes,” Opposite to Sadeqbagh, on the west bank of the river, about a couple of miles from the Azimganj Rail-way Station, is Barnagar, formerly the residence of Rai Udai Naraen of Rajshye. Here lived, on the banks of the sacred Bhagirathee, the famous Rani Bhowani, who spent enormous sums of money in founding endowments and charitable institutions and gave away rent free lands to numerous Brahmins. She was a most talented lady, possessing extraordinary business habits. Her piety and devotion were unparalled and her good name as a pious, devout, liberal and actively benevolent lady has become a household word in Bengal.”

The text appearing after the image reads, “In the early widowhood of her daughter, Tara, she experienced a great misfortune. On the occasion of her marriage, Rani Bhowani had consulted the best Pandits and astrologers of Benares, Mithila, the Deccan &c. They fixed a most auspicious day, when Taras marriage took place. But her husband died shorty after. When the decision of the learned men were reviewed, it was found that they had omitted to notice the Saptashalaka, which took away from the day its auspicious character and made it a most evil day for the performance of marriage. The temples of Bhubaneswar Siva and Rajrajeswari built by Rani Bhowani and of Gopal built by Tara, still exist, the workmanship being- excellent. Her son, Rajah Ram Krishna, was a devout Sakta.”

David J. McCutchion focuses on several temples at Baranagar:[8]

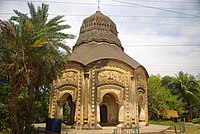

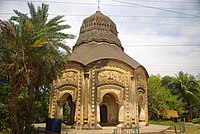

- Char Bangla Temples are mentioned as ek-bangla structures with triple entrance, measuring 31’ x 15–16.5’. The northern temple is dated 1760. Two of the temples have rich terracotta façade, one has incised plaster and the fourth one is plain.

- Panchanan Siva temple, is an 18th-century ek-bangla structure with triple entrance, with renovated terracotta designs.

- The Gangesvara temple, is a mid-18th century standard jor bangla, measuring 22’ 6” x 26’ 3” with rich terracotta façade.

- The Ramonathesvara temple, is a large char chala temple on a square base with a single entrance, measuring around 19’ square, built in 1741, having rich terracotta façade.

According to the List of Monuments of National Importance in West Bengal the Bhavaniswar Mandir and the Char Bangla group of four Siva Mandirs are ASI listed monuments.[9]

Rani Bhabani (1716-1795) was wife of Raja Ramakanta, zamindar of Natore, in Rajshahi district, now in Bangladesh. After she became a widow at the age of 32, she ran her zamindari smoothly and earned fame for her philanthropic activities. According to Shyamal Chaterji, researcher on Hindu iconography, “It is said that Rani Bhavani wanted to build 108 temples here at Baronagar on the shore of the Ganges to lift the status of this settlement to that of Varanasi. She stopped at 107; I have not heard any story about the reason.” Only a few of the temples are in good shape.[10]

Baranagar picture gallery[]

One of the Char Bangla Temples

Terracotta relief at a Char Bangla temple. It is shows the Last prayer of Ravana, the most famous among the wall-reliefs of Baronagar.

Bhavaniswar Temple

Stucco work at Bhavaniswar Temple

Gangeswar Temple

Terracotta decoration at Gangeswar Temple

Panchamukhi Siva Temple

Terracotta decoration at Panchamukhi Shiva temple.

Transport[]

Poradanga halt railway station, on the Barharwa–Azimganj–Katwa loop, is located nearby.[11]

Country boats are available for travel between Ajimganj and Baranagar. [12]

References[]

- ^ "Types and sources of floods in Murshidabad, West Bengal" (PDF). Swati Mollah. Indian Journal of Applied Research, February 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ^ "District Census Handbook: Murshidabad, Series 20 Part XII A" (PDF). Physiography, Page 13. Directorate of Census Operations, West Bengal, 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- ^ "Murshidabad". Geography. Murshidabad district authorities. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- ^ "Child labour, illness & lost childhoods, India's tobacco industry". Edge of Humanity Magazine, 27 December 2020. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ^ "District Gazeteer" (PDF). (in Bengali) Chapter 3: History. Murshidabad District Administration. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "District Census Handbook, Murshidabad, Series 20, Part XII B" (PDF). District Primary Census Abstract page 26. Directorate of Census Operations West Bengal. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ "District Census Handbook, Murshidabad, Series 20, Part XII B" (PDF). Rural PCA-C.D. blocks wise Village Primary Census Abstract, location no. 314,912, page 316-317. Directorate of Census Operations West Bengal. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ McCutchion, David J., Late Mediaeval Temples of Bengal, first published 1972, reprinted 2017, pages 26,28, 30. The Asiatic Society, Kolkata, ISBN 978-93-81574-65-2

- ^ "List of Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains of West Bengal - Archaeological Survey of India". Item no. 110 and 111. ASI. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ "Art and architecture of the temples at Baronagar, Murshidabad". Shyamal Chaterji. Chitralekha Journal of Art & Design. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ "Poradanga Halt". IndiaRailInfo. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ "The Char Bangla Temples of Murshidabad, West Bengal". Ancient Inquiries, 5 January 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

External links[]

![]() Murshidabad travel guide from Wikivoyage

Murshidabad travel guide from Wikivoyage

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Baronagar. |

- Villages in Murshidabad district