Battle of Sisak

| Battle of Sisak | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of "Long War" Hundred Years' Croatian-Ottoman War | |||||||

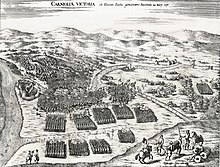

Christians Before Sisak, Croatia A.D. 1593 (from book by Hieronymus Oertel, Nuremberg 1665) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 12,000[1]–16,000[2][3] |

4,300–5,800 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 8,000[2][7] killed or drowned | 50[7]–500[8] | ||||||

The Battle of Sisak[9] was fought on 22 June 1593 between Ottoman Bosnian forces and a combined Christian army from the Habsburg lands, mainly Kingdom of Croatia and Inner Austria. The battle took place at Sisak, central Croatia, at the confluence of the Sava and Kupa rivers, on the borderland between Christian Europe and the Ottoman Empire.

Between 1591 and 1593 the Ottoman military governor of Bosnia, Beglerbeg Telli Hasan Pasha, attempted twice to capture the fortress of Sisak, one of the garrisoned castles that the Habsburgs maintained in Croatia as part of the Military Frontier. In 1592 after the key imperial fortress of Bihać fell to the Turks, only Sisak stood in the way before Croatia's main city Zagreb. Pope Clement VIII called for a Christian league against the Ottomans and the Sabor recruited in anticipation a force of about 5,000 professional soldiers.

On 15 June 1593, Sisak was once again besieged by the Bosnian Pasha and his Ghazi warriors. The Sisak garrison was commanded by Blaž Đurak and Matija Fintić, both Croatians from the Diocese of Zagreb. An Habsburg relief army under the supreme command of the Styrian general Ruprecht von Eggenberg, was quickly assembled to break the siege. The Croatian troops were led by the Ban of Croatia, Tamás Erdődy, while major forces from the Duchy of Carniola and the Duchy of Carinthia were under the commander of the Croatian Military Frontier Andreas von Auersperg, known as the "Carniolan Achilles".

On 22 June the Austro-Croatian relief army launched a surprise attack on the besieging forces, at the same time the garrison came out of the fortress to join the attack, the ensuing battle resulted in a crushing defeat for the Bosnian Ottoman army with Hasan Pacha killed and nearly all his army wiped out. The battle of Sisak is considered the main catalyst for the start of the Long War which raged between the Habsburgs and the Ottomans from 1593 to 1606.

Background[]

The central authorities of both the Ottoman Empire and the Habsburg Monarchy were rather reluctant to fight each other after several campaigns on Hungarian and Moldavian land and four renewals of the 1547 truce, but large scale raids were being mounted into each other's territories: There had been numerous raids into Habsburg Hungary by the akıncı, the irregular Ottoman light cavalry, and on the other hand, Uskoci (Balkan Habsburg-sided irregular soldiers on the eastern Adriatic coast) were being encouraged to conduct raids into Ottoman territory in the Balkans. Clashes on the Croatian frontier also continued despite the truce. The Croatian–Ottoman border went between Koprivnica and Virovitica to Sisak, then westward to Karlovac, southward to Plitvice Lakes, and southwest to the Adriatic Sea.[10] Croatia at the time had only 16,800 km² of free territory and around 400,000 inhabitants.[11]

Although its strength was depleted from the constant conflicts on the border, late in the 16th century Croatian fortified cities were able to hold Ottoman forces at bay.[12] During this period Ottoman Bosnian forces had made several attempts to seize major forts and towns across the Una and Sava rivers. On 26 October 1584 smaller Ottoman units were defeated at the battle of Slunj, and on 6 December 1586 near Ivanić-Grad.[6] However, Ottoman raids and attacks were increasing and the Croatian nobility were fighting without Habsburg support.[10]

The Uskok attack on the Sanjak of Krka was angered by the Ottoman people and officials in the region. Ibrahim, sanjak beg of the Krka, went to Istanbul to make talks with high level officials. He wanted compensation for the damage caused by Uskoks. Ottoman officials asked for an information on the issue from the Venetian ambassador to Istanbul. Because the Ottomans had a point of view that the Uskok raiders are subjected to the Republic of Venice. But Bailo of Constantinople rejected the accusations and said that the Uskoks are subjected to the Holy Roman Empire. Ibrahim requested that a letter be written to the German emperor for the damage caused by Uskoks in accordance with the ahidname. Ottoman grandvisier commissioned Telli Hasan Pasha, who is newly appointed at the Bosnian Eyalet, to make investigation on the issue. No letter has been found in the archives written to the Holy Roman Empire regarding Krka raid. Regardless of whether the letter is sent or not, it is clear that the Ottomans could not find anyone to make talks on the issue and soon they began to prepare for war to take revenge from the Uskok raiders and their supporters.[13]

Premise[]

In August 1591, without a declaration of war, Telli Hasan Pasha, Ottoman beylerbey of the Eyalet of Bosnia and vizier, attacked Croatia and reached Sisak, but was repelled after four days of fighting. Tamás Erdődy, Ban of Croatia, launched a counterattack and seized much of the Moslavina region. The same year Hasan Pasha launched another attack, taking the town of Ripač on the Una River. These raids forced Erdődy to convene a meeting of the Croatian Parliament in Zagreb on 5 January 1592 and declare a general uprising to defend the country.[6][14] These actions of the regional Ottoman forces under Hasan Pasha seem to have been contrary to the interest and policy of the central Ottoman administration in Constantinople,[15] and due rather to aims of conquest and organized plundering by the war-like Bosnian sipahi, although perhaps also under the pretext of putting an end to Uskok raids into the Eyalet, since the two realms had signed a nine-year peace treaty earlier in 1590.

In June 1592 Hasan Pasha captured Bihać and directed his forces towards Sisak for the second time. The fall of Bihać caused fear in Croatia since it had stood on the border for decades.[16] Hasan Pasha also successfully captured and burnt the Ban's military encampment in Brest on 19 July 1592, built by Erdődy a few months earlier near Petrinja. The camp had around 3,000 men, while the Ottoman forces had around 7–8,000. On 24 July the Ottomans started besieging Sisak, but lifted the siege after 5 days of fighting and heavy losses, leaving the region of Turopolje ravaged. These events encouraged the Emperor to make more effort in order to stop the Ottomans, whose actions were halted by the winter.[6][17]

Battle[]

In spring 1593, Beylerbey Telli Hasan Pasha gathered a large army in Petrinja and on 15 June again crossed the Kupa River and started his third attack on Sisak. His Bosnian Ottoman army[18] consisted of around 12,000-16,000 troops from the sanjaks of Klis, Lika, Zvornik, Herzegovina, Pojega, and Cernik. Sisak was defended by at most 800 men commanded by Matija Fintić, who died on 21 June, and Blaž Đurak, both from Kaptol, seat of the Roman Catholic bishop of Zagreb. The town was under heavy artillery fire and a call for help was sent to the Croatian ban. Reinforcements led by Austrian Colonel-General Ruprecht von Eggenberg, Ban Tamás Erdődy, and Colonel Andreas von Auersperg arrived near Sisak on 21 June. They numbered around 4,000–5,000 cavalry and infantry. Mustafa Naima narrates that, after making the preparations before the battle, Hasan Pasha commanded Gazi Hodža Memi Bey, father of Sarhoš Ibrahim Pasha, a renowned military commander, to cross the river and reconnoitre the enemy forces. He reported back that a battle would end in ruin, as the Habsburgs had such a superior force (probably referring to its larger quantity of guns and ammunition). Naima also narrates that after hearing this, Hasan Pasha, who was credited as a fearless military leader,[19] and happened to be playing chess at that very moment, severely responded to him: "Curse you, you despicable wretch! to be afraid of numbers: out of my sight!", and then he mounted his horse and began to mobilize the Ottoman forces across the bridges he had previously ordered to be constructed.[20]

Croatian Ban Tamás Erdődy set out to help the endangered town with 1,240 of his soldiers. He was joined by Andreas von Auersperg with 300 armourers from Kranjska and Carinthia, then German troops Ruprecht Eggenberg with 300 soldiers, Stjepan Grasswein, commander of the Slavonian Krajina and its 400 horsemen, Petar Erdődy with 500 Žumberak Uskoks, Melchior Rödern with 500 Tole archers, Adam Rauber of Weiner with 200 arcebuzirs, Krštofor Obrutschan with 100 men, Stjepan Tahy with 80 hussars, Martin Pietschnik from Altenhof with 100 guys, Georg Sigismund Paradeiser, commander of the Karlovac, Carinthian and Kranj Musketeers with 160 men, Ferdinand Weidner with 100 pedestrians and Count Montecuccoli with 100 horsemen.[21] In addition, the following Croatian captains were present with their armies: Ivan Draskovic, Benedict Thuroczy, Franjo Orehovački, Vuk od Druškovca and Count Stjepan Blagajski.[22] Thus, this Croatian-Slovenian-German army, which came to the aid of the besieged Croatian city, gathered about 5,000–6,000 battlers, with more than two-thirds of them being Croatians.

On 22 June, between eleven and twelve o'clock, Erdődy and Auersperg's forces attacked Ottoman positions with the army of Erdődy in front, consisting of Croatian hussars and infantry.[3][23] The first assault was repulsed by Ottoman cavalry. Then the soldiers of Colonel Auersperg joined the attack followed by Eggenberg's and other commanders' men, forcing the Ottomans back towards the Kupa River. The army of Hasan Pasha was driven into a corner between the rivers Odra and the Kupa, with the bridge across the Kupa taken by soldiers from Karlovac.[3][23] The Sisak garrison led by Blaž Đurak attacked the remaining Ottoman forces that were besieging Sisak. Caught in the middle between two Christian army flanks, the Ottomans panicked and started a chaotic retreat, trying to swim across the Kupa River and reach their camp. The bulk of the army, with most of the commanders, were either slaughtered or drowned in the river.[4]

The battle lasted around one hour and ended in a total defeat of the Ottomans. Predojević (Nikola Predojević is the original name of Telli Hasan Pasha) did not survive the battle. Among the Ottoman commanders that were killed or had drowned in Kupa were Sultanzade Mehmet Bey of the Sanjak of Herzegovina, Džafer Bey of the Sanjak of Pakrac-Cernica, as well as Hasan's brother, Arnaud Memi Bey of the Sanjak of Zvornik, and Ramazan Bey of the Sanjak of Pojega. Ibrahim Bey of the Sanjak of Lika managed to escape.[4] Total Ottoman losses were around 8,000 killed or drowned.[1] The Christian army captured 2,000 horses, 10 war flags, falconets, and artillery ammunition left by the Ottomans.[4][24] Christian army losses were light; a report from Andreas von Auersperg submitted to Archduke Ernest on 24 June 1593 mentions only 40–50 casualties for his troops.[25][7]

Aftermath and consequences[]

Christian Europe was delighted at the grandiose reports of the victory at Sisak. Pope Clement VIII praised the Christian military leaders, sending a letter of gratitude to Ban Erdődy, while King Philip II of Spain named Erdődy a knight of the Order of Saint Saviour. The Diocese of Zagreb built a chapel in the village of Greda near Sisak to commemorate the victory and the bishop decreed that a Mass of thanksgiving should be held every 22 June in Zagreb. The cloak of Hasan Pasha was given to the Ljubljana Cathedral.[26] Blaž Đurak, commander of the Sisak garrison, was awarded by the Croatian Parliament for his contribution to the victory.[27]

Ban Tamás Erdődy wanted to take advantage of the victory and take Petrinja, where the remnants of the Ottoman army fled. However, Colonel General Eggenberg considered that there was not enough food for their army and the attack on Petrinja was halted.[26] After news of the defeat reached Constantinople, revenge was demanded from the military leaders and the Sultan's sister, whose son Mehmed was killed in the battle. Although the action of Hasan Pasha was not in accordance with the interests and policy of the Porte, the Sultan felt that such an embarrassing defeat, even of a vassal acting on his own initiative, could not go unavenged. Sultan Murad III declared war on Emperor Rudolf II that same year, starting the Long War that was fought mainly in Hungary and Croatia.[6][15][28] The war extended through the reign of Mehmed III (1595–1603) and into that of Ahmed I (1603–1617).[29]

During the war the Ottomans managed to take Sisak. On 24 August 1593, the Ottomans used the absence of a large army near Sisak, which was defended by 100 soldiers. With strong cannon fire they managed to break through the walls and on 30 August the fortress surrendered. On 10 September 1593, Sisak captured by Ottomans in command of Rumeli Beglerbeg Mehmed Pasha.[30][page needed] On 11 August 1594, the Ottoman garrison fled and set the fortress on fire.[28] The Long War ended with the Peace of Zsitvatorok on 11 November 1606, marking the first sign of the suppression of Ottoman expansion into Central Europe and stabilization of the frontier for half a century.[31] Inner Austria with the duchies of Styria, Carinthia, and Carniola remained free from Ottoman control. Croatia was also able to maintain its independence from further Ottoman incursions and made some territorial gains following the peace treaty, such as Petrinja, Moslavina, and Čazma.[12][32] It is also important to point out that after this first great Ottoman defeat in northwestern Balkans, the Orthodox Christian subjects of the empire, particularly Serbs and Vlachs (who had been loyal and military useful) began then to lose faith in their Muslim masters, and began passing slowly over to the Habsburg side by emigrating from Ottoman-controlled lands to those of the Habsburgs, or even revolting against the Ottomans in their own territory (Uprising in Banat).[33]

Legacy[]

As the battle took place on Croatian territory and the main body of the Christian defenders consisted of Croatian troops, the victory has ever since played a major role in the historiography of Croatia. The Croatian government issued a commemorative stamp in 1993 called "Victory at Sisak".[34] The traditional daily ringing of the small bell of Zagreb Cathedral at 2 PM is in memory of the battle as it was the bishop of Zagreb who had borne the major part of the costs of the fortress of Sisak.[35]

Since fighters from neighbouring Carniola reinforced the defenders, the battle is also a part of the Slovenian tradition. On 22 June 1993, the Republic of Slovenia issued three memorial coins and a postage stamp to commemorate the 400 years anniversary of the battle of Sisak.[36][37] Until 1943, an annual commemoration service was held in the Catholic Church of Ljubljana, with the officiating priest wearing a cloak representing Hasan Pasha.[38]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Oto Luthar: The Land Between: A History of Slovenia (Peter Lang GmbH, 2008), p. 215

- ^ Jump up to: a b Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall, Geschichte des Osmanischen Reiches. Vol.4: Vom Regierungsantritte Murad des Dritten bis zur zweyten Entthronung Mustafa des Ersten 1574–1623, Budapest: C. A. Hartleben, 1829, p. 218 and footnote with reference to the greatly differing figures in Turkish sources, e.g. Mustafa Naima,Tarichi Naima (i.e. "Naima's History"), Constantinople 1734, vol.I, p. 43 f. (Annals of the Turkish Empire: from 1591 to 1659. Transl. Charles Fraser. London: Oriental Translation Fund, 1832), and Austrian sources, e.g. Franz Christoph von Khevenhüller (1588–1650), Annales Ferdinandei, Leipzig: Weidmann 1721–1726, vol. IV, p. 1093.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Ive Mažuran: Povijest Hrvatske od 15. stoljeća do 18. stoljeća, p. 146

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Vjekoslav Klaić: Povijest Hrvata od najstarijih vremena do svršetka XIX. stoljeća, Knjiga peta, Zagreb, 1988, p. 496

- ^ Ivo Goldstein: Sisačka bitka 1593., Zagreb, 1994, p. 104

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Ferdo Šišić: Povijest Hrvata; pregled povijesti hrvatskog naroda 600 – 1918, pp. 305–306, Zagreb ISBN 953-214-197-9

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Luthar, O. (2008). The Land Between: A History of Slovenia. Peter Lang. p. 215. ISBN 978-3-631-57011-1.

- ^ Bánlaky József: A magyar nemzet hadtörténelme; A sziszeki csata 1593 június 22.-én

- ^ (Croatian: Bitka kod Siska; Slovene: Bitka pri Sisku; German: Schlacht bei Sissek; Turkish: Kulpa Bozgunu)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gábor Ágoston, Bruce Alan Masters: Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire, Infobase Publishing, 2009, p. 164

- ^ Ivo Goldstein: Sisačka bitka 1593., Zagreb, 1994, p. 30

- ^ Jump up to: a b Alexander Mikaberidze: Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia, 2011, p. 188

- ^ Gulhan, Muhammet. "Yeni Belgelerin Işığında Telli Hasan Paşa'nın Osmanlı-Habsburg Sınırındaki Faaliyetleri (1591–1593)". Akademik Tarih ve Düşünce Dergisi (in Turkish). 7: 1263 – via Dergipark.

- ^ Vjekoslav Klaić: Povijest Hrvata od najstarijih vremena do svršetka XIX. stoljeća, Knjiga peta, Zagreb, 1988, p. 471

- ^ Jump up to: a b Moačanin, Nenad: Some Problems of Interpretation of Turkish Sources concerning the Battle of Sisak in 1593, in: Nazor, Ante et al (ed.), Sisačka bitka 1593 Archived 2011-07-16 at the Wayback Machine, Proceedings of the Meeting from 18–19 June 1993. Zagreb-Sisak (1994); pp. 125–130.

- ^ Vjekoslav Klaić: Povijest Hrvata od najstarijih vremena do svršetka XIX. stoljeća, Knjiga peta, Zagreb, 1988, p. 480

- ^ Vjekoslav Klaić: Povijest Hrvata od najstarijih vremena do svršetka XIX. stoljeća, Knjiga peta, Zagreb, 1988, pp. 483–486

- ^ Mikaberidze, A. (2011). Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia [2 volumes]: A Historical Encyclopedia. Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-337-8.

- ^ Hivzija Hasandedić (1990). Muslimanska baština u istočnoj Hercegovini (Muslim heritage in eastern Herzegovina). El-Kalem, Sarajevo. p. 168.

- ^ Mustafa Naima (1832). Annals of the Turkish Empire from 1591 to 1659 of the Christian Era. Oriental Translation Fund. pp. 14–15.

- ^ Aleksije Olesnički, Tko nosi odgovornost za poraz turske vojske kod Siska 20. ramazana 1001. godine (22. lipnja 1593)? // Vjesnik Arheološkog muzeja u Zagrebu, sv. 22–23, br. 1, (1942), pp. 115–173., p. 130

- ^ Mislav Barić, Dugi rat u Hrvatskoj: ratnici i ratništvo (Kriegswesen): diplomski rad, Filozofski fakultet Sveučilišta u Zagrebu, Zagreb, 2015, p. 69

- ^ Jump up to: a b Vjekoslav Klaić: Povijest Hrvata od najstarijih vremena do svršetka XIX. stoljeća, Knjiga peta, Zagreb, 1988, pp. 494–495

- ^ Radoslav Lopašić: Spomenici Hrvatske krajine: Od god. 1479–1610, Zagreb, 1884, p. 179-180

- ^ Radoslav Lopašić: Spomenici Hrvatske krajine: Od god. 1479–1610, Zagreb, 1884, p. 182-184; General Andrija Auersperg izvješćuje nadvojvodu Ernsta o porazu Turaka pod Siskom.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Vjekoslav Klaić: Povijest Hrvata od najstarijih vremena do svršetka XIX. stoljeća, Knjiga peta, Zagreb, 1988, p. 497

- ^ Ivo Goldstein: Sisačka bitka 1593., Zagreb, 1994, p. 73

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ive Mažuran: Povijest Hrvatske od 15. stoljeća do 18. stoljeća, p. 148

- ^ Stanford J. Shaw, History of the Ottoman empire and Modern Turkey. Vol. 1: Empire of Gazis, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976, p. 184; ISBN 0-521-29163-1.

- ^ Selânikî Mustafa Efendi. (1999). Tarih-i Selânikî. İpşirli, Mehmet. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu. ISBN 975-16-0893-7. OCLC 283479874.

- ^ Alexander Mikaberidze: Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia, 2011, p. 152-153

- ^ Trpimir Macan: Povijest hrvatskog naroda, 1971, p. 207

- ^ Ferdo Šišić: Povijest Hrvata; pregled povijesti hrvatskog naroda 600 – 1918, p. 345, Zagreb ISBN 953-214-197-9

- ^ "HRVATSKE POVIJESNE BITKE – POBJEDA KOD SISKA".

- ^ Bruno Sušanj, Zagreb – Tourist Guide, Zagreb: Masmedia Nikola Štambak, 2006, p. 22

- ^ "400 years anniversary of the battle at Sisak", bsi.si (1993); accessed 22 June 2014.

- ^ Pošta Slovenije: 1993 Stamps – 400th anniversary of the Battle of Sisak, 22 June 1993; accessed 22 June 2014.

- ^ Copland, Fanny S. (1949). "The Battle of Sisek". The Slavonic and East European Review. 27: 339–344.

Literature[]

- Stanford J. Shaw (1976), History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey: Vol. 1: Empire of Gazis, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ISBN 0-521-29163-1.

- Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall, Geschichte des Osmanischen Reiches Großentheils aus bisher unbenützten Handschriften und Archiven. Vol.4: Vom Regierungsantritte Murad des Dritten bis zur zweyten Entthronung Mustafa des Ersten 1574–1623, Budapest: C. A. Hartleben, 1829. Reprint: Graz: Akademische Druck-u. Verlagsanstalt, 1963.

- Alfred H. Loebl, Das Reitergefecht bei Sissek vom 22. Juni 1593. Mitteilungen des Instituts für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung IX (1915), pp. 767–787.(German)

- Peter Radics, Die Schlacht bei Sissek, 22. Juni 1593, Ljubljana: Josef Blasnik, 1861 (German)

- Fanny S. Copland (translation from 18th century Slovene), The Slavonic and East European Review, vol. 27, no. 69, 1949, pp. 339–344, "The Battle of Sisek."

- Sisak

- Battles involving Habsburg Croatia

- 1590s in Croatia

- 1593 in Europe

- Battles involving the Ottoman Empire

- Battles involving the Holy Roman Empire

- Conflicts in 1593

- 1593 in the Ottoman Empire

- 16th century military history of Croatia

- Battles of the Long Turkish War

- Hundred Years' Croatian–Ottoman War

- History of Banovina

- Battles involving Ottoman Bosnia and Herzegovina