Bernardino de Escalante

Bernardino de Escalante (ca. 1537[1]– after 1605) was a Spanish soldier, priest, geographer and a prolific writer. He is best known as the author of the second book on China that was published in Europe, and the first author of such a book to obtain wide circulation outside of Portugal.[2]

The foremost scholar of the European literature about Asia, Donald F. Lach, noted in 1965 about Escalante, "Very little is known about his biography".[2] However, a significant amount of research on Escalante, spearheaded by Rufo de Francisco, was carried out in the late 20th century.[3]

Biography[]

Bernardino de Escalante was born in Laredo, Cantabria, and came from a lineage of Cantabrian hidalgos. His father, García de Escalante, was a sea captain and shipowner. Based in Laredo, then one of the most important ports of Spain's northern coast, García de Escalante engaged in sea trade and participated in a number of important military campaigns.[5] Some of Bernardino's early training was as part of the crew of his father's boat, on its twice-a-year journeys to Flanders.[4]

Bernardino's mother, Francisca de Hoyo, belonged to a well-connected family as well: her sister Catalina de Hoyo was married to Prince Philip's (later, King Philip II's) secretary, Pedro del Hoyo.[5]

Following his uncle Pedro, young Bernardino de Escalante entered the retinue of the future King Philip II in 1554.[5] He was aboard his father's boat, La Concepción, which was part of the fleet taking Prince Philip to England for his wedding with Mary I of England. The knowledge of Britain which he acquired during his 14 months' stay there shows in his later writing.[4]

In 1555-1558, Bernardino de Escalante participated in the war in Flanders, and fought at St. Quentin. It is not known whether he returned to Spain in 1559 (during which year his father died, the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis was signed, and Philip II returned to Spain), or stayed in Flanders until the end of the mop-up operations in January 1561.[6]

Soon after returning to Spain, Escalante felt that the period of European wars was over, and he also deserved a peaceful life, perhaps as a scholar or ecclesiastic. He went to study, although which university he attended is unknown.[7]

It is known that in the 1570s he enjoyed a benefice at a Laredo church, and served as the commissar of the Spanish Inquisition for the Kingdom of Galicia, often making business trips to Lisbon and Sevilla.[7][8] At some point he was apparently transferred to Sevilla, then Spain's main port for the America trade; in 1581, he was an inquisitor in that city, and was also the majordomo of the Archbishop of Seville, Rodrigo de Castro Osorio.[7]

Spanish archives contain memorials written by Escalante for Philip II, his ministers and top archbishops, dated between 1585 and 1605. They discuss a variety of geopolitical issues, in particular related to the uneasy Anglo-Spanish relations, and, according to the 20th-century historian J.L. Casado Soto (who published these documents in 1995), were studied by "Philip the Prudent" and his officials.[9]

[]

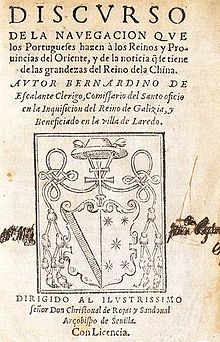

Of particular historical interest is Escalante's first published book, Discurso de la navegacion que los Portugueses hacen a los Reinos y Provincias de Oriente, y de la noticia que se tiene de las grandezas del Reino de la China (Discourse of the navigation made by the Portuguese to the kingdoms and provinces of the Orient, and of the existing knowledge of the greatness of the Kingdom of China). Published in Sevilla in 1577, it became, according to Donald F. Lach, the second European book primarily dedicated to China, after Gaspar da Cruz' Tratado das cousas da China (1569).[2]

Content of the Discurso and its sources[]

Escalante Discurso was a fairly small book, 100 folios (i.e., 200 pages in the modern system of page-counting) in octavo with wide margins. It can be conceptually divided into two parts. The first 5 chapters (folios 1-28) cover the history of Portuguese explorations along the route from the Iberian Peninsula to the South-East Asia. The remaining chapters (chap. 6-16, on folios 28-99) attempt a systematic description of China - its geography, economy, culture etc., to the (rather limited) extent known at the time to the Europeans (primarily Portuguese). The last folio (100) contains a brief description of the author's sources.

Escalante is not known to have traveled to China. As he explains on the last page of his Discurso, his work is primarily that of synthesis. His literary sources were primarily Portuguese, viz. the above mentioned 1569 book by the Dominican Gaspar de Cruz (who had preached in Guangzhou for a month), and the coverage of China in the 3rd Década of the Décadas da Ásia by João de Barros (the 3rd Década was published in 1563; Barros never went to Asia either, but in his Lisbon office had access to Chinese books and a literate Chinese slave who was able to read and interpret them for him.[2][10]). Escalante had also been interviewing Portuguese merchants who had traveled to the China coast, and even some "people of China" who had come to Spain ("los mesmos naturales Chinas que an venido à España").[2]

Influence of the book[]

Unlike da Cruz's treatise, which apparently remained fairly obscure outside of Portugal, Escalante's book was quickly translated to other European languages. The English translation, by John Frampton, appeared in 1579, under the title A discourse of the Navigation which the Portugales doe Make to the Realmes and Provinces of the East Partes of the Worlde, and of the knowledge that growes by them of the great thinges, which are in the Dominion of China.[11]

Escalante's Discurso was one of the main sources[12] for a much bigger book: Juan González de Mendoza's (1585), which became Europe's standard reference on China for several decades.[2]

Chinese language and characters in the Discurso[]

Chapter XI of the Discurso discusses Chinese writing system, as well as education in China. While Escalante's description of the Chinese writing is generally similar to that given by da Cruz (absence of a phonetic alphabet; around 5000 different characters, each representing not just a syllable, but a particular meaning; usefulness of the written languages for communication between people who speak mutually incomprehensible languages of China, or even languages of other nearby countries such as Japan, Ryukyu, and Vietnam; writing in vertical columns), there are also significant differences. While da Cruz gives a first-hand account of the "purser" of a Chinese boat explaining to him the essentials of the writing system (after he had finished writing a note to the Vietnamese port authorities), Escalante gives an abstract textbook-type description. da Cruz gives the correct pronunciation (tiem) of one character (the one with the meaning "heaven" - i.e., obviously, 天, whose modern Pinyin transcription is tian), but does not actually show the characters. Escalante's book shows 3 sample characters, even if quite deformed and hardly recognizable, while his phonetic values are harder to interpret.[13]

Escalante's sample of characters is not the earliest known example of hanzi/kanji printed in a European book: the earliest published examples known to researchers appeared in a collection of Jesuit letters from Asia printed in Portugal in 1570; however, those were drawn from a Japanese, rather than Chinese, context.[14][15]

Escalante's sample became quite influential, primarily via the two publications that reproduced his discussion of the Chinese writing systems (including his characters):

- Abraham Ortelius's atlas Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (1584 edition), where these examples appeared in the brief text accompanying Luis Jorgé de Barbuda's map of China,[15][16]

- Mendoza's Historia ... de la China (1585), whose chapter on Chinese writing is based on Escalante.[17]

As the characters given by Escalante (and faithfully reproduced by Barbuda and Mendoza) are quite deformed, there has been a fair amount of discussion among commentators and translators of their works as to what their original form was.

- The first character, said to mean "heaven" and have the sound value Guant, is, according to the 1853 Hakluyt Society commentators, George Staunton and R.H. Major, hard to interpret. They make a guess that it might be [6]