Bluff War

| Bluff War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Ute Wars, Navajo Wars | |||||||

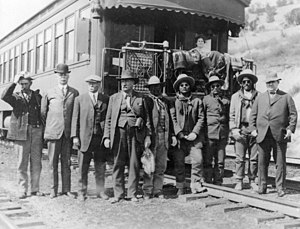

Prisoners of the Bluff War in Thompson, Utah, waiting to board a train for their trial in Salt Lake City. Photo includes Marshal Nebeker, carrying the binoculars, and General Scott, third from left. Chief Polk is standing in between Nebeker and Jess Posey, while Chief Posey stands to the right of Jess, next to Tse-ne-gat. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Ute Paiute | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Polk Posey | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

~2 killed ~5 wounded |

1 killed 2 wounded ~160 captured | ||||||

| Civilian Casualties 2 killed | |||||||

The Bluff War, also known as Posey War of 1915, or the Polk and Posse War, was one of the last armed conflicts between the United States and native Americans. It began in March 1914 and was the result of an incident between a Utah shepherd and Tse-ne-gat, the son of the Paiute Chief Narraguinnep ("Polk"). It was notable for involving Chief Posey and his band of renegades who helped Polk fight a small guerrilla war against local Mormon settlers and Navajo policemen. The conflict centered on the town of Bluff, Utah and ended in March 1915 when Polk and Posey surrendered to the United States Army.[1][2][3]

War[]

Ute Mountain Incident[]

Chief Posey played a prominent role in the war, as it was primarily his band who took up arms. Between 1881 and 1923, Posey led his braves in several skirmishes against the Navajo and the American settlers, killing several, including several at the "Pinhook Massacre" on the northwest slopes of the La Sal Mountains. His band, which included about 100 people, both Ute and Paiute, was feared and well-known. Unlike most native American tribes, Polk's and Posey's followers did not reside on a reservation, but rather they lived near Bluff, around Allen and Montezuma Canyons. Ultimately, Posey's struggle to keep Westward expansion away failed in 1905, when the town of Blanding, then known as Grayson, was founded in the center of the Ute's last prominent hunting grounds. For the next ten years, sporadic fighting occurred, until March 1914 when Tse-ne-gat, the son of Chief Polk, allegedly robbed and murdered an ethnic Mexican shepherd named Juan Chacon on the Ute Mountain Reservation in Colorado. Chacon had camped with a group of Utes and Paiutes from Polk's band, among them Tse-ne-gat, also known as Everett Hatch. A few days later Chacon was found dead and witnesses claimed that Tse-ne-gat was responsible. Chief Polk defended his son's actions, so when Navajo policemen attempted to arrest Tse-ne-gat, Polk drove them off with rifle fire. For the next six months, newspapers around the United States circulated reports of the incident. By that time, Polk had taken his band, about eighty-five people, to the Navajo Mountain area. Chief Posey and his warriors joined them, setting the stage for a battle. Local newspapers reported that "Hatch [Tse-ne-gat] has a notorious reputation as a bad man" and that his group was "terrorizing" the settlers in the Bluff area, they also said that Tsa-na-gat was "strongly entrenched with fifty braves who will stand by him to the last man."[4][5][6]

Battle of Cottonwood Gulch[]

Ten months after the murder of Chacon, Tsa-na-gat still had not surrendered so Marshal Aquila Nebeker organized a posse of twenty-six "cowboys" and three sheriffs from Montezuma County, Colorado to make arrests. The posse left Bluff and headed towards Navajo Mountain. Just after dawn, on the morning of February 25, 1915, Marshal Nebeker and the posse came across Chief Polk and fifty of his men encamped in Cottonwood Gulch. The weather was very cold and snow covered the ground. One of the natives in camp spotted the approaching possemen, so he alarmed the others with "woops of warning" before opening fire with a rifle. Other accounts say that the posse achieved a surprise attack and began firing into the camp without warning. Either way, the posse implemented a type of "Indian strategy of the kind that one is accustomed to read in the histories of early life in the West." Chief Posey and his band were camped not far from the area, along the San Juan River, and when they heard the sound of the gunfire, Posey led his warriors to Polk's rescue. Posey's men, numbering about forty, maneuvered to the rear of the posse's position and then he gave the order to engage. Shortly thereafter, Marshal Nebeker realized that he needed help, so he sent a message back to Bluff requesting reinforcements. Over the next several hours, about fifty volunteers from Bluff, Blanding, Cortez and Monticello arrived in the battle area. The fight continued all night and into the next day, when a truce was called. During the fighting, five of the possemen got separated from the rest and had to hold off the attacking natives from the top of a rocky hill. At least one American was killed, posseman Joseph C. Akin of Colorado, and several others were wounded,[7][8] though some accounts say two possemen died.[9][10][11]

One native, known only as "Jack's Brother" was killed and two others received wounds. A second native woman was also killed when she "ran into the line of battle." Two of the natives, named Howen and Jack, were captured by the posse and later described by The Day as being "choice warriors." When the truce was called, Nebeker retreated to Bluff while Chief Polk and Posey led their bands further into the desert. It was believed that after defeating the posse, the two renegade bands would besiege Bluff, but this did not happen. According to newspapers, there were enough men in Bluff to defend the town, but not enough to pursue the natives if and when they chose to escape. Sometime later, a force of about fifty Navajo policemen, from the Navajo Reservation, caught up with the hostiles, but were repulsed in the following skirmish. After that, the handling of the situation was turned over to Brigadier General Hugh L. Scott.[12][13][14]

Surrender at Mexican Hat[]

Upon receiving orders, General Scott traveled all the way from his post in Virginia City to Bluff, in order to negotiate an end to the war. Scott was genuinely uninterested in fighting the hostile Utes and Paiutes, so on March 10, 1915 he left Bluff, unarmed, with just a few of his men, to meet Polk and Posey at a place called Mexican Hat, near Navajo Mountain. General Scott described the journey; "We reached Bluff on March 10 and learned that the Indians had gone to the Navajo Mountains, 125 miles southwest of Bluff. We stayed a day in Bluff and then went on to Mexican Hat. Some friendly Navajos met me at Mexican Hat and went ahead of me to tell Poke's [Chief Polk] band of my coming. Among them was Bzoshe, the old Navajo chief with whom the government had so much trouble with a year ago and who is now our fast friend. I had sent for him to meet me at Bluff. Mr. Jenkins, Indian agent at Navajo Springs, Mr. Creel, Colonel Michie, and my orderly accompanied me to Mexican Hat. None of us had a gun. Jim Boy, a friendly Paiute, was sent out to tell the Paiutes that I wanted to see them. Some of them came near where I was camped, but it wasn't until the third day that anyone dared to come to the camp. Posey and four other Indians then came in. We talked a little through a Navajo interpreter. It was in the evening, and I just asked them how they were. I told them I did not feel very well and did not want to talk to them until the next day. They helped us kill a beef and we gave them a good meal, the first they'd had in weeks. We also gave them some blankets. Posey and his men didn't have any weapons, but I have reason to suspect that they had hidden them nearby. The next day, Poke and Hatch [Tse-ne-gat] and about 25 others came to see me. I asked them to tell me their troubles. I said that I didn't think they would like to have their children chased by soldiers and cowboys all over the mountains and killed and that I wanted to help them. I didn't try to push the matter with them, but asked them what they wanted to do. After they had talked among themselves, they said they would do anything I wanted them to do."[15]

Polk and Posey agreed to surrender Tse-ne-gat, so the three of them, as well as Posey's son Jess, were put into army custody to await trial. The four men were jailed in Salt Lake City, but Polk, Posey and Jess were released soon after. Tse-ne-gat was not released and he was sent to Denver to face charges for the murder of Juan Chacon in 1914. In Denver, the trial concluded that Tse-ne-gat would be freed, mainly because there was no evidence against him and partly because of a protest by the Indian Rights Association and a pair of Mormons in Bluff, who said the boy was innocent. Tse-ne-gat was said to have been extremely happy after the verdict, and he spent the remainder of his time in Denver staying at the finest hotels and dining at quality restaurants. The court's decision was of little consolation to Polk's and Posey's bands. Between the beginning and end of the war, about 160 natives were captured and sent to live on the Ute Mountain Reservation. It wasn't until about 1920 that the natives began resettling in Allen and Montezuma Canyons.[16][17]

See also[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bluff War. |

References[]

- ^ http://historytogo.utah.gov/people/ethnic_cultures/the_history_of_utahs_american_indians/chapter6.html

- ^ "J. Willard Marriott Digital Library".

- ^ http://www.sanjuan.k12.ut.us/sjsample/POSEY/WEBDOC13.HTM#1915 Archived 2012-04-23 at the Wayback Machine Indian War

- ^ "San Juan School District".

- ^ http://historytogo.utah.gov/people/ethnic_cultures/the_history_of_utahs_american_indians/chapter6.html

- ^ "San Juan School District".

- ^ The North Platte semi-weekly tribune., February 26, 1915, Image 2 Col 5

- ^ The Ogden Standard Feb 22, 1915 reports posseman Jose Cardova wounded

- ^ "The Day - Google News Archive Search".

- ^ "Posey".

- ^ http://historytogo.utah.gov/people/ethnic_cultures/the_history_of_utahs_american_indians/chapter6.html

- ^ Roberts, pg. 162

- ^ "EAU Claire Leader Newspaper Archives, Feb 23, 1915, p. 1". 23 February 1915.

- ^ "The Day - Google News Archive Search".

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-04-23. Retrieved 2011-10-22.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Young, pg. 62

- ^ http://historytogo.utah.gov/people/ethnic_cultures/the_history_of_utahs_american_indians/chapter6.html

Bibliography[]

- Young, Richard K. (1997). The Ute Indians of Colorado in the twentieth century. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2968-9.

- Roberts, David (2008). Living With Wolves. Braided River. ISBN 978-1-59485-004-2.

- Wars fought in Utah

- History of Colorado

- 20th-century military history of the United States

- Wars involving the United States

- Wars involving the indigenous peoples of North America

- 1915 in the United States

- Ute people

- Paiute people

- Navajo history

- Mormonism and Native Americans