British Museum Reading Room

| British Museum Reading Room | |

|---|---|

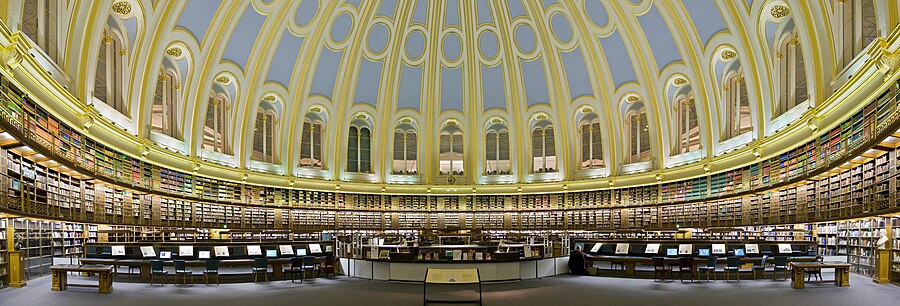

Inside the Reading Room, before its conversion to an exhibition space | |

| |

| General information | |

| Town or city | Bloomsbury, London |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 51°31′10″N 00°07′37″W / 51.51944°N 0.12694°WCoordinates: 51°31′10″N 00°07′37″W / 51.51944°N 0.12694°W |

| Construction started | 1854 |

| Completed | 1857 |

| Technical details | |

| Structural system | Segmented domed |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Sydney Smirke |

The British Museum Reading Room, situated in the centre of the Great Court of the British Museum, used to be the main reading room of the British Library. In 1997, this function moved to the new British Library building at St Pancras, London, but the Reading Room remains in its original form at the British Museum.

Designed by Sydney Smirke and opened in 1857, the Reading Room was in continual use until its temporary closure for renovation in 1997. It was reopened in 2000, and from 2007 to 2017 it was used to stage temporary exhibitions. It has since been closed while its future use remains under discussion.

History[]

Construction and design[]

In the early 1850s the museum library was in need of a larger reading room and the then-Keeper of Printed Books, Antonio Panizzi, following an earlier competition idea by William Hosking, came up with the thought of a round room in the central courtyard. The building was designed by Sydney Smirke and was constructed between 1854 and 1857. The building used cast iron, concrete, glass and the latest technology in ventilation and heating. The dome, inspired by the Pantheon in Rome, has a diameter of 42.6 metres but is not technically free standing: constructed in segments on cast iron, the ceiling is suspended and made out of papier-mâché. Book stacks built around the reading room were made of iron to take the huge weight and add fire protection. There were forty kilometres of shelving in the stacks prior to the library's relocation to the new site.[1]

The British Museum Library[]

The Reading Room was officially opened on 2 May 1857 with a 'breakfast' (that included champagne and ice cream) laid out on the catalogue desks. A public viewing was held between 8 and 16 May, attracting over 62,000 visitors. Tickets to it included a plan of the library.[1][2]

Regular users had to apply in writing and be issued a reader's ticket by the Principal Librarian.[1] During the period of the British Library, access was restricted to registered researchers only; however, reader's credentials were generally available to anyone who could show that they were a serious researcher. The Reading Room was used by a large number of famous figures, including notably Sun Yat-sen, Karl Marx, Oscar Wilde, Friedrich Hayek, Marcus Garvey, Bram Stoker, Mahatma Gandhi, Rudyard Kipling, George Orwell, George Bernard Shaw, Mark Twain, Vladimir Lenin (using the name Jacob Richter[1]), Virginia Woolf, Arthur Rimbaud, Mohammad Ali Jinnah,[3] H. G. Wells[4] and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.[1]

In 1973, the British Library Act 1972 detached the library department from the British Museum, but it continued to host the now separated British Library in the same Reading Room and building as the museum until 1997.

Closure and restoration[]

In 1997 the British Library moved to its own specially constructed building next to St Pancras Station and all the books and shelving were removed. As part of the redevelopment of the Great Court, the Reading Room was fully renovated and restored, including the papier-mâché ceiling which was repaired to its original colour scheme, having previously undergone radical redecorations (the initial design of the roof was considered excessive at the time).[1][5]

The Reading Room was reopened in 2000, allowing all visitors, and not just library ticket-holders, to enter it. It held a collection of 25,000 books focusing on the cultures represented in the museum along with an information centre and the Walter and Leonore Annenberg Centre.[1]

Exhibition space[]

In 2007 the books and facilities installed in 2000 were removed, and the Reading Room was relaunched as a venue for special exhibitions, beginning with one featuring China's Terracotta Army. The general library for visitors (Paul Hamlyn Library) moved to a room accessible through nearby Room 2, but closed permanently on 13 August 2011. This is an earlier library that has also had distinguished users, including Thomas Babington Macaulay, William Makepeace Thackeray, Robert Browning, Giuseppe Mazzini, Charles Darwin and Charles Dickens.[6]

A selection of past exhibitions:[7]

| Exhibit | From | To |

|---|---|---|

| The First Emperor: China's Terracotta Army[8] | 13 September 2007 | 6 April 2008 |

| Hadrian: Empire and Conflict[9][10] | 24 July 2008 | 27 October 2008 |

| Shah ʿAbbas: The Remaking of Iran[7] | 19 February 2009 | 14 June 2009 |

| Indian Summer[7] | May 2009 | September 2009 |

| Montezuma: Aztec Ruler[7] | 24 September 2009 | 24 January 2010 |

| Italian Renaissance drawings[11] | 22 April 2010 | 25 July 2010 |

| Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead: Journey Through the Afterlife[12] | 4 November 2010 | 6 March 2011 |

| Treasures of Heaven: Saints, Relics and Devotion in Medieval Europe[13] | 23 June 2011 | 9 October 2011 |

| Hajj: journey to the heart of Islam | 26 January 2012 | 15 April 2012 |

| Shakespeare: staging the world | 19 July 2012 | 25 November 2012 |

| Life and death in Pompeii and Herculaneum | 28 March 2013 | 29 September 2013 |

| Vikings: life and legend[7] | 6 March 2014 | 22 June 2014 |

| Ancient lives, new discoveries[7] | 22 May 2014 | 12 July 2015 |

| Germany: memories of a nation[7] | 16 October 2014 | 25 January 2015 |

| Indigenous Australia: enduring civilisations[7] | 23 April 2015 | 2 August 2015 |

| Drawing in silver and gold: Leonardo to Jasper Johns[7] | 10 September 2015 | 6 December 2015 |

| Celts: art and identity[7] | 24 September 2015 | 31 January 2016 |

| Egypt: faith after the pharaohs[7] | 29 October 2015 | 7 February 2016 |

| Sunken Cities: Egypt's lost worlds[7] | 19 May 2016 | 27 November 2016 |

| Hokusai: beyond the Great Wave[7] | 25 May 2017 | 13 August 2017 |

References in art and popular culture[]

This section does not cite any sources. (January 2019) |

The British Museum Reading Room is the subject of an eponymous poem, "The British Museum Reading Room", by Louis MacNeice. Much of the action of David Lodge's 1965 novel The British Museum Is Falling Down takes place in the old Reading Room. The 'Glass Ceiling' of Anabel Donald's 1994 novel is the ceiling of the Reading Room, where the denouement is set.

Alfred Hitchcock used the Reading Room and the dome of the British Museum as a location for the climax of his first sound film Blackmail (1929). Other movies with key scenes in the Reading Room include Night of the Demon (1957) and in the 2001 Japanese anime OVA Read or Die, the Room is used as a secret entrance to the British Library's fictional "Special Operations Division".

In Sir Max Beerbohm's short story, Enoch Soames, first published in May 1916, an obscure writer makes a deal with the Devil to visit the Reading Room one hundred years in the future, in order to know what posterity thinks about him and his work.

The British Museum and the Reading Room serve as the settings for An Encounter at the Museum, an anthology of romance novellas by Claudia Dain and Deb Marlowe, among others.

Virginia Woolf made reference to the British Museum Reading Room in a passage from her 1929 essay, A Room of One's Own. She wrote, "The swing doors swung open, and there one stood under the vast dome as if one were a thought in the huge bald forehead which is so splendidly encircled by a band of famous names."[14]

Richard Henry Dana, Jr. visited the Reading Room on 10 September 1860 with his London friend Henry T. Parker, and reported that

Parker calls & takes me to the British Museum, to see the Reading Room, wh. has been built since 1856 [Dana's prior visit]. It is the room where students & readers have their desks, & consult the textbooks, cyclopedias, catalogs &c., & from wh. they send orders for books to the Library – the Library not being visited, at all, for study. There is no such room as this in Europe. It is a circle, with a dome, lighted from above, & its diameter is 4 feet greater than that of the dome of St. Paul's. The autographs are now open to the view of all, spread out in glass cases, – as well as much other lit. curiosities. This is the grandest Literary & Scientific institution (not for instruction) in the world. The Reading Room, I told Parker, was a temple to the deification of Bibliology.[15]

The writer Bernard Falk (1882-1960) quotes the British historian Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881) as having declared that the Reading Room of the British Museum was a convenient asylum for imbeciles whose friends wished them out of mischief's way.[16]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "Reading Room". The British Museum. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Invitation to a private view of the Round Reading Room, British Museum

- ^ Wolpert, Stanley Jinnah of Pakistan, p. 13

- ^ Charles Godfrey-Faussett (1 May 2004), Footprint England, Footprint Travel Guides, p. 884, ISBN 978-1-903471-91-3, ISBN 1903471915

- ^ "BBC News | Entertainment | Facelift for British Museum's reading room". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ "BM confirms closure of Paul Hamlyn library | Museums Association". www.museumsassociation.org. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m "British Museum - Past exhibitions". 9 February 2018. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ "British Museum - The First Emperor: China's Terracotta Army". 1 April 2019. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ "British Museum - Archive: Hadrian". 23 March 2019. Archived from the original on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ "Hadrian: Empire and Conflict, British Museum, London". the Guardian. 19 July 2008. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ "British Museum - Archive: Fra Angelico to Leonardo: Italian Renaissance Drawings". 12 October 2018. Archived from the original on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ "British Museum - Book of the Dead". 28 October 2018. Archived from the original on 28 October 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ "British Museum - Treasures of Heaven". 5 September 2019. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Hoberman, Ruth (Fall 2002). "Women in the British Reading Room During the Late-Nineteenth and Early-Twentieth Centuries: From Quasi- to Counterpublic". Feminist Studies. 28 (3): 489–512. doi:10.2307/3178782.

- ^ Richard H. Dana, Jr., Journal of a Voyage Round the World 1859–1860, Library of America Ed. pp. 861–62 (2005)

- ^ Falk, Bernard (1951) Bouquets for Fleet Street, London, Hutchinson & Co, p.157

Further reading[]

- A History of the British Museum Library, 1753–1973. London: British Library, 1998, ISBN 0-7123-4562-0, ISBN 978-0-7123-4562-0

- Caygill, M. The British Museum Reading Room. London: The British Museum, 2000. ISBN 0-86159-985-3

- Wilson, David M. The British Museum; A History. London: The British Museum Press, 2002, ISBN 0-7141-2764-7

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to British Museum Reading Room. |

- 1857 establishments in the United Kingdom

- British Library

- British Museum

- Domes

- Grade I listed library buildings

- Buildings and structures completed in 1857

- Buildings and structures in Bloomsbury