Buada Lagoon

| Buada Lagoon | |

|---|---|

Buada Lagoon | |

Buada Lagoon | |

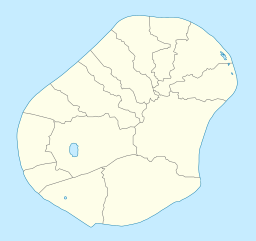

| Location | Nauru |

| Coordinates | 0°32′7″S 166°55′20″E / 0.53528°S 166.92222°ECoordinates: 0°32′7″S 166°55′20″E / 0.53528°S 166.92222°E |

| Type | lake |

| Surface area | 0.05 square miles (0.13 km2) |

Buada Lagoon is a landlocked, slightly brackish, freshwater lake of Buada District in the island nation of Nauru. It occupies about 0.05 square miles (0.13 km2).

The lagoon is classified as an endorheic lake, meaning there is no outflow to other bodies of water such as oceans or rivers.

The Buada Lagoon is the biggest and only true lake in Nauru, a small independent republic in Oceania consisting of a flat island of 21.3 km² in area. The lake lies in Nauru's Buada district, from which it gets its name. It is not a lagoon as such, in that the lake is not joined to the sea, but its water is slightly brackish.[1][2]

Freshwater is rare in Nauru, being present only in the form of a small phreatic zone, the Moqua Well (a small underground lake) and the Buada Lagoon, which is the most visible, rivers and streams being utterly absent from the country.[3][4]

The lake has traditionally been used for pisciculture, which saw the raising of milkfish for human consumption through the centuries, and even though this practice was given up in the 1960s, it has lately seen efforts to revive it, despite the lagoon's water pollution.

Geography[]

Geology and hydrology[]

The Buada Lagoon, which is found in the southwest of the plateau that spreads over most of the central part of the island of Nauru, lies in the middle of a swampy depression of 12 hectares.[5]

This karstic bowl,[4] dominated in the northwest by Command Ridge, the island's highest point, came about as a result of sagging of the ground, itself arising from dissolving coral limestone, the mineral that makes up a great part of the plateau's rocks in the form of pinnacles, among which phosphate ore, of a high level of purity, is found.[6] The lagoon's basin, though, is the only region of the plateau where the ore, which was the mainstay of Nauru's economy through the 20th century, was never exploited.[6]

Oval in shape, with a length of roughly 280 m along a north-south axis and a width of about 140 m, and lying some 1,300 m from the seashore, the Buada Lagoon is shallow, with a depth of one or two metres on average, reaching five metres at its deepest,[5] and its average surface level is near sea level.[5][1] However, the lake’s levels can vary considerable as a result of the Buada Lagoon's endoreic state; it has no outlet and is fed only by rainwater, there being no rivers at all in Nauru.[1] Thus, between the monsoon season from November to February, when most of the rain falls (this is on average some 2,126 mm each year[5][7]) and the dry season, especially in years when La Niña is present,[4] the low-water level can sink as far down as five metres below sea level.[5][1]

The lake’s greenish waters are slightly brackish, with a salt concentration of 2‰,[2][1] and slightly basic with a pH of 8.[1]

Flora[]

Very little information is available about the Buada Lagoon's lacustrine flora,[7][1] even though the presence of water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) was confirmed not long ago.[8]

The vegetation along the lake's edge to a great extent represents a relic of the tropical forest that occupied 90% of the island before the phosphate ore began to be exploited in the 20th century.[8] Covering 40 hectares and growing on a fertile, waterlogged soil,[4] it is made up mostly of tamanu (Calophyllum inophyllum) along with a few Rubiaceae like Guettarda speciosa, and also Premna serratifolia, sea almond, Adenanthera pavonina, kapok, Mimosa pudica, mango, sea mango, coconut, while the undergrowth is mainly made up of Scaevola (notably Scaevola taccada), noni, hopbush, Physalis angulata, ferns like monarch fern and giant swordfern, and parasitic plants like Cassytha filiformis, or Psilotum nudum.[8] is found in open areas while Cyperus (specifically Cyperus javanicus and Cyperus compressus, species close to papyrus), Portulaca oleracea and Ipomoea aquatica are found in the wetlands, much of which was destroyed during the Japanese Occupation during the Second World War.[8] Further, exotic plants such as guava, lantana, Grona triflora and Chamaesyce hirta have colonized places that have experienced disturbances.[8]

Within this forest, on small parcels of land, are grown fruit trees such as pandan, breadfruit, banana, mango, guava and soursop, as well as vegetables such as cabbage and bitter melon for consumption.[1][9] Also grown are ylang-ylang, Cassia grandis, Crotalaria spectabilis, Samanea saman, seagrape and, for ornamentation, some Asteraceae such as Ageratum conyzoides and Synedrella nodiflora.[8]

Fauna[]

Insects[]

The lagoon's depression is one place on Nauru where insects proliferate, mostly because of the nearby expanses of stagnant freshwater such as the Buada Lagoon itself and also the rainwater cisterns found at dwellings and farms.[9][10]

Thus, three species of mosquito, Culex quinquefasciatus, Culex sitiens and Aedes aegypti, proliferate in the monsoon season from November to February near expanses of stagnant freshwater like household rainwater cisterns, used tires, wells and, of course, the Buada Lagoon, albeit only slightly more seriously than towards the seashore.[10] These mosquitos, beyond simply being an annoyance to the local populace at dawn, also carry a parasitic illness, filariasis, although the incidence among the local people is not high.[10] The only two predators that feed on these mosquitos are fishes, the milkfish and the gambusia, which feed themselves on the larvae as well as two species of Odonata.[10]

Three species of fruit flies, the oriental fruit fly, the Pacific fruit fly and the mango fly, were present before the 2000s and caused considerable damage to farms.[9] The lands around the Buada Lagoon have been affected by these flies, who have found a breeding ground in the many fruit trees grown there. The flies have also been the object of eradication efforts, some of which have met with success, such as the one against the oriental fruit fly, which was eliminated in 1999.[11][12]

Birds[]

Birds, particularly seabirds, are Nauru's most visible animals, and some stop there in great numbers during their migration or for nesting.[5]

Only one bird species, the Nauru reed warbler, is endemic, but it is threatened with extinction by habitat destruction, even though it has been colonizing areas recently reforested now that phosphate deposits are no longer being exploited on the island's plateau.[13] This species likes shrubby areas in the tropical rainforest, farms and gardens, including the area around the Buada Lagoon, which are associated with those three habitats.[13]

Fishes[]

Three fish species are found in the Buada Lagoon: milkfish, Mozambique tilapia and gambusia,[1][10] those last two having been introduced to Nauru, the tilapia to afford the local people a new food source, and the gambusia to help eradicate mosquitos.[14]

In certain years, Nauruans traditionally practised pisciculture by catching milkfish in the island's inshore waters (by some definitions, the actual lagoon, just behind the offshore coral reefs) and releasing them into the Buada Lagoon and another such body of water at Anabar.[12][1] Indeed, the fish thus raised have long been considered a high-quality food by the Nauruans for being so rich in fat.[12] Fish farming therefore stood as a social organizer between different tribes: the exploitation was shared by tribes by using low walls, looking after the fish was trusted to men who regularly waded in the waters to keep them oxygenated and filled with nutrients, and children were forbidden to bother the fish when they bathed in the waters.[12]

About 1960, Mozambique tilapias were introduced into the Buada Lagoon in the hopes of getting pisciculture going again and limiting the invasion of mosquitos.[12][1][7] Unfortunately, the tilapias multiplied to such an extent that they presented some serious competition to the milkfish being raised in the lagoon,[1] with no milkfish ever reaching a size suitable for harvest, that being some 20 cm long. This led many fish farmers to give up the trade, as the tilapias themselves were not very good to eat.[12]

To set this ecological blunder right, a number of attempts were made, some meeting with no success, and others even worsening an already bad situation. So the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), at Nauru's request, put in place a programme to reduce the tilapia population between 1979 and 1980.[7][1] This programme entailed spreading rotenone on the lake's surface; this is a highly toxic molecule, particularly to fish, and dangerous to humans, but also biodegradable. The lake was thus temporarily poisoned.[1]

In 1991, the FAO's "South Pacific Aquaculture Development Project" (SPADP) showed that it was possible that the milkfish and the tilapia could coexist in fish farming.[12] The FAO thus introduced in 1998 Nile tilapias into the Buada Lagoon, an experiment much like one carried out in Fiji that had shown them to have qualities that better appealed to local people's tastes. This meant that pisciculture might be revived in Nauru.[12] At the same time, a Taiwanese project also sought to revive fish farming by using intensive methods of raising fish, but these were nevertheless both given up for want of funds.[12]

The failure of these attempts to get the fish farming industry running again then led to the establishment of a semi-intensive aquaculture programme, also Taiwanese, in 2001 which involved building concrete basins 20 m long, 10 m wide and 1.5 m deep. These were equipped with oxygenators, nets and specially adapted feeding.[12] The idea was to allow fish farmers to raise milkfish using seawater, and without having to share the water with tilapias.[12]

Human presence[]

Buada Lagoon, Nauru's only inhabited inland area, with some 660 inhabitants living around it,[4] lies in the centre-west of Buada District. Girded by a road, the lakeshore is made up of private residential properties[1] where fruit trees are grown, such as pandan, breadfruit, banana, mango, guava and soursop, and along with those such vegetables as cabbage and bitter melon.[1][9] These households together form the community of Arenibek.

Since the island's sewage treatment and household waste collection are not very efficient, the lake becomes polluted with both sewage and rubbish from the shore residents,[1][15] which leads to contamination from Escherichia coli.[16] Despite these threats of environmental degradation, no protective measures are being undertaken, even though Buada Lagoon would seem to meet the criteria of the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance.[7]

See also[]

- Endorheic lake

- Geography of Nauru

- Moqua Well

- Pisciculture

- Buada District

- Districts of Nauru

- Early history of Nauru

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Protected Areas and World Heritage Programme - Buada Lagoon.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wetlands International - A Directory of Wetlands in Oceania Archived 2011-08-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Climate Change Response Under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification - First National Report for Nauru.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f , ed. (30 July 2008). "National Assessment Report" (pdf). .

- ^ Jump up to: a b Carl N. McDaniel, John M. Gowdy, Paradise for Sale, Chapitre 2 Archived 2007-10-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Protected Areas and World Heritage Programme - Nauru". Archived from the original on 2002-11-11. Retrieved 2021-03-06.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f University of Hawaii at Manoa - Atoll Research Bulletin n° 392 Archived 2007-03-02 at the Wayback Machine The Flora of Nauru

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Eradication of introduced Bactrocera species in Nauru using male annihilation and protein bait application techniques Archived 2006-09-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Organisation mondiale de la santé - A survey of Nauru island for mosquitoes and their internal pathogens and parasite Archived 2007-09-26 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ (in French) Service de la protection des végétaux - Secrétariat général de la Communauté du Pacifique.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k Secretary of the Pacific Community - Bactrocera dorsalis.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Acrocephalus rehsei (Finsch, 1883) at the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species

- ^ Australian Dictionnary of Biography - Chalmers, Frederick Royden (1881 - 1943).

- ^ The way ahead: an assessment of waste problems for the Buada community, and strategies toward community waste reduction in Nauru Problèmes de santé à Nauru, en particulier à la lagune Buada.

- ^ Secretariat of the Pacific Community - Newsletter n°111 d'octobre et décembre 2004.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Buada Lagoon. |

- First National Report To the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) URL Accessed 2006-05-03 – Drinking water problem in Nauru

- Secretariat of the Pacific Community - Nauru Fisheries and Marine Resources Authority Aquaculture development programme in Nauru

External links[]

![]() Media related to Buada Lagoon at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Buada Lagoon at Wikimedia Commons

- Lakes of Nauru

- Endorheic lakes of Oceania