Calcium hydroxide

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Calcium hydroxide

| |

Other names

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.013.762 |

| EC Number |

|

| E number | E526 (acidity regulators, ...) |

| 846915 | |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| Properties | |

| Ca(OH)2 | |

| Molar mass | 74.093 g/mol |

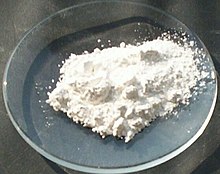

| Appearance | White powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 2.211 g/cm3, solid |

| Melting point | 580 °C (1,076 °F; 853 K) (loses water, decomposes) |

| |

Solubility product (Ksp)

|

5.5×10−6 [citation needed] decreasing with T |

| Solubility | |

| Basicity (pKb) | 1.37 (first OH−), 2.43 (second OH−)[1][2] [clarification needed] |

| −22.0·10−6 cm3/mol | |

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.574 |

| Structure | |

| Hexagonal, hP3[3] | |

| P3m1 No. 164 | |

a = 0.35853 nm, c = 0.4895 nm

| |

| Thermochemistry | |

Std molar

entropy (S |

83 J·mol−1·K−1[4] |

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−987 kJ·mol−1[4] |

| Hazards | |

| Safety data sheet | See: data page [5] |

| GHS pictograms |

|

| GHS Signal word | Danger |

GHS hazard statements

|

H314, H318, H335, H402 |

| P261, P280, P305+351+338 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

3

0

0 |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose)

|

7340 mg/kg (oral, rat) 7300 mg/kg (mouse) |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible)

|

TWA 15 mg/m3 (total) 5 mg/m3 (resp.)[6] |

REL (Recommended)

|

TWA 5 mg/m3[6] |

IDLH (Immediate danger)

|

N.D.[6] |

| Related compounds | |

Other cations

|

Magnesium hydroxide Strontium hydroxide Barium hydroxide |

Related bases

|

Calcium oxide |

| Supplementary data page | |

Structure and

properties |

Refractive index (n), Dielectric constant (εr), etc. |

Thermodynamic

data |

Phase behaviour solid–liquid–gas |

Spectral data

|

UV, IR, NMR, MS |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Calcium hydroxide (traditionally called slaked lime) is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula Ca(OH)2. It is a colorless crystal or white powder and is produced when quicklime (calcium oxide) is mixed or slaked with water. It has many names including hydrated lime, caustic lime, builders' lime, slack lime, cal, and pickling lime. Calcium hydroxide is used in many applications, including food preparation, where it has been identified as E number E526. Limewater is the common name for a saturated solution of calcium hydroxide.

Properties[]

Calcium hydroxide is poorly soluble in water with a retrograde solubility increasing from 0.66 g/L at 100 °C to 1.89 g/L at 0 °C. With a solubility product Ksp of 5.5×10−6 at T = ?[clarification needed].[citation needed] its dissociation in water is large enough that its solutions are basic according to the following dissolution reaction:

- Ca(OH)2 → Ca2+ + 2 OH−

At ambient temperature, calcium hydroxide (portlandite) dissolves in pure water to produce an alkaline solution with a pH of about 12.5. Calcium hydroxide solutions can cause chemical burns. At high pH value due to a common-ion effect with the hydroxide anion OH−

, its solubility drastically decreases. This behavior is relevant to cement pastes. Aqueous solutions of calcium hydroxide are called limewater and are medium-strength bases, which reacts with acids and can attack some metals such as aluminium (amphoteric hydroxide dissolving at high pH), while protecting other metals, such as iron and steel, from corrosion by passivation of their surface. Limewater turns milky in the presence of carbon dioxide due to formation of calcium carbonate, a process called carbonatation:

- Ca(OH)2 + CO2 → CaCO3 + H2O

When heated to 512 °C, the partial pressure of water in equilibrium with calcium hydroxide reaches 101 kPa (normal atmospheric pressure), which decomposes calcium hydroxide into calcium oxide and water:[7]

- Ca(OH)2 → CaO + H2O

Structure, preparation, occurrence[]

Calcium hydroxide adopts a polymeric structure, as do all metal hydroxides. The structure is identical to that of Mg(OH)2 (brucite structure); i.e., the cadmium iodide motif. Strong hydrogen bonds exist between the layers.[8]

Calcium hydroxide is produced commercially by treating lime with water:

- CaO + H2O → Ca(OH)2

In the laboratory it can be prepared by mixing aqueous solutions of calcium chloride and sodium hydroxide. The mineral form, portlandite, is relatively rare but can be found in some volcanic, plutonic, and metamorphic rocks. It has also been known to arise in burning coal dumps.

The positively charged ionized species CaOH+ has been detected in the atmosphere of S-type stars.[9]

Retrograde solubility[]

The solubility of calcium hydroxide at 70 °C is about half of its value at 25 °C. According to Hopkins and Wulff (1965),[10] the decrease of calcium hydroxide solubility with temperature is known since a long time by the works of Marcellin Berthelot (1875)[11] and Julius Thomsen (1883)[12] (see Thomsen–Berthelot principle), when the presence of ions in aqueous solutions was still questioned. Since, it has been studied in detail by many authors, a.o., Miller and Witt (1929)[13] or Johnston and Grove (1931)[14] and refined many times (e.g., Greenberg and Copeland (1960);[15] Hopkins and Wulff (1965);[10] Seewald and Seyfried (1991);[16] Duchesne and Reardon (1995)[17]).

The reason for this rather uncommon behavior is that the dissolution of calcium hydroxide in water is an exothermic process. Thus, according to Le Chatelier's principle, a lowering of temperature favours the elimination of the heat liberated through the process of dissolution and increases the equilibrium constant of dissolution of Ca(OH)2, and so increase its solubility at low temperature. This counter-intuitive temperature dependence of the solubility is referred to as "retrograde" or "inverse" solubility. The variably hydrated phases of calcium sulfate (gypsum, bassanite and anhydrite) also exhibit a retrograde solubility for the same reason because their dissolution reactions are exothermic.

Uses[]

Calcium hydroxide is commonly used to prepare lime mortar.

One significant application of calcium hydroxide is as a flocculant, in water and sewage treatment. It forms a fluffy charged solid that aids in the removal of smaller particles from water, resulting in a clearer product. This application is enabled by the low cost and low toxicity of calcium hydroxide. It is also used in fresh-water treatment for raising the pH of the water so that pipes will not corrode where the base water is acidic, because it is self-regulating and does not raise the pH too much.

It is also used in the preparation of ammonia gas (NH3), using the following reaction:

Another large application is in the paper industry, where it is an intermediate in the reaction in the production of sodium hydroxide. This conversion is part of the causticizing step in the Kraft process for making pulp.[8] In the causticizing operation, burned lime is added to green liquor, which is a solution primarily of sodium carbonate and sodium sulfate produced by dissolving smelt, which is the molten form of these chemicals from the recovery furnace.

Food industry[]

Because of its low toxicity and the mildness of its basic properties, slaked lime is widely used in the food industry:

- In USDA certified food production in plants and livestock[18]

- To clarify raw juice from sugarcane or sugar beets in the sugar industry, (see carbonatation)

- To process water for alcoholic beverages and soft drinks

- Pickle cucumbers and other foods

- To make Chinese century eggs

- In maize preparation: removes the cellulose hull of maize kernels (see nixtamalization)

- To clear a brine of carbonates of calcium and magnesium in the manufacture of salt for food and pharmaceutical uses

- In fortifying (Ca supplement) fruit drinks, such as orange juice, and infant formula

- As a digestive aid (called Choona, used in India in paan, a mixture of areca nuts, calcium hydroxide and a variety of seeds wrapped in betel leaves)

- As a substitute for baking soda in making papadam

- In the removal of carbon dioxide from controlled atmosphere produce storage rooms

- In the preparation of mushroom growing substrates[19]

Native American uses[]

In Spanish, calcium hydroxide is called cal. Maize cooked with cal (in a process of nixtamalization) becomes hominy (nixtamal), which significantly increases the bioavailability of niacin (vitamin B3), and is also considered tastier and easier to digest.

In chewing coca leaves, calcium hydroxide is usually chewed alongside to keep the alkaloid stimulants chemically available for absorption by the body. Similarly, Native Americans traditionally chewed tobacco leaves with calcium hydroxide derived from burnt mollusc shells to enhance the effects. It has also been used by some indigenous American tribes as an ingredient in yopo, a psychedelic snuff prepared from the beans of some Anadenanthera species.[20]

Asian uses[]

Calcium hydroxide is typically added to a bundle of areca nut and betel leaf called "paan" to keep the alkaloid stimulants chemically available to enter the bloodstream via sublingual absorption.

It is used in making naswar (also known as nass or niswar), a type of dipping tobacco made from fresh tobacco leaves, calcium hydroxide (chuna or soon), and wood ash. It is consumed most in the Pathan diaspora, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India and Bangladesh. Villagers also use calcium hydroxide to paint their mud houses in Afghanistan, Pakistan and India.

Health risks[]

Unprotected exposure to Ca(OH)2 can cause severe skin irritation, chemical burns, blindness, lung damage or rashes.[5]

See also[]

- Baralyme (carbon dioxide absorbent)

- Cement

- Lime mortar

- Lime plaster

- Plaster

- Magnesium hydroxide (less alkaline due to a lower solubility product)

- Soda lime (carbon dioxide absorbent)

- Whitewash

References[]

- ^ "Sortierte Liste: pKb-Werte, nach Ordnungszahl sortiert. – Das Periodensystem online".

- ^ ChemBuddy dissociation constants pKa and pKb

- ^ Petch, H. E. (1961). "The hydrogen positions in portlandite, Ca(OH)2, as indicated by the electron distribution". Acta Crystallographica. 14 (9): 950–957. doi:10.1107/S0365110X61002771.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Zumdahl, Steven S. (2009). Chemical Principles 6th Ed. Houghton Mifflin Company. p. A21. ISBN 978-0-618-94690-7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "MSDS Calcium hydroxide" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0092". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ Halstead, P. E.; Moore, A. E. (1957). "The Thermal Dissociation of Calcium Hydroxide". Journal of the Chemical Society. 769: 3873. doi:10.1039/JR9570003873.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Greenwood, N. N.; & Earnshaw, A. (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd Edn.), Oxford:Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-7506-3365-4.

- ^ Jørgensen, Uffe G. (1997), "Cool Star Models", in van Dishoeck, Ewine F. (ed.), Molecules in Astrophysics: Probes and Processes, International Astronomical Union Symposia. Molecules in Astrophysics: Probes and Processes, 178, Springer Science & Business Media, p. 446, ISBN 079234538X.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hopkins, Harry P.; Wulff, Claus A. (1965). "The solution thermochemistry of polyvalent electrolytes. I. Calcium hydroxide". The Journal of Physical Chemistry. 69 (1): 6–8. doi:10.1021/j100885a002. ISSN 0022-3654.

- ^ Berthelot, M. (1875). Dissolution des acides et des alcalis. [Dissolution of acids and alkalis]. In: Annales de Chimie et de Physique. Vol. 4, pp. 445–536.

- ^ Thomsen J. (1883). Thermochemische untersuchungen [Thermochemical studies]. Vol. III, Johann Ambrosius Barth Verlag, Leipzig.

- ^ Miller, L. B.; Witt, J. C. (1929). "Solubility of calcium hydroxide". The Journal of Physical Chemistry. 33 (2): 285–289. doi:10.1021/j150296a010. ISSN 0092-7325.

- ^ Johnston, John.; Grove, Clinton. (1931). "The solubility of calcium hydroxide in aqueous salt solutions". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 53 (11): 3976–3991. doi:10.1021/ja01362a009. ISSN 0002-7863.

- ^ Greenberg, S. A.; Copeland, L. E. (1960). "The thermodynamic functions for the solution of calcium hydroxide in water". The Journal of Physical Chemistry. 64 (8): 1057–1059. doi:10.1021/j100837a023. ISSN 0022-3654.

- ^ Seewald, Jeffrey S.; Seyfried, William E. (1991). "Experimental determination of portlandite solubility in H2O and acetate solutions at 100–350 °C and 500 bars: Constraints on calcium hydroxide and calcium acetate complex stability". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 55 (3): 659–669. doi:10.1016/0016-7037(91)90331-X. ISSN 0016-7037.

- ^ Duchesne, J.; Reardon, E.J. (1995). "Measurement and prediction of portlandite solubility in alkali solutions". Cement and Concrete Research. 25 (5): 1043–1053. doi:10.1016/0008-8846(95)00099-X. ISSN 0008-8846.

- ^ Pesticide Research Institute for the USDA National Organic Program (23 March 2015). "Hydrated Lime: Technical Evaluation Report" (PDF). Agriculture Marketing Services. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- ^ "Preparation of Mushroom Growing Substrates". North American Mycological Association. North American Mycological Association. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ de Smet, Peter A. G. M. (1985). "A multidisciplinary overview of intoxicating snuff rituals in the Western Hemisphere". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 3 (1): 3–49. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(85)90060-1. PMID 3887041.

External links[]

- National Lime Association. "Properties of typical commercial lime products. Solubility of calcium hydroxide in water" (PDF). lime.org. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- National Organic Standards Board Technical Advisory Panel (4 April 2002). "NOSB TAP Review: Calcium Hydroxide" (PDF). Organic Materials Review Institute. Archived from the original (.PDF) on 31 October 2007. Retrieved 5 February 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - CDC – NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards – Calcium Hydroxide

- MSDS Data Sheet

- Building materials

- Calcium compounds

- Dental materials

- Hydroxides

- Inorganic compounds

- Intoxication

- E-number additives