Canbury

| Canbury | |

|---|---|

Canbury Gardens and the River Thames | |

Canbury Location within Greater London | |

| Population | 12,373 (2011 Census. Ward)[1] |

| OS grid reference | TQ185705 |

| London borough | |

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | KINGSTON UPON THAMES |

| Postcode district | KT2 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | Metropolitan |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| UK Parliament | |

| London Assembly | |

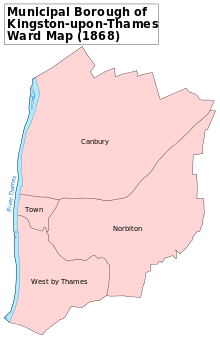

Canbury is a district of the northern part of Kingston upon Thames that takes its name from the historic manor that covered the area. Modern Canbury comprises two electoral wards in the constituency of Richmond Park; Canbury Ward to the south and Tudor Ward to the north.

History[]

There is evidence of prehistoric occupation from at least the Mesolithic along the river margins at Kingston, although most of the evidence tends to consist of scattered residual artefacts.[2] Despite numerous archaeological investigations in the area of Kingston since the 1960s there have been few in-situ archaeological finds and features dating to the Roman period. The few finds in Kingston come from Canbury; a burial ground excavated in the 19th century, not far from the river and railway line, excavations at Skerne Road in 2005, and the Sopwith Way and Skerne Road areas in 2007. These have revealed evidence of small-scale and agricultural Roman settlements.[2][3][4]

Manor[]

Despite Kingston's Saxon heritage, Canbury does not feature as part of the settlement of that period. Canbury, or Canonbury, is not mentioned in Domesday Book of 1086, but was held by Merton Priory at an early period, probably dating from the grant of Kingston Church by High Sheriff of Surrey Gilbert the Norman (or "Gilbert the Knight"), in about 1114.[5][6][7]

The possessions of the Merton monastery in Kingston and Hache, (Hatch), exclusive of Berwell,[where?] were valued, in Cardinal Beaufort's time, (c. 1374–1447) at 52s.[6] The manorial holdings included parts of open fields and buildings in the neighbouring manor of Ham with Hatch, probably the result of gifts to the church and priory as Ham had no church of its own until 1832 and lay within the parish of Kingston.[5] After the Dissolution of the Monasteries the manor, with the rectory and advowson of Kingston, was the subject of various Crown leases.[8]

The manor was bought for £4,000 by Sir John Ramsay in 1618. Ramsay also held land in Petersham and Ham to the north, living at Ham House. Ramsay was created Baron of Kingston upon Thames and Earl of Holderness in 1620, and obtained a grant of the advowson in 1622. He married Martha, daughter of Sir William Cockayne, and died without issue in 1626. The rectory, manor, and advowson then passed, under a settlement, to his widow, who married as her second husband Montague, Lord Willoughby. On the death of the Countess of Holderness without heirs in 1640, the advowson, rectory, and manor reverted to the Crown estate of King James I.[6][7] The Court-rolls show that in 1635 it became the property of William Murray, Esq. afterwards 1st Earl of Dysart, who had also acquired the lease of Ham House in 1626 following Ramsay's death.[6][9] In 1641 Murray conveyed the manor to Thomas Bruce, 1st Earl of Elgin, a relative of his wife.[8]

In 1652 it appears to have belonged to Arabella, Countess of Kent, and others. In 1664, it was the property of another John Ramsey, Esq. who alienated it to Nicholas Hardinge, Esq. in 1671. It continued in the Hardinge family for a century, becoming the property of George Hardinge Esq. M.P.. The manor included part of the town of Kingston.[6] John Rocque's map of 1746 shows the area comprising a patchwork of large fields transected by a few roads, the principle north–south route being Canbury Lane, the precursor to a section of the modern A307 road.[10]

Until this time it probably represented the early endowment of the church, and the manor had followed the descent of the advowson until 1786, when George Hardinge sold the right of patronage, but retained the manor.[7] The manor-house, which was close to the town, was sold to John Eddington, Esq.[6]

The manor house, Down Hall or Downhall, stood south of the railway line and bridge. It was described in 1911 as being a grey stuccoed house with jalousies and older kitchens behind. It had been held in the 13th century of the manor of Canbury (q.v.) by Lewin and , and was afterwards leased to and Beatrice his wife. In 1485–6 it was styled a 'capital messuage' or 'manor,' and was held of Merton by Robert Skerne, on whose death in that year it passed to Swithin his son. Robert Skerne was son of William Skerne, who founded the chantry in Kingston Church. William was nephew to Robert Skerne, who died in 1437, and has a brass in the church. Bray says, in his History of the County of Surrey that this Robert was also of Downhall, but others have been unable to corroborate this.[7] It was conveyed in 1617 by Mildred Bond, widow, and Thomas Bond to Anthony Browne and Matilda his wife. Not far away stood the ancient tithe barn, large enough for twelve teams to unload and with four threshing floors.[11] It was sold in 1850 and pulled down.[7]

The manor seems to have disappeared by the beginning of the 19th century following its sale on 4 September 1800 to Wilbraham Tollemache, 6th Earl of Dysart, whose family had retained the manors of Ham and Petersham to the north since their forebear, William Murray, had last held Canbury.[7]

Urbanisation[]

The Dysarts' acquisition of Canbury was well timed as Kingston expanded northwards during the 19th century. The expansion was driven by the coming of the railway to the area with the extension of the line from Twickenham to Kingston completed in 1863, then extended to Norbiton in 1869 to its terminus at Ludgate Hill. Developers bought 103 acres (42 ha) of Lord Liverpool's Farm to the north and east of the railway as well as 33 acres (13 ha) next to Kingston Station, and 44 acres (18 ha) of pasture and arable land of the Dysart estate. The mixed Victorian housing stock that characterises the area today reflects the piecemeal development that occurred during this period.[12]

Industrial development[]

The arrival of the railway also drove industrial growth. The poor sanitation of the expanding town was addressed, in part, by 1877 with the construction of sewage works near the river to the north of the railway line, operated on behalf of Kingston Corporation by the . Raw sewage was treated using the , toasted in huge ovens to produce a garden fertiliser sold as 'Native Guano'. King's Passage, at the end of the adjacent Canbury Gardens, was known at the time as 'Perfume Parade'. The public nuisance contributed to the decommissioning of the works in 1909.[13][14][15] A large part of the adjacent area was used for Kingston Gasworks, from the 1850s onwards. Although much of the site has since been redeveloped for retail, leisure, parking and residential use, the gasometers, the last remaining feature of the area, have now been demolished for the Queenshurst development.[13][16][17]

The coal-fired Kingston Power Station was built in 1894 with coal arriving by barge and rail and ash departing by barge. The station was closed in 1980, demolished, and the area, controversially, redeveloped for high-rise riverside apartments. The felling of a line of trees that had previously helped screen the power station from the river also aroused much local protest.[13]

The Sopwith Aviation Company expanded from its early beginnings at Brooklands to a former Roller Skating Rink in Canbury Park Road in 1912, drawing on the availability of boatbuilding and coachbuilding skills in the area to scale up aircraft production.[18][19] By 1915 they were successful enough to build a 5.5 acres (2.2 ha) site further along Canbury Park Road. The company rose to prominence during World War I producing many famous fighter aircraft including the Sopwith Camel and leasing National Aircraft Factory No 2 at Ham. After the war the Ham lease was sold and the company wound up but almost immediately reformed as H.G. Hawker Engineering at the Canbury Park Road site. The company and its successors remained there, going on to design and build the Hawker Hurricane fighter of World War II amongst many others. Hawker Aircraft bought the Ham factory in 1948 and, after redevelopment, moved from Canbury Park Road in 1958.[20] Both sites have since been redeveloped for residential use.

Open spaces[]

Some areas of open space were retained within the urban development. The riverside walk developed into Canbury Gardens. The nearby Richmond Road ground was an athletics and rugby ground before becoming the home of Kingstonian F.C. between 1919 and 1988. The Latchmere Recreation Ground was conveyed by William John Manners Tollemache, 9th Earl of Dysart and the Dysart Trustees on 23 February 1904 to the Municipal Borough of Kingston-upon-Thames, "Kingston Corporation", as part of the settlement of the Richmond, Petersham and Ham Open Spaces Act 1902. The land itself, though, remained within and defined part of the southern boundary of Ham Urban District.[21][22] This, and the southern half of Ham, was absorbed into Kingston, becoming part of the present day Tudor Ward when the Urban District was abolished in 1933.[23]

Geography[]

Canbury district extends westwards from the River Thames at Kingston Railway Bridge following the railway line through Kingston station eastwards towards Norbiton railway station and thence north to Richmond Park. It then extends northwards along the park wall to the border with the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames at Ham.

The Canbury electoral ward comprises four polling areas in the southern part of the district with a further four in Tudor Ward to the north.[24][25]

Canbury lies on alluvial flood plains extending from the river to the foot of Kingston Hill between 5.5m and 9.5m AOD and comprising river gravels overlain by holocene brickearth clays and silts.[3] The Latchmere Stream, a small watercourse now mostly culverted, that flows south–north along the foot of the hill towards Ham, once marked part of the boundary.[5] There is evidence that the area close to present day Kingston town centre was once crossed by many watercourses linking with the Thames and the Hogsmill forming a series of islands upon which Kingston was built, and the Latchmere linked with these.[4]

References[]

- ^ "Kingston Ward population 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- ^ a b Bradley, Timothy (2005). "Roman occupation at Skerne Road, Kingston upon Thames" (PDF). Surrey Archaeological Collections (92): 171–185.

- ^ a b Hawkins, Duncan (February 2006). "An Archaeological Assessment of Central Kingston" (PDF). Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 September 2012. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^ a b Hawkins, Duncan; Green, Christopher (2007). "A product of its environment: revising Roman Kingston" (PDF). London Archaeologist. 11 (8): 199–203.

- ^ a b c Cloake, John (2006). "The Robin Hood Lands, the Hamlet of Hatch and the Manor of Kingston Canbury". Journal of Richmond Local History Society. Richmond Local History Society (27): 74–76.

- ^ a b c d e f Lysons, Daniel (1792). "Kingston upon Thames". The Environs of London. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Malden, H E, ed. (1911). Kingston-upon-Thames: Manors, churches and charities. A History of the County of Surrey. Vol. 3. Institute of Historical Research. pp. 506, 512.

- ^ a b "Estates of the Tollemache Family of Ham House in Kingston upon Thames, Ham, Petersham and elsewhere: Records, 14th cent-1945". Surrey History Centre. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- ^ Pritchard, Evelyn (2007). Ham House and its owners through five centuries 1610–2006. London: Richmond Local History Society. pp. 1–4. ISBN 9781955071727.

- ^ An Exact Survey of the Citys of London, Westminster, ye Borough of Southwark, and the Country near Ten Miles round (Map) (1769 print ed.). 5 1/2 in. : 1 Stat. Mile (1 : 11520). Cartography by John Rocque. London: British Library.

- ^ Pennant, Thomas; Wallis, John (1814). London: Being a Complete Guide to the British Capital: Containing a Full and Accurate Account of Its Buildings, Commerce, Curiosities ... Including a Sketch of the Surrounding Country, with Full Directions to Strangers on Their First Arrival (4 ed.). Sherwood, Neely, and Jones.

- ^ Canbury, Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames, 2009

- ^ a b c "Landscape Character Reach 5. Hampton Wick". Thames Landscape Strategy. p. 233.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Guano Seal, Native Guano Company". Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- ^ "The Sewage Problem Solved". The New Zealand Herald. 19 September 1889. p. 6.

- ^ Logan, Ross (5 July 2013). "Iconic Gasworks site could be demolished". Kingston Guardian.

- ^ "Queenshurst | Stylish Apartments in Kingston".

- ^ "Sopwith Aviation – The Founding Fathers" (PDF). Kingston Aviation. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ^ "1913". Kingston Aviation. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ^ "Sopwith Aviation and Hawker Aircraft at Canbury Park Road, Kingston" (PDF). Kingston Aviation. 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ^ Surrey VI.SE (includes: Ham; Kingston upon Thames; Twickenham St Mary the Virgin.) (Map) (Revised: 1911 to 1912 ed.). 1:10,560. Ordnance Survey Maps - Six-inch England and Wales, 1842-1952. National Library of Scotland. 1920.

- ^ "History". Friends of Latchmere Recreation Ground. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ Great Britain Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth, Ham Urban District. Retrieved 2009-10-29.

- ^ Canbury Ward Map (PDF) (Map). Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 August 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ^ Tudor Ward Map (PDF) (Map). Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 August 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- Areas of London

- Districts of the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames