Casea

| Casea | |

|---|---|

| |

| C. broilii skeleton in the Field Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | †Caseasauria |

| Family: | †Caseidae |

| Genus: | †Casea Williston, 1910 |

| Type species | |

| Casea broilii Williston, 1910

| |

| Other species | |

| |

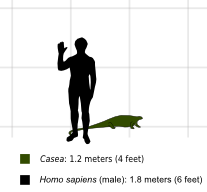

Casea is an extinct genus of medium to large-bodied, herbivorous, pelycosaur synapsids from the late Carboniferous until the middle Permian. The name Casea references its appearance from the Caseasauria which developed new morphology of their external naris and snout. Casea were known to be about 1.2 meters (4 ft) long.[1] It weighed between 150 kg to 200 kg. It was slightly smaller than the otherwise very similar Caseoides. Casea was one of the first amniote herbivores, sharing its world with animals such as Dimetrodon and Eryops. It was possibly also aquatic.[2]

Casea is primarily known from fossil localities in North America, mainly in Texas. However, from high latitudes in the fore region of Russia and Aveyron, France more fossil sites have been located. With this greater extension of fossil, it is possible those fossil lineages express a longer lifespan of the Casea species.[3] In the development of its proportionally thick, stout limbs it represents the culmination of the Casea lineage.[2]

Description[]

Casea belong to the group of six families at the very base of the synapsid lineage known as pelycosauria. Pelycosaurs are a paraphyletic evolutionary grade thought to share ancestry with mammals by the mainstream scientific community.[4] Casea were herbivores and fairly large animals. Their size could be an indication of an advantage that size would give in warding off the attacks of carnivores.[5]

Skull[]

The skull of Casea had a larger orbit and was relatively wide, with the bone being pitted and the teeth long and blunt. Their common features are enumerated by Olson and include a very short snout, proportionally very small skulls, a barrel shaped body and a reduced phalangeal formula. [6] The structure of the skull has no lower temporal arcade, along with many other characters of the skeleton that justifies a suborbital position. These specimens show a loose union of the squamosal with the quadrate.[3] The skull is anteriorly broad and posteriorly short relative to its length and is shallow dorsoventrally. The skull roof is deeper in the posterior portions because of a slight doming of the parietal bones and the angled ventral cheek margin.[6]

The posterior margin of the skull is slightly inclined anterodorsally, and the occipital bone follows this inclination, projecting slightly beyond the posterior margin of the skull. In dorsal view the outline of the skull roof is spade shaped with the cheek region wider than the skull table. The palate is broad and plate-like. Casea genus has a narrow interpterygoid vacuity that divides the posterior portions of the palate at the midline.[6] The jaw is dominated by a large dentary and a strong medially directed process off the articular bone is present at the level of the articular facets for the quadrate.[6]

Post-cranial skeleton[]

Post cranial development includes the characters of the skeleton are larger part of a tail, the sacrum, two lumbar vertebrae, pelvis, and the complete hind legs. The ribs of the sacral vertebrae decrease in mediolateral length posteriorly so that the sacrum tapers posteriorly in dorsal view. [7] Caseidae is based on the absence of a ventral midline keel on the posterior presacral central, the presence of a well-developed internal trocater on the femur, and an adductor crest that extends diagonally across the femoral shaft almost to the lateral condyle of the femur. [7] Casea based on the presence of a greatly expanded, fan-shaped ilium with a flat contact to the sacrum. C. broilii based on the lack of any expansion of the proximal tibial head.[7]

Postcranial anatomy of C. broilii was first noted by Williston and he observed that the first two sacral ribs were the same size and that the ilium featured a greatly expanded anterior process and only a moderately expanded posterior one.[7] The cervical were shorter, the dorsal ribs enclosed an enormous torso. The caudal were long and the tail tapered gradually. The pectoral girdle was more gracile. The ilium was broad with a large anterior process. The limbs were more gracile, and the hind limbs were sprawling. The digits were much longer than the Etatarsals.[citation needed]

History and Naming[]

Casea was first named in 1910 by the American paleontologist S.W Williston. He was fascinated by Charles Darwin's work. At the age of 50, the University of Chicago asked Williston to be the head of the new department in Vertebrate Paleontology.[8] Here he began his focus on primitive amphibians and reptiles. In 1907 and 1908 Williston began to publish his work. After a long series of explorations in the Texas Permian, Casea class was discovered along with many other species.[8] In 1913 appeared a memoir on Permo- Carboniferous Vertebrates from New Mexico. The same year saw publication of his important papers on the primitive structures of the mandible in amphibian and reptiles and on the skulls of Arasocelis and Casea.[8] The genus name honors the paleontologist E. C. Case and the type species honors the paleontologist Ferdinand Broili.[9]

Classification[]

Recent[when?] studies have aimed to clarify the ambiguity surrounding the taxonomic classification of Casea broilii and its closest relative Eocasea martini. Part of this effort has included an analysis of the two species currently comprising the genus, C. nicholsi and C. broilii.[10] C. nicholsi is closely related to Caseodides because of the proportions on the tibia and fibula.[10] C. broilii were identified as occupying a more basal position relative to other Caseids. They are closely related to Eocasea martini with preserved sacral and pelvic girdle elements. There are morphological and size similarities between the sacrals and the anterior caudals is larger than the posterior dorsals.[10]

Below is a cladogram representing the evolutionary trends all the way up to and past Casea broilii.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology[]

"Caseidae"" is a family of fossil pelycosaur synapsids known exclusively from Permian beds. Synapsida is a clade that includes pelycosaurs, therapsids, and modern mammals.[11] Caseids are distinguished among the basal synapsids by a stout body with robust fore and hind limbs, and a disproportionately small cranium with a procumbent snout that overhangs the tooth row.[11]

Feeding and diet[]

Casea represents one of the first large and highly successful herbivores among terrestrial reptiles.[12] Among vertebrates this feeding strategy can be subdivided into many categories, including folivory, frugivory, granivory but among early terrestrial vertebrates, it is feeding on leaves, stems, roots and rhizomes. Herbivorous use massive crushing dentition on the palate and mandibles.[6] Caseids belong to the most basal clade of synapside, the Caseasuria, which also includes the small carnivorous eothrydids. Caseids are some of the youngest pelycosaur synapsids that survived to co-exists with more derived therapsids synapsids.[6] In the case of Caseids, herbivory is indicated by the presence of a massive rib cage in the thoracic and dorsal regions, and the expanded trunk extends posteriorly to the pelvic girdle, with large ribs fused to the lumbar vertebrae. This suggests that this feeding strategy originated sometime between the late Pennsylvanian and the Early Permian.[6] Some Caseids show dental specializations, with leaf-like large serrations being present in the marginal dentition.[4]

Locomotion[]

The locomotion of Casea involves a three-vertebra sacrum in early synapsids and no apparent link to body size, we argue that this sacral anatomy was related to more efficient terrestrial locomotion than to increased weight bearing.[7] Selective pressures for weight-bearing or more efficient locomotory styles and increasingly terrestrial lifestyles may have promoted the repeated acquisition of three sacral vertebrae in Synapsida. [7] the development of the third sacral rib attachment to the pelvis in Synapsids may support this hypothesis. [7]

Paleoecology/Stratigraphic Range[]

Casea broilii appears in the record at the beginning of the Vale with two species, successively larger, and one in the upper vale and the other in mid-Choza.[1] The three species, lower Vale, upper Vale, and mid-Choza show increase in size of Casea genus and accompany modification of various skeletal parts.[2] Geologic distribution accounts the family has a fossil record extending from the late Carboniferous until the middle Permian.[2] Their fossil record is best known from equatorial regions in North America, and the higher latitudes in Russia, with more recent finds documenting a much higher diversity of Caseids in Europe than previously thought.[2] Caseidae is one of only two pelycosaur families that survived to coexist with therapsids, having been found in the middle Permian Mexen faunal complex with exceptional preservation.[1]

See also[]

- List of pelycosaurs

- List of therapsids

- Caseidae

- Caseasauria

- Synapsids

- Amniota

- Permian

- Reptiles

- Herbivores

- Eocasea

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Williston, S. W. (1910). "New Permian reptiles: Rhachitomous vertebrae". The Journal of Geology. 18 (7): 585–600. Bibcode:1910JG.....18..585W. doi:10.1086/621786. JSTOR 30078133.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e (1952). "The Evolution of the Permian Vertebrate Chronofauna". Evolution. 6 (2): 181–196. doi:10.2307/2405622. JSTOR 2405622.

- ^ Jump up to: a b ; Littlejohn, John (1973). "Factor Analysis of Caseid Pelycosaurs". The Journal of Geology. 47 (5): 886–891. JSTOR 1303067.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Williston, S.W. (1913). "The Skulls of Araeoscelis and Casea, Permian repitles". The Journal of Geology. 21 (8): 673–689. Bibcode:1913JG.....21..743W. doi:10.1086/622122. JSTOR 30058406. S2CID 140622280.

- ^ Angielczyk, Kenneth D.; Kammerer, Christian F. (2018). "Non-mammalian synapsids: the deep roots of the mammalian family tree". In Zachos, Frank; Asher, Robert (eds.). Mammalian Evolution, Diversity and Systematics. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. pp. 117–198.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Maddin, Hillary; Sidor, Christian; Reisz, Robert (2008). "Cranial Anatomy of Ennatosaura tecton (Synapsida : Caseidae) from the middle Permian of Russia and the Evolutionary Relationships of Caseidae". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28: 160–180. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2008)28[160:CAOETS]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Leblanc, ARH; Reisz, RR (2014). "New Postcranial material of the Early Casied Casea broilii Williston, 1910 with a review of the evolution of the sacrum in Paleozoic Non Mammalian Synapsids". doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0115734.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Osborn, Henry Fairfield (1918). "Samuel Wendell Williston 1852-1918". The Journal of Geology. 26 (8): 673–689. Bibcode:1918JG.....26..673O. doi:10.1086/622630. JSTOR 30063514. S2CID 129085529.

- ^ Lambertz, Markus; Shelton, Cristen D.; Spindler, Frederik; Perry, Steven F. (2016). "A caseian point for the evolution of a diaphragm homologue among the earliest synapsids". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1385 (1): 3–20. Bibcode:2016NYASA1385....3L. doi:10.1111/nyas.13264. PMID 27859325. S2CID 24680688.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Reisz, RR; Frobisch, J (2014). "The oldest cased synapsid form the late Pennsylvanian of Kansas, and the evolution of Herbivory terrestrial vertebrates". doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0094518.

- ^ Jump up to: a b (1910). "New Permian Reptiles: Rhachitomous Vertebrae". The Journal of Geology. 18 (7): 585–600. Bibcode:1910JG.....18..585W. doi:10.1086/621786.

- ^ ; Romano, Marco; Frobisch, Jorg (2017). "Principle component analysis as an alternative treatment for morphometric characters: phylogeny of Caseids as a case study, Dryad, Dataset". doi:10.5061/dryad.qg91m.

- Permian synapsids of Europe

- Lopingian synapsids of North America

- Caseasaur genera

- Taxa named by Samuel Wendell Williston

- Fossil taxa described in 1910

- Prehistoric synapsid stubs