Cent (music)

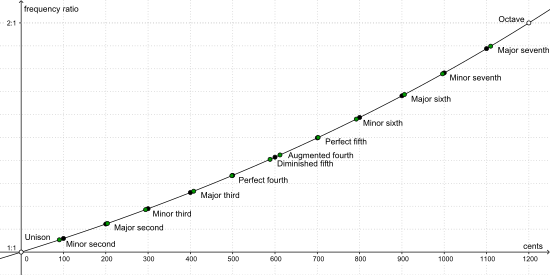

The cent is a logarithmic unit of measure used for musical intervals. Twelve-tone equal temperament divides the octave into 12 semitones of 100 cents each. Typically, cents are used to express small intervals, or to compare the sizes of comparable intervals in different tuning systems, and in fact the interval of one cent is too small to be perceived between successive notes.

Cents, as described by Alexander J. Ellis, follow a tradition of measuring intervals by logarithms that began with Juan Caramuel y Lobkowitz in the 17th century.[a] Ellis chose to base his measures on the hundredth part of a semitone, 1200√2, at Robert Holford Macdowell Bosanquet's suggestion. He made extensive measurements of musical instruments from around the world, using cents extensively to report and compare the scales employed,[1] and further described and employed the system in his 1875 edition of Hermann von Helmholtz's On the Sensations of Tone. It has become the standard method of representing and comparing musical pitches and intervals.[2][3]

Use[]

A cent is a unit of measure for the ratio between two frequencies. An equally tempered semitone (the interval between two adjacent piano keys) spans 100 cents by definition. An octave—two notes that have a frequency ratio of 2:1—spans twelve semitones and therefore 1200 cents. Since a frequency raised by one cent is simply multiplied by this constant cent value, and 1200 cents doubles a frequency, the ratio of frequencies one cent apart is precisely equal to 21⁄1200 = 1200√2, the 1200th root of 2, which is approximately 1.0005777895.

If one knows the frequencies a and b of two notes, the number of cents measuring the interval from a to b may be calculated by the following formula (similar to the definition of a decibel):

Likewise, if one knows a note a and the number n of cents in the interval from a to b, then b may be calculated by:

To compare different tuning systems, convert the various interval sizes into cents. For example, in just intonation, the major third is represented by the frequency ratio 5:4. Applying the formula at the top shows that this is about 386 cents. The equivalent interval on the equal-tempered piano would be 400 cents. The difference, 14 cents, is about a seventh of a half step, easily audible.

Piecewise linear approximation[]

As x increases from 0 to 1⁄12, the function 2x increases almost linearly from 1.00000 to 1.05946. The exponential cent scale can therefore be accurately approximated as a piecewise linear function that is numerically correct at semitones. That is, n cents for n from 0 to 100 may be approximated as 1 + 0.0005946n instead of 2n⁄1200. The rounded error is zero when n is 0 or 100, and is about 0.72 cents high when n is 50, where the correct value of 21⁄24 = 1.02930 is approximated by 1 + 0.0005946 × 50 = 1.02973. This error is well below anything humanly audible, making this piecewise linear approximation adequate for most practical purposes.

Human perception[]

It is difficult to establish how many cents are perceptible to humans; this precision varies greatly from person to person. One author stated that humans can distinguish a difference in pitch of about 5–6 cents.[4] The threshold of what is perceptible, technically known as the just noticeable difference (JND), also varies as a function of the frequency, the amplitude and the timbre. In one study, changes in tone quality reduced student musicians' ability to recognize, as out-of-tune, pitches that deviated from their appropriate values by ±12 cents.[5] It has also been established that increased tonal context enables listeners to judge pitch more accurately.[6] "While intervals of less than a few cents are imperceptible to the human ear in a melodic context, in harmony very small changes can cause large changes in beats and roughness of chords."[7]

When listening to pitches with vibrato, there is evidence that humans perceive the mean frequency as the center of the pitch.[8] One study of modern performances of Schubert's Ave Maria found that vibrato span typically ranged between ±34 cents and ±123 cents with a mean of ±71 cents and noted higher variation in Verdi's opera arias.[9]

Normal adults are able to recognize pitch differences of as small as 25 cents very reliably. Adults with amusia, however, have trouble recognizing differences of less than 100 cents and sometimes have trouble with these or larger intervals.[10]

Centitone[]

A centitone (also Iring) is a musical interval (21⁄600) equal to two cents (22⁄1200)[11][12] proposed as a unit of measurement (![]() Play (help·info)) by Widogast Iring in Die reine Stimmung in der Musik (1898) as 600 steps per octave and later by Joseph Yasser in A Theory of Evolving Tonality (1932) as 100 steps per equal tempered whole tone.

Play (help·info)) by Widogast Iring in Die reine Stimmung in der Musik (1898) as 600 steps per octave and later by Joseph Yasser in A Theory of Evolving Tonality (1932) as 100 steps per equal tempered whole tone.

Iring noticed that the Grad/Werckmeister (1.96 cents, 12 per Pythagorean comma) and the schisma (1.95 cents) are nearly the same (≈ 614 steps per octave) and both may be approximated by 600 steps per octave (2 cents).[13] Yasser promoted the decitone, centitone, and millitone (10, 100, and 1000 steps per whole tone = 60, 600, and 6000 steps per octave = 20, 2, and 0.2 cents).[14][15]

For example: Equal tempered perfect fifth = 700 cents = 175.6 savarts = 583.3 millioctaves = 350 centitones.[16]

| Centitones | Cents |

|---|---|

| 1 centitone | 2 cents |

| 0.5 centitone | 1 cent |

| 21⁄600 | 22⁄1200 |

| 50 per semitone | 100 per semitone |

| 100 per whole tone | 200 per whole tone |

Sound files[]

The following audio files play various intervals. In each case the first note played is middle C. The next note is sharper than C by the assigned value in cents. Finally, the two notes are played simultaneously.

Note that the JND for pitch difference is 5–6 cents. Played separately, the notes may not show an audible difference, but when they are played together, beating may be heard (for example if middle C and a note 10 cents higher are played). At any particular instant, the two waveforms reinforce or cancel each other more or less, depending on their instantaneous phase relationship. A piano tuner may verify tuning accuracy by timing the beats when two strings are sounded at once.

![]() Play middle C & 1 cent above (help·info), beat frequency = 0.16 Hz

Play middle C & 1 cent above (help·info), beat frequency = 0.16 Hz

![]() Play middle C & 10.06 cents above (help·info), beat frequency = 1.53 Hz

Play middle C & 10.06 cents above (help·info), beat frequency = 1.53 Hz

![]() Play middle C & 25 cents above (help·info), beat frequency = 3.81 Hz

Play middle C & 25 cents above (help·info), beat frequency = 3.81 Hz

See also[]

References[]

Footnotes[]

- ^ Caramuel mentioned the possible use of binary logarithms for music in a letter to Athanasius Kircher in 1647; this usage often is attributed to Leonhard Euler in 1739 (see Binary logarithm). Isaac Newton described musical logarithms using the semitone (12√2) as base in 1665; Gaspard de Prony did the same in 1832. Joseph Sauveur in 1701, and Felix Savart in the first half of the 19th century, divided the octave in 301 or 301,03 units. See Barbieri 1987, pp. 145-168 and also Stigler's law of eponymy.

Citations[]

- ^ Ellis 1885.

- ^ Benson 2007, p. 166:The system most often employed in the modern literature.

- ^ Renold 2004, p. 138.

- ^ Loeffler 2006.

- ^ Geringer & Worthy 1999, pp. 135-149.

- ^ Warrier & Zatorre 2002, pp. 198-207.

- ^ Benson 2007, p. 368.

- ^ Brown & Vaughn 1996, pp. 1728–1735.

- ^ Prame 1997, pp. 616-621.

- ^ Peretz & Hyde 2003, pp. 362–367.

- ^ Randel 1999, p. 123.

- ^ Randel 2003, pp. 154, 416.

- ^ "Logarithmic Interval Measures". Huygens-Fokker.org. Retrieved 2021-06-25.

- ^ Yasser 1932, p. 14.

- ^ Farnsworth 1969, p. 24.

- ^ Apel 1970, p. 363.

Sources[]

- Apel, Willi (1970). Harvard Dictionary of Music. Taylor & Francis.

- Barbieri, Patrizio (1987). "Juan Caramuel Lobkowitz (1606–1682): über die musikalischen Logarithmen und das Problem der musikalischen Temperatur". Musiktheorie. 2 (2): 145–168.

- Benson, Dave (2007). Music: A Mathematical Offering. Cambridge. ISBN 9780521853873.

- Brown, J.C.; Vaughn, K.V. (September 1996). "Pitch Center of Stringed Instrument Vibrato Tones" (PDF). Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 100 (3): 1728–1735. Bibcode:1996ASAJ..100.1728B. doi:10.1121/1.416070. PMID 8817899. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- Ellis, Alexander J.; Hipkins, Alfred J. (1884), "Tonometrical Observations on Some Existing Non-Harmonic Musical Scales", Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, 37 (232–234): 368–385, doi:10.1098/rspl.1884.0041, JSTOR 114325, Zenodo: 1432077.

- Ellis, Alexander J. (1885), "On the Musical Scales of Various Nations", Journal of the Society of Arts, retrieved 1 January 2020

- Farnsworth, Paul Randolph (1969). The Social Psychology of Music. ISBN 9780813815473.

- Geringer, J. M.; Worthy, M.D. (1999). "Effects of Tone-Quality Changes on Intonation and Tone-Quality Ratings of High School and College Instrumentalists". Journal of Research in Music Education. 47 (2): 135–149. doi:10.2307/3345719. JSTOR 3345719. S2CID 144918272.

- Loeffler, D.B. (April 2006). Instrument Timbres and Pitch Estimation in Polyphonic Music (Master's). Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Georgia Tech. Archived from the original on 2007-12-18.

- Peretz, I.; Hyde, K.L. (August 2003). "What is specific to music processing? Insights from congenital amusia". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 7 (8): 362–367. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.585.2171. doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(03)00150-5. PMID 12907232. S2CID 3224978.

- Prame, E. (July 1997). "Vibrato extent and intonation in professional Western lyric singing". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 102 (1): 616–621. Bibcode:1997ASAJ..102..616P. doi:10.1121/1.419735.

- Randel, Don Michael (1999). The Harvard Concise Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-00084-1.

- Randel, Don Michael (2003). The Harvard Dictionary of Music (4th ed.). Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01163-2.

- Renold, Maria (2004) [1998], Anna Meuss (ed.), Intervals, Scales, Tones and the Concert Pitch C = 128 Hz, translated by Bevis Stevens, Temple Lodge, ISBN 9781902636467,

Interval proportions can be converted to the cent values which are in common use today

- Warrier, C.M.; Zatorre, R.J. (February 2002). "Influence of tonal context and timbral variation on perception of pitch". Perception & Psychophysics. 64 (2): 198–207. doi:10.3758/BF03195786. PMID 12013375. S2CID 15094971.

- Yasser, Joseph (1932). A Theory of Evolving Tonality. American Library of Musicology.

External links[]

- Cent conversion: Whole number ratio to cent [rounded to whole number]

- Cent conversion: Online utility with several functions

- Equal temperaments

- Intervals (music)

- Units of measurement

- Logarithmic scales of measurement

- 100 (number)