Chechen–Russian conflict

| Chechen–Russian conflict | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Location of the Chechen Republic (red) within the Russian Federation | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Chechen militants and allied groups |

(1991–2017) | ||||||||

|

Including: (2007–17) (1991–2007) (1989–2000) (1940-1944) (1917–22) (1828–59) (1785–1791) |

Including: (1922–91) (1917–22) (1917–20) (1721–1917) | ||||||||

The Chechen–Russian conflict (Russian: Чеченский конфликт, Chechenskiy konflikt; Chechen: Нохчийн-Оьрсийн дов, Noxçiyn-Örsiyn dov) was the centuries-long conflict, often armed, between the Russian (formerly Soviet) government and various Chechen forces. Formal hostilities date back to 1785, though elements of the conflict can be traced back considerably further.[3][4]

The Russian Empire initially had little interest in the North Caucasus itself other than as a communication route to its ally the Kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti (eastern Georgia) and its enemies, the Persian and Ottoman Empires, but growing tensions triggered by Russian activities in the region resulted in an uprising of Chechens against the Russian presence in 1785, followed by further clashes and the outbreak of the Caucasian War in 1817. Russia officially won against the imamate in 1864 but only succeeded in defeating the Chechen forces in 1877.

During the Russian Civil War, Chechens and other Caucasian nations lived in independence for a few years before being Sovietized in 1921. In 1944 on the grounds of dubious allegations of widespread collaboration with the advancing German forces, the Chechen nation as a collective were forcefully transferred to Central Asia in an act of ethnic cleansing.

The most recent conflict between the Chechen and the Russian government took place in the 1990s. As the Soviet Union disintegrated, the Chechen separatists declared independence in 1991. By late 1994 the First Chechen War broke out and after two years of fighting the Russian forces withdrew from the region in December 1996. In 1999, the fighting restarted resulting in yet another major armed conflict culminating in a large number of casualties on both sides with vast destruction of the Chechen capital in the Battle of Grozny that saw the Russian military establishing control over Grozny in early February 2000 officially ending the war with insurgency and hostilities continued in various forms and to varying degrees for several years.[5][6][7] The end of the conflict was proclaimed in 2017, ending a decades-long struggle.[8][9][10]

Origins[]

The North Caucasus, a mountainous region that includes Chechnya, spans or lies close to important trade and communication routes between Russia and the Middle East, control of which have been fought over by various powers for millennia.[11] Russia's entry into the region followed Tsar Ivan the Terrible's conquest of the Golden Horde's Khanates of Kazan and Astrakhan in 1556, initiating a long struggle for control of the North Caucasus routes with other contemporary powers including Persia, the Ottoman Empire and the Crimean Khanate.[12]

During the 16th century, the Russian Tsardom tried to win influence in the North Caucasus by allying themselves with local princes such as the Temryuk of Kabarda and Shikh-Murza Okotsky of Chechnya. Temryuk controlled the Northwest Caucasus and with Russia's help he managed to stave off Crimean incursions. Northeast Caucasus was largely controlled by Shamkhal princes, Avar Khans and the powerful Okotsky lord Shikh-Murza whose influence reached all of Northeast Caucasus. These princes bought weapons and settled Russian Cossacks near the Terek to strengthen their rule and influence. Shikh-Murza Okotsky had in his army around 500 Cossacks combined with 1000 Okocheni (Aukh Chechens), and often waged anti-Iranian and anti-Ottoman campaigns in Dagestan.[13]

Shikh-Murza's politics gave the Russian Tsardom more influence in the Northeast Caucasus, several Russian forts were set up along the Terek river (among them the stronghold of Terki) and Cossack villages.[14] Prior to this the Cossacks had almost no presence in Chechnya and Dagestan. These villages and forts caused Chechens to distrust Shikh-Murza since forts were built on Chechen owned pastures. The Michkizi (lowland Chechens) and part of the Okoki (Aukh Chechens) that were loyal to the Chechen Mullah Mayda joined the outcast Kumyk prince Sultan-Mut who for a very long time allied with the Chechens living south of the Terek-Sulak interfluve. Sultan-Mut was at first against the Russian policies in the Caucasus, he along with the Chechens, Kumyks and Avars fought Russian Cossacks and burned down Russian forts. The Russian Tsar countered this by sending military expeditions into Dagestan, both of these expeditions resulted in Russian defeat and culminated in the Battle of the Karaman Field where a Dagestani-Chechen army under Sultan-Mut defeated the Russian army. These failed expeditions and battles by Russia led to the weakening of Prince Shikh-Murza and his assassination in 1596 by one of Sultan-Mut's brothers.[15][16]

Sultan-Mut continued to pursue an anti-Russian policy into the early 17th century and was known to sometimes live among the Chechens and with them raid the Russian Cossacks.[17] However this started to change as Sultan-Mut several times tried to join the Russians and asked for a citizenship. This switch of policy angered many Chechens and led to them distancing from Sultan-Mut. This caused a mistrust in Aukh between Endireyans (Chechen-Kumyk city controlled by the Sultan-Mut family and his Chechen Sala-Uzden allies) and the Aukh Chechens."[18]

In 1774, Russia gained control of Ossetia, and with it the strategically important Darial Pass, from the Ottomans. A few years later, in 1783, Russia signed the Treaty of Georgievsk with Heraclius II (Erekle) of the Kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti, making the eastern Georgian Kingdom—a Christian enclave surrounded by hostile Muslim states—a Russian protectorate. To fulfill her obligations under the treaty, Catherine the Great, Empress of Russia, began construction of the Georgian Military Road through the Darial Pass, along with a series of military forts to protect the route.[19] These activities, however, antagonized the Chechens, who saw the forts both as an encroachment on the traditional territories of the mountaineers and as a potential threat.[20]

Chechen conflict with the Russian Empire[]

Sheikh Mansur uprising and aftermath, 1785–1794[]

Around this time, Sheikh Mansur, a Chechen imam, began preaching a purified version of Islam and encouraging the various mountain peoples of the North Caucasus to unite under the banner of Islam in order to protect themselves from further foreign encroachments. His activities were seen by the Russians as a threat to their own interests in the region, and in 1785, a force was sent to capture him. Failing to do so, it burned his unoccupied home village instead, but the force was ambushed by Mansur's followers on its return journey and annihilated, beginning the first Chechen–Russian war. The war lasted several years, with Mansur employing mostly guerilla tactics and the Russians conducting further punitive raids on Chechen villages, until Mansur's capture in 1791. Mansur died in captivity in 1794.[21][22]

Caucasian and Crimean Wars, 1817–64[]

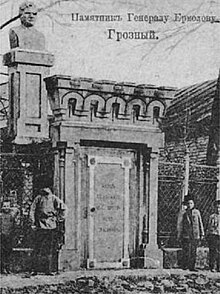

After Russia's defeat of French Napoleonic forces in the 1812 war, Tsar Alexander I turned his attentions once more to the North Caucasus, assigning one of his most celebrated generals, Aleksey Petrovich Yermolov, to the conquest of the region. In 1817, Russian forces under Yermolov's command embarked upon the conquest of the Caucasus.[23] Yermolov's brutal tactics, which included economic warfare, collective punishment and forcible deportations, were initially successful, but have been described as counterproductive since they effectively ended Russian influence on Chechen society and culture and ensured the Chechens' enduring enmity. Yermolov was not relieved of command until 1827.[24][25]

A turning point in the conflict was marked in 1828 when the Muridism movement emerged. It was led by Imam Shamil, a Dagestani Avar. In 1834 he united the Northeast Caucasus nations under Islam and declared "holy war" on Russia.[26] In 1845 Shamil's forces surrounded and killed thousands of Russian soldiers and several generals in Dargo, forcing them to retreat.[26]

During the Crimean War of 1853–6, the Chechens supported the Ottoman Empire against Russia.[26] However, internal tribal conflicts weakened Shamil and he was captured in 1859.[27] The war formally ended in 1862 when Russia promised autonomy for Chechnya and other Caucasian ethnic groups.[27] However, Chechnya and the surrounding region, including northern Dagestan, were incorporated into Russia as the Terek Oblast. Some Chechens have perceived Shamil's surrender as a betrayal, thus created friction between Dagestanis and Chechens in this conflict, with the Dagestanis being frequently accused by Chechens as Russian collaborators.

Russian Civil War and Soviet period[]

After the Russian Revolution, the peoples of the North Caucasus came to establish the Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus. It existed until 1921, when they were forced to accept Soviet rule. Joseph Stalin personally held negotiations with the Caucasian leaders in 1921 and promised a wide autonomy inside the Soviet state. The Mountain Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was created that year, but only lasted until 1924 when it was abolished and six republics were created.[28] The Chechen–Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was established in 1934. Confrontations between the Chechens and the Soviet government arose in the late 1920s during collectivization. It declined by the mid-1930s after local leaders were arrested or killed.[29] The broke out in early 1932 and was defeated in March.

Ethnic cleansing of Chechens from their homeland[]

Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941. Soviet historiography falsely accuses Chechens of joining the Wehrmacht en masse, although this notion is not accepted in any other academic instances.[29] Modern Russian historiography itself also admits that there is little merit to these accusations.[32] By January 1943, the German retreat started, while the Soviet government began discussing the deportation of Chechen and Ingush people far from the North Caucasus, this was despite the fact Chechens and Ingush served in the Red Army like any other of the nations in the Soviet Union. In February 1944, under the direct command of Lavrentiy Beria, almost half a million Chechens and Ingush were removed from their homes and forcibly settled in Central Asia in an act of ethnic cleansing. They were put in forced labor camps in Kazakhstan and Kirghizia.[33] Estimates on casualties range from 170,000[34] up to 200,000,[35] some evidence also indicates that 400,000 people perished,[36] the victims perished mostly due to hypothermia(freezing to death) and starvation, although massacres were not uncommon. The most notable of the massacres during the deportation was the Khaibakh massacre, in which an estimated 700 Chechen children, elderly and women were locked in a barn and burned alive, reportedly due to problems with their transportation.[37] Mikhail Gvishiani, the officer responsible for the massacre was praised and promised a medal by Lavrentiy Beria himself.[37] A 2004 European Parliament resolution states that the deportation was a genocide.[38][39][40]

Ethnic clashes (1958–65)[]

In 1957, Chechens were allowed to return to their homes. The Chechen–Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was reestablished.[41] The violence began in 1958, upon a conflict between a Russian sailor and an Ingush youngster over a girl, in which the Russian was fatally injured. The incident quickly deteriorated into mass ethnic riots, as Slavic mobs attacked Chechens and Ingushes and looted their property throughout the region for 4 days.[42] Ethnic clashes continued through 1960s, and in 1965 some 16 clashes were reported, with 185 severe injuries, 19 of them fatal.[42] By late 1960, the region calmed down and the Chechen–Russian conflict came to its lowest point until the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the eruption of Chechen Wars in 1990.

Post-Soviet era[]

Chechen Wars[]

In 1991, Chechnya declared independence as the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria. According to some sources, from 1991 to 1994, tens of thousands of people of non-Chechen ethnicity (mostly Russians, Ukrainians and Armenians) left the republic amidst reports of violence and discrimination against the non-Chechen population.[43][44][45] Other sources do not identify displacement as a significant factor in the events of the period, instead focusing on the deteriorating domestic situation within Chechnya, the aggressive politics of the Chechyen President, Dzhokhar Dudayev, and the domestic political ambitions of Russian President Boris Yeltsin.[46][47] Russian Army forces were commanded into Grozny in 1994[48] but, after two years of intense fighting, the Russian troops eventually withdrew from Chechnya under the Khasavyurt Accord.[49] Chechnya preserved its de facto independence until the second war broke out in 1999.[50]

In 1999, the Russian government forces started an anti-terrorist campaign in Chechnya, in response to the invasion of Dagestan by Chechen-based Islamic forces.[50] By early 2000 Russia almost completely destroyed the city of Grozny and succeeded in putting Chechnya under direct control of Moscow by late April.[50]

Chechen insurgency[]

Since the end of the Second Chechen War in May 2000, low-level insurgency has continued, particularly in Chechnya, Ingushetia and Dagestan. Russian security forces have succeeded in eliminating some of their leaders, such as Shamil Basayev, who was killed on July 10, 2006.[51] After Basayev's death, Dokka Umarov took the leadership of the rebel forces in North Caucasus until his death owing to poisoning in 2013.[52]

Radical Islamists from Chechnya and other North Caucasian republics have been held responsible for a number of terrorist attacks throughout Russia,[53] most notably the Russian apartment bombings in 1999,[54] the Moscow theater hostage crisis in 2002,[55] the Beslan school hostage crisis in 2004, the 2010 Moscow Metro bombings[56] and the Domodedovo International Airport bombing in 2011.[57]

Currently, Chechnya is now under the rule of its Russian-appointed leader: Ramzan Kadyrov. Though the oil-rich region has maintained relative stability under Kadyrov, he has been accused by critics and citizens of suppressing freedom of the press and violating other political and human rights. Because of this continued Russian rule, there were minor guerilla attacks by separatist groups in the area. Further adding to the tension, jihadist groups aligned with the Islamic State and Al-Qaeda existed in the region.[58]

Although insurgency between the Russian government and the Chechen militants ended in 2017, elimination of militants continued afterwards.[59][60][61][62]

Outside Russia[]

The conflict between Chechens and Russians are also seen outside the Russian border. During the Syrian Civil War, Chechen fighters that remain loyal to the collapsed Chechen Republic of Ichkeria and radical Chechen Islamists had also fought against Russian Army and its ally Bashar al-Assad in Syria, with desire to overthrow the Assad Government and replacing it by a more Chechen-sympathized government.[63][64]

In 2016, Poland, a country which has a history of conflict and tension with Russia, banned Chechen refugees from entering Poland, in a policy to "protect European Union from Islamist terrorism"; Polish interior minister Mariusz Błaszczak had even gone further, blasting the Chechen refugees as dangerous due to its Islamic belief.[65] Poland had already sent back over 78,000 Chechen refugees to Russia in 2016, which was an increase comparing to 18,000 Chechens being denied entry in 2015; as for 2019, the policy had not been reversed.[66][67] The policy of Poland was criticized for being Chechenophobic and supportive of Russia's oppression on Chechens.[68]

On 23 August 2019, Zelimkhan Khangoshvili, a former military commander for the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria during the Second Chechen War, was assassinated in a Berlin park, by an alleged Russian GRU operative.[69] Chechen Republic leader Ramzan Kadyrov is suspected of ordering the assassination of Khangoshvili.[70]

Casualties[]

The exact casualties of this conflict are difficult to ascertain due to lack of records and the long time period of the clashes. One source indicates that at least 60,000 Chechens were killed in the First and Second Chechen War in the 1990s and 2000s alone. [71] High estimates of these two wars range of up to 150,000 or 160,000 killed, as put by Taus Djabrailov, the head of Chechnya's interim parliament.[72]

References[]

- Notes

- Citations

- ^ "Eurasia Overview". Patterns of Global Terrorism: 1999. Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original on 26 April 2009.

Georgia also faced spillover violence from the Chechen conflict...

- ^ Gordon, Michael R. (November 17, 1999). "Georgia Trying Anxiously to Stay Out of Chechen War". The New York Times.

- ^ "Chronology for Chechens in Russia". University of Maryland. Archived from the original on 2013-12-20. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ "Chechnya – Narrative" (PDF). University of Southern California. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-09-02. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

Russian military involvement into the Caucasus started early in the 18th century and in 1785–1791 the first major rebellion in Chechnya against the imperial rule took place.

- ^ "The Dormant Stage of the Chechen Insurgency and the Challenges It Poses to the Pro-Russian Chechen Regime".

- ^ "Insurgency in the North Caucasus: Lessons of the First Chechen War | Small Wars Journal".

- ^ "Ramzan Kadyrov claims the Chechen insurgency is over. Is it?". 18 February 2021.

- ^ Глава ФСБ объявил о ликвидации бандподполья на Северном Кавказе

- ^ Нечаев А., Зайнашев Ю. Россия выиграла еще одну важнейшую битву // , 19.12.2017

- ^ Mark Youngman (June 27, 2017). "Lessons From The Decline Of The North Caucasus Insurgency". crestresearch.ac.uk. Centre For Research and Evidence on Security Threats. Retrieved 2021-01-12.

- ^ Schaefer 2010, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Schaefer 2010, pp. 51–54.

- ^ Адилсултанов, Асрудин (1992). Акки и аккинцы в XVI—XVIII веках. pp. 77–78. ISBN 5766605404.

- ^ Tesaev, Z.A. (2020). К вопросу об этнической картине в Терско-Сулакском междуречье в XIV–XVIII вв. [To the question of ethnic picture in the Tersko-Sulak intercourse in the 14th–18th centuries] (PDF). Bulletin of the Academy of Sciences of the Chechen Republic (in Russian). 48 (1): 72–86. doi:10.25744/vestnik.2020.48.1.011. Retrieved 2020-08-04.

- ^ "Религиозная борьба на территории Чечни и Дагестана (Амин Тесаев) / Проза.ру". proza.ru. Retrieved 2020-08-04.

- ^ Адилсултанов, Асрудин (1992). Акки и аккинцы в XVI—XVIII веках. p. 84. ISBN 5766605404.

- ^ "Neue Seite 39". www.vostlit.info. Retrieved 2020-08-04.

- ^ Адилсултанов, Асрудин (1992). Акки и аккинцы в XVI—XVIII веках. pp. 87–90. ISBN 5766605404.

- ^ Schaefer 2010, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Schaefer 2010, pp. 55–57.

- ^ Schaefer 2010, pp. 55–58.

- ^ Dunlop 1998, pp. 10–13.

- ^ Shultz 2006, p. 115.

- ^ Daniel, pp. 13–18.

- ^ Schaefer 2010, pp. 58–61.

- ^ a b c Shultz 2006, p. 116.

- ^ a b Shultz 2006, p. 117.

- ^ Shultz 2006, p. 118.

- ^ a b Shultz 2006, p. 119.

- ^ "Почему в Грозном дважды сносили памятник Ермолову?". Яндекс Дзен | Платформа для авторов, издателей и брендов. Retrieved 2020-08-02.

- ^ Узел, Кавказский. "Историки констатировали попытки властей России героизировать генерала Ермолова". Кавказский Узел. Retrieved 2020-08-02.

- ^ Ėdiev, D. M. (Dalkhat Muradinovich) (2003). Demograficheskie poteri deportirovannykh narodov SSSR. Stavropolʹ: Izd-vo StGAU "Agrus". p. 28. ISBN 5-9596-0020-X. OCLC 54821667.

- ^ Shultz 2006, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Griffin, Roger (2012). Terrorist's creed : fanatical violence and the human need for meaning. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-137-28472-3. OCLC 812506791.

- ^ Bahcheli, Tozun; Bartmann, Barry; Srebrnik, Henry Felix (2004). De facto states : the quest for sovereignty. London: Routledge. p. 229. ISBN 0-203-48576-9. OCLC 56907941.

- ^ "After 73 years, the memory of Stalin's deportation of Chechens and Ingush still haunts the survivors". OC Media. Retrieved 2020-08-03.

- ^ a b Gammer, M. (2006). The lone wolf and the bear : three centuries of Chechen defiance of Russian rule. London: Hurst & Co. p. 170. ISBN 1-85065-743-2. OCLC 56450364.

- ^ "Texts adopted - Thursday, 26 February 2004 - EU-Russia relations - P5_TA(2004)0121". www.europarl.europa.eu. Retrieved 2020-08-09.

- ^ "UNPO: Chechnya: European Parliament recognises the genocide of the Chechen People in 1944". 2012-06-04. Archived from the original on 2012-06-04. Retrieved 2020-08-09.

- ^ Узел, Кавказский. "European Parliament recognizes deportation of Chechens and Ingushetians ordered by Stalin as genocide". Caucasian Knot. Retrieved 2020-08-09.

- ^ Shultz 2006, p. 121.

- ^ a b Seely, R. Russo-Chechen conflict, 1800–2000: A Deadly Embrace. Frank Cass Publishers. 2001.

- ^ O.P. Orlov; V.P. Cherkassov. "Russia–Chechnya: A chain of mistakes and crimes" Россия — Чечня: Цепь ошибок и преступлений (in Russian). Memorial. Archived from the original on 2017-02-09. Retrieved 2013-09-27.

- ^ Kempton & Clark 2001, p. 122.

- ^ Smith 2005, p. 134.

- ^ King 2008, pp. 234–237.

- ^ Ware 2005, pp. 79–87.

- ^ Kumar 2006, p. 61.

- ^ Kumar 2006, p. 65.

- ^ a b c James & Goetze 2001, p. 169.

- ^ Parsons, Robert (8 July 2006). "Basayev's Death Confirmed". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ Rogio, Bill (25 June 2010). "US designates Caucasus Emirate leader Doku Umarov a global terrorist". Long War Journal. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

After Basayev's death in 2006, the Chechen and Caucasus jihadists united under the command of Doku Umarov, one of the last remaining original leaders of the Chechen rebellion and a close associate of al Qaeda.

- ^ Williams, Carol J. (19 April 2013). "A history of terrorism out of Chechnya". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ^ Feifer, Gregory (9 September 2009). "Ten Years On, Troubling Questions Linger Over Russian Apartment Bombings". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ^ Krechetnikov, Artem (24 October 2012). "Moscow theatre siege: Questions remain unanswered". BBC News. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ^ "Chechen rebel claims Moscow attacks". Al Jazeera. 31 March 2010. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ^ "Chechen warlord Doku Umarov admits Moscow airport bomb". BBC News. 8 February 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ^ "Chechnya profile". BBC News. 17 January 2018.

- ^ "Page doesn't exist".

- ^ "Page doesn't exist".

- ^ "Page doesn't exist".

- ^ Nechepurenko, Ivan; Specia, Megan (19 May 2018). "Gunmen Attack Church in Russia's Chechnya Region, Killing 3". The New York Times.

- ^ "Refworld | Chechens Are Among Foreigners Fighting to Overthrow Bashar al-Assad".

- ^ "Ali ash-Shishani: "Like all Chechens in Syria, I miss Chechnya" | NewСaucasus".

- ^ "Poland slams door on Chechnyan refugees | DW | 31.08.2016".

- ^ "Chechens waiting at Europe's door | DW | 14.12.2016".

- ^ "How and why Chechen refugees are storming the Polish border with Belarus". 4 July 2019.

- ^ "Strasbourg rules against Poland over Chechen migrants".

- ^ "Berlin Chechen shooting: Russian assassination suspected". BBC News. 27 August 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ "Inside the special relationship between Putin and the man responsible for a string of assassinations in Europe". Business Insider. 7 July 2020.

- ^ Crawford & Rossiter 2006, p. 99.

- ^ "Russia: Chechen Official Puts War Death Toll At 160,000". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. August 16, 2005. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

Bibliography[]

- Dunlop, John B. (1998). Russia Confronts Chechnya: Roots of a Separatist Conflict. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521636193.

- Crawford, Marisa; Rossiter, Graham (2006). Reasons for Living: Education and Young People's Search for Meaning, Identity and Spirituality. Aust Council for Ed Research. p. 99. ISBN 9780864316134.

- James, Patrick; Goetze, David (2001). Evolutionary Theory and Ethnic Conflict. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. ISBN 9780275971434.

- Kempton, Daniel R.; Clark, Terry D. (2001). Unity or Separation: Center-Periphery Relations in the Former Soviet Union. Praeger. ISBN 978-0275973063.

- King, Charles (2008). The Ghost of Freedon: A History of the Caucasus. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517775-6.

- Kumar, Rajan (2006). Ethnicity, Nationalism and Conflict Resolution: A Case Study of Chechnya. Gurgaon: Hope India. ISBN 9788178711195.

- Perovic, Jeronim (2018). From Conquest to Deportation. The North Caucasus under Russian Rule. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190889890.

- Schaefer, Robert W. (2010). The Insurgency in Chechnya and the North Caucasus: From Gazavat to Jihad. ABC-CLIO. pp. 49–61. ISBN 9780313386343.

- Shultz, Richard H. (2006). Insurgents, Terrorists, And Militias: The Warriors of Contemporary Combat. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231129824.

- Smith, Sebastian (2005). Allah's Mountains: The Battle for Chechnya. Tauris Parke Paperbacks. ISBN 978-1850439790.

- Ware, Robert Bruce (2005). "A Multitude of Evils: Mythology and Political Failure in Chechnya". In Richard Sakwa (ed.). Chechnya: From Past to Future. London: Anthem Press. pp. 79–115. ISBN 1-84331-165-8.

- Daniel, Elton L. "Golestān Treaty". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- Grant, Thomas D. (2000). "Current Development: Afghanistan Recognizes Chechnya". American University International Law Review. 15 (4): 869–894.

- Chechen–Russian conflict

- Dirty wars

- History of Chechnya

- History of the North Caucasus

- Proxy wars

- Terrorism in Russia

- Wars involving Chechnya

- Wars involving Russia

- Wars of independence

- Violence against indigenous peoples