Chimney sweeps' carcinoma

| Chimney sweeps' carcinoma | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Chimney sweep's cancer Soot wart |

| |

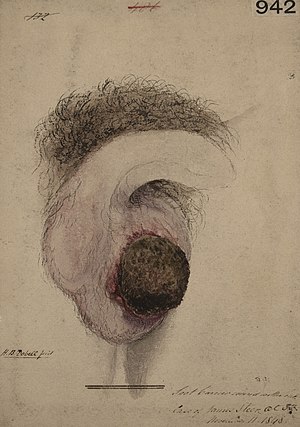

| Watercolour drawing of a case of chimney sweep's cancer. Drawn by Horace Benge Dobell, physician, whilst a student at St Bartholomew's Hospital Medical School. | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

| Symptoms |

|

| Usual onset | 37.7 years |

| Causes | Warts caused by soot irritation develop into cancer |

| Risk factors | Occupational exposure of young male chimney sweeps to soot |

| Treatment | Surgical removal |

Chimney sweep's cancer, also called soot wart, is a squamous cell carcinoma of the skin of the scrotum. It has the distinction of being the first reported form of occupational cancer, and was initially identified by Percivall Pott in 1775.[1] It was initially noticed as being prevalent amongst chimney sweeps.

Pathogenesis[]

Chimney sweeps' carcinoma is a squamous cell carcinoma of the skin of the scrotum. Chimney sweeps' carcinoma was first described by Percivall Pott in 1775 who postulated that the cancer was associated with occupational exposure to soot.[2][3] The cancer primarily affected chimney sweeps who had been in contact with soot since their early childhood. The median age of onset of symptoms in one review was 37.7 years, although boys as young as 8 years old were found to have the disease.[4] It was proposed by W.G. Spencer in 1890 that sweat running down their bodies had caused soot to accumulate in the rugae of the inferior surfaces of the scrotum, with the resulting chronic irritation causing scrotal cancer,[5] but this was shown to be an incorrect artifact of the method used to stain his microscope slides.[4]

In 1922, R.D. Passey, a research physician at Guy's Hospital in London produced malignant skin tumors in mice exposed to an extract made from soot, demonstrating the presence of carcinogenic substances in soot which were the likely cause of cancer of the scrotum in chimney sweeps.[4][6]

In the 1930s Ernest Kennaway and James D. Cook of the Research Institute of the Cancer Hospital in London (later known as the Royal Marsden Hospital), discovered several polycyclic hydrocarbons present in soot that were potent carcinogens: 1,2,5,6-dibenzanthracene; 1,2,7,8-dibenzanthracene; and 1,2-benzpyrene (3) benzo[α]pyrene. DNA consists of sequences of four bases – guanine, adenine, cytosine, and thymine – bound to a deoxyribonucleic backbone, forming the four deoxyribonucleosides: deoxyguanosine etc. Benzo(α)pyrene interacts with deoxyguanosine of the DNA, damaging it and potentially starting the processes that can lead to cancer.[3]

Social context[]

The disease was mostly found in the United Kingdom, where climbing boys were used. An 1875 Act of Parliament forbade this practice. Climbing boys were also used in some European countries.[7] Lord Shaftesbury, a philanthropist, led the later campaign.

In the United States, enslaved black children were hired from their owners and used in the same way, and were still climbing after 1875.[8]

Sir Percivall Pott[]

Sir Percivall Pott (6 January 1714 – 22 December 1788) London, England) was an English surgeon, one of the founders of orthopedy, and the first scientist to demonstrate that a cancer may be caused by an environmental carcinogen. In 1765 he was elected Master of the Company of Surgeons, the forerunner of the Royal College of Surgeons. It was in 1775 that Pott found an association between exposure to soot and a high incidence of chimney sweeps' carcinoma, a scrotal cancer (later found to be squamous cell carcinoma) in chimney sweeps. This was the first occupational link to cancer, and Pott was the first person to demonstrate that a malignancy could be caused by an environmental carcinogen. Pott's early investigations contributed to the science of epidemiology and the Chimney Sweepers Act 1788.[9]

Pott describes chimney sweeps' carcinoma thus:

It is a disease which always makes it first attack on the inferior part of the scrotum where it produces a superficial, painful ragged ill-looking sore with hard rising edges.....in no great length of time it pervades the skin, dartos and the membranes of the scrotum, and seizes the testicle, which it inlarges [sic], hardens and renders truly and thoroughly distempered. Whence it makes its way up the spermatic process into the abdomen.[10]

He comments on the life of the boys:

The fate of these people seems peculiarly hard … they are treated with great brutality … they are thrust up narrow and sometimes hot chimnies [sic], where they are bruised burned and almost suffocated; and when they get to puberty they become … liable to a most noisome, painful and fatal disease.

The suspected carcinogen was coal tar, and possibly arsenic.[11][12]

Treatment[]

Treatment was by surgery.[13]

Related diseases[]

Decades later, it was noticed to occur amongst gas plant and oil shale workers, and it was later found that certain constituents of tar, soot, and oils, known as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, were found to cause cancer in laboratory animals. The related cancer is called mule spinners' cancer.

References[]

- ^ General Surgery Lecture notes, H.Ellis, Wiley Blackwell, 12th edition

- ^ Pott, Percivall (1775). Chirurgical Observations …. London, England: L. Hawes, W. Clarke, and R. Collins. pp. 63–68. From p. 67: "The disease, in these people [i.e., chimney sweeps], seems to derive its origin from a lodgment of soot in the rugae of the scrotum, … "

- ^ a b Dronsfield, Alan (1 March 2006). "Percivall Pott, chimney sweeps and cancer". Education in Chemistry. Vol. 43, no. 2. Royal Society of Chemistry. pp. 40–42, 48. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ^ a b c Waldron 1983.

- ^ Spencer, WG (1890). "Soot in cells of chimney-sweepers' cancer". Medico-Chirurgical Transactions. 1 (74): 59–75.

- ^ Passey, R. D. (1 January 1922). "Experimental Soot Cancer". The British Medical Journal. 2 (3232): 1112–1113. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.3232.1103. JSTOR 20421879. S2CID 220180956.

- ^ Strange 1982, p. 80.

- ^ Strange 1982, p. 93.

- ^ Gordon 1994, p. 128.

- ^ Waldron 1983, p. 391.

- ^ Waldron 1983, p. 390.

- ^ Schwartz 2008, p. 55.

- ^ Waldron 1983, pp. 381, 393.

Bibliography[]

- Curling, Thomas Blizard (1856). A Practical treatise on the diseases of the testis. pp. 409.

- Gordon, Richard (1994). The Alarming History of Medicine. New York: St Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-10411-1.

- Schwartz, Robert A. (2008). Skin Cancer: Recognition and Management (3 ed.). Wiley. p. 55. ISBN 9780470695630.

- Strange, K.H. (1982). Climbing Boys: A Study of Sweeps' Apprentices 1772-1875 (PDF). London/Busby: Allison & Busby. ISBN 0-85031-431-3. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- Waldron, H.A. (1983). "A brief history of scrotal cancer". British Journal of Industrial Medicine. 40 (4): 390–401. doi:10.1136/oem.40.4.390. PMC 1009212. PMID 6354246.

- Carcinoma

- Occupational diseases

- Child labour