China–United Kingdom relations

| |

China |

United Kingdom |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Embassy of China, London | Embassy of the United Kingdom, Beijing |

| Envoy | |

| Ambassador Liu Xiaoming | Ambassador Caroline Wilson |

Chinese-United Kingdom relations (simplified Chinese: 中英关系; traditional Chinese: 中英關係; pinyin: Zhōng-Yīng guānxì), more commonly known as British–Chinese relations, Anglo-Chinese relations and Sino-British relations, refers to the interstate relations between China (with its various governments through history) and the United Kingdom. The United Kingdom and China were on opposing sides of the Cold War. Both countries are permanent members of the United Nations Security Council. The relationship between the two countries has deteriorated since the Hong Kong national security law was passed by China on 30 June 2020.

Chronology[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2021) |

Medieval[]

Rabban Bar Sauma from China visited France and met with King Edward I of England in Gascony.

Between England and the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644)[]

- English ships sailed to Macau in the 1620s, which was leased by China to Portugal. The Unicorn, an English merchant ship, sank near Macau and the Portuguese dredged up sakers (cannon) from the ships and sold those to China around 1620, where they were reproduced as Hongyipao.

- 27 June 1637: Four heavily armed ships under Captain John Weddell, arrived at Macao in an attempt to open trade between England and China. They were not backed by the East India Company, but rather by a private group led by Sir William Courteen, including King Charles I's personal interest of £10,000. They were opposed by the Portuguese authorities in Macao (as their agreements with China required) and quickly infuriated the Ming authorities. Later, in the summer, they captured one of the Bogue forts, and spent several weeks engaged in low-level fighting and smuggling. After being forced to seek Portuguese help in the release of three hostages, they left the Pearl River on 27 December. It is unclear whether they returned home.[1][2][3]

Great Britain and the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911)[]

- 1685 Michael Shen Fu-Tsung visits Britain and meets the king.[4]

- 1793 George Macartney, 1st Earl Macartney led the Macartney Embassy to Peking (Beijing)

- 1816 William Pitt Amherst, 1st Earl Amherst led the Amherst Embassy to China.

- ca. 1820–1830 – British merchants turn Lintin Island in the Pearl River estuary into a centre of opium trade.[5][6]

- 1833-35 As London ended the East India Company's monopoly on trade with China, both Tory and Whig governments sought to maintain peace and good trade relations. However Baron Napier wanted to provoke a revolution in China that would open trade. The Foreign Office, led by Lord Palmerston, stood opposed and sought peace.[7]

- 1839–42 First Opium War, a decisive British victory. British goal was to enforce diplomatic equality and respect. The dominant British position was reflected by the biographer of the foreign minister Lord Palmerston:

- Conflict between China and Britain was inevitable. On the one side was a corrupt, decadent and caste-ridden despotism, with no desire or ability to wage war, which relied on custom much more than force for the enforcement of extreme privilege and discrimination, and which was blinded by a deep-rooted superiority complex into believing that they could assert their supremacy over Europeans without possessing military power. On the other side was the most economically advanced nation in the world, a nation of pushing, bustling traders, of self-help, free trade, and the pugnacious qualities of John Bull.[8]

- An entirely opposite British viewpoint was promoted by humanitarians and reformers such as the Chartists and religious nonconformists led by young William Ewart Gladstone. They argued that Palmerston was only interested in the huge profits it would bring Britain, and was totally oblivious to the horrible moral evils of opium which the Chinese government was valiantly trying to stamp out.[9][10][11]

- 1841 – Convention of Chuenpi, intended to end the war and to cede Hong Kong Island to the British, signed, but never ratified

- 29 August 1842 – Treaty of Nanking ends the war. It includes the cession of Hong Kong Island to the British, and opening of five treaty ports to international trade[12]

- October 1843 – Treaty of the Bogue supplements Treaty of Nanking by granting extraterritoriality to British subjects in China and most favoured nation status to Britain

- 1845–1863 – British Concession in Shanghai established, with the Shanghai International Settlement (1863–1943) replacing the concession soon after.

- 1856–60 Second Opium War

- June 1858 – The Treaty of Tientsin is signed by Lord Elgin

- October 1860 – the sack and destruction of the Old Summer Palace by the victorious British and French troops

- October 1860 – Convention of Peking ends the war. Kowloon Peninsula is ceded to Britain

- 26 March 1861 – In accordance with the treaties, a British legation opens in Beijing (Peking). In the following few years consulates open throughout the Empire, including Hankou (Wuhan), Takao (Kaohsiung), Tamsui (near Taipei), Shanghai and Xiamen.

- 1868 – The Yangzhou riot against Christian missionaries.

- 1870–1900 The telegraph system operated by Britain linked London and the main port cities of China.[13]

- 1875 – The Margary Affair.

- 1877 – A Chinese Legation opens in London under Guo Songtao (Kuo Sung-t'ao)

- 1877–1881 – Britain advises on the Ili Crisis.

- 1886 – After Britain took over Burma, they maintained the sending of tribute to China, putting themselves in a lower status than in their previous relations.[14] It was agreed in the Burma Convention in 1886, that China would recognise Britain's occupation of Upper Burma while Britain continued the Burmese payment of tribute every ten years to Beijing.[15]

- 1888 - War in Sikkim between the British and Tibetans. By the Treaty of Calcutta (1890), China recognises British suzerainty over northern Sikkim.

- 17 March 1890 , fixes the border between Sikkim and Tibet.[16]

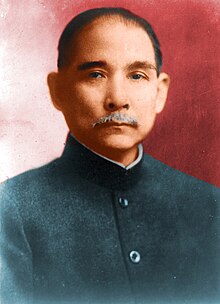

- 1896 – Sun Yat-sen is detained in the Chinese Legation in London. Under pressure from the British public, the Foreign Office secures his release.

- 9 June 1898 – Convention for the Extension of Hong Kong Territory (Second Convention of Peking): New Territories are leased to Britain for 99 years, and are incorporated in Hong Kong

- 1898 – The British obtain a lease on Weihai Harbour, Shandong, to run for as long as the Russians lease Port Arthur. (The reference to the Russians was replaced with one to the Japanese after 1905). An incident occurred where Mail-steamers arrived in Shanghai and dropped off "four young English girls" in December 1898.[17][18][19][20]

- 1900–1901 – The Boxer Rebellion; attacks on foreign missionaries and converts; repressed by Allied counterforce led by Britain and Japan.

- 1901 – The Boxer Protocol

- 1906 – Anglo-Chinese Treaty on Tibet, which London interprets as limiting China to suzerainty over the region

- 1909 – The Japanese Government claims foreign consulates in Taiwan; the British consulates at Tamsui and Takoa close the following year.

Britain and the Republic of China (1912–present)[]

- 1916 – The Chinese Labour Corps recruits Chinese labourers to aid the British during World War I.

- 14 August 1917 – China joins Britain as part of the Allies of World War I.

- 4 May 1919 – The anti-imperialist May Fourth Movement begins in response to the Beiyang government's failure to secure a share of the victory spoils from the leading Allied Powers, after Britain sides with its treaty ally Japan on the Shandong Problem. From this point the ROC leadership moves away from Western models and towards the Soviet Union.

- November 1921 – February 1922. At the Washington naval disarmament conference rivalries persisted over China. The Nine-Power Treaty officially recognized Chinese sovereignty. Japan returned control of Shandong province, of the Shandong Problem, to China.[21]

- 1922-1929: The United States, Japan and Britain supported different warlords. The US and Britain were hostile to the nationalists revolutionary government in Guangzhou (Canton) and supported Chen Jiongming's rebellion. Chinese reactions led to the Northern Expedition (1926–27) which finally unified China under Chiang Kai-shek.[22]

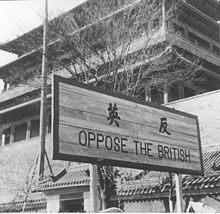

- 30 May 1925 – Shanghai Municipal Police officers under British leadership kill nine people while trying to defend a police station from Chinese protesters, provoking the anti-British campaign known as the May 30 Movement.

- 19 February 1927 – Following riots on the streets of Hankow (Wuhan), the Chen-O'Malley Agreement is entered into providing for the hand over of the British Concession area to the Chinese authorities.

- 1929–1931. The key to Chinese sovereignty was to gain control of tariff rates, which Western powers had set at a low 5%, and to end the extra territoriality by which Britain and the others controlled Shanghai and other treaty ports. These goals were finally achieved in 1928–1931.[23]

- 1930 – Weihai Harbour returned to China.

- 17 May 1935 – Following decades of Chinese complaints about the low rank of Western diplomats, the British Legation in Beijing is upgraded to an Embassy.[24]

- 1936–37 – British Embassy moves to Nanjing (Nanking), following the earlier transfer there of the Chinese capital.

- 1937–41 – British public and official opinion favours China in its war against Japan, but Britain focuses on defending Singapore and the Empire and can give little help. It does provide training in India for Chinese infantry divisions, and air bases in India used by the Americans to fly supplies and warplanes to China.[25]

- 1941–45 – Chinese and British fight side by side against Japan in World War II. The British train Chinese troops in India and use them in the Burma campaign.

- 6 January 1950 – His Majesty's Government (HMG) removes recognition from the Republic of China. The Nanjing Embassy is then wound down. The Tamsui Consulate is kept open under the guise of liaison with the Taiwan Provincial Government.

- 13 March 1972 – The Tamsui Consulate is closed.[26]

- February 1976 – The Anglo Taiwan Trade Committee is formed to promote trade between Britain and Taiwan.[27]

- 30 June 1980 – Fort San Domingo is seized by the Republic of China authorities in lieu of unpaid rent.[26]

- 1989 – The Anglo Taiwan Trade Committee begins issuing British visas in Taipei.

- 1993 – British Trade and Cultural Office opened in Taipei.[28]

- October 2020 – Taiwan (ROC) donates a number of medical masks to the United Kingdom to help fight the COVID-19 pandemic. Donated masks were transferred to the NHS for distribution. The masks are among 7 million donated to European countries.[29]

Between the UK and the People's Republic of China (1949–present)[]

The United Kingdom and the anti-Communist Nationalist Chinese government were allies during World War II. Britain sought stability in China after the war to protect its more than £300 million in investments, much more than from the United States. It agreed in the Moscow Agreement of 1945 to not interfere in Chinese affairs but sympathised with the Nationalists, who until 1947 were winning the Chinese Civil War against the Communist Party of China.[30]

By August 1948, however, the Communists' victories caused the British government to begin preparing for a Communist takeover of the country. It kept open consulates in Communist-controlled areas and rejected the Nationalists' requests that British citizens assist in the defence of Shanghai. By December, the government concluded that although British property in China would likely be nationalised, British traders would benefit in the long run from a stable, industrialising Communist China. Retaining Hong Kong was especially important; although the Communists promised to not interfere with its rule, Britain reinforced the Hong Kong Garrison during 1949. When the victorious Communist government declared on 1 October 1949 that it would exchange diplomats with any country that ended relations with the Nationalists, Britain—after discussions with other Commonwealth members and European countries—formally recognised the People's Republic of China in January 1950.[30]

- 20 April 1949 - The People's Liberation Army attacks HMS Amethyst (F116) travelling to the British Embassy in Nanjing in the Amethyst incident. The Chinese Communists do not recognise the Unequal treaties and protest the ship's right to sail on the Yangtze.[31]

- 6 January 1950 – The United Kingdom recognises the PRC as the government of China and posts a chargé d'affaires ad interim in Beijing (Peking). The British expect a rapid exchange of Ambassadors. However, the PRC demands concessions on the Chinese seat at the UN and the foreign assets of the Republic of China.

- c.1950 – British companies seeking trade with the PRC form the Group of 48 (now China-Britain Business Council).[24][32]

- 1950 – British Commonwealth Forces in Korea successfully defend Hill 282 against Chinese and North Korean forces in the Battle of Pakchon, part of the Korean War.

- 1950 – The Chinese People's Volunteer Army defeat U.N forces, including the British at the Battle of Chosin Reservoir, part of the Korean War

- 1951 – Chinese forces clash with U.N forces including the British at the Imjin River.

- 1951 – Chinese forces attacking outnumbered British Commonwealth forces are held back in the Battle of Kapyong.

- 1951 – British Commonwealth forces successfully capture Hill 317 from Chinese forces in the Battle of Maryang San.

- 1953 – Outnumbered British forces successfully defend Yong Dong against Chinese forces in the Battle of the Hook.

- 1954 – The Sino-British Trade Committee formed as semi-official trade body (later merged with the Group of 48).

- 1954 – A British Labour Party delegation including Clement Attlee visits China at the invitation of then Foreign Minister Zhou Enlai.[33] Attlee became the first high-ranking western politician to meet Mao Zedong.[34]

- 17 June 1954 – Following talks at the Geneva Conference, the PRC agrees to station a chargé d'affaires in London. The same talks resulted in an agreement to re-open a British office in Shanghai, and the grant of exit visas to several British businessmen confined to the mainland since 1951.[35]

- 1961 – The UK begins to vote in the General Assembly for PRC membership of the United Nations. It had abstained on votes since 1950.[36]

- June 1967 – Red Guards break into the British Legation in Beijing and assault three diplomats and a secretary. The PRC authorities refuse to condemn the action. British officials in Shanghai were attacked in a separate incident, as the PRC authorities attempted to close the office there.[37]

- June–August 1967 – Hong Kong 1967 riots. The commander of the Guangzhou Military Region, Huang Yongsheng, secretly suggests invading Hong Kong, but his plan is vetoed by Zhou Enlai.[38]

- July 1967 – Hong Kong 1967 riots – Chinese People's Liberation Army troops fire on British Hong Kong Police, killing 5 of them.

- 23 August 1967 – A Red Guard mob sacks the British Legation in Beijing, slightly injuring the chargé d'affaires and other staff, in response to British arrests of Communist agents in Hong Kong. A Reuters correspondent, Anthony Grey, was also imprisoned by the PRC authorities.[39]

- 29 August 1967 – Armed Chinese diplomats attack British police guarding the Chinese Legation in London.[40]

- 13 March 1972 – PRC accords full recognition to the UK government, permitting the exchange of ambassadors. The UK acknowledges the PRC's position on Taiwan without accepting it.[41]

- 1982 – During negotiations with Margaret Thatcher about the return of Hong Kong, Deng Xiaoping tells her that China can simply invade Hong Kong. It is revealed later (2007) that such plans indeed existed.[38]

- 1984 – Sino-British Joint Declaration.

- 12–18 October 1986 – Queen Elizabeth II makes a state visit to the PRC, becoming the first British monarch to visit China.[42]

- 30 June-1 July 1997 – Transfer of sovereignty over Hong Kong from United Kingdom to China.

- 1997 – China and Britain forge a strategic partnership.[43][unreliable source?][44][failed verification]

- 24 August 2008 – Olympic flag is handed over from the Beijing mayor Guo Jinlong to London mayor Boris Johnson, for the 2012 Summer Olympics in London.

- 29 October 2008 – The UK recognises Tibet as an integral part of the PRC. It had previously only recognised Chinese suzerainty over the region.[45]

- 26 June 2010 – China's paramount leader Hu Jintao invites British Prime Minister David Cameron for talks in Beijing.[46][page needed][original research?]

- 5 July 2010 – Both countries pledge closer military cooperation.[44][47]

- 25 November 2010 – Senior military officials meet in Beijing to discuss military cooperation.[citation needed]

- 26 June 2011 – Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao visits London in order to plan out trade between the two countries which is worth billions of pounds.[48]

- October 2013 – Britain's chancellor George Osborne visits China to look at making new trade links. He says that the UK and China have "much in common" in a speech during his visit.[49]

- June 2014 – Chinese Premier Li Keqiang and his wife Cheng Hong visit UK and meet with Queen Elizabeth II and British Prime Minister David Cameron.[50][51]

- 2015 – UK becomes one of the founder members of the Chinese-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) [52]

- 20–23 October 2015 – China's paramount leader Xi Jinping and First Lady Peng Liyuan undertake a state visit to the United Kingdom, visiting London and Manchester, and meeting with Queen Elizabeth II and David Cameron. More than £30 billion worth of trade deals are also signed on this state visit.[53][54][55]

- July 2016 – China and the UK start a £1.3 million collaboration project on sustainable agricultural technology research, marking the latest addition to farming cooperation between the two countries.[57]

- March 2017 – To mark the occasion of the 45th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations, China Plus, together with Renmin University, invites experts and researchers from China and the UK to discuss the future of bilateral relations.[58]

- February 2018 – British Prime Minister Theresa May visits China on a three-day trade mission and meets with China's paramount leader Xi Jinping, continuing the so-called "Golden Era" of Sino-British relations.[59]

- July 2019 – The UN ambassadors from 22 nations, including UK, signed a joint letter to the UNHRC condemning China's mistreatment of the Uyghurs as well as its mistreatment of other minority groups, urging the Chinese government to close the Xinjiang re-education camps.[60][61]

- June 2020 – The United Kingdom openly opposed the Hong Kong national security law.[62] Lord Patten, who oversaw the handover as governor, said the security law put an end to the "one country, two systems" principle and was a flagrant breach of the agreement between Britain and China.[63]

- 1 July 2020 – British Prime Minister Boris Johnson told the Commons "The enactment and imposition of this National Security law constitutes a clear and serious breach of the Sino-British joint declaration". The British Government pledged to provide three million Hong Kongers holding British National (Overseas) passport a path to full British citizenship.[64]

- 6 July 2020 – China's Ambassador to the United Kingdom Liu Xiaoming said the United Kingdom will "bear the consequences” if it treats China as a “hostile” country in deciding whether to allow telecoms equipment maker Huawei a role in UK 5G phone networks.[65]

- On 20 July 2020, UK government decided to suspend the extradition treaty with China, over the treatment of the Uyghur minority in Xinjiang.[66]

- On 15 August 2020, the UK government suspended its military training with Hong Kong police amid worsening relations with China. Officials from the United Kingdom said the decision was being implemented because of COVID-19 pandemic. However, an MoD spokesperson confirmed that the contracts will be reviewed when the pandemic is over.[67]

- From 1 October 2020, the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office of the British Government expanded the remit of its security vetting for overseas applicants wanting to study subjects relating to national security. The Times said in a report that “The measures are expected to block hundreds of Chinese students from entering Britain. Visas for those already enrolled will be revoked if they are deemed to pose a risk.” [68]

- On 6 October 2020, Germany's ambassador to the UN, on behalf of the group of 39 countries including Germany, the U.K. and the U.S., made a statement to denounce China for its treatment of ethnic minorities and for curtailing freedoms in Hong Kong.[69]

- On 7 October 2020, the UK Parliament's Defence Committee released a report claiming that there was clear evidence of collusion between Huawei and Chinese state and the Chinese Communist Party. The UK Parliament's Defence Committee said that the government should consider removal of all Huawei equipment from its 5G networks earlier than planned.[70]

- On 12 October, the UK began to consider sanctions on China over the breach of Hong Kong by implementing the National Security Law.[71]

- On 22 March 2021, the UK, EU, US and Canada together imposed sanctions on senior Chinese officials involved with the mass detention of Uighur Muslims in Xinjiang province. This marked the first time the UK and EU had sanctioned China since 1989.[72]

- On 25 March, China sanctioned ten UK individuals, including former Conservative Party leader Iain Duncan Smith in retaliation for the sanctions on Chinese officials over Xinjiang.[73]

- On 23 April, MP's led by Sir Iain Duncan Smith passed a motion declaring the mass detention of Uighur Muslims in Xinjiang province a genocide. The United Kingdom is the fourth country in the world to make such action. In response, the Chinese Embassy in London said "The unwarranted accusation by a handful of British MPs that there is 'genocide' in Xinjiang is the most preposterous lie of the century, an outrageous insult and affront to the Chinese people, and a gross breach of international law and the basic norms governing international relations. China strongly opposes the UK's blatant interference in China's internal affairs."[74]

- On 25 April, the China Research Group of Conservative MPs is founded.[75][76]

- On 1 August 2021 the Embassy of China, London criticized the BBC’s coverage of the 2020 Summer Olympics, particularly its Taiwan related coverage. The embassy also condemned a News.com.au article cited by the BBC. The statement said that “The reports on the BBC Chinese website and news.com.au about the participation of ‘Chinese Taipei’ in Tokyo Olympics are unprofessional and severely misleading. The Chinese side is gravely concerned and strongly opposes this.”[77] On 4 August the embassy again criticized the BBC’s coverage of Taiwan’s participation in the Olympics saying that a BBC article explaining the history of Taiwan’s Olympic moniker “Chinese Taipei” had been "sensationalizing the question of the 'Chinese Taipei' team at the Tokyo Olympics.” and went on to state "[China] strongly urges these media to follow international consensus and professional conduct, to stop politicizing sports, and to stop interference with the Tokyo Olympic games."[78]

Diplomacy[]

This section does not cite any sources. (November 2020) |

|

|

Common memberships[]

This section does not cite any sources. (November 2020) |

|

|

Transport[]

Air Transport[]

All three major Chinese airlines, Air China, China Eastern & China Southern fly between the UK and China, principally between London-Heathrow and the three major air hubs of Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. China Southern also flies between Heathrow and Wuhan. Among China's other airlines; Hainan Airlines flies between Manchester and Beijing, Beijing Capital Airlines offers Heathrow to Qingdao, while Tianjin Airlines offers flights between Tianjin, Chongqing and Xi'an to London-Gatwick. Hong Kong's flag carrier Cathay Pacific also flies between Hong Kong to Heathrow, Gatwick and Manchester. The British flag carrier British Airways flies to just three destinations in China; Beijing, Shanghai and Hong Kong, and in the past Chengdu. Rival Virgin Atlantic flies between Heathrow to Shanghai and Hong Kong. British Airways has mentioned that it is interested in leasing China's new Comac C919 in its pool of aircraft of Boeing and Airbus.[82]

Rail Transport[]

In January 2017, China Railways and DB Cargo launched the Yiwu-London Railway Line connecting the city of Yiwu and the London borough of Barking, and creating the longest railway freight line in the world. Hong Kong's MTR runs the London's TfL Rail service and has a 30% stake in South Western Railway. In 2017, train manufacturer CRRC won a contract to build 71 engineering wagons for London Underground. This is the first time a Chinese manufacturer has won a railway contract.[83]

Press[]

The weekly-published Europe edition of China Daily is available in a few newsagents in the UK, and on occasions a condensed version called China Watch is published in the Daily Telegraph.[84] The monthly NewsChina,[85] the North American English-language edition of China Newsweek (中国新闻周刊) is available in a few branches of WHSmith. Due to local censorship, British newspapers and magazines are not widely available in Mainland China, however the Economist and Financial Times are available in Hong Kong.[citation needed]

British "China Hands" like Carrie Gracie, Isabel Hilton and Martin Jacques occasionally write opinion pieces in many British newspapers and political magazines about China, often to try and explain about Middle Kingdom.[citation needed]

Radio and Television[]

Like the press, China has a limited scope in the broadcasting arena. In radio, the international broadcaster China Radio International broadcasts in English over shortwave which isn't widely taken up and also on the internet. The BBC World Service is available in China by shortwave as well, although it is often jammed (See Radio jamming in China). In Hong Kong, the BBC World Service is relayed for eight hours overnight on RTHK Radio 4 which on a domestic FM broadcast.[citation needed]

On television, China broadcasts both its two main English-language news channels CGTN and CNC World. CGTN is available as a streaming channel on Freeview, while both are available on Sky satellite TV and IPTV channels. Mandarin-speaking Phoenix CNE TV is also available of Sky satellite TV. Other TV channels including CCTV-4, CCTV-13, CGTN Documentary,& TVB Europe are available as IPTV channels using set-top boxes.[citation needed]

British television isn't available in China at all, as foreign televisions channels and networks are not allowed to be broadcast in China. On the other hand, there is an interest in British television shows such as Sherlock and British television formats like Britain's Got Talent (China's Got Talent, 中国达人秀) & Pop Idol (Super Girl, 超级女声).[citation needed]

British in China[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2021) |

Statesmen[]

- Sir Robert Hart was a Scots-Irish statesman who served the Chinese Imperial Government as Inspector General of Maritime Customs from 1863 to 1907.

- George Ernest Morrison resident correspondent of The Times, London, at Peking in 1897, and political adviser to the President of China from 1912 to 1920.

Diplomats[]

- Sir Thomas Wade – first professor of Chinese at Cambridge University

- Herbert Giles – second professor of Chinese at Cambridge University

- Harry Parkes

- Sir Claude MacDonald

- Sir Ernest Satow served as Minister in China, 1900–06.

- John Newell Jordan[86] followed Satow

- Sir Christopher Hum

- Augustus Raymond Margary

Merchants[]

- Lancelot Dent

- Keswick family

- William Jardine

Military[]

- Charles George Gordon

Missionaries[]

- Robert Morrison

- Hudson Taylor

- Griffith John

- Cambridge Seven

- Eric Liddell

- Gladys Aylward

Academics[]

- Frederick W. Baller

- James Legge (first professor of Chinese at the University of Oxford)

- Joseph Needham

- Jonathan Spence

Chinese statesmen[]

- Li Hongzhang

- Zhang Zhidong

See also[]

- Foreign relations of the United Kingdom

- History of foreign relations of China

- China Policy Institute

- University of Nottingham Ningbo, China

- Foreign relations of the People's Republic of China

- Foreign relations of Imperial China

- Foreign relations of Hong Kong

- Foreign relations of Macao

- Foreign relations of Taiwan

- British Chinese (Chinese people in the UK)

- Sustainable Agriculture Innovation Network (between the UK and China)

References[]

- ^ Mundy, William Walter (1875). Canton and the Bogue: The Narrative of an Eventful Six Months in China. London: Samuel Tinsley. pp. 51.. The full text of this book is available.

- ^ Dodge, Ernest Stanley (1976). Islands and Empires: Western impact on the Pacific and East Asia (vol.VII). University of Minnesota Press. pp. 261–262. ISBN 978-0-8166-0788-4. Dodge says the fleet was dispersed off Sumatra, and Wendell was lost with all hands.

- ^ J.H.Clapham (1927). "Review of The Chronicles of the East India Company Trading to China, 1635-1834 by Hosea Ballou Morse". The English Historical Review. Oxford University Press. 42 (166): 289–292. doi:10.1093/ehr/XLII.CLXVI.289. JSTOR 551695. Clapham summarizes Morse as saying that Wendell returned home with a few goods.

- ^ "BBC - Radio 4 - Chinese in Britain". www.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ "Shameen: A Colonial Heritage" Archived 2008-12-29 at the Wayback Machine, By Dr Howard M. Scott

- ^ "China in Maps – A Library Special Collection". Archived from the original on December 17, 2008.

- ^ Glenn Melancon, "Peaceful intentions: the first British trade commission in China, 1833–5." Historical Research 73.180 (2000): 33-47.

- ^ Jasper Ridley, Lord Palmerston (1970) p. 249.

- ^ Ridley, 254-256.

- ^ May Caroline Chan, “Canton, 1857” Victorian Review (2010), 36#1 pp 31-35.

- ^ Glenn Melancon, Britain's China Policy and the Opium Crisis: Balancing Drugs, Violence and National Honour, 1833–1840 (2003)

- ^ Koon, Yeewan (2012). "The Face of Diplomacy in 19th-Century China: Qiying's Portrait Gifts". In Johnson, Kendall (ed.). Narratives of Free Trade: The Commercial Cultures of Early US-China Relations. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 131–148.

- ^ Ariane Knuesel, "British diplomacy and the telegraph in nineteenth-century China." Diplomacy and Statecraft 18.3 (2007): 517-537.

- ^ Alfred Stead (1901). China and her mysteries. London: Hood, Douglas, & Howard. p. 100.

- ^ Rockhill, William Woodville (1905). China's intercourse with Korea from the XVth century to 1895. London: Luzac & Co. p. 5.

- ^ "Convention Between Great Britain and China relating to Sikkim & Tibet". Tibet Justice Center.

- ^ Alicia E. Neva Little (10 June 2010). Intimate China: The Chinese as I Have Seen Them. Cambridge University Press. pp. 210–. ISBN 978-1-108-01427-4.

- ^ Mrs. Archibald Little (1899). Intimate China: The Chinese as I Have Seen Them. Hutchinson & Company. pp. 210–.

- ^ [1][permanent dead link]

- ^ Little, Archibald (June 3, 1899). "Intimate China. The Chinese as I have seen them". London : Hutchinson & co. – via Internet Archive.

- ^ https://history.state.gov/milestones/1921-1936/NavalConference

- ^ Erik Goldstein, and John Maurer, The Washington Conference, 1921–22: Naval Rivalry, East Asian Stability and the Road to Pearl Harbor (2012).

- ^ L. Ethan Ellis, Republican foreign policy, 1921-1933 (Rutgers University Press, 1968) , pp 311–321. online

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Britain Recognizes Chinese Communists: Note delivered in Peking". The Times. London. 7 January 1950. p. 6. ISSN 0140-0460.

- ^ J. K. Perry, "Powerless and Frustrated: Britain's Relationship With China During the Opening Years of the Second Sino-Japanese War, 1937–1939," Diplomacy and Statecraft, (Sept 2011) 22#3 pp 408–430,

- ^ Jump up to: a b File documents from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, passim. [2], released in response to a Freedom of Information Act request at Whatdotheyknow.com

- ^ [3]

- ^ "House of Commons - Foreign Affairs - Minutes of Evidence". publications.parliament.uk.

- ^ Ya-chen, Tai. "Mask donation from Taiwan reaches United Kingdom". focustaiwan.tw. Focus Taiwan. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wolf, David C. (1983). "'To Secure a Convenience': Britain Recognizes China – 1950". Journal of Contemporary History. 18 (2): 299–326. doi:10.1177/002200948301800207. JSTOR 260389. S2CID 162218504.

- ^ Malcolm Murfett, Hostage on the Yangtze: Britain, China, and the Amethyst crisis of 1949 (Naval Institute Press, 2014)

- ^ "British Envoy for Peking". The Times. London. 2 February 1950. p. 4. ISSN 0140-0460.

- ^ Mishra, Pankaj (December 20, 2010). "Staying Power: Mao and the Maoists". The New Yorker. Retrieved September 21, 2011.

- ^ "Letter from Mao Zedong to Clement Attlee sells for £605,000". The Guardian. 2015-12-15. Retrieved 2020-01-05.

- ^ "Backgrounder: China and the United Kingdom". Xinhua. 2003. Archived from the original on 2012-10-23. Retrieved 2008-12-10. "Chinese Envoy for London: A chargé d'affaires". The Times. London. 18 June 1955. p. 6. ISSN 0140-0460.

- ^ David C. Wolf, "'To Secure a Convenience': Britain Recognizes China-1950." Journal of Contemporary History (1983): 299–326.

- ^ Harold Munthe-Kaas; Pat Healy (23 August 1967). "Britain's Tough Diplomatist in Peking". The Times. London. p. 6. ISSN 0140-0460.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Revealed: the Hong Kong invasion plan", Michael Sheridan, Sunday Times, June 24, 2007

- ^ "Red Guard Attack as Ultimatum Expires". The Times. London. 23 August 1967. p. 1. ISSN 0140-0460.

- ^ Peter Hopkirk (30 August 1967). "Dustbin Lids Used as Shields". The Times. London. p. 1. ISSN 0140-0460.

- ^ "Backgrounder: China and the United Kingdom". Xinhua. 2003. Archived from the original on 2012-10-23. Retrieved 2008-12-10. "Ambassador to China after 22-year interval". The Times. London. 14 March 1972. p. 1. ISSN 0140-0460.

- ^ "Queen to Visit China". New York Times. 11 September 1986. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ^ "China-UK relations scale new height - People's Daily Online". en.people.cn.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Shaun Breslin, "Beyond diplomacy? UK relations with China since 1997." British Journal of Politics & International Relations 6#3 (2004): 409–425.

- ^ Foreign and Commonwealth Office Written Ministerial Statement on Tibet Archived December 2, 2008, at the Wayback Machine 29 October 2008. Retrieved on 10 December 2008.

- ^ Kerry Brown, What's Wrong With Diplomacy?: The Future of Diplomacy and the Case of China and the UK (Penguin, 2015) ch 1.

- ^ "地址不存在". www.china.org.cn.

- ^ Zheng, Yongnian et al , "China's Foreign Policy: Coping with Shifting Geopolitics and Maintaining Stable External Relations." East Asian Policy 4#1 (2012) pp: 29–42.

- ^ Ross, John (2013). "The New Realities of China-UK Relations". China Today. 12: 15.

- ^ "Cameron hails China links at talks with Li Keqiang". BBC News. 17 June 2014. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- ^ "Chinese Premier Li Keqiang meets the Queen on UK visit". BBC News. 17 June 2014. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- ^ "China-led AIIB development bank holds signing ceremony". BBC News. 2015-06-29. Retrieved 2018-01-02.

- ^ "Hong Kong billionaire puts China UK investments in shade". Financial Times.

- ^ Elgot, Jessica (20 October 2015). "Xi Jinping visit: Queen and Chinese president head to Buckingham Palace – live". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Todd (20 October 2015). "Five places that Chinese President Xi Jinping should visit during his trip to Manchester with David Cameron". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ "What Boris Johnson has said about other countries". 2019-07-24.

- ^ "China-Europe Relations – Headlines, Politics, Business, Culture – China Daily – World – Chinadaily.com.cn". www.chinadaily.com.cn. Retrieved 2017-07-19.

- ^ "China-UK Relations: Forty-Five Years on & the Golden Era_人大重阳网|中国人民大学重阳金融研究院". rdcy-sf.ruc.edu.cn. Retrieved 2017-07-19.

- ^ Xiaoming, Liu (2018). "The UK-China 'Golden Era' can bear new fruit". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 2018-02-01.

- ^ "Which Countries Are For or Against China's Xinjiang Policies?". The Diplomat. 15 July 2019.

- ^ "More than 20 ambassadors condemn China's treatment of Uighurs in Xinjiang". The Guardian. 11 July 2019.

- ^ Lawler, Dave (2 July 2020). "The 53 countries supporting China's crackdown on Hong Kong". Axios. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ "Hong Kong: UK says new security law is 'deeply troubling'". BBC News. 30 June 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ James, William (1 July 2020). "UK says China's security law is serious violation of Hong Kong treaty". Reuters. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ "China envoy warns of 'consequences' if Britain rejects Huawei". Financial Times. 6 July 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ "U.K. suspends extradition treaty with Hong Kong amid public outrage over human rights in China". Washington Post. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ "UK halts military training for Hong Kong police as relations with China decline". The Guardian. 15 August 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- ^ Fisher, Lucy. "Chinese students face ban amid security fears". The Times. Archived from the original on 5 October 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ Wainer, David. "Western Allies Rebuke China at UN Over Xinjiang, Hong Kong". bloomberg. Archived from the original on 7 October 2020. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ^ Corera, Gordon. "Huawei: MPs claim 'clear evidence of collusion' with Chinese Communist Party". BBC. Archived from the original on 14 October 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ Holton, Guy Faulconbridge, Kate (November 12, 2020). "UK to consider sanctions against China for breaching Hong Kong treaty" – via www.reuters.com.

- ^ Possible, We Will Respond as Soon as. "UK sanctions perpetrators of gross human rights violations in Xinjiang, alongside EU, Canada and US". GOV.UK. Retrieved 2021-04-19.

- ^ "Uighurs: China bans UK MPs after abuse sanctions". BBC News. 2021-03-26. Archived from the original on May 14, 2021. Retrieved 2021-04-19.

- ^ "Uyghurs: MPs state genocide is taking place in China". BBC News. 2021-04-23. Retrieved 2021-04-23.

- ^ "Coronavirus: Tory MPs to examine 'rise of China'". BBC News. 25 April 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ Payne, Sebastian (25 April 2020). "Senior Tories launch ERG-style group to shape policy on China". Financial Times. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ Chang, Eric. "Chinese embassy in UK furious over BBC's Taiwan Olympics reporting". www.taiwannews.com.tw. Taiwan News. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ^ Yang, William. "'Chinese Taipei': Taiwan's Olympic success draws attention to team name". www.dw.com. DW. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i The special administrative regions of Hong Kong and Macau have membership of this organisation in their own right, as well as mainland People's Republic of China.

- ^ Jump up to: a b The special administrative region of Hong Kong have membership of this organisation in its own right, as well as mainland People's Republic of China.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d The special administrative regions of Hong Kong and Macau have associated or sub-bureau membership of this organisation in their own right, as well as mainland People's Republic of China.

- ^ 大汉网络. "Air Asia, British Airways considering C919". english.ningbo.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 2018-01-01. Retrieved 2017-12-31.

- ^ Templeton, Dan. "CRRC wins first British contract". International Rail Journal. Retrieved 2017-12-31.

- ^ "China Watch". The Telegraph. 2016-08-17. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 2016-09-15. Retrieved 2017-12-31.

- ^ "NewsChina Magazine". www.newschinamag.com. Retrieved 2017-12-31.

- ^ Kit-ching Chan Lau (1 December 1978). Anglo-Chinese Diplomacy 1906–1920: In the Careers of Sir John Jordan and Yuan Shih-kai. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 168–. ISBN 978-962-209-010-1.

Bibliography[]

- Bickers, Robert A. Britain in China: Community, Culture and Colonialism, 1900-49 (1999)

- Brunero, Donna. Britain's Imperial Cornerstone in China: The Chinese Maritime Customs Service, 1854–1949 (Routledge, 2006). Online review

- Carroll, John M. Edge of empires: Chinese elites and British colonials in Hong Kong (Harvard UP, 2009.)

- Cooper, Timothy S. "Anglo-Saxons and Orientals: British-American interaction over East Asia, 1898–1914." (PhD dissertation U of Edinburgh, 2017). online

- Cox, Howard, and Kai Yiu Chan. "The changing nature of Sino-foreign business relationships, 1842–1941." Asia Pacific Business Review (2000) 7#2 pp: 93–110. online

- Dean, Britten (1976). "British informal empire: The case of China 1". Journal of Commonwealth & Comparative Politics. 14 (1): 64–81. doi:10.1080/14662047608447250.

- Dean, Britten. China and Great Britain: The Diplomacy of Commercial Relations, 1860–1864 (1974)

- Fairbank, John King. Trade and diplomacy on the China coast: The opening of the treaty ports, 1842-1854 (Harvard UP, 1953), a major scholarly study; online

- Gerson, J.J. Horatio Nelson Lay and Sino-British relations. (Harvard University Press, 1972)

- Gregory, Jack S. Great Britain and the Taipings (1969) online

- Gull E. M. British Economic Interests In The Far East (1943) online

- Hanes, William Travis, and Frank Sanello. The opium wars: the addiction of one empire and the corruption of another (2002)

- Hinsley, F.H. ed. British Foreign Policy under Sir Edward Grey (Cambridge UP, 1977) ch 19, 21, 27, covers 1905 to 1916..

- Horesh, Niv. Shanghai's bund and beyond: British banks, banknote issuance, and monetary policy in China, 1842–1937 (Yale UP, 2009)

- Keay, John. The Honourable Company: a history of the English East India Company (1993)

- Kirby, William C. "The Internationalization of China: Foreign Relations at home and abroad in the Republican Era." The China Quarterly 150 (1997): 433–458. online

- Le Fevour, Edward. Western enterprise in late Ch'ing China: A selective survey of Jardine, Matheson and Company's operations, 1842–1895 (East Asian Research Center, Harvard University, 1968)

- Lodwick, Kathleen L. Crusaders against opium: Protestant missionaries in China, 1874–1917 (UP Kentucky, 1996)

- Louis, Wm Roger. British strategy in the Far East, 1919-1939 (1971) online

- McCordock, Stanley. British Far Eastern Policy 1894–1900 (1931) online

- Melancon, Glenn. "Peaceful intentions: the first British trade commission in China, 1833–5." Historical Research 73.180 (2000): 33–47.

- Melancon, Glenn. Britain's China Policy and the Opium Crisis: Balancing Drugs, Violence and National Honour, 1833–1840 (2003) excerpt and text search

- Murfett, Malcolm H. "An Old Fashioned Form of Protectionism: The Role Played by British Naval Power in China from 1860–1941." American Neptune 50.3 (1990): 178–191.

- Porter, Andrew, ed. The Oxford history of the British Empire: The nineteenth century. Vol. 3 (1999) pp 146–169. online

- Ridley, Jasper. Lord Palmerston (1970) pp 242–260, 454–470; online

- Spence, Jonathan. "Western Perceptions of China from the Late Sixteenth Century to the Present" in Paul S. Ropp, ed. Heritage of China: Contemporary Perspectives on Chinese Civilization (1990) excerpts

- Suzuki, Yu. Britain, Japan and China, 1876–1895: East Asian International Relations before the First Sino–Japanese War (Routledge, 2020).

- Swan, David M. "British Cotton Mills in Pre-Second World War China." Textile History (2001) 32#2 pp: 175–216.

- Wang, Gungwu. Anglo-Chinese Encounters since 1800: War, Trade, Science, and Governance (Cambridge University Press, 2003)

- Woodcock, George. The British in the Far East (1969) online

- Yen-p’ing, Hao. The Commercial Revolution in Nineteenth- Century China: the rise of Sino-Western Mercantile Capitalism (1986)

Since 1931[]

- Albers, Martin, ed. Britain, France, West Germany and the People's Republic of China, 1969–1982 (2016) online

- Barnouin, Barbara, and Yu Changgen. Chinese Foreign Policy during the Cultural Revolution (1998).

- Bickers, Robert. Britain in China: Community, Culture and Colonialism, 1900–49 (1999)

- Boardman, Robert. Britain and the People's Republic of China, 1949–1974 (1976) online

- Breslin, Shaun. "Beyond diplomacy? UK relations with China since 1997." British Journal of Politics & International Relations 6#3 (2004): 409–425.0

- Brown, Kerry. What's Wrong With Diplomacy?: The Future of Diplomacy and the Case of China and the UK (Penguin, 2015)

- Buchanan, Tom. East Wind: China and the British Left, 1925–1976 (Oxford UP, 2012).

- Clayton, David. Imperialism Revisited: Political and Economic Relations between Britain and China, 1950–54 (1997)

- Clifford, Nicholas R. Retreat from China: British policy in the Far East, 1937-1941 (1967) online

- Feis, Herbert. The China Tangle (1967), diplomacy during World War II; online free to borrow

- Friedman, I.S. British Relations with China: 1931–1939 (1940) online

- Kaufman, Victor S. "Confronting Communism: U.S. and British Policies toward China (2001) * Keith, Ronald C. The Diplomacy of Zhou Enlai (1989)

- MacDonald, Callum. Britain and the Korean War (1990)

- Mark, Chi-Kwan. The Everyday Cold War: Britain and China, 1950–1972 (2017) online review

- Martin, Edwin W. Divided Counsel: The Anglo-American Response to Communist Victory in China (1986)

- Osterhammel, Jürgen. "British business in China, 1860s–1950s." in British Business in Asia since 1860 (1989): 189–216. online

- Ovendale, Ritchie."Britain, the United States, and the Recognition of Communist China." Historical Journal (1983) 26#1 pp 139–58.

- Porter, Brian Ernest. Britain and the rise of communist China: a study of British attitudes, 1945–1954 (Oxford UP, 1967).

- Rath, Kayte. "The Challenge of China: Testing Times for New Labour’s ‘Ethical Dimension." International Public Policy Review 2#1 (2006): 26–63.

- Roberts, Priscilla, and Odd Arne Westad, eds. China, Hong Kong, and the Long 1970s: Global Perspectives (2017) excerpt

- Shai, Aron. Britain and China, 1941–47 (1999) online.

- Shai, Aron. "Imperialism Imprisoned: the closure of British firms in the People's Republic of China." English Historical Review 104#410 (1989): 88–109 online.

- Silverman, Peter Guy. "British naval strategy in the Far East, 1919-1942 : a study of priorities in the question of imperial defense" (PhD dissertation U of Toronto, 1976) online

- Tang, James Tuck-Hong. Britain's Encounter with Revolutionary China, 1949—54 (1992)

- Tang, James TH. "From empire defence to imperial retreat: Britain's postwar China policy and the decolonization of Hong Kong." Modern Asian Studies 28.2 (1994): 317–337.

- Trotter, Ann. Britain and East Asia 1933–1937 (1975) online.

- Wolf, David C. "`To Secure a Convenience': Britain Recognizes China— 1950." Journal of Contemporary History 18 (April 1983): 299–326. online

- Xiang, Lanxin. Recasting the imperial Far East : Britain and America in China, 1945-1950 (1995) online

Primary sources[]

- Ruxton, Ian (ed.), The Diaries of Sir Ernest Satow, British Envoy in Peking (1900–06) in two volumes, Lulu Press Inc., April 2006 ISBN 978-1-4116-8804-9 (Volume One); ISBN 978-1-4116-8805-6 (Volume Two)fu

External links[]

- China–United Kingdom relations

- British expatriates in China

- Chinese community in the United Kingdom

- Bilateral relations of the United Kingdom

- Bilateral relations of China