Wolf warrior diplomacy

Wolf warrior diplomacy (Chinese: 战狼外交; pinyin: zhànláng-wàijiāo) describes an aggressive style of coercive diplomacy[1] adopted by Chinese diplomats in the 21st century under Chinese leader Xi Jinping's administration. The term was coined from the Chinese action film, Wolf Warrior 2. This approach is in contrast to prior Chinese diplomatic practices of Deng Xiaoping, which had emphasized the avoidance of controversy and the use of cooperative rhetoric.[2][3] Wolf warrior diplomacy is confrontational and combative, with its proponents loudly denouncing any criticism of China on social media and in interviews.[4] As an attempt to gain "discourse power" in international politics, wolf warrior diplomacy forms one part of a new foreign policy strategy called Xi Jinping's "Major Country Diplomacy" (Chinese: 大国外交; pinyin: dàguó-wàijiāo) which has legitimized a more active role for China on the world stage, including engaging in an open ideological struggle with the West.[5][6]

Although the phrase "wolf warrior diplomacy" was popularized as a description of this diplomatic approach during the COVID-19 pandemic, the appearance of wolf warrior-style diplomats had begun a few years prior. Chinese leader and General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party Xi Jinping's foreign policy writ large, perceived anti-China hostility from the West among Chinese government officials, and shifts within the Chinese diplomatic bureaucracy have been cited as factors leading to its emergence.

Overview[]

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

||

|

Policies and theories

Key events

Diplomatic activities

|

||

| ||

When Deng Xiaoping came to power following Mao Zedong's death in the late 1970s, he prescribed a foreign policy summed up with the Chinese idiom tāoguāng-yǎnghuì (Chinese: 韬光养晦; lit. 'to conceal one's light and cultivate in the dark'), and emphasized the avoidance of controversy and the use of cooperative rhetoric. This idiom — which originally referred to biding one's time without revealing one's strength — encapsulated Deng's strategy to "observe calmly, secure our position, cope with affairs calmly, hide our capacities and bide our time, be good at maintaining a low profile, and never claim leadership."[7]

In contrast, China's wolf warrior diplomacy in the 21st century is characterized by the use of confrontational rhetoric by Chinese diplomats,[8][9] coercive behavior,[1] as well their increased willingness to rebuff criticism of China and court controversy in interviews and on social media.[4] It is a departure from former Chinese foreign policy, which focused on working behind the scenes, avoiding controversy and favoring a rhetoric of international cooperation,[10] exemplified by the maxim that China "must hide its strength" in international diplomacy.[11] This change reflects a larger change in how the Chinese government and the CCP relate and interact with the larger world.[12] Efforts aimed at incorporating the Chinese diaspora into China's foreign policy have also intensified with an emphasis placed on ethnic loyalty over national loyalty.[13]

Wolf warrior diplomacy began to emerge in 2017, although components of it had already been incorporated into Chinese diplomacy before then. An assertive diplomatic push resembling wolf warrior diplomacy was also noted following the Great Recession. The emergence of wolf warrior diplomacy has been tied to Xi Jinping's political ambitions and foreign policy inclinations, especially his "Major Country Diplomacy" (Chinese: 大国外交; pinyin: dàguó-wàijiāo), which has legitimized a more active role for China on the world stage, including engaging in open ideological struggle with the West.[5][6] Wolf warrior diplomacy has been attributed to the Xi Jinping Thought on Diplomacy,[14] as well as perceived "anti-China hostility" and fear of "ideological designs" from the West amongst Chinese government officials.[15][11]

When Papua New Guinea hosted the APEC Summit in 2018, four Chinese diplomats barged in uninvited on Rimbink Pato, Papua New Guinea's foreign minister, arguing for changes to the communiqué proclaiming “unfair trade practices” which they felt targeting China. The bilateral discussion was rebuffed as bilateral negotiations with an individual delegation would jeopardise the country's neutrality as host.[16]

In November 2019, Ambassador Gui Congyou threatened Sweden during an interview with broadcaster Swedish PEN saying that “We treat our friends with fine wine, but for our enemies we got shotguns.” over the decision to award Gui Minhai with the Tucholsky Prize. All eight major Swedish political parties have condemned the Ambassador's threats. On December 4 after the prize had been awarded, Ambassador Gui said that one could not both harm China's interests and benefit economically from China. When asked to clarify his remarks he said that China would impose trade restrictions on Sweden, these remarks were backed up by the Chinese Foreign Ministry in Beijing.[17][18][19] The embassy has systematically worked to influence the reporting on China by Swedish journalists.[20] In April 2021 it was revealed that the Chinese embassy threatened a journalist working for the newspaper Expressen. Several political parties publicly expressed that they believe the ambassador should be declared persona non grata and deported. The reason given was that the Chinese embassy, during his time as ambassador, consistently ignores the Swedish constitution by threatening and attempting to influence journalists to not be critical of China.[21]

"Wolf warrior" began to see use as a buzzword during the COVID-19 pandemic.[14] In Europe, leaders have expressed surprise at the Chinese using a diplomatic tone with them that they previously would only have used with small or weak countries, with the messaging shifting from a tone of collaboration to one of opposition.[11]

The Ambassador to France, Lu Shaye, was summoned twice by the French foreign ministry, first in April 2020 over posts and tweets by the embassy defending Beijing's response to the COVID-19 pandemic and criticising the West's handling of it, then in March 2021 over "insults and threats" over new Western sanctions placed on China for its crackdown against the Uyghur minority.[22] Previously as Ambassador to Canada, Shaye accused Canadian media of “Western egotism and white supremacy” and disparaged their work on the ground that they are in a lesser position to judge China's development compared to the Chinese people. He also regularly complained of the "biased" and "slanderous" character of their articles denouncing the persecution of Uyghurs.[23]

One factor which may have helped bring about wolf warrior diplomacy was the addition of a public relations section to internal employee performance reports. This incentivized Chinese diplomats to be active on social media and give controversial interviews. Additionally, a younger cadre of diplomats that worked its way up the ranks of the Chinese diplomatic service and this generational shift is also seen as accounting for part of the change.[24] Activity on social media was greatly increased and the tone of social media engagement became more direct and confrontational.[25] China says wolf warrior diplomacy is a "necessary" response to Western diplomats' social media presences.[4] More specifically, foreign vice-minister Le Yucheng says he believes that foreign countries "are coming to our doorstep, interfering in our family affairs, constantly nagging at us, insulting and discrediting us, [so] we have no choice but to firmly defend our national interests and dignity."[26]

Chinese diplomats engaged in wolf warrior diplomacy during the 2020 Olympics with issue being taken with the way Chinese athletes were being depicted by the media and by the Taiwanese team being introduced as “Taiwan" instead of Chinese Taipei. The Chinese consulate in New York City complained that NBC had used an inaccurate map of China in their coverage because it didn't include Taiwan and the South China Sea.[27]

Etymology[]

The phrase is derived from the title of the patriotic Chinese film Wolf Warrior 2.[25] The tagline of the film was "Whoever attacks China will be killed no matter how far the target is." (Chinese: 犯我中华者,虽远必诛; pinyin: fàn wǒ zhōnghuá zhě, suī yuǎn bì zhū)[28] At the end of the film a cover of the Chinese passport is displayed along with some text, which reads "Citizens of the PRC: When you encounter danger in a foreign land, do not give up! Please remember, at your back stands a strong motherland."[10]

Wolf warrior diplomacy proponents and practitioners[]

Aside from Xi Jinping, Zhao Lijian, Hua Chunying, Wang Wenbin, Hu Xijin, and Liu Xiaoming are also described as prominent proponents of wolf warrior diplomacy.[4]

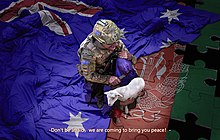

Zhao Lijian and the manipulated image[]

In late 2020, Zhao used his account to circulate a digitally-manipulated image of a child having their throat cut by an Australian soldier in response to the release of the Brereton Report.[29] Global commentators called the tweet "a sharp escalation" in the dispute between China and Australia. Within hours, the image was found to have been created by Wuheqilin, a self-styled Chinese wolf warrior artist.[30]

Reuters reported Prime Minister Scott Morrison describing Zhao's tweet as "truly repugnant" and stating that "the Chinese government should be utterly ashamed of this post. It diminishes them in the world's eyes."[31] The next day, the Chinese foreign ministry rejected Australian demands for an apology.[32] The incident was damaging to Australia–China relations.[33] The effect of Zhao's tweet has been to unify Australian politicians across party lines in condemning the incident and China more generally.[34] On the other hand, Zhao's tweet also garnered a strong wave of Chinese nationalism support in the country, with Wuheqilin's Sina Weibo account doubling in followers to 1.24 million.[35] Security analyst Anthony Galloway later described the event as "a grey zone attack if ever there was one."[36]

Response[]

Wolf warrior diplomacy has often garnered a strong response and in some cases has provoked a backlash against China and specific diplomats.[37] By 2020, The Wall Street Journal was reporting that the rise of wolf warrior diplomacy had left many politicians and businesspeople feeling targeted.[38] An October 2020 survey by the Pew Research Center found that 78% of people in Western nations have "not too much or no confidence" in China's leadership to do the right thing regarding world affairs.[39] In December 2020, Nicolas Chapuis, an ambassador of the European Union to China, warned: "What happened during the last year [...] is a massive disruption or reduction in support in Europe, and elsewhere in the world, about China. And I'm telling that to all my Chinese friends, you need to seriously look at it."[38]

When China threatened Miloš Vystrčil, the president of the Czech Republic's Senate, for addressing Taiwan's national legislature, Reporyje mayor called Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi a Chinese "wolf warrior diplomat".[40]

Cat warrior diplomacy[]

The Taiwanese representative to the United States Hsiao Bi-khim has been described as a "cat warrior"[41] and has started using the term herself.[42][43] Other Taiwanese diplomats have also been characterized as cat warriors for their flexibility and agility. Cat warrior diplomacy is seen as focusing on the soft power aspects of Taiwan's advanced economy, democracy, and respect for human rights as well as using Chinese aggression to highlight the differences between their two political systems.[44] Cat warrior diplomacy aims to use humor and build mutual understanding whereas wolf warrior diplomacy uses threats and ultimatums to coerce a desired response.[45]

See also[]

- 50 Cent Party

- Anti-Western sentiment

- Anti-Western sentiment in China

- Foreign policy of Xi Jinping

- History of foreign relations of China

- Internet Water Army

- Little Pink

- Milk Tea Alliance

- Post–Cold War era

- Second Cold War

- Year Hare Affair

- Xi Jinping Thought on Diplomacy

- Machtpolitik

References[]

- ^ a b Reuters Staff (10 December 2020). "Europe, U.S. should say 'no' to China's 'wolf-warrior' diplomacy - EU envoy". U.S. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ^ Menon, Shivshankar (2 January 2016). "What China's Rise Means for the World". The Wire. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ Son, Daekwon (25 October 2017). "Xi Jinping Thought Vs. Deng Xiaoping Theory". The Diplomat.

- ^ a b c d Jiang, Steven; Westcott, Ben. "China is embracing a new brand of foreign policy. Here's what wolf warrior diplomacy means". CNN. Archived from the original on 29 May 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ a b "China's "Wolf Warrior" Diplomacy in the COVID-19 Crisis". The Asan Forum. 2020-05-15. Retrieved 2022-01-09.

- ^ a b Smith, Stephen (16 February 2021). "China's "Major Country Diplomacy"". Foreign Policy Analysis. doi:10.1093/fpa/orab002. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Dent, C.M. (2010). China, Japan and Regional Leadership in East Asia. Edward Elgar. p. 210. ISBN 978-1-84844-279-5. Retrieved 2021-12-17.

- ^ NAKAZAWA, KATSUJI. "China's 'wolf warrior' diplomats roar at Hong Kong and the world". nikkei.com. Nikkei Asia Review. Archived from the original on 28 May 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ Wu, Wendy (24 May 2020). "Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi defends 'wolf warrior' diplomats for standing up to 'smears'". SCMP. Archived from the original on 27 May 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ a b Syed, Abdul Rasool (14 July 2020). "Wolf warriors: A brand new force of Chinese diplomats". moderndiplomacy.eu. Modern Diplomacy. Archived from the original on 17 July 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ a b c Hille, Kathrin (12 May 2020). "'Wolf warrior' diplomats reveal China's ambitions". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 3 July 2020.

- ^ Zhu, Zhiqun. "Interpreting China's 'Wolf-Warrior Diplomacy'". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ Wong, Brian. "How Chinese Nationalism Is Changing". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 23 August 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ a b Wang, Earl (30 July 2020). "How Will the EU Answer China's Turn Toward 'Xi Jinping Thought on Diplomacy'?". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 31 July 2020.

- ^ Golley, J.; Jaivin, L.; Strange, S. (2021). Crisis. China Story Yearbook. Australian National University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-76046-439-4. Retrieved 2021-12-17.

- ^ "How 'wolf warrior' diplomats have become symbols of the threat posed by a rising China". Stuff. October 16, 2021.

- ^ Olsson, Jojje (December 30, 2019). "China Tries to Put Sweden on Ice". The Diplomat.

- ^ Johan Ahlander, and Cate Cadell, Simon Johnson (November 15, 2019). "China, Sweden escalate war of words over support for detained bookseller". Reuters.

- ^ "Sweden honors detained political writer Gui Minhai despite Chinese threats". Japan Times. November 16, 2019.

- ^ Nyheter, S. V. T.; Kainz Rognerud, Knut; Moberg, Karin; Åhlén, Jon (19 January 2020). "China's large-scale media push: Attempts to influence Swedish media". SVT Nyheter. SVT. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- ^ Gagliano, Alexander (10 April 2021). "V backar utvisningskrav efter ambassadens hot mot reporter - Nyheter (Ekot)". Sveriges Radio (in Swedish).

- ^ "France summons Chinese ambassador over 'unacceptable' tweets". France 24. 2021-03-23. Retrieved 2021-12-19.

- ^ "Chinese diplomat Lu Shaye, the bane of Canadian media, appointed ambassador to France | Reporters without borders". RSF. 2019-06-17. Retrieved 2021-12-19.

- ^ Loh, Dylan M.H (12 June 2020). "Over here, overbearing: The origins of China's 'Wolf Warrior' style diplomacy". hongkongfp.com. Hong Kong Free Press. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ a b Allen-Ebrahimian, Bethany. "China's "Wolf Warrior diplomacy" comes to Twitter". Axios. Archived from the original on 1 July 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ Zhou, Cissy (5 December 2020). "We're not Wolf Warriors, we're only standing up for China, says senior official". SCMP. SCMP. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ Smith, Michael (26 July 2021). "'Wolf warrior' diplomats take issue with Olympics coverage of China". www.afr.com. Australian Financial Review.

- ^ Huang, Zheping (8 August 2017). "China's answer to Rambo is about punishing those who offend China—and it's killing it in theaters". Quartz. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Rej, Abhijnan. "Australia Livid as Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Tweets Offensive Image". The Diplomat. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ "Chinese official tweets doctored image of alleged Australian war crime in Afghanistan, Morrison demands apology". Hindustan Times. 30 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Needham, Kirsty (30 November 2020). "Australia demands apology from China after fake image posted on social media". Reuters. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Hurst, Daniel; Davidson, Helen (30 November 2020). "China rejects Australian PM's call to apologise for 'repugnant' tweet with fake image of soldier". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Hollingsworth, Julia. "Australia demands apology after Chinese official tweets 'falsified image' of soldier threatening child". www.cnn.com. CNN. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Hurst, Daniel; Davidson, Helen; Visontay, Elias (30 November 2020). "Australian MPs unite to condemn 'grossly insulting' Chinese government tweet". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Siow, Maria (4 December 2020). "Australian PM's bid to stir nationalism over Twitter image succeeds – but in China". SCMP. SCMP. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ Galloway, Anthony (2021-05-03). "Military commander tells dark story about the threat from China". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2021-05-04.

- ^ Dupont, Alan. "Who's afraid of the big bad wolves?". The Australian. Archived from the original on 23 August 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ a b Hinshaw, Drew; Norman, Laurence; Sha, Hua (28 December 2020). "Pushback on Xi's Vision for China Spreads Beyond U.S." The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ "Unfavorable Views of China Reach Historic Highs in Many Countries". Pew Research Center's Global Attitudes Project. 6 October 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ "Czech mayor says Chinese behaving like 'unmannered rude clowns', calls FM Wang Yi 'wolf warrior diplomat'".

- ^ Ho, Matt. "New Taiwan envoy to America sees potential risks and rewards in China-US rivalry over economy and tech". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ Everington, Keoni. "Taiwan 'cat warrior' envoy to US ready to fight China's 'wolf warriors'". Taiwan News. Archived from the original on 21 July 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ Liu, Natalie (31 July 2020). "Taiwan's New Envoy to Washington Has Deep Ties to America". The News Lens. Archived from the original on 23 August 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ Glauert, Rik. "Taiwan's 'cat warriors' counter attacks from China's 'wolves'". Nikkei. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ Watt, Louise. "Cat warriors take Taiwan's freedom message to world". The Times. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- Anti-Western sentiment

- Chinese foreign policy

- Foreign relations of China

- People's Republic of China diplomacy

- Xi Jinping

- Chinese nationalism