Zhao Lijian

This article may be expanded with text translated from the corresponding article in Chinese. (March 2020) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Zhao Lijian | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

赵立坚 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Deputy Director of Foreign Ministry Information Department of the People's Republic of China | |||||||

| Assumed office August 2019 Serving with Wang Wenbin | |||||||

| Director | Hua Chunying | ||||||

| Personal details | |||||||

| Born | 10 November 1972 , Luannan County, Hebei[1] | ||||||

| Political party | Communist Party of China (1996–present)[2] | ||||||

| Alma mater | |||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 赵立坚 | ||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 趙立堅 | ||||||

| |||||||

Zhao Lijian (Chinese: 赵立坚; pinyin: Zhào Lìjiān; born 10 November 1972) is a Chinese politician and the deputy director of the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs Information Department. He is the 31st spokesperson since the position was established in 1983.[3] He joined the foreign service in 1996, and has served primarily in Asia. Zhao became notable during his time serving in Pakistan for his outspoken use of Twitter,[4][5] a social network website that is blocked within China. He has been identified as a prominent leader of the new generation of "China's 'Wolf Warrior' Diplomats."[6][7]

Biography[]

Zhao Lijian was born in the town of , in Luannan County, Hebei in November 1972.[3][1] He graduated from Luannan County No. 1 Middle School and Central South University in Changsha, Hunan.[1] He obtained a master's degree in public policy from the Korea Development Institute, where he studied between February and December 2005.[8]

Zhao joined the Department of Asian Affairs in 1996 as an attaché.[8] He was transferred to the Chinese embassy in Pakistan as the attaché to the third secretary in 2003.[8] In 2013, he was recalled to the Department of Asian Affairs. From 2015 to August 2019, he served as counsellor and minister counsellor of the Chinese Embassy in Islamabad. During his tenure there, he used the name "Muhammad Lijian Zhao" on his official Twitter account, but he dropped "Muhammad" in 2017 after there were reports that China banned several Islamic names in Xinjiang.[9]

Zhao became well known for his frequent use of Twitter to criticize the United States, including on topics such as race relations and the United States foreign policy in the Middle East.[10] Paired with his press conference statements, he has established a "long history of provocative assertions."[11] Zhao has been deputy director of Foreign Ministry Information Department of the People's Republic of China since August 2019.[12]

Statements, Twitter and controversies[]

The Chinese Communist Party puts a high premium on information management, and Zhao uses press conferences and Twitter to direct information and reach China's strategic goals.[13][14] Although it had been banned in China in 2009, Zhao joined Twitter in 2010, becoming one of the first envoys of the Chinese government to use the social media platform.[15][16] By the end of 2020, Zhao had 780,000 followers.[17] By that year, Zhao's Twitter account followed the adult entertainment actress Sora Aoi,[18] and Zhao was found to follow Pornhub and Romanian pornographic actress Lea Lexis.[18][19]

"Racist" Washington exchange[]

In 2019 Zhao used Twitter to respond to criticism of his government's policies in southern Xinjiang at the UN by criticising the United States (which had not joined in the criticism at the UN). He wrote in a tweet: "If you're in Washington, D.C., you know the white never go to the SW area, because it's an area for the black & Latin. There's a saying 'black in & white out'", to which Susan Rice, National Security Adviser to Barack Obama, responded: "You are a racist disgrace. And shockingly ignorant too."[20][21] Zhao returned the insults, calling Rice "a disgrace" and "shockingly ignorant" in a tweet as well as calling her accusation of racism "disgraceful and disgusting." Although Zhao stood by the tweets, he deleted them.[22] The dispute raised his profile in Beijing.[23][10]

COVID-19 questions and suggestions[]

On 5 March 2020, Zhao gave a press conference in Beijing and responded to an American TV host's demand that the Chinese should "formally apologize" for the novel coronavirus pandemic. Zhao stated that: "The announcement is absurd and ridiculous, which fully exposes his arrogance, prejudice and ignorance of China... [t]he H1N1 flu outbreak in the United States in 2009 spread to 214 countries and regions and killed at least 18,449 people that year. Has anyone asked the United States to apologize?" He went on to say, "no conclusion has been reached yet on the origin of the virus, as relevant tracing work is still underway."[24][25] From here Zhao turned to Twitter.

On 9 March he condemned United States Secretary of State Mike Pompeo for using the term "Wuhan virus", which was originally used by official Chinese news agencies.[26] Zhao retweeted Americans who were accusing Republicans of racism and xenophobia.[27] On 12 March Zhao appeared to promote a conspiracy theory that the United States military could have brought the novel coronavirus to China.[5][7][27][28][29] On March 12, Zhao tweeted, first in English and separately in Chinese:

When did patient zero begin in US? How many people are infected? What are the names of the hospitals? It might be US army who brought the epidemic to Wuhan. Be transparent! Make public your data! US owe us an explanation![30][31]

The allegation was apparently linked to the United States' participation at the 2019 Military World Games held in Wuhan in October,[28] two months before any reported outbreaks.[31] Zhao accompanied his post with a video of Robert Redfield, director of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, addressing a US Congressional committee on March 11.[5] Redfield had said some Americans who had seemingly died from influenza later tested positive for the new coronavirus.[30] Redfield did not say when those people had died or over what time period.[5] Zhao also linked to article from the Centre for Research on Globalization[27] which BuzzFeed News claimed was part of "a bevy of misinformation about the coronavirus... covered by Global Times, that claimed the virus began in late November somewhere else than Wuhan."[27] The US State Department summoned Chinese ambassador Cui Tiankai on March 13 to protest about Zhao's comments.[31][32] During an interview on Axios on HBO, Cui distanced himself from Zhao's comments and said speculating about the origin of the virus was "harmful".[32] In April 2020, Zhao defended his tweets, saying his posts were "a reaction to some U.S. politicians stigmatizing China a while ago."[33] In July 2021 Zhao made further comments supporting a possible US Army origin for the virus and rejected WHO requests for greater transparency, cooperation, and access to data.[34]

Treatment of Uyghur people[]

Following the leak of the China Cables via The New York Times the Chinese government has come under Western Media's and government's criticism for its treatment of Uyghurs in the Xinjiang re-education camps (since 2017)[35] as methods of confronting Islamist terrorism in Xinjiang[36] lead by Turkistan Islamic Party. Zhao has used media statements and Twitter to defend Beijing's treatment of the minority group.[37] Associated Press claimed that authorities in China were using forced birth control amongst Uyghur people, whilst encouraging larger families of Han Chinese.[38] Responding in an editorial, the Chinese government publication China Daily stated that from 2010 to 2018, the population of Uygur increased by 25.04 percent, and the Han population only 2.0 percent, and that the Uygur population has increased by more than 2.5 million people in eight years.[39][40] Zhao dismissed the findings of AP as "baseless" and showed "ulterior motives."[41] He turned attention back on the media, accusing outlets of "cooking up false information on Xinjiang-related issues".[41] In November 2020, Pope Francis named China's Uyghur minority among a list of the world's persecuted peoples. Zhao retorted that the Pope's words had "no factual basis".[42]

Five Eyes[]

On 19 November 2020, the Five Eyes intelligence-sharing group said China's imposition of new rules to disqualify elected legislators in Hong Kong appeared to be part of a campaign to silence critics and called on Beijing to reverse course.[43] Responding to this, Zhao said that "No matter if they have five eyes or 10 eyes, if they dare to harm China's sovereignty, security and development interests, they should beware of their eyes being poked and blinded".[44]

Brereton Report[]

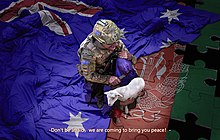

On 30 November 2020, Zhao posted on his personal Twitter account "Shocked by murder of Afghan civilians & prisoners by Australian soldiers. We strongly condemn such acts, &call [sic] for holding them accountable", accompanied with an image of an Australian soldier who appears to hold a bloodied knife against the throat of an Afghan child.[45][46] The image, originally created by the Chinese internet political cartoonist Wuheqilin (乌合麒麟), is believed to be a reference to the Brereton Report, which had been released earlier by the Australian government that month, and which details war crimes committed by the Australian Defence Force during the War in Afghanistan between 2005 and 2016, including the throat-slitting of two 14-year-old Afghan boys, and its subsequent cover-up by the Australian military.[47][48][49] Later that day, the Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison called a press conference, calling the image "offensive" and "truly repugnant",[50] demanding a formal apology from the Chinese government and requesting Twitter to remove the tweet. China rejected the demands for an apology on the following day,[51] while Twitter also refused Morrison's request to remove Zhao Lijian's tweet.[52] The artist behind the illustration said it was created "as a metaphor".[53] Eventually, Morrison called for stopping further amplification of the incident.[54][55] and seek conciliation.[56] The incident had the effect of unifying Australian politicians in condemning China across party lines, while also drawing attention to the Brereton Report.[48] It was further seen as a sign of deteriorating relations between Australia and China.[57]

The New Zealand and French governments voiced support for the Australian government and criticised Zhao's Twitter post,[58][59][60] while the Russian government stated that "the circumstances make us truly doubt the genuine capacity of Australian authorities to actually hold accountable all the servicemen who are guilty of such crimes".[61] The Chinese embassy in Paris criticized the French government's position as hypocrisy, and argued that Chinese artists have the right to caricature, referencing the French government's defense of the Charlie Hebdo caricatures. A spokesperson for the US State Department likewise accused the Chinese foreign ministry of hypocrisy for using Twitter at all when it is blocked in China.[62] The Taiwanese government expressed concern about the Chinese foreign ministry's use of a manipulated image in an official tweet.[63] A week after the tweet an Israeli cybersecurity firm concluded that they had found "evidence of a largely orchestrated disinformation campaign" aimed at spreading the tweet and China's viewpoint. The firm concluded that of the Twitter accounts which had augmented proliferation of the image, "half were likely fake."[64][65]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ a b c "Luannan ren chule yiwei yinghe waijiaoguan, sanjuhua ling Meiguo yakouwuyan" 滦南人出了一位硬核外交官,三句话令美国哑口无言 [Person from Luannan becomes hardline diplomat, leaving the United States speechless in three sentences]. The Paper (in Chinese (China)). 28 March 2020. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ "CV of Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian".

- ^ a b Huang, Yuqin (24 February 2020). "Waijiaobu xinren fayanren Zhao Lijian liangxiang xi zishen waijiaoguan lüli fengfu" 外交部新任发言人赵立坚亮相 系资深外交官履历丰富 [New Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian makes his debut, an experienced diplomat with a strong resume]. China News Service (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ^ Churchill, Owen (24 August 2019). "Chinese diplomat Zhao Lijian, known for his Twitter outbursts, is given senior foreign ministry post". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d Wescott, Ben; Jiang, Steven (14 March 2020). "Chinese diplomat promotes conspiracy theory that US military brought coronavirus to Wuhan". CNN. Archived from the original on 13 March 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ Deng, Chun Han Wong and Chao (2020-05-19). "China's 'Wolf Warrior' Diplomats Are Ready to Fight". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2020-06-19.

- ^ a b Rupakjyoti Borah (May 13, 2020). "Why China's 'Wolf Warrior Diplomacy' Will Backfire". Japan Forward. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ a b c "CV of Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China. 24 February 2020. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ^ Taylor, Adam (July 15, 2019). "A Chinese diplomat had a fight about race in D.C. with Susan Rice on Twitter. Then he deleted the tweets". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b Smith, Ben (2 December 2019). "Meet The Chinese Diplomat Who Got Promoted For Trolling The US On Twitter". BuzzFeed News. Beijing.

- ^ Rej, Abhijnan. "Australia Livid as Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Tweets Offensive Image". thediplomat.com. Retrieved 2020-12-11.

- ^ Yue, Huairang (23 August 2019). "Zhao Lijian churen Waijiaobu xinwensi fusizhang" 赵立坚出任外交部新闻司副司长 [Zhao Lijian appointed Deputy Director of Foreign Ministry Information Department]. The Paper (in Chinese (China)). Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ^ DiResta, Renée (2020-04-11). "For China, the 'USA Virus' Is a Geopolitical Ploy". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2020-12-10.

- ^ "Tweet storm shows China aims to project power through provocation". The Strategist. 2020-12-08. Retrieved 2020-12-10.

- ^ "China blocks Twitter, Flickr, YouTube and Hotmail ahead of Tiananmen anniversary". The Guardian. 2009-06-02. Retrieved 2020-12-10.

- ^ "Twitter has become a new battleground for China's wolf-warrior diplomats | Jing Zeng". The Guardian. 2020-12-02. Retrieved 2020-12-10.

- ^ Winning, David (2020-11-30). "Chinese 'Wolf Warrior' Diplomat Enrages Australia With Twitter Post". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2020-12-10.

- ^ a b News, Taiwan (11 September 2020). "China Foreign Ministry spokesman caught following adult film stars on Twitter". Taiwan News. Retrieved 2020-10-01.

- ^ "Foreign ministry mocked for false claim of China's 'four new inventions'". Apple Daily. Archived from the original on 2021-02-02. Retrieved 2020-10-01.

- ^ Kuo, Lily (17 July 2019). "China's envoys try out Trump-style Twitter diplomacy". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Zhou, Laura (4 August 2019). "Chinese officials discover Twitter. What could possibly go wrong?". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 2020-11-30.

- ^ Taylor, Adam. "A Chinese diplomat had a fight about race in D.C. with Susan Rice on Twitter. Then he deleted the tweets". Washington Post.

- ^ Zhai, Keith; Tian, Yew Lun (31 March 2020). "In China, a young diplomat rises as aggressive foreign policy takes root". Reuters. Archived from the original on 22 April 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ Hall, Louise (12 March 2020). "Coronavirus conspiracy theory that Covid-19 originated in US spreading in China". The Independent.

- ^ "China Destroyed Incriminating Documents on Gross Mishandling of Wuhan Virus". Japan Forward. January 11, 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ^ Hiroshi Yuasa (April 8, 2020). "Why Protest, China? The Term 'Wuhan Virus' Came from Beijing, Not Elsewhere". Japan Forward. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Chinese Diplomats Are Pushing Conspiracy Theories That The Coronavirus Didn't Originate In China". BuzzFeed News. 13 March 2020.

- ^ a b Zheng, Sarah (13 March 2020). "Chinese foreign ministry spokesman tweets claim US military brought coronavirus to Wuhan". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Finnegan, Connor (14 March 2020). "False claims about sources of coronavirus cause spat between the US, China". ABC News. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ a b Yew, Lun Tian; Lee, Se Young; Crossley, Gabriel (13 March 2020). "China sidesteps spokesman's claim of U.S. role in coronavirus outbreak". Reuters.

- ^ a b c Myers, Steven Lee (13 March 2020). "China Spins Tale That the U.S. Army Started the Coronavirus Epidemic". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Zhou, Viola (23 March 2020). "Coronavirus barbs help nobody, China's Washington ambassador says after 'US army' tweets". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ "China Spokesman Defends Virus Tweets Criticized by Trump". Bloomberg. 7 April 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ Tiezzi, Shannon. "China Rejects WHO Call for More Transparency on Origins Probe". thediplomat.com. The Diplomat. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ "Why Don't We Care About China's Uighur Muslims?". The Intercept. December 29, 2019. Retrieved 2020-12-11.

- ^ Yazici, Sheena Chestnut Greitens, Myunghee Lee, and Emir (2020-03-04). "Understanding China's 'preventive repression' in Xinjiang". Brookings. Retrieved 2020-12-21.

- ^ "China's envoys try out Trump-style Twitter diplomacy". The Guardian. 2019-07-17. Retrieved 2020-12-11.

- ^ "China cuts Uighur births with IUDs, abortion, sterilization". AP NEWS. 2020-06-29. Retrieved 2020-12-11.

- ^ 单学英. "So-called Xinjiang population report full of lies". global.chinadaily.com.cn. Retrieved 2020-12-21.

- ^ "China Focus: Xinjiang sees higher growth of Uygur population - Xinhua | English.news.cn". www.xinhuanet.com. Retrieved 2020-12-21.

- ^ a b "China forcing birth control on Uighurs to suppress population, report says". BBC News. 2020-06-29. Retrieved 2020-12-11.

- ^ "China dismisses Pope Francis's comments about persecution of Uighurs". The Guardian. 25 November 2020.

- ^ "'Five Eyes' alliance urges China to end crackdown on Hong Kong legislators". Reuters. 19 December 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ "China says Five Eyes alliance will be 'poked and blinded' over Hong Kong stance". The Guardian. 20 December 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ Needham, Kirsty (2020-12-02). "China's WeChat blocks Australian PM in doctored image dispute". Reuters. Retrieved 2020-12-13.

- ^ "Chinese artist behind doctored image of Australian soldier says he's ready to make more". www.abc.net.au. 2020-12-01. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

Mr Fu created the controversial computer graphic on the evening of November 22

- ^ "China and Australia are in a nasty diplomatic spat over a fake tweet — and real war crimes". Vox. 2 December 2020.

- ^ a b Hurst, Daniel; Davidson, Helen; Visontay, Elias (30 November 2020). "Australian MPs unite to condemn 'grossly insulting' Chinese government tweet". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Withers, Rachel (2020-12-01). "How China Trolled Australia Into Publicizing Its Own War Crimes". Slate Magazine. Retrieved 2020-12-20.

- ^ Needham, Kirsty (30 November 2020). "Australia demands apology from China after fake image posted on social media". Reuters.

- ^ Taipei, Daniel Hurst Helen Davidson in (2020-11-30). "China rejects Australian PM's call to apologise for 'repugnant' tweet". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-12-11.

- ^ "Twitter rejects call to remove Chinese official's fake Australian troops tweet". France 24. 2020-12-01. Retrieved 2021-11-11.

- ^ "China doubles down on criticising Australia over actions in Afghanistan". South China Morning Post. 2020-12-01. Retrieved 2020-12-20.

- ^ "'No further amplification' of shocking China tweet, PM urges". The New Daily. 2020-12-01. Retrieved 2020-12-20.

- ^ "Don't fuel China anger: ScoMo". PerthNow. 2020-12-01. Retrieved 2020-12-20.

- ^ "Australia seeks conciliation with China after dispute over graphic tweet". Los Angeles Times. 2020-12-03. Retrieved 2020-12-20.

- ^ Julia Hollingsworth. "Australia demands apology after Chinese official tweets 'falsified image' of soldier threatening child". CNN. Retrieved 2020-12-11.

- ^ Patterson, Jane (1 December 2020). "New Zealand registers concern with China over official's 'unfactual' tweet". Radio New Zealand. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ^ Hurst, Daniel (1 December 2020). "France and New Zealand join Australia's criticism of Chinese government tweet". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ "Editorial: Use of Fake Photo vs Australia Brings China Diplomacy to New Low". Japan Forward. 7 December 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ Greene, Andrew (2020-11-30). "Russia accused of 'hypocrisy' after attacking Australia over Afghanistan war crimes report". ABC News. Retrieved 2020-12-28.

- ^ Zhou, Laura. "US and France weigh in on bitter China-Australia tweet row over Afghanistan image but Beijing holds firm". SCMP. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ Needham, Kirsty. "China's WeChat blocks Australian PM in doctored image dispute". www.reuters.com. Reuters. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ^ "Likely fake accounts propel China tweet that enraged Australia". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2020-12-06.

- ^ Needham, Kirsty Needham. "China tweet that enraged Australia propelled by 'unusual' accounts, say experts". www.reuters.com. Reuters. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

External links[]

- 1972 births

- Living people

- People's Republic of China politicians from Hebei

- Chinese Communist Party politicians from Hebei

- Spokespersons for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China

- Chinese expatriates in Pakistan