Charlie Hebdo

It has been suggested that this article be split into multiple articles. (Discuss) (October 2020) |

| Type | Satirical weekly news magazine |

|---|---|

| Format | Berliner |

| Owner(s) | Laurent "Riss" Sourisseau (70%), Éric Portheault (30%)[1] |

| Editor | Gérard Biard |

| Founded | 1970[2] |

| Political alignment | Left-wing |

| Ceased publication | 1981 |

| Relaunched | 1992 |

| Headquarters | Paris, France |

| Circulation | ∼55,000 (as of September 2020)[3] |

| ISSN | 1240-0068 |

| Website | CharlieHebdo.fr |

Charlie Hebdo (French pronunciation: [ʃaʁli ɛbdo]; French for Charlie Weekly) is a French satirical weekly magazine,[4] featuring cartoons,[5] reports, polemics, and jokes. Stridently non-conformist in tone, the publication has been described as anti-racist,[6] sceptical,[7] secular, and within the tradition of left-wing radicalism,[8][9] publishing articles about the far-right (especially the French nationalist National Front party),[10] religion (Catholicism, Islam and Judaism), politics and culture.

The magazine has been the target of three terrorist attacks: in 2011, 2015, and 2020. All of them were presumed to be in response to a number of cartoons that it published controversially depicting Muhammad. In the second of these attacks, 12 people were killed, including publishing director Charb and several other prominent cartoonists.

Charlie Hebdo first appeared in 1970 after the monthly Hara-Kiri magazine was banned for mocking the death of former French president Charles de Gaulle.[11] In 1981, publication ceased, but the magazine was resurrected in 1992. The magazine is published every Wednesday, with special editions issued on an unscheduled basis.

Gérard Biard is the current editor-in-chief of Charlie Hebdo.[12] The previous editors were François Cavanna (1970–1981) and Philippe Val (1952–2009).

History[]

Origins in Hara-Kiri[]

In 1960, Georges "Professeur Choron" Bernier and François Cavanna launched a monthly magazine entitled Hara-Kiri.[13] Choron acted as the director of publication and Cavanna as its editor. Eventually Cavanna gathered together a team which included Roland Topor, Fred, Jean-Marc Reiser, Georges Wolinski, Gébé, and Cabu. After an early reader's letter accused them of being "dumb and nasty" ("bête et méchant"), the phrase became an official slogan for the magazine and made it into everyday language in France.

Hara-Kiri was briefly banned in 1961, and again for six months in 1966. A few contributors did not return along with the newspaper, such as Gébé, Cabu, Topor, and Fred. New members of the team included , , and Willem.

In 1969, the Hara-Kiri team decided to produce a weekly publication – on top of the existing monthly magazine – which would focus more on current affairs. This was launched in February as Hara-Kiri Hebdo and renamed L'Hebdo Hara-Kiri in May of the same year.[14] (Hebdo is short for hebdomadaire – "weekly")

Launch of Charlie Hebdo[]

In November 1970, the former French president Charles de Gaulle died in his home village of Colombey-les-Deux-Églises, eight days after a disaster in a nightclub, the Club Cinq-Sept fire, which had caused the death of 146 people. The magazine released a cover spoofing the popular press's coverage of this disaster, headlined "Tragic Ball at Colombey, one dead."[13] As a result, the weekly was banned.

In order to sidestep the ban, the editorial team decided to change its title, and used Charlie Hebdo.[2] The new name was derived from a monthly comics magazine called Charlie (later renamed Charlie Mensuel, meaning Charlie Monthly), which had been started by Bernier and Delfeil de Ton in 1969. The monthly Charlie took its name from the lead character of one of the comics it originally published, Peanuts's Charlie Brown. Using that title for the new weekly magazine was also an inside joke about Charles de Gaulle.[15][16][17] The first issue did feature a Peanuts strip, as the editors were fans of the series.[18]

In December 1981, publication ceased.[19]

Rebirth[]

In 1991, Gébé, Cabu, and others were reunited to work for La Grosse Bertha, a new weekly magazine resembling Charlie Hebdo, created in reaction to the First Gulf War and edited by singer and comedian Philippe Val. However, the following year, Val clashed with the publisher, who wanted apolitical humour, and was fired. Gébé and Cabu walked out with him and decided to launch their own paper again. The three called upon Cavanna, Delfeil de Ton, and Wolinski, requesting their help and input. After much searching for a new name, the obvious idea of resurrecting Charlie Hebdo was agreed on. The new magazine was owned by Val, Gébé, Cabu, and singer Renaud. Val was editor; Gébé was publication director.

The publication of the new Charlie Hebdo began in July 1992 amidst much publicity. The first issue under the new publication sold 100,000 copies. Choron, who had fallen out with his former colleagues, tried to restart a weekly Hara-Kiri, but its publication was short-lived. Choron died in January 2005.

On 26 April 1996, François Cavanna, Charb and Philippe Val filed 173,704 signatures, obtained in eight months, with the aim of banning the political party Front National, since it would have contravened the articles 1, 2, 4, 6, and 7 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.[20]

In 2000, journalist Mona Chollet was sacked after she had protested against a Philippe Val article which called Palestinians "non-civilised".[21] In 2004, following the death of Gébé, Val succeeded him as director of publication, while still holding his position as editor.[22]

In 2008, controversy broke over a column by veteran cartoonist Siné which led to accusations of antisemitism and Siné's sacking by Val. Siné successfully sued the newspaper for unfair dismissal and Charlie Hebdo was ordered to pay him €90,000 in damages.[23] Siné launched a rival paper called which later became . In 2009, Philippe Val resigned after being appointed director of France Inter, a public radio station to which he has contributed since the early 1990s. His functions were split between two cartoonists, Charb and Riss. Val gave away his shares in 2011.

Controversy[]

2006 publication[]

Controversy arose over the publication's edition of 9 February 2006. Under the title "Mahomet débordé par les intégristes" ("Muhammad overwhelmed by fundamentalists"), the front page showed a cartoon of a weeping Muhammad saying "C'est dur d'être aimé par des cons" ("it's hard being loved by jerks"). The newspaper reprinted the twelve cartoons of the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy and added some of their own. Compared to a regular circulation of 100,000 sold copies, this edition enjoyed great commercial success. 160,000 copies were sold and another 150,000 were in print later that day.

In response, French President Jacques Chirac condemned "overt provocations" which could inflame passions. "Anything that can hurt the convictions of someone else, in particular religious convictions, should be avoided", Chirac said. The Grand Mosque of Paris, the Muslim World League and the Union of French Islamic Organisations (UOIF) sued, claiming the cartoon edition included racist cartoons.[24] A later edition contained a statement by a group of twelve writers warning against Islamism.[25]

The suit by the Grand Mosque and the UOIF reached the courts in February 2007. Publisher Philippe Val contended "It is racist to imagine that they can't understand a joke," but Francis Szpiner, the lawyer for the Grand Mosque, explained the suit: "Two of those caricatures make a link between Muslims and Muslim terrorists. That has a name and it's called racism."[26]

Future president Nicolas Sarkozy sent a letter to be read in court expressing his support for the ancient French tradition of satire.[27] François Bayrou and future president François Hollande also expressed their support for freedom of expression. The French Council of the Muslim Faith (CFCM) criticised the expression of these sentiments, claiming that they were politicising a court case.[28]

On 22 March 2007, executive editor Val was acquitted by the court.[29] The court followed the state attorney's reasoning that two of the three cartoons were not an attack on Islam, but on Muslim terrorists, and that the third cartoon with Muhammad with a bomb in his turban should be seen in the context of the magazine in question, which attacked religious fundamentalism.[30]

2011 firebombing[]

In November 2011, the newspaper's office in the 20th arrondissement[31][32] was fire-bombed and its website hacked. The attacks were presumed to be linked to its decision to rename the edition of 3 November 2011 "Charia Hebdo", with Muhammad listed as the "editor-in-chief".[33] The cover, featuring a cartoon of Muhammad saying: "100 lashes of the whip if you don't die laughing" by Luz (Rénald Luzier), had circulated on social media for a couple of days.

The "Charia Hebdo" issue had been a response to recent news of the post-election introduction of sharia law in Libya and the victory of the Islamist party in Tunisia.[34] It especially focuses on oppression of women under sharia, taking aim at domestic violence, mandatory veiling, burquas, restrictions on freedom, forced marriage, and stoning of those accused of adultery. It also targeted oppression of gays and dissenters, and practices such as stoning, flogging, hand/foot/tongue amputations, polygamy, forced marriage, and early indoctrination of children. "Guest editor" Muhammad is portrayed as a good-humoured voice of reason, decrying the recent elections and calling for a separation between politics and religion, while stating that Islam is compatible with humour.[35][unreliable source?] The magazine responded to the bombing by distributing some four times the usual number of copies.[36]

Charb was quoted by Associated Press stating that the attack might have been carried out by "stupid people who don't know what Islam is" and that they are "idiots who betray their own religion". Mohammed Moussaoui, head of the French Council of the Muslim Faith, said his organisation deplores "the very mocking tone of the paper toward Islam and its prophet but reaffirms with force its total opposition to all acts and all forms of violence."[37] François Fillon, the prime minister, and Claude Guéant, the interior minister, voiced support for Charlie Hebdo,[32] as did feminist writer Ayaan Hirsi Ali, who criticised calls for self-censorship.[38]

2012 cartoons depicting Muhammad[]

In September 2012, the newspaper published a series of satirical cartoons of Muhammad.[39][40] One cartoon depicted Muhammad as a nude man on all fours with a star covering his anus.[41][42] Another shows Muhammad bending over naked and begging to be admired.[43] Given that this issue came days after a series of attacks on US embassies in the Middle East, purportedly in response to the anti-Islamic film Innocence of Muslims, the French government decided to increase security at certain French embassies, as well as to close the French embassies, consulates, cultural centres, and international schools in about 20 Muslim countries.[44] In addition, riot police surrounded the offices of the magazine to protect it against possible attacks.[40][45][46]

Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius criticised the magazine's decision, saying, "In France, there is a principle of freedom of expression, which should not be undermined. In the present context, given this absurd video that has been aired, strong emotions have been awakened in many Muslim countries. Is it really sensible or intelligent to pour oil on the fire?"[47] The US White House said "a French magazine published cartoons featuring a figure resembling the Prophet Muhammad, and obviously, we have questions about the judgment of publishing something like this."[48] When speaking before the United Nations later in the month, President Obama remarked more broadly that "The future must not belong to those who slander the prophet of Islam. But to be credible, those who condemn that slander must also condemn the hate we see in the images of Jesus Christ that are desecrated, or churches that are destroyed, or the Holocaust that is denied."[49] However, the newspaper's editor defended publication of the cartoons, saying, "We do caricatures of everyone, and above all every week, and when we do it with the Prophet, it's called provocation."[50][51]

2015 attack[]

On 7 January 2015, two Islamist gunmen[52] forced their way into the Paris headquarters of Charlie Hebdo and opened fire, killing twelve: staff cartoonists Charb, Cabu, Honoré, Tignous and Wolinski,[53] economist Bernard Maris, editors Elsa Cayat and Mustapha Ourrad, guest Michel Renaud, maintenance worker Frédéric Boisseau and police officers Brinsolaro and Merabet, and wounding eleven, four of them seriously.[54][55][56][57][58][59]

During the attack, the gunmen shouted "Allahu akbar" ("God is great" in Arabic) and also "the Prophet is avenged".[52][60] President François Hollande described it as a "terrorist attack of the most extreme barbarity".[61] The two gunmen were identified as Saïd Kouachi and Chérif Kouachi, French Muslim brothers of Algerian descent.[62][63][64][65][66]

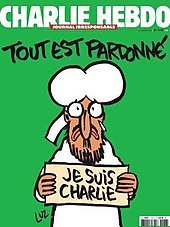

The "survivors' issue"[]

The day after the attack, the remaining staff of Charlie Hebdo announced that publication would continue, with the following week's edition of the newspaper to be published according to the usual schedule with a print run of one million copies, up significantly from its usual 60,000.[67][68] On 13 January 2015, the news came on BBC that the first issue after the massacre would come out in three million copies.[69] On Wednesday itself it was announced that with a huge demand in France, the print run would be raised from three to five million copies.[70] The newspaper announced the revenue from the issue would go towards the families of the victims.[71]

The French government granted nearly €1 million to support the magazine.[72] The (French: Fonds Google–AIPG pour l'Innovation Numérique de la presse), partially funded by Google, donated €250,000,[73] matching a donation by the French Press and Pluralism Fund.[74] The Guardian Media Group pledged a donation of £100,000.[75]

Je suis Charlie[]

After the attacks, the phrase Je suis Charlie, French for "I am Charlie", was adopted by supporters of Charlie Hebdo. Many journalists embraced the expression as a rallying cry for freedom of expression and freedom of the press.[77]

The slogan was first used on Twitter and spread to the Internet at large. The Twitter account and the original "Je suis Charlie" picture bearing the phrase in white Charlie Hebdo style font on black background were created by French journalist and artist just after the massacre.[78]

The website of Charlie Hebdo went offline shortly after the shooting, and when it returned it bore the legend Je Suis Charlie on a black background.[79] The statement was used as the hashtag #jesuischarlie on Twitter,[80] as computer-printed or hand-made placards and stickers, and displayed on mobile phones at vigils, and on many websites, particularly media sites. While other symbols were used, notably holding pens in the air, the phrase "Not Afraid", and tweeting certain images, "Je Suis Charlie" became more widespread.[81]

Republican marches[]

A series of rallies took place in cities across France on 10–11 January 2015 to honour the victims of the Charlie Hebdo shooting, and also to voice support for freedom of speech.[82]

Luz, one of the survivors of the attack, welcomed the show of support for the magazine, but criticized the use of symbols contrary to its values. He noted: "People sang La Marseillaise. We're speaking about the memory of Charb, Tignous, Cabu, Honoré, Wolinski: they would all have abhorred that kind of attitude."[83] Willem, another surviving cartoonist, declared support of free expression would be "naturally a good thing", but rejected that of far-right figures such as Geert Wilders and Marine Le Pen: "We vomit on those who suddenly declared that they were our friends".[84]

Other reactions[]

Unrest in Niger following the publication of the post-attack issue of Charlie Hebdo resulted in ten deaths,[85] dozens injured, and at least nine churches burned.[86] The Guardian reported seven churches burned in Niamey alone. Churches were also reported to be on fire in eastern Maradi and Goure. Violent demonstrations also were prevalent in Zinder, where some burned French flags. There were violent demonstrations in Karachi in Pakistan, where Asif Hassan, a photographer working for the Agence France-Presse, was seriously injured by a shot to the chest. In Algiers and Jordan, protesters clashed with police, while peaceful demonstrations were held in Khartoum, Sudan, Russia, Mali, Senegal, and Mauritania.[86]

Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov declared a regional holiday and denounced "people without spiritual and moral values" in front of an audience estimated to range between 600,000 and a million people in a demonstration in Grozny.[87]

One week after the murders, Donald Trump mocked Charlie Hebdo, saying the magazine reminded him of another "nasty and dishonest" satirical publication and that the magazine was on the verge of financial collapse.[88][89][90]

A British NGO, the Islamic Human Rights Commission, gave their 2015 international 'Islamophobe of the Year' award to Charlie Hebdo,[91] whereas another British organisation, the National Secular Society, awarded the Charlie Hebdo staff with Secularist of the Year 2015 "for their courageous response to the terror attack". The magazine said it would donate the associated £5,000 prize money to the fund that supports the families of the murdered cartoonists.[92]

Later controversies[]

Since January 2015 Charlie Hebdo has continued to be embroiled in controversy. Daniel Schneidermann argues that the 2015 attack raised the profile of the paper internationally with non-Francophone audiences, meaning that only parts of the paper are selectively translated into English, making it easy to misrepresent the editorial stance of the publication and the purpose of provocative work.[93]

In February 2015 Charlie Hebdo was accused of attacking freedom of press when its lawyer Richard Malka tried to prevent the publication of the magazine Charpie Hebdo, a pastiche of Charlie Hebdo.[94]

In October 2015 Nadine Morano was depicted as a baby with Down syndrome in the arms of General de Gaulle after making remarks supporting the National Front. This was criticized as a reference to de Gaulle's daughter, Anne, and as disparaging to people with disabilities. A response from a reader, a mother with a Down syndrome daughter, commented "The stupidity is racism, it's intolerance, it's Morano. The stupidity isn't trisomy [Down's syndrome]" (la bêtise, c'est le racisme, c'est l'intolérance, c'est Morano. La bêtise, ce n'est pas la trisomie)[95]

The 14 September 2015 edition's cover cartoon by Coco depicted a migrant being maltreated by a man who proclaims "welcome to refugees" – in order to parody European claims about compassion.[96] Riss wrote an editorial on the European migrant crisis, arguing that it was hypocritical for Hungarian politicians to declare themselves compassionate because of their Christian beliefs, but at the same time reject migrants from Syria. Riss parodied anti-immigrant attitudes by featuring a cartoon with a caricature of Jesus walking on water next to a drowning Muslim boy, with the caption "this is how we know Europe is Christian". The cartoons were widely seen as gallows humour in France, but prompted another wave of controversy abroad.[97] That issue also included a caricature of the dead body of Syrian Kurdish refugee child Alan Kurdi next to a McDonald's sign with the caption, "So close to the goal."[98] In response to criticism, cartoonist Corinne Rey said that she was criticising the consumerist society that was being sold to migrants like a dream.[99] After the New Year's Eve sexual assaults in Germany, a January 2016 edition included a cartoon by Riss about Kurdi, reflecting fickle sentiment towards refugees by including a caption questioning whether the boy would have grown up to be an "ass groper in Germany".[100][101][102][103]

Following the crash of Metrojet Flight 9268 in October 2015, which killed 224 civilians, mostly Russian women and children, and was seen by UK and US authorities as a probable terrorist bombing, Charlie Hebdo published cartoons which were perceived in Russia as mocking the victims of the tragedy.[104] One of the cartoons showed a victim's blue-eyed skull and a burned-out plane on the ground, with the caption: "The dangers of Russian low cost" flights.[105] The other showed pieces of the plane falling on an Islamic State (ISIS) fighter with the caption: "Russia's air force intensifies its bombing." A spokesman for Vladimir Putin called the artwork "sacrilege", and members of the State Duma called for the magazine to be banned as extremist literature and demanded an apology from France.[104]

In March 2016, one year after the attack, the weekly featured a caricature of Yahweh with a Kalashnikov rifle. The Vatican and Jewish groups said they were offended,[106][107] and the Associated Press censored images of the cover.[108][109]

In the same month, Charlie Hebdo published a front page following the 2016 Brussels bombings, in which the Belgian singer Stromae asks "Papa où t'es?" (Where are you dad?) and dismembered body parts reply "here". The cover upset the Belgian public and it particularly upset Stromae's family, because his father was murdered in the Rwandan genocide.[110][111][112]

On 2 September 2016, following the August 2016 Central Italy earthquake, which caused 294 deaths, the French magazine published a cartoon in which the earthquake victims are depicted as pasta dishes, under the title "Séisme à l'italienne".[113] In response to the reaction of Italians unleashed on social networks, the cartoonist Coco pointed out with another cartoon on the official Facebook page of the magazine, "Italians ... it's not Charlie Hebdo who builds your houses, it's the Mafia!"[114] The French ambassador in Rome, in a statement, pointed out that the French Government's position on the Italian earthquake is not that expressed by Charlie Hebdo.[115]

On 29 December 2016, Russia accused Charlie Hebdo of 'mocking' the Black Sea plane crash after publishing 'inhuman' cartoons about the disaster. In one reference to the crash, which claimed 92 lives, including 64 members of the Alexandrov Ensemble choir,[105] the French magazine depicted a jet hurtling downwards along with words translated as: 'Bad news ... Putin wasn't on board'. Russian defence spokesman called cartoons 'a poorly-created abomination'.[116] A Russian Defense Ministry spokesman said: "If such, I dare say, 'artistry' is the real manifestation of 'Western values', then those who hold and support them are doomed".[117]

2020 republication of Muhammad caricatures[]

On 1 September 2020, Charlie Hebdo announced that it will republish caricatures depicting Muhammad that sparked violent protests, ahead of a trial of suspected perpetrators of the mass shooting in January 2015 scheduled the following day.[118] Instagram suspended two accounts belonging to two of Charlie Hebdo's employees for several hours after they had published the caricatures of Muhammad. The accounts were reinstated after Instagram found they had been targeted by a reporting campaign by those who wished to censor the caricatures.[119]

2020 publication of Erdoğan cartoon[]

Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan condemned Charlie Hebdo after he found out that he was mocked in a front-page caricature. In the said cartoon, Erdogan was portrayed wearing his underwear, drinking alcohol, and lifting the skirt of a woman dressed in a hijab to reveal her buttocks.[120] Accompanying it was a caption that read, "Erdogan: He's very funny in private."[121] This came as tensions between Erdoğan and French president Emmanuel Macron rise over Macron's anti-Islamic comments, which were responded to by France recalling its ambassador to Ankara, as well as protests against France and calls for a boycott of French goods in several Muslim-majority countries,[122] including Turkey, where Erdoğan himself called for such a boycott. The tensions were, in turn, caused by the beheading of schoolteacher Samuel Paty in France after he showed caricatures of the prophet Muhammad, which were published by Charlie Hebdo, to his students as part of a lesson on free speech.[123]

While he admitted to have not yet seen the cartoon, Erdoğan called the images "despicable", "insulting", and "disgusting", and accused Charlie Hebdo of "cultural racism" and sowing "the seeds of hatred and animosity".[124] The Turkish government was also reported to take legal and diplomatic action. The state-run Anadolu Agency stated that the Ankara Chief Prosecutor's Office had already launched an investigation into the directors of Charlie Hebdo. On the other hand, Macron promised to defend the right to freedom of expression and freedom of publication.[125] Leaders of other Muslim-majority countries, such as Iranian supreme leader Ali Khamenei and Pakistani prime minister Imran Khan also criticised Macron and called for action against Islamophobia. On the contrary, Indian prime minister Narendra Modi and other European leaders, such as Danish foreign minister Jeppe Kofod, defended Macron.[126]

2020 attack[]

On 25 September 2020, weeks after the Muhammad caricature republications, two people were critically injured by an assailant during a stabbing attack outside the magazine's former headquarters. The building is now used by a television production company, and the two wounded victims were workers of the company. The perpetrator fled the scene but was arrested nearby. Six other people were arrested in connection to the attack.[128]

A day later, the perpetrator was identified as Zaheer Hassan Mehmood,[129] a 25-year-old allegedly from Pakistan, who claimed to have arrived as an unaccompanied minor refugee in France in 2018. He confessed to his actions and said he had acted in vengeance for the Muhammad caricature republications. He also reported that "he didn't know that the headquarters moved to another location".[130][131][132][133]

Interior minister of France Gérald Darmanin called the attack "fundamentally an act of Islamist terrorism".[134] Prime minister of France Jean Castex said "the enemies of the republic will not win" and pleged to escalate the fight against terrorism.[132] Emmanuel Macron faced backlash when he defended the caricatures. Many Muslims called for French products to be boycotted in their countries, while European leaders supported his remarks. Supermarkets in Kuwait and Qatar boycotted French goods.[135]

2021 publication of "Why I Left Buckingham Palace" cartoon[]

On 13 March 2021, Charlie Hebdo featured a controversial cartoon titled "Why I Left Buckingham Palace" on its front page.[136] The illustration depicted Queen Elizabeth II kneeling on the neck of Meghan, Duchess of Sussex, whose head was next to a quote bubble that read, "Because I couldn't breathe." It was published following Oprah Winfrey's interview of the Duchess and her partner, Prince Harry, Duke of Sussex, in which the couple accused the royal family of making racist hassles. The cartoon drew backlash from many social media users, as it satirically paralleled the incidents within the royal family with the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin.

Legal issues[]

Mosque of Paris v. Val (2007)[]

In 2007 the Grand Mosque of Paris began criminal proceedings against the chief-editor of Charlie Hebdo, Philipe Val, under France's hate speech laws for publicly abusing a group on the ground of their religion. The lawsuit was limited to three specific cartoons, including one depicting Muhammad carrying a bomb in his turban. In March 2007 a Paris court acquitted Val, finding that it was fundamentalists, rather than Muslims, who were being ridiculed in the cartoons.[137]

Siné sacking (2008)[]

On 2 July 2008, a column by the cartoonist Siné (Maurice Sinet) appeared in Charlie Hebdo citing a rumour that Jean Sarkozy, son of Nicolas Sarkozy, had announced his intention to convert to Judaism before marrying his fiancée, Jewish heiress Jessica Sebaoun-Darty. Siné added, "he'll go far, this lad!"[138] This led to complaints of antisemitism. The magazine's editor, Philippe Val, ordered Siné to write a letter of apology or face termination. The cartoonist said he would rather "cut his own balls off," and was promptly fired. Both sides subsequently filed lawsuits, and in December 2010, Siné won a €40,000 court judgment against his former publisher for wrongful termination.[139]

Amatrice v. Charlie Hebdo (2016)[]

In October 2016, the town council and municipality of Italian commune Amatrice –which was hit by an earthquake with hundreds dead– filed a lawsuit against Charlie Hebdo for "aggravated defamation", following publication of a series of cartoons titled 'Earthquake Italian style'. It depicted victims of the earthquake as Italian dishes and their blood as sauce.[140] The trial of this case opened on 9 October 2020 at the Paris court.[141]

Complaint in Turkey (2020)[]

In October 2020, prosecutors in the judicial system of Turkey began legal investigations into a criminal complaint filed by Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, whose lawyers argued that the cartoon depicting their client should be considered "libel" and was "not covered by freedom of expression".[142] In Turkey, insulting the president is punishable by four years in prison.[143]

Financial issues[]

Charlie Hebdo had struggled financially since its establishment until 2015. As the magazine was facing a loss of €100,000 by the end of 2014, it sought donations from readers to no avail.[144] The international attention to the magazine following the 2015 attack revived the publication, bringing some €4 million in donations from individuals, corporations and institutions, as well as a revenue of €15 million from subscriptions and newsstands between January and October 2015.[144] According to figures confirmed by the magazine, it gained more than €60 million in 2015, which declined to €19.4 million in 2016.[145] As of 2018 it spent €1–1.5 million annually for security services, according to Riss.[145]

Ownership[]

Since 2016, cartoonist Riss has been the publishing director of the magazine, and he owns 70% of the shares. The remaining 30% is owned by .[1] Following some controversies over the paper's future following the 2015 attack,[146] Charb's 40% stake in Charlie Hebdo was purchased from his parents by Riss and Eric Portheault, who were as of July 2015 sole shareholders in the paper. Charlie Hebdo switched to a new legal press publisher status which requires 70% of profits to be reinvested.[147] As of March 2011, Charlie Hebdo was owned by Charb (600 shares), Riss (599 shares), finance director Éric Portheault (299 shares), and Cabu and Bernard Maris with one share each.[148]

Staff[]

- Gérard Biard, editor

- Riss, cartoonist, managing editor, director of publication

- Catherine Meurisse, cartoonist

- Coco, cartoonist

- Willem, cartoonist

- , cartoonist

- Babouse, cartoonist

- , journalist

- Zineb El Rhazoui, journalist

- Philippe Lançon, critic

- Fabrice Nicolino, journalist

- Sigolène Vinson, journalist

- , journalist

- , critic

- Mathieu Madénian, columnist

- Simon Fieschi, webmaster

- Richard Malka, lawyer

- , finance manager

Accolades[]

On 5 May 2015, Charlie Hebdo was awarded the PEN/Toni and James C. Goodale Freedom of Expression Courage Award at the PEN American Center Literary Gala in New York City.[149] Granting the prize to Charlie Hebdo sparked vast controversy among writers[150] and 175 prominent authors boycotted the event due to "cultural intolerance" of the magazine.[151]

See also[]

- Le Canard enchaîné, a French satirical weekly newspaper

- Private Eye, a British satirical fortnightly magazine

- MAD Magazine, an American satirical bi-monthly magazine

References[]

- ^ a b Robert, Denis (8 January 2016). "L'histoire de Charlie Hebdo est shakespearienne" [The story of Charlie Hebdo is Shakespearian]. Télérama.

- ^ a b McNab 2006, p. 26: "Georges Bernier, the real name of 'Professor Choron', [... was] cofounder and director of the satirical magazine Hara Kiri, whose title was changed (to circumvent a ban, it seems!) to Charlie Hebdo in 1970."

- ^ Pineau, Elizabeth; Lowe, Christian (7 September 2020), Raissa Kasolowsky (ed.), "Charlie Hebdo uncowed after attacks - but now with bodyguards", Reuters, retrieved 30 September 2020,

Anticipating strong sales, the magazine said it printed 200,000 copies of last week’s issue. While before it struggled to stay afloat with weekly sales of 30,000, the first edition after the attacks sold 8 million copies. Weekly sales have now settled back to around 55,000, the magazine said.

- ^ "Charlie Hebdo: First cover since terror attack depicts prophet Muhammad". The Guardian. 13 January 2015. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ "2 vendors arrested for selling newspaper with Hebdo cartoon". Mid-Day.com. Mid-Day. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ Charb (Stéphane Charbonnier) (20 November 2013). "Non, "Charlie Hebdo" n'est pas raciste!" [No, Charlie Hebdo is not racist!]. Le Monde (in French). Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ Nuzzi, Olivia (14 January 2015). "The Charlie Hebdo conspiracy too crazy, even for Alex Jones". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ^ "Charlie Hebdo and its place in French journalism". BBC News. 8 January 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ^ "Charlie Hebdo: Gun attack on French magazine kills 12". BBC News. 7 January 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ^ "Charlie Hebdo: They're not racist just because you're offended". HuffPost. 13 January 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ^ Gibson, Megan. "The provocative history of French weekly newspaper Charlie Hebdo". Time. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ^ Withnall, Adam & Lichfield, John (7 January 2015). "Charlie Hebdo shooting: At least 12 killed as shots fired at satirical magazine's Paris office". The Independent. London, UK. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ^ a b Lemonnier 2008, p. 50

- ^ Sherwin, Adam (16 January 2015). "What is Charlie Hebdo? A magazine banned and resurrected but always in the grand tradition of Gallic satire". The Independent. Archived from the original on 16 January 2015. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ "Cavanna et 'les cons'". Le Monde. 14 February 2006. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ^ "Quelle est l'origine du nom Charlie Hebdo?". Lyon Capitale. 12 January 2015.

- ^ "Pourquoi Charlie Hebdo s'appelle Charlie Hebdo". Direct Matin. 8 January 2015.

- ^ "Wolinski L'ex-rédacteur en chef de "Charlie mensuel", se souvient de "Peanuts" "Ça serait bien de renouer avec ce genre de BD"". Libération. 14 February 2000.

- ^ Abbruzzese, Jason (7 January 2015). "What is Charlie Hebdo? Behind the covers of the French satirical magazine targeted in deadly attack". Mashable.com. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ^ Guiral, Antoine (12 September 1996). "Les 173704 signatures de Charlie Hebdo". Libération.

- ^ "L'opinion du patron". Les Mots Sont Importants. 4 March 2006.

- ^ Chabert, Chrystel. "Philippe Val : "Il ne faut pas que mes amis soient morts pour rien"". France Info. France TV Info. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ^ "Charlie Hebdo doit verser 90000 euros à Siné". Libération. 17 December 2012.

- ^ "Culte Musulman et Islam de France". CFCM TV. 22 March 2007. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ^ "Writers' statement on cartoons". BBC News. 1 March 2006. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ^ Heneghan, Tom (2 February 2007). "Cartoon row goes to French court". IOL. South Africa.

- ^ "Caricatures: Le soutien de Sarkozy à Charlie Hebdo fâche le CFCM". TF1 News. 15 December 2011. Archived from the original on 5 December 2011. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ^ "Charlie Hebdo: Sarkozy accusé de politiser le procès". L'Express. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ^ "French cartoons editor acquitted". BBC News. BBC. 22 March 2007.

- ^ "French satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo wins second trial over controversial cartoon ban request". NewsWireToday.com. Newswire.

- ^ Schofield, Hugh (3 November 2011). "Charlie Hebdo and its place in French journalism". BBC.

- ^ a b Boxel, James (2 November 2011). "Firebomb attack on satirical French magazine". Financial Times. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ^ "Attack on French satirical paper Charlie Hebdo". BBC. 2 November 2011. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ^ "Satirical French magazine names 'Muhammad' as editor". BBC News. 1 November 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ Gardiner, Bo (18 January 2015). "A closer look at 'Sharia Hebdo', for which Charlie Hebdo was firebombed in 2011" (blog).

- ^ "French paper reprints Mohammad cartoon after fire-bomb". Reuters. 3 November 2011. Archived from the original on 19 January 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ Ganley, Elaine (2 November 2011). "Fire at French newspaper after Muhammad issue". Boston Globe. Associated Press. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ^ Worthington, Peter (9 November 2011). "Extremists hurt non-militant Muslims the most". Toronto Sun. QMI.

- ^ "Charlie Hebdo publie des caricatures de Mahomet" (in French). BMFTV. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ^ a b Vinocur, Nicholas (19 September 2012). "Magazine's nude Mohammad cartoons prompt France to shut embassies, schools in 20 countries". National Post. Reuters. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ^ "What is Charlie Hebdo and why was it a target?/". The Globe and Mail.

When the anti-Islamic movie trailer "Innocence of Muslims" became a controversy, Charlie Hebdo's cartoons including one titled "Mohammed, a star is born!" It showed a bearded man on all fours, wearing nothing but a turban and a star covering his anus.

- ^ "Defend Charlie Hebdo's publishing disgusting cartoons about Muslims? Yes. Give them an award for it? No". The Nation.

... shows the Prophet naked on his hands and knees with his ass in the air, inviting anal sex; the cartoonist has drawn a star over his anus, and the caption says "a star is born". In a second cartoon, an ugly naked Mohammed figure in the same pose is asking the director filming him, "Do you like my ass?"

- ^ "The Charlie Hebdo affair: Laughing at blasphemy". The New Yorker.

Muhammad, labelled as such, is shown naked and bending over, begging to be admired. Then the Prophet is crouched on all fours, with genitals bared.

- ^ Samuel, Henry (19 September 2012). "France to close schools and embassies fearing Mohammed cartoon reaction". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- ^ Khazan, Olga (19 September 2012). "Charlie Hebdo cartoons spark debate over free speech and Islamophobia". The Washington Post (blog). Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ^ Keller, Greg; Hinnant, Lori (19 September 2012). "Charlie Hebdo Mohammed cartoons: France ups embassy security after prophet cartoons". HuffPost. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ^ Clark, Nicola (19 September 2012). "French magazine publishes cartoons mocking Muhammad". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ^ "Press briefing by press secretary Jay Carney". whitehouse.gov (Press release). Washington, DC. 19 September 2012 – via National Archives.

- ^ President Obama (25 September 2012). "Remarks by the President to the UN General Assembly". whitehouse.gov (speech). Retrieved 30 October 2020 – via National Archives.

- ^ "French leaders sound alarm over planned Mohammad cartoons". Reuters. 18 September 2012. Archived from the original on 19 September 2012. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ Stefan Simons (20 September 2012). "Charlie Hebdo editor in chief: 'A drawing has never killed anyone'". Der Spiegel.

- ^ a b Bremner, Charles (7 January 2015). "Islamists kill 12 in attack on French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo". The Times. London, UK.

- ^ "Attentat contre " Charlie Hebdo " : Charb, Cabu, Wolinski et les autres, assassinés dans leur rédaction". Le Monde (in French). 7 January 2015.

- ^ "Deadly attack on office of French magazine Charlie Hebdo". BBC News.

- ^ "Charlie Hebdo attack: What we know so far", BBC News, 8 January 2015.

- ^ "EN DIRECT. Massacre chez "Charlie Hebdo" : 12 morts, dont Charb et Cabu". Le Point.fr (in French). 7 January 2015.

- ^ "Les dessinateurs Charb et Cabu seraient morts". L'Essentiel (in French). France. 7 January 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ^ Conal Urquhart. "Paris Police Say 12 Dead After Shooting at Charlie Hebdo". Time.

Witnesses said that the gunmen had called out the names of individual from the magazine. French media report that Charb, the Charlie Hebdo cartoonist who was on al-Qaeda's most wanted list in 2013, was seriously injured.

- ^ Victoria Ward. "Murdered Charlie Hebdo cartoonist was on al Qaeda wanted list". The Telegraph.

- ^ "The Globe in Paris: Police identify three suspects". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ Adam Withnall, John Lichfield, "Charlie Hebdo shooting: At least 12 killed as shots fired at satirical magazine's Paris office", The Independent, 7 January 2015.

- ^ Higgins, Andrew; de la Baume, Maïa (8 January 2015). "Two Brothers Suspected in Killings Were Known to French Intelligence Services". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ^ "Paris shooting: Female police officer dead following assault rifle attack morning after Charlie Hebdo killings". The Independent. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ "Un commando organisé". Libération. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ^ "Paris Attack Suspect Dead, Two in Custody, U.S. Officials Say". NBC News. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ^ "France, Islam, terrorism and the challenges of integration: Research roundup". Archived from the original on 26 October 2015. Retrieved 23 January 2015. JournalistsResource.org. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- ^ "Charlie Hebdo will come out next week, despite bloodbath". The Times of India. 8 January 2015.

- ^ "Charlie Hebdo Attack: Magazine to publish next week". BBC News. 8 January 2015. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ "Defiant Charlie Hebdo depicts Prophet Muhammad on cover". BBC News. 13 January 2015. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ "Charlie Hebdo Attack: Magazine to publish next week". BBC News. 8 January 2015. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ "Charlie Hebdo attack: Print run for new issue expanded". BBC News. 14 January 2015. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ "Charlie Hebdo: Pellerin veut débloquer un million d'euros". Le Figaro (in French). 8 January 2015. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ Brandom, Russell (8 January 2015). "Charlie Hebdo will publish one million copies next week". The Verge.

- ^ Jon Stone (8 January 2015). "French media raises €500,000 to keep satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo open". The Independent.

- ^ McPhate, Mike; MacKey, Robert (8 January 2015). "Updates on the 2nd day of search for suspects in Charlie Hebdo shooting". The New York Times.

- ^ "How I created the Charlie Hebdo magazine cover: cartoonist Luz's statement in full". The Daily Telegraph. 13 January 2015. Archived from the original on 13 January 2015.

- ^ ""Je suis Charlie" image". Enis Yavuz. Archived from the original on 9 January 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ^ "#JeSuisCharlie creator: Phrase cannot be a trademark". BBC News. 14 January 2015. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ^ "Charlie Hedbo". 7 January 2015. Archived from the original on 7 January 2015.

- ^ Booth, Richard (7 January 2015). "'Je suis Charlie' trends as people refuse to be silenced by Charlie Hebdo gunmen". Daily Mirror.

- ^ Hanne, Isabelle. "Charlies' installe à "Libé" : Bon, on fait le journal?". Libération (in French). Archived from the original on 15 August 2015. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ "Paris terror suspects killed in twin French police raids". Bloomberg. 9 January 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ^ "Luz: le soutien à Charlie Hebdo est à "contre-sens" de ses dessins". Le Point – via Le Point.fr.

- ^ "Willem : "Nous vomissons sur ceux qui, subitement, disent être nos amis"". Le Point – via Le Point.fr.

- ^ "Five killed in second day of Charlie Hebdo protests in Niger". Reuters. 17 January 2015. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ^ a b Graham-Harrison, Emma (17 January 2015). "Niger rioters torch churches and attack French firms in Charlie Hebdo protest". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ^ Davidzon, Vladislav (23 January 2015). "Why Russia is no place to be Charlie". Tablet. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^ "Twitter". mobile.twitter.com. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ "Twitter". mobile.twitter.com. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ "Donald Trump's mocking tweets about Charlie Hebdo resurface after President criticises terrorism coverage". The Independent. London, UK. 8 February 2017.

- ^ Richards, Victoria (11 March 2015). "Charlie Hebdo: Murdered staff given 'Islamophobe of the Year' award". The Independent. London, UK. Archived from the original on 12 March 2015. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ^ "Charlie Hebdo staff awarded Secularist of the Year prize for their response to Paris attacks" (Press release). NSS. 28 March 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- ^ "Charlie Hebdo de nouveau victime de son paradoxal succès". Slate (in French). 14 January 2016.

- ^ "Quand 'Charlie Hebdo' veut faire interdire "Charpie Hebdo"". France TV info. 18 February 2015.

- ^ Lambert, Elise. ""Charlie Hebdo" : "On se moque de Nadine Morano, pas des handicapés", explique la dessinatrice Coco". France TV info.

- ^ "Charlie Hebdo mocks Europe's response to migrant crisis with cartoons of dead Syrian boy". The New York Times. 16 September 2015.

- ^ "Les dessins de 'Charlie Hebdo' sur la mort du petit Aylan scandalisent les internautes à l'étranger". Le Huffington Post (in French). 15 September 2015.

- ^ "Charlie Hebdo cartoon depicts drowned toddler Aylan Kurdi as future sexual harasser". Newsweek. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ^ MacKey, Robert (15 September 2015). "Charlie Hebdo mocks Europe's response to migrant crisis with cartoons of dead Syrian boy". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ^ Brown, Jessica (14 January 2016). "The Charlie Hebdo cartoon about Aylan Kurdi and sex attackers is one of its most powerful". The Independent.

- ^ "Charlie Hebdo cartoon depicts grown-up Aylan Kurdi as 'ass groper in Germany'". The Independent. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ^ "Charlie Hebdo cartoon depicting drowned child Alan Kurdi sparks racism debate". The Guardian. 14 January 2016. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ^ "Charlie Hebdo backlash over 'racist' Alan Kurdi cartoon". BBC News. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ^ a b "Russia hits out at Charlie Hebdo over crash cartoon". BBC News. 6 November 2015. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- ^ a b "French Satirists at Charlie Hebdo infuriate Russians with mockery of 25 Dec. plane crash". The Moscow Times. 28 December 2016.

- ^ "Vatican newspaper denounces 'woeful' Charlie Hebdo cover". Yahoo News. 6 January 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ "Chief Rabbi Ephraim Mirvis says Charlie Hebdo 'God' cartoon is insulting to believers". The Jewish Chronicle. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ Wemple, Erik (7 January 2016). "AP removes images of God-as-terrorist Charlie Hebdo cover". The Washington Post. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ "Associated Press self-censors anniversary Charlie Hebdo cover". Reason. 7 January 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ ""Papa où t'es ?" : la famille de Stromae et les Belges répondent à Charlie-Hebdo". La Depeche (in French). 31 March 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ ""Papa où t'es ?" Le dessin en "une" de "Charlie Hebdo" blesse la Belgique". Le Monde (in French). 30 March 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ ""Charlie Hebdo": La une qui choque les proches de Stromae". 20 minutes (in French). 31 March 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ "Charlie Hebdo draws Italian anger with cartoon portraying earthquake victims as pasta". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ^ Coco (cartoonist). "The drawing of the day, by coco". Charlie Hebdo. Retrieved 2 March 2019 – via Facebook.[non-primary source needed]

- ^ "French embassy disowns Charlie Hebdo cartoons". ANSA. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ^ "Russian military irked by Charlie Hebdo cartoons mocking plane crash". CTVNews. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- ^ "Charlie Hebdo cover: Russia angered by cartoon of TU-154 plane crash". International Business Times. 28 December 2016.

- ^ "Charlie Hebdo republishes cartoons depicting prophet Mohammed". The Brussels Times. 1 September 2020.

- ^ Sautreuil, Pierre (6 September 2020). "Instagram suspend brièvement les comptes de journalistes de "Charlie Hebdo" ayant publié des caricatures de Mahomet". Le Figaro (in French). Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ "Turkey threatens legal action over Charlie Hebdo's caricature of president". The Guardian. 28 October 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ "Erdogan slams 'scoundrels' over Charlie Hebdo cartoon". DW News. 28 October 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ "Anger towards Emmanuel Macron grows in Muslim world". The Guardian. 28 October 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ "France, Turkey And The Charlie Hebdo Cartoons: What's Behind The Dispute?". NPR. 28 October 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ "Charlie Hebdo sparks fury with cartoon of Turkey's President Erdogan in underpants". South China Morning Post. Agence France-Presse. 28 October 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ "Turkish leaders condemn Charlie Hebdo magazine over cartoon mocking Erdogan". Global News. 28 October 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ "Erdogan vows action over Charlie Hebdo Cartoon". The Jakarta Post. 28 October 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ "At least 50,000 stage anti-France rally in Bangladesh". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ^ "Charlie Hebdo: Stabbing attacks leave two wounded near magazine's former offices in Paris". Sky News. 25 September 2020.

- ^ "Attaque devant les ex-locaux de " Charlie " : le suspect mis en examen pour " tentatives d'assassinats " terroristes". Le Monde (in French). Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ "Il "assume" son acte : qui est Ali H., l'auteur présumé de l'attaque à Paris?".

- ^ Abrahamsson, Samuel; Nordlund, Felicia (25 September 2020). "Flera gripna efter knivattacken i Paris". SVT Nyheter (in Swedish). Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ a b "Chief suspect in Paris stabbing was angered by Charlie Hebdo cartoons". The Irish Times. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ "Attaque à Paris : l'assaillant a reconnu être âgé de 25 ans et non 18". Le Figaro.fr (in French). 29 September 2020. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ "Attaque à Paris: "manifestement c'est un acte de terrorisme islamiste" pour Gérald Darmanin" (in French). BFMTV. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ Mostafa Salem, Pierre Bairin, Chris Liakos, Nadine Schmidt and Sarah Dean. "Calls to boycott French products grow in Muslim world after Macron backs Mohammed cartoons". CNN.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ "Magazine cover showing Queen Elizabeth II kneeling on Meghan's neck sparks outrage". NBC News. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ Janssen, Esther (8 March 2012) [2009]. "Limits to expression on religion in France". Journal of European Studies. Agama & Religiusitas di Eropa. V (1): 22–45.

Produced in cooperation between the University of Indonesia and the Delegation of the European Commission

; Research Paper No. 2012–45 (Report). Amsterdam Law School.; Paper No. 2012–39 (Report). Institute for Information Law Research – via SSRN. - ^ Leprince, Chloé. "L'Affaire Siné 2008-09-17". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ "Le Tribunal de Grande Instance donne raison à Siné contre Charlie Hebdo". ActuaBD. 11 December 2010.

- ^ "No longer Charlie: Amatrice to sue Charlie Hebdo over cartoon", Euronews, 12 October 2016

- ^ Lemaignen, Julien (9 October 2020), "A l'autre procès " Charlie Hebdo " : " Cette plainte, c'est open-bar "", Le Monde (in French)

- ^ Cupolo, Diego (28 October 2020), "Erdogan sues Charlie Hebdo over caricature", Al-Monitor

- ^ "Turkish leaders condemn "immoral" Charlie Hebdo cartoon mocking Erdogan". www.cbsnews.com. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ a b Clark, Nicola (24 October 2015), "Charlie Hebdo's Recovery From Attacks Opens New Wounds for Staff", The New York Times

- ^ a b "Paris commemorates victims of Charlie Hebdo, Hyper Cacher attacks", France24, 7 January 2018

- ^ Picquard, Alexandre (18 May 2015). "La vie à "Charlie" n'a jamais été un fleuve tranquille". Le Monde. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ^ "Charlie Hebdo devient la première 'entreprise solidaire de presse'". Le Monde. 17 July 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ^ "Cabu reste actionnaire de Charlie Hebdo". Charlie Enchaîné. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ^ Susman, Tina (5 May 2015). "At PEN Gala, Charlie Hebdo editor calls for free expression and debate". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ "PEN gala honours Charlie Hebdo despite uproar". France24. 6 May 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ "Charlie Hebdo slammed as 'hypocrites' over staff dispute". France24. 15 May 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

Further reading[]

- Egen, Jean (1976). La Bande à Charlie. Stock. ISBN 9782234005532.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charlie Hebdo. |

- Official website: charliehebdo.fr (in French)

- "Un historique d'Hara-Kiri / Charlie Hebdo". uqac.uquebec.ca (in French). Quebec, Canada: L'Université du Québec. Archived from the original on 24 March 2007.

- Charlie Hebdo

- 1970 establishments in France

- Anti-clericalism

- Critics of religions

- Satirical magazines published in France

- Comics magazines published in France

- Weekly magazines published in France

- French-language magazines

- Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy

- Magazines established in 1960

- Magazines published in Paris

- Obscenity controversies in literature

- Obscenity controversies in comics

- Religious parodies and satires

- Far-left politics in France

- Atheism in France

- French sceptics

- Comics critical of religion

- Comics controversies

- Religious controversies in literature

- Religious controversies in comics

- Controversies in France

- French political satire

- Satirical comics