The Message (1976 film)

| The Message | |

|---|---|

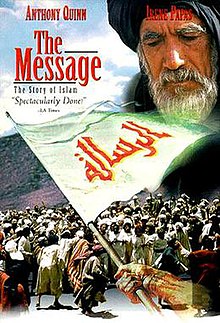

DVD poster | |

| Directed by | Moustapha Akkad |

| Written by |

|

| Based on | Prophet Muhammad |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Narrated by | Richard Johnson |

| Cinematography | Jack Hildyard |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | Maurice Jarre |

Production company | Filmco International Productions Inc. |

| Distributed by | Tarik Film Distributors |

Release date | |

Running time |

|

| Countries | |

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $10 million |

| Box office | $15 million |

The Message (Arabic: الرسالة Ar-Risālah means Prophecy; originally known as Mohammad, Messenger of God) is a 1976 Islamic epic drama film directed and produced by Moustapha Akkad, chronicling the life and times of the Islamic prophet Muhammad through the perspective of his uncle Hamza ibn Abdul-Muttalib and adopted son Zayd ibn Harithah.

Released in both separately-filmed Arabic and English-language versions, The Message serves as an introduction to early Islamic history. The international ensemble cast includes Anthony Quinn, Irene Papas, Michael Ansara, Johnny Sekka, Michael Forest, André Morell, Garrick Hagon, Damien Thomas, and Martin Benson. It was an international co-production between Libya, Morocco, Lebanon, Syria and the United Kingdom.

The film was nominated for Best Original Score in the 50th Academy Awards, composed by Maurice Jarre, but lost the award to Star Wars (composed by John Williams).

Plot[]

The film begins with Muhammad sending an invitation to accept Islam to surrounding rulers: Heraclius, the Byzantine Emperor; the Patriarch of Alexandria; the Sasanian Emperor.

Earlier Muhammad is visited by the angel Gabriel, which shocks him deeply. The angel asks him to start and spread Islam. Gradually, almost the entire city of Mecca begins to convert. As a result, more enemies will come and hunt Muhammad and his companions from Mecca and confiscate their possessions. Some of these followers fled to Abyssinia to seek refuge with the protection given by the king there.

They head north, where they receive a warm welcome in the city of Medina and build the first Islamic mosque. They are told that their possessions are being sold in Mecca on the market. Muhammad chooses peace for a moment, but still gets permission to attack. They are attacked but win the Battle of Badr. The Meccans want revenge and beat back with three thousand men in the Battle of Uhud, killing Hamza. The Muslims run after the Meccans and leave the camp unprotected. Because of this, they are surprised by riders from behind, so they lose the battle. The Meccans and the Muslims close a 10-year truce.

A few years later, Khalid ibn Walid, a Meccan general who has killed many Muslims, converts to Islam. Meanwhile, Muslim camps in the desert are attacked in the night. The Muslims believe that the Meccans are responsible. Abu Sufyan comes to Medina fearing retribution and claiming that it was not the Meccans, but robbers who had broken the truce. None of the Muslims give him an audience, claiming he "observes no treaty and keeps no pledge." The Muslims respond with an attack on Mecca with very many troops and "men from every tribe".

Abu Sufyan seeks an audience with Muhammad on the eve of the attack. The Meccans become very scared but are reassured that people in their houses, by the Kaaba, or in Abu Sufyan's house will be safe. They surrender and Mecca falls into the hands of the Muslims without bloodshed. The pagan images of the gods in the Kaaba are destroyed, and the very first azan in Mecca is called on the Kaaba by Bilal ibn Rabah. The Farewell Sermon is also delivered.

Cast[]

- English version

- Anthony Quinn as Hamza

- Irene Papas as Hind bint Utbah

- Michael Ansara as Abu Sufyan ibn Harb

- Johnny Sekka as Bilal ibn Rabah

- Michael Forest as Khalid ibn al-Walid

- André Morell as Abu Talib

- Garrick Hagon as Ammar ibn Yasir

- Damien Thomas as Zayd

- Martin Benson as Abu Jahl

- Robert Brown as Utbah ibn Rabi'ah

- Rosalie Crutchley as Sumayyah

- Bruno Barnabe as Umayyah ibn Khalaf

- Neville Jason as Ja`far ibn Abī Tālib

- John Bennett as Salul

- Donald Burton as 'Amr ibn al-'As

- Earl Cameron as Al-Najashi

- as Walid ibn Utbah

- Nicholas Amer as Suhayl ibn Amr

- as Mus`ab ibn `Umair

- as Baraa'

- as Ubaydah

- Ewen Solon as Yasir

- Wolfe Morris as Abu Lahab

- Ronald Leigh-Hunt as Heraclius

- Leonard Trolley as Silk Merchant

- as Poet Sinan

- as Hudhayfah

- Peter Madden as Toothless Man

- Hassan Joundi as Khosrau II

- as Ikrimah

- Elaine Ives-Cameron as Arwa

- as Money Lender

- as Young Christian

Arabic version

- Abdullah Gaith as Hamza

- Muna Wassef as Hind

- as Abu Sufyan ibn Harb

- Ali Ahmed Salem as Bilal

- Mahmoud Said as Khalid

- Ahmad Marey as Zayd

- Mohammad Larbi as Ammar

- Hassan Joundi as Abu Jahl

- as Sumayyah

- Martin Benson as Khosrau II

- Damien Thomas as Young Christian

Production[]

While creating The Message, director Akkad, who was Muslim, consulted Islamic clerics in a thorough attempt to be respectful towards Islam and its views on portraying Muhammad. He received approval from Al-Azhar in Egypt but was rejected by the Muslim World League in Mecca, Saudi Arabia.[citation needed]

Financing for the project initially came from the Libyan leader Moammar Gaddafi, Kuwait and Morocco, but when it was rejected by the Muslim World League, Emir Sabah III Al-Salim Al-Sabah of Kuwait withdrew financial support.[citation needed] King Hassan II of Morocco gave Akkad full support for the production while then-Libyan leader Muammar al-Gaddafi provided the majority of the financial support too.[4]

The film was shot in Morocco and Libya, with production taking four and a half months to build the sets for Mecca and Medina as imagined in Muhammad's time. Production took one year; Akkad filmed for six months in Morocco but had to stop when the Saudi government exerted great pressure on the Moroccan government to stop the project. Akkad went to al-Gaddafi for support in order to complete the project, and the Libyan leader allowed him to move the filming to Libya for the remaining six months.[citation needed]

Akkad saw the film as a way to bridge the gap between the Western and Islamic worlds, stating in a 1976 interview:

I did the film because it is a personal thing for me. Besides its production values as a film, it has its story, its intrigue, its drama. Besides all this I think there was something personal, being a Muslim myself who lived in the west I felt that it was my obligation my duty to tell the truth about Islam. It is a religion that has a 700 million following, yet it's so little known about which surprised me. I thought I should tell the story that will bring this bridge, this gap to the west.[citation needed]

Akkad also filmed an Arabic version of the film simultaneously with an Arab cast, for Arabic-speaking audiences. He felt that dubbing the English version into Arabic would not be enough, because the Arabic acting style differs significantly from that of Hollywood. The actors took turns doing the English and Arabic versions in each scene.[citation needed]

Depiction of Muhammad[]

In accordance with the beliefs of some Muslims regarding depictions of Muhammad, his face is not depicted on-screen nor is his voice heard. Because Islamic tradition generally forbids any direct representation of religious figures, the following disclaimer is displayed at the beginning of the film:

The makers of this film honour the Islamic tradition which holds that the impersonation of the Prophet offends against the spirituality of his message. Therefore, the person of Mohammad will not be shown (or heard).

The rule above was also extended to his wives, his daughters including Fatimah, Zainab, Umm Kulthum, Ruqayyah, his sons-in-law, and the first caliphs (Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, and Ali ibn Talib his paternal cousin). This left Muhammad's uncle Hamza (Anthony Quinn) and his adopted son Zayd (Damien Thomas) as the central characters. During the battles of Badr and Uhud depicted in the movie, Hamza was in nominal command, even though the actual fighting was led by Muhammad, Hamza and Ali.

Whenever Muhammad was present or very close by, his presence was indicated by light organ music. His words, as he spoke them, were repeated by someone else such as Hamza, Zayd or Bilal. When a scene called for him to be present, the action was filmed from his point of view. Others in the scene nodded to the unheard dialogue or moved with the camera as though moving with Muhammad.

The closest the film comes to a depiction of Muhammad or his immediate family are the view of Ali's famous two-pronged sword Zulfiqar during the battle scenes, a glimpse of a staff in the scenes at the Kaaba or in Medina, and Muhammad's camel, Qaswa.

Reception[]

In July 1976, five days before the film opened in London's West End, threatening phone calls to a cinema prompted Akkad to change the title from Mohammed, Messenger of God to The Message, at a cost of £50,000.[5]

Sunday Times film critic Dilys Powell described the film as a "Western … crossed with Early Christian". She noted a similar avoidance of direct depictions of Jesus in early biblical films, and suggested that "from an artistic as well as a religious point of view the film is absolutely right".[6] Richard Eder of The New York Times described the effect of not showing Muhammad as "awkward" and likened it to "one of those Music Minus One records," adding that the acting was "on the level of crudity of an early Cecil B. DeMille Bible epic, but the direction and pace is far more languid."[7] Variety praised the "stunning" photography, "superbly rendered" battle scenes and the "strong and convincing" cast, though the second half of the film was called "facile stuff and anticlimactic."[8] Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times thought the battle scenes were "spectacularly done" and that Anthony Quinn's "dignity and stature" were right for his role.[9] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave it two stars out of four, calling it "a decent, big-budget religious movie. No more, no less."[10] John Pym of The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote: "The unalleviated tedium of this ten-million dollar enterprise (billed as the first 'petrodollar' movie) is largely due to the tawdry staginess of all the sets and the apparent inability of Moustapha Akkad ... to muster larger groups of people on any but two-dimensional planes."[11]

In 1977, as the film was scheduled to premiere in the United States, a splinter group of the black nationalist Nation of Islam calling itself the Hanafi Movement staged a siege of the Washington, D.C. chapter of the B'nai B'rith.[12] Under the mistaken belief that Anthony Quinn played Muhammad in the film,[13] the group threatened to blow up the building and its inhabitants unless the film's opening was cancelled.[12][13] The standoff was resolved after the deaths of a journalist and a policeman,[citation needed] but "the film's American box office prospects never recovered from the unfortunate controversy."[13]

Muna Wassef's role as Hind in the Arabic-language version won her international recognition.[14]

Awards and nominations[]

The film was nominated for an Oscar in 1977 for Best Original Score for the music by Maurice Jarre.[15]

Music[]

The musical score of The Message was composed and conducted by Maurice Jarre and performed by the London Symphony Orchestra.

- Track listing for the first release on LP

Side One

- The Message (3:01)

- Hegira (4:24)

- Building the First Mosque (2:51)

- The Sura (3:34)

- Presence of Mohammad (2:13)

- Entry to Mecca (3:15)

Side Two

- The Declaration (2:38)

- The First Martyrs (2:27)

- Fight (4:12)

- Spread of Islam (3:16)

- Broken Idols (4:00)

- The Faith of Islam (2:37)

- Track listing for the first release on CD

- The Message (3:09)

- Hegira (4:39)

- Building the First Mosque (2:33)

- The Sura (3:32)

- Presence of Mohammad (2:11)

- Entry to Mecca (3:14)

- The Declaration (2:39)

- The First Martyrs (2:26)

- Fight (4:11)

- The Spread of Islam (3:35)

- Broken Idols (3:40)

- The Faith of Islam (2:33)

Potential remake[]

In October 2008, producer Oscar Zoghbi revealed plans to "revamp the 1976 movie and give it a modern twist," according to IMDb and the World Entertainment News Network.[16][17][18][19] He hoped to shoot the remake, tentatively titled The Messenger of Peace, in the cities of Mecca and Medina in Saudi Arabia.

In February 2009, Barrie M. Osborne, producer of The Matrix and The Lord of the Rings film trilogies, was attached to produce a new film about Muhammad. The film was to be financed by a Qatari media company and was to be supervised by Sheikh Yusuf al-Qaradawi.[20]

See also[]

- List of Islamic films

- Battle of Badr

- Battle of Uhud

- List of films about Muhammad

References[]

- ^ "'Mohammad' Preems In London, July 29". Variety: 5. 7 July 1976.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Coeli; Walker, Adam Hani, eds. (2014). Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Prophet of God. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, LLC. p. 98. ISBN 9781610691789.

- ^ "THE MESSAGE [ARABIC VERSION] (A)". British Board of Film Classification. 20 August 1976. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ حقيقة الفيلم الذي اسلم من بعده الاجانب وحاربه ال سعود on YouTube published September 20, 2012

- ^ "Muhammad film title changed after threats." The Times (London, 27 July 1976), 4.

- ^ Dilys Powell, "In pursuit of the Prophet", Sunday Times (London, 1 August 1976), p. 29.

- ^ Eder, Richard (10 March 1977). "Screen: 3-Hour 'Mohammad'". The New York Times: 28.

- ^ "The Message". Variety: 22. 18 August 1976.

- ^ Champlin, Charles (March 8, 1977). "Islam as It Lives and Bleeds". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 1.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (March 29, 1977). "Protests aside, 'Mohammad' is a faithful, big-budget epic". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 10.

- ^ Pym, John (September 1976). "Al-Risalah (The Message [Mohammad Messenger of God])". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 43 (512): 187.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brockopp, Jonathan E (19 April 2010). The Cambridge Companion to Muhammad. Cambridge University Press. p. 287.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Deming, Mark. "Mohammad: Messenger of God". New York Times. Archived from the original on 21 May 2008. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ^ Samir Twair and Pat Twair, "Syrian stars receive first Al-Ataa awards", The Middle East (1 December 1999).

- ^ "1977 Oscars - 50th Annual Academy Awards Oscar Winners and Nominees". Popculturemadness.com. 3 April 1978. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ "The Message Gets A Modern Remake," IMDB, 28 October 2008.

- ^ Irvine, Chris (28 October 2008). "Prophet Mohammed film The Message set for remake". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 1 November 2008. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ Brooks, Xan (27 October 2008). "Controversial biopic of Muhammad set for remake". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ "Prophet Muhammad film announced". BBC News. 28 October 2008. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ "'Matrix' And 'Lord of the Rings' Producer To Make Movie About The Founder Of Islam". Moviesblog.mtv.com. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mohammad, Messenger of God. |

- 1976 films

- 1970s biographical drama films

- 1970s adventure drama films

- 1970s historical adventure films

- 1970s war drama films

- Adventure films based on actual events

- Arabic-language films

- British films

- British biographical drama films

- British epic films

- British historical adventure films

- British war drama films

- Drama films based on actual events

- English-language films

- Epic films based on actual events

- Films scored by Maurice Jarre

- Films about Muhammad

- Films about Islam

- Films directed by Moustapha Akkad

- Films set in the 7th century

- Films set in deserts

- Films shot from the first-person perspective

- Films shot in Libya

- Films shot in Morocco

- Islam-related controversies

- Kuwaiti films

- Lebanese films

- Libyan films

- Moroccan drama films

- Moroccan films

- Religious adventure films

- Religious epic films

- War epic films

- War films based on actual events

- Historical epic films

- 1970s multilingual films

- British multilingual films

- 1976 directorial debut films

- 1976 drama films

- 1970s in Islam