Cinnamomum cassia

| Cinnamomum cassia | |

|---|---|

| |

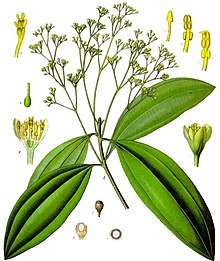

| From Koehler's Medicinal-Plants (1887) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Magnoliids |

| Order: | Laurales |

| Family: | Lauraceae |

| Genus: | Cinnamomum |

| Species: | C. cassia

|

| Binomial name | |

| Cinnamomum cassia (L.) J.Presl

| |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Cinnamomum cassia, called Chinese cassia or Chinese cinnamon, is an evergreen tree originating in southern China, and widely cultivated there and elsewhere in South and Southeast Asia (India, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam).[2] It is one of several species of Cinnamomum used primarily for their aromatic bark, which is used as a spice. The buds are also used as a spice, especially in India, and were once used by the ancient Romans.

The tree grows to 10–15 m (33–49 ft) tall, with greyish bark and hard, elongated leaves that are 10–15 cm (3.9–5.9 in) long and have a decidedly reddish colour when young.

Origin and types[]

Chinese cassia is a close relative to Ceylon cinnamon (C. verum), Saigon cinnamon (C. loureiroi), also known as "Vietnamese cinnamon", Indonesian cinnamon (C. burmannii), also called "korintje", and Malabar cinnamon (C. citriodorum) from Malabar region in India. In all five species, the dried bark is used as a spice. Chinese cassia's flavour is less delicate than that of Ceylon cinnamon. Its bark is thicker, more difficult to crush, and has a rougher texture than that of Ceylon cinnamon.[3]

Most of the spice sold as cinnamon in the United States, United Kingdom, and India is Chinese cinnamon.[3][unreliable source?] "Indonesian cinnamon" (C. burmannii) is sold in much smaller amounts.[citation needed]

Chinese cassia is produced in both China and Vietnam. Until the 1960s, Vietnam was the world's most important producer of Saigon cinnamon, which has a higher oil content[citation needed], and consequently has a stronger flavor. Because of the disruption caused by the Vietnam War, however, production of Indonesian cassia in the highlands of the Indonesia island of Sumatra was increased to meet demand.[citation needed] Indonesian cassia has the lowest oil content of the three types of cassia, so commands the lowest price. Chinese cassia has a sweeter flavor than Indonesian cassia, similar to Saigon cinnamon, but with lower oil content.[citation needed]

Cassia bark[]

Cassia bark (both powdered and in whole, or "stick" form) is used as a flavoring agent for confectionery, desserts, pastries, and meat; it is specified in many curry recipes, where Ceylon cinnamon is less suitable. Cassia is sometimes added to Ceylon cinnamon, but is a much thicker, coarser product. Cassia is sold as pieces of bark (as pictured below) or as neat quills or sticks. Cassia sticks can be distinguished from Ceylon cinnamon sticks in this manner: Ceylon cinnamon sticks have many thin layers and can easily be made into powder using a coffee or spice grinder, whereas cassia sticks are extremely hard and are usually made up of one thick layer.[citation needed]

Cassia buds[]

Cassia buds, although rare, are also occasionally used as a spice. They resemble cloves in appearance and have a mild, flowery cinnamon flavor. Cassia buds are primarily used in old-fashioned pickling recipes, marinades, and teas.[4]

Traditional Chinese medicine uses and implications[]

Cinnamomum cassia is known for its sweet flavor and can be used as a spice for food, or for its aroma. In vitro, it has shown potential for anti microbial activity. [5][6] Some followers of traditional medicine believe that C. cassia is associated with the Earth element, and due it's sweet flavors they associate it with the color yellow.[7][dubious ] This has no basis in science, and neither the plant nor the spice is actually yellow. Traditional Chinese Medicine associates the Earth element with the spleen organ associated with Yin, and the stomach organ associated with Yang.[dubious ].[7] Cinnamon can be useful (according to traditional Chinese medicine) when treating patients with deficiency of Qi in the stomach or spleen organs and symptoms from these organs can include diarrhea, lack of energy, and shortness of breath.[dubious ] [5][7] Modern medicine however shows us that these ideas are dangerous and misfounded, potentially causing people to forgo treatment, and lack any concrete basis in science or reality. Traditional Chinese medicine practicers believe that through the consumption of this Earth element, patients can replenish their deficiency of Qi and they also believe physicians can do so by observing the facial color of patients and associating the disorder with its color.[5][7][dubious ]

Health effects[]

Chinese cassia (called ròuguì; 肉桂 in Chinese) is produced primarily in the southern provinces of Guangxi, Guangdong, and Yunnan. It is considered one of the 50 fundamental herbs in traditional Chinese medicine.[8] More than 160 chemicals have been isolated from Cinnamomum cassia.[9]

Due to a blood-thinning component called coumarin that could damage the liver if consumed in larger amounts,[10] European health agencies have warned against consuming high amounts of cassia.[11] Other bioactive compounds found in the bark, powder and essential oils of C. cassia are cinnamaldehyde and styrene. In high doses these substances can also be toxic for humans.[12]

History[]

A mention by Chinese herbalists suggests that cassia bark was used by humans at least as far back as 2700 B.C. It was a treatment for diarrhea, fevers, and menstrual issues. The Ayurvedic healers of India used it as well to treat similar ailments.

Cassia cinnamon was brought to Egypt around 500 B.C. where it became a valued additive to their embalming mixtures. The Greeks, Romans and ancient Hebrews were the first to use cassia bark as a cooking spice. They also made perfumes with it, and used it for medicinal purposes. The Judeo-Christian bible suggests that it was part of the anointing oil used by Moses. Cinnamon migrated with the Romans. It was established for culinary use by the 17th century in Europe.[13]

See also[]

- Chinese herbology

References[]

- ^ "The Plant List".

- ^ Xi-wen Li, Jie Li & Henk van der Werff. "Cinnamomum cassia". Flora of China. Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Cassia: A real spice or a fake cinnamon". China Business Limited as Regency. 2014-02-26. Archived from the original on 2015-04-28. Retrieved 2014-05-26.

- ^ "Cassia". theepicentre.com.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Wu, Jing-Nuan (2005). An illustrated Chinese materia medica. ProQuest Ebook: Oxford University Press, Incorporated. pp. 165–185.

- ^ Singh J, Singh R, Parasuraman S, Kathiresan S (2020). "Antimicrobial Activity of Extracts of Bark of Cinnamomum cassia and Cinnamomum zeylanicum". Int. J. Pharm. Investigation. 10 (2): 141–145. doi:10.5530/ijpi.2020.2.26.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Wu HZ, Fang ZQ, Cheng PJ (2013). World Century Compendium To Tcm - Volume 1: Fundamentals Of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Hackensack, NJ: World Century Publishing Corporation. pp. 55–82. ISBN 978-1-938134-28-9.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Wong, Ming (1976). La Médecine chinoise par les plantes. Le Corps a Vivre series. Éditions Tchou.

- ^ Zhang, Chunling; Fan, Linhong; Fan, Shunming; Wang, Jiaqi; Luo, Ting; Tang, Yu; Chen, Zhimin; Yu, Lingying (October 1, 2019). "Cinnamomum cassia Presl: A Review of Its Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, Pharmacology and Toxicology". Molecules. 24 (19): 3473. doi:10.3390/molecules24193473. OCLC 8261494774. PMC 6804248. PMID 31557828.

- ^ Hajimonfarednejad, M; Ostovar, M; Raee, M. J; Hashempur, M. H; Mayer, J. G; Heydari, M (2018). "Cinnamon: A systematic review of adverse events". Clinical Nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland). 38 (2): 594–602. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2018.03.013. PMID 29661513.

- ^ NPR: German Christmas Cookies Pose Health Danger

- ^ High daily intakes of cinnamon: Health risk cannot be ruled out. BfR Health Assessment No. 044/2006, 18 August 2006 Archived 19 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine 15p

- ^ Etymology and Brief History of Cassia Cinnamon Mdidea.com>

Further reading[]

- Dalby, Andrew (1996). Siren Feasts: A History of Food and Gastronomy in Greece. London: Routledge.

- Faure, Paul (1987). Parfums et aromates de l'antiquité. Paris: Fayard.

- Paszthoty, Emmerich (1992). Salben, Schminken und Parfüme im Altertum. Mainz, Germany: Zabern.

- Paterson, Wilma (1990). A Fountain of Gardens: Plants and Herbs from the Bible. Edinburgh.

- Chang, Chen-Tien; Chang, Wen-Lun; Hsu, Jaw-Cherng (August 2013). "Chemical composition and tyrosinase inhibitory activity of Cinnamomum cassia essential oil". Botanical Studies. 54 (1): 10. doi:10.1186/1999-3110-54-10. PMC 5432840. PMID 28510850.

External links[]

- Cinnamomum

- Spices

- Plants used in traditional Chinese medicine

- Trees of China

- Endemic flora of China