Cirencester

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2021) |

| Cirencester | |

|---|---|

| Market town | |

| |

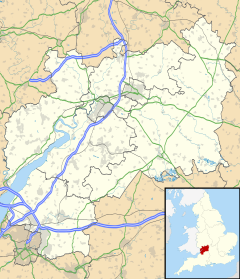

Cirencester Location within Gloucestershire | |

| Population | 19,076 (2011)[1] |

| OS grid reference | SP022021 |

| District |

|

| Shire county |

|

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | CIRENCESTER |

| Postcode district | GL7 |

| Dialling code | 01285 |

| Police | Gloucestershire |

| Fire | Gloucestershire |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| UK Parliament | |

Cirencester (/ˈsaɪrənsɛstər/ (![]() listen), occasionally /ˈsɪstər/ (

listen), occasionally /ˈsɪstər/ (![]() listen); see below for more variations)[3] is a market town in Gloucestershire, England, 80 miles (130 km) west of London. Cirencester lies on the River Churn, a tributary of the River Thames, and is the largest town in the Cotswolds. It is the home of the Royal Agricultural University, the oldest agricultural college in the English-speaking world, founded in 1840.

listen); see below for more variations)[3] is a market town in Gloucestershire, England, 80 miles (130 km) west of London. Cirencester lies on the River Churn, a tributary of the River Thames, and is the largest town in the Cotswolds. It is the home of the Royal Agricultural University, the oldest agricultural college in the English-speaking world, founded in 1840.

The Roman name for the town was Corinium, which is thought to have been associated with the ancient British tribe of the Dobunni, having the same root word as the River Churn.[4] The earliest known reference to the town was by Ptolemy in AD 150. The town's Corinium Museum has an extensive Roman collection.

Cirencester is twinned with the town of Itzehoe, in the Steinburg region of Germany.[5]

Local geography[]

Cirencester lies on the lower dip slopes of the Cotswold Hills, an outcrop of oolitic limestone. Natural drainage is into the River Churn, which flows roughly north to south through the eastern side of the town and joins the Thames near Cricklade a little to the south. The Thames itself rises just a few miles west of Cirencester.

The town is split into five main areas: the town centre, the village of Stratton, the suburb of Chesterton (originally a village outside the town), Watermoor and The Beeches. The village of Siddington to the south of the town is now almost contiguous with Watermoor. Other suburbs include Bowling Green and New Mills. The area and population of these 5 electoral wards are identical to that quoted above. The town serves as a centre for surrounding villages, providing employment, amenities, shops, commerce and education, and as a commuter town for larger centres such as Cheltenham, Gloucester, Swindon and Stroud.

Transport[]

Cirencester is the hub of a road network with routes to Gloucester (A417), Cheltenham (A417/A435), Leamington Spa (A429), Oxford (A40 via the B4425 road), Wantage (A417), Swindon (A419), Chippenham (A429), Bristol, Bath (A433), and Stroud (A419), although only Gloucester, Cheltenham, Stroud and Swindon have bus connections. Cirencester is connected to the M5 motorway at junction 11A, and to the M4 motorway at junctions 15, 17 and 18.

Since the closure of the Kemble to Cirencester branch line to Cirencester Town in 1964, the town has been without its own railway station. Kemble railway station, 3.7 miles (5.9 km) away, is the nearest railhead, served by regular Great Western Railway services between Swindon and Gloucester, with peak-time direct trains to London Paddington station. In November 2020 Kemble to Cirencester was one of 15 grant awards in the second round of the Department for Transport 'Restoring Your Railway Ideas Fund'.

The nearest airports are Bristol, London Heathrow and Birmingham. A general aviation airport, Cotswold Airport, is nearby at Kemble.

History[]

Roman Corinium[]

Cirencester is known to have been an important early Roman area, along with St. Albans and Colchester, and the town includes evidence of significant area roadworks. The Romans built a fort where the Fosse Way crossed the Churn, to hold two quingenary alae tasked with helping to defend the provincial frontier around AD 49, and native Dobunni were drawn from Bagendon, a settlement 3 miles (5 km) to the north, to create a civil settlement near the fort. When the frontier moved to the north after the conquest of Wales, this fort was closed and its fortifications levelled around the year 70, but the town persisted and flourished under the name Corinium.

Even in Roman times, there was a thriving wool trade and industry, which contributed to the growth of Corinium. A large forum and basilica were built over the site of the fort, and archaeological evidence shows signs of further civic growth. There are many Roman remains in the surrounding area, including several Roman villas near the villages of Chedworth and Withington. When a wall was built around the Roman city in the late 2nd century, it enclosed 240 acres (1 km²), making Corinium the second-largest city by area in Britain. The details of the provinces of Britain following the Diocletian Reforms around 296 remain unclear, but Corinium is now generally thought to have been the capital of Britannia Prima. Some historians would date to this period the pillar erected by the governor Lucius Septimus to the god Jupiter, a local sign of the pagan reaction against Christianity during the principate of Julian the Apostate.

Post-Roman and Saxon[]

The Roman amphitheatre still exists in an area known as the Querns to the south-west of the town, but has only been partially excavated. Investigations in the town show that it was fortified in the 5th or 6th centuries. Andrew Breeze argued that Gildas received his later education in Cirencester in the early 6th century, showing that it was still able to provide an education in Latin rhetoric and law at that time.[6] Possibly this was the palace of one of the British kings defeated by Ceawlin in 577. It was later the scene of the Battle of Cirencester, this time between the Mercian king Penda and the West Saxon kings Cynegils and Cwichelm in 628.[7]

The minster church of Cirencester, founded in the 9th or 10th century, was probably a royal foundation. It was made over to Augustinian canons in the 12th century and replaced by the great abbey church.

Norman[]

At the Norman Conquest the royal manor of Cirencester was granted to the Earl of Hereford, William Fitz-Osbern, but by 1075 it had reverted to the Crown. The manor was granted to Cirencester Abbey, founded by Henry I in 1117, and following half a century of building work during which the minster church was demolished, the great abbey church was finally dedicated in 1176. The manor was granted to the Abbey in 1189, although a royal charter dated 1133 speaks of burgesses in the town.

The struggle of the townsmen to gain the rights and privileges of a borough for Cirencester probably began in the same year, when they were amerced for a false presentment, meaning that they had presented false information. Four inquisitions during the 13th century supported the abbot's claims, yet the townspeople remained unwavering in their quest for borough status: in 1342, they lodged a Bill of complaint in Chancery. Twenty townspeople were ordered to Westminster, where they declared under oath that successive abbots had bought up many burgage tenements, and made the borough into an appendage of the manor, depriving it of its separate court. They claimed that the royal charter that conferred on the men of Cirencester the liberties of Winchester had been destroyed 50 years earlier, when the abbot had bribed the burgess who held the charter to give it to him, whereupon the abbot had had it burned. In reply, the abbot refuted these claims, and the case passed on to the King's Bench. When ordered to produce the foundation charter of his abbey the abbot refused, apparently because that document would be fatal to his case, and instead played a winning card. In return for a fine of £300, he obtained a new royal charter confirming his privileges and a writ of supersedeas.

Yet the townspeople continued in their fight: in return for their aid to the Crown against the earls of Kent and Salisbury, Henry IV in 1403 gave the townsmen a Merchant's Guild, although two inquisitions reiterated the abbot's rights. The struggle between the abbot and the townspeople continued, with the abbot's privileges confirmed in 1408‑1409 and 1413, and in 1418 the abbot finally removed this thorn in his side when the guild merchant was annulled, and in 1477 parliament declared that Cirencester was not corporate. After several unsuccessful attempts to re-establish the guild merchant, in 1592 the government of the town was vested in the bailiff of the Lord of the manor.

Tudor[]

As part of the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1539, Henry VIII ordered the total demolition of the Abbey buildings. Today only the Norman Arch and parts of the precinct wall remain above ground, forming the perimeter of a public park in the middle of town. Despite this, the freedom of a borough continued to elude the townspeople, and they only saw the old lord of the manor replaced by a new lord of the manor as the King acquired the abbey's title.

Sheep rearing, wool sales, weaving and woollen broadcloth and cloth-making were the main strengths of England's trade in the Middle Ages, and not only the abbey but many of Cirencester's merchants and clothiers gained wealth and prosperity from the national and international trade. The tombs of these merchants can be seen in the parish church, while their fine houses of Cotswold stone still stand in and around Coxwell Street and Dollar Street. Their wealth funded the rebuilding of the nave of the parish church in 1515–30, to create the large parish church, often referred to as the "Cathedral of the Cotswolds". Other wool churches can be seen in neighbouring Northleach and Chipping Campden.

Civil War[]

The English Civil War came to Cirencester in February 1643 when Royalists and Parliamentarians came to blows in the streets. Over 300 were killed, and 1,200 prisoners were held captive in the church. The townsfolk supported the Parliamentarians but gentry and clergy were for the old order, so that when Charles I of England was executed in 1649 the minister, Alexander Gregory, wrote on behalf of the gentry in the parish register, "O England what did'st thou do, the 30th of this month".

At the end of the English Civil War, King Charles II spent the night of 11 September 1651 in Cirencester, during his escape after the Battle of Worcester on his way to France.

Recent history[]

At the end of the 18th century, Cirencester was a thriving market town, at the centre of a network of turnpike roads with easy access to markets for its produce of grain and wool. A local grammar school provided education for those who could afford it, and businesses thrived in the town, which was the major urban centre for the surrounding area.

In 1789, the opening of the of the Thames and Severn Canal provided access to markets further afield, by way of a link through the River Thames. In 1841, a branch railway line was opened to Kemble to provide a link to the Great Western Railway at Swindon. The Midland and South Western Junction Railway opened a station at Watermoor in 1883. Cirencester thus was served by two railway lines until the 1960s.

The loss of the canal and the direct rail link encouraged dependency on road transport. An inner ring road system was completed in 1975 in an attempt to reduce congestion in the town centre, which has since been augmented by an outer bypass with the expansion of the A417 road. Coaches depart from London Road for Victoria Bus Station in central London and Heathrow Airport, taking advantage of the M4 Motorway. Kemble Station to the west of the town, distinguished by a sheltered garden, is served by fast trains from Paddington station via Swindon.

In 1894, the passing of the Local Government Act brought at last into existence Cirencester's first independent elected body, the Urban District Council. The reorganisation of the local governments in 1974 replaced the Urban District Council with the present two-tier system of Cotswold District Council and Cirencester Town Council. A concerted effort to reduce overhead wiring and roadside clutter has given the town some picturesque street scenes. Many shops cater to tourists and many house family businesses.

Under the patronage of the Bathurst family, the Cirencester area, notably Sapperton, became a major centre for the Arts and Crafts movement in the Cotswolds, when the furniture designer and architect-craftsman Ernest Gimson opened workshops in the early 20th century, and Norman Jewson, his foremost student, practised in the town.

Name[]

The name stem Corin is cognate with Churn (the modern name of the river on which the town is built) and with the stem Cerne in the nearby villages of North Cerney, South Cerney, and Cerney Wick; also on the River Churn. The modern name Cirencester is derived from the cognate root Ciren and the standard -cester ending indicating a Roman fortress or encampment. It seems certain that this name root goes back to pre-Roman times and is similar to the original Brythonic name for the river, and perhaps the settlement. An early Welsh language ecclesiastical list from St David's gives another form of the name Caerceri where Caer is the Welsh for fortress and Ceri is cognate with the other forms of the name.

Pronunciation[]

In ninth-century Old Welsh the city was known as Cair Ceri (literally "Fort Ceri"), translated Cirrenceaster, Cirneceaster, or Cyrneceaster (dative Cirrenceastre, Cirneceastre, Cyrneceastre) in the Old English of the Anglo-Saxons, where ceaster means "fort" or "fortress".[8] The Old English c was pronounced /tʃ/. The Normans mispronounced the /tʃ/ sound as [ts],[9] resulting in the modern name Cirencester (/ˈsaɪrənsɛstər/). The form /ˈsɪsɪtər/, spelled Cirencester or Ciceter, was once used locally. This pronunciation is humorously highlighted in a 1928 limerick from Punch:

There was a young lady of Cirencester

Whose fiancé went down to virencester

By the great Western line,

Which he swore was divine,

And he couldn't have been much explirencester.[10]

This limerick is explained as follows: There was a young lady of /ˈsɪsɪtər/ Whose fiancé went down to /ˈvɪz·ɪtər/ By the Great Western line, Which he swore was divine, And he couldn't have been much /ɪkˈsplɪs.ɪtər/.

There was a young lady of Cirencester Whose fiancé went down to visiter (= visit 'er, visit her) By the Great Western line, Which he swore was divine, And he couldn't have been much expliciter. (= more explicit) "[11]

Sometimes the form Cicester (/ˈsɪsɪstər/) was heard instead. These forms are now very rarely used, while many local people abbreviate the name to Ciren (/ˈsaɪrən/).

Today it is usually /ˈsaɪrənsɛstər/ (as it is spelt) or /ˈsaɪrənstər/, although occasionally it is /ˈsɪsɪstər/, /ˈsɪsɪtər/ or /ˈsɪstər/.

Sites of interest[]

The Church of St. John the Baptist is renowned for its Perpendicular Gothic porch, fan vaults and merchants' tombs.

The town also has a Roman Catholic church dedicated to St Peter; the foundation stone was laid on 20 June 1895. Coxwell Street to the north of Market Square was the original home of the Baptist Church that was founded in 1651, making it one of the oldest Baptist churches in England;[12] the church moved in January 2017 to a new building on Chesterton Lane. The town's Salvation Army hall in Thomas Street occupies the former Temperance Hall built by the Quaker Christopher Bowly in 1846, and is the oldest such hall in the West of England.[13] The Salvation Army first met in Cirencester in 1881.[14]

To the west of the town is Cirencester Park, the seat of Earl Bathurst and the site of one of the finest landscape gardens in England, laid out by Allen Bathurst, 1st Earl Bathurst after 1714. He inherited the estate from his father, Sir Benjamin Bathurst, a Tory Member of Parliament and statesman who made his wealth from his involvement in the slave trade through the Royal Africa Company and the East India Company.

Abbey House was a country house built on the site of the former Cirencester Abbey following its dissolution and demolition at the Reformation in the 1530s. The site was granted in 1564 to Richard Master, physician to Elizabeth I. The house was rebuilt and altered at several dates by the Master family, who still own the agricultural estate. By 1897 the house was let, and it remained in the occupation of tenants until shortly after the Second World War. It was demolished in 1964.

On Cotswold Avenue is the site of a Roman amphitheatre which, while buried, retains its shape in the earthen topography of the small park setting. Cirencester was one of the most substantial cities of Roman-era Britain.

Local politics[]

Before 1974 the town was administered by Cirencester Urban District Council, which was initially based in the upper floors of the south porch of the Church of St. John the Baptist. The council moved to offices in Castle Street in 1897 and to offices in Gosditch Street in 1932.[15][16] In the 1974 reorganisation of local government, the urban district council was replaced by the new Cotswold District Council and Cirencester Town Council was created as the first tier of local government.[17]

The Liberal Democrats are now the dominant political party in Cirencester, winning all eight Cirencester seats available on Cotswold District Council in May 2019; the party has an overall majority there.[18] The Liberal Democrats also took 13 of the 16 seats on the town council at the 2019 local elections; rather than forming a political group, all councillors agreed to work apolitically.[citation needed] The Liberal Democrats have also held the two Gloucestershire County Council seats since the 2013 elections.

Liberal Democrat candidate Joe Harris, aged 18, was elected to the district council for Cirencester Park Ward in May 2011, and became the youngest councillor in the country.[19] Harris was also elected to the county council in the 2013 elections, winning the Cirencester Park Division.[20]

Education[]

The town and the surrounding area have several primary schools and two secondary schools, Cirencester Deer Park School on Stroud Road and Cirencester Kingshill School on Kingshill Lane. It also has an independent school, Rendcomb College, catering for 3 to 18-year-olds. The town used to have a 500-year-old grammar school, which in 1966 joined with the secondary modern to form Cirencester Deer Park School. In 1991, Cirencester College was created, taking over the joint sixth form of Cirencester Deer Park and Cirencester Kingshill schools and the Cirencester site of Stroud College; it is adjacent to Deer Park School on Stroud Road.

Until 1994 the town had a private preparatory school, Oakley Hall. Run in its later years by the Letts family, it closed in 1994 shortly after the retirement of R F B Letts who had led the school since 1962. The grounds of the school are now occupied by housing.

The Royal Agricultural University campus is between the Stroud and Tetbury Roads.

Culture[]

The Sundial Theatre, part of Cirencester College the Bingham Hall[21] and the [22] host drama and musical events by community groups and professional companies.

Cirencester Operatic Society,[23] Cirencester Philharmonia Orchestra,[24] Cirencester Band,[25] Cirencester Male Voice Choir[26] and Cirencester Creative Dance Academy[27] are also based in the town.

Sport[]

Cirencester Town F.C., play in the Southern League Premier Division. The team, known as The Centurions, moved in 2002 from their former ground at Smithsfield on Tetbury Road to the purpose-built Corinium Stadium. The club is designated by The Football Association as a Community Club. As well as the main pitch, there are six additional football pitches, mainly used by the junior football teams. The club has also developed a full-size indoor training area, known as The Arena, which is used for training, for social events, and for 5-a-side leagues throughout the year.[28]

Cirencester has two athletics clubs, Cirencester Athletics and Triathlon Club and Running Somewhere Else.

Cirencester Ladies Netball Club has three squads. The A team play in the 1st division of the Gloucestershire League. The B team in the 3rd Division and the C team in the 5th Division.

The Rugby Club are based at the Whiteway. They have four main teams, a colts, a Youth and Mini sections.

Cirencester Park Polo Club, founded in 1896, is the oldest polo club in the UK.[29] Its main grounds are located in Earl Bathurst's Cirencester Park. It is frequently used by The Prince of Wales and his sons The Duke of Cambridge and Duke of Sussex.[30]

Notable people[]

- Pam Ayres, poet, actor, broadcaster

- Elizabeth Brown, astronomer

- Willie Carson, retired jockey, television commentator

- Rev. Dr. John Clinch, clergyman-physician, the first man to practice vaccination in North America

- Charlie Cooper, actor, writer

- Daisy May Cooper, actor, writer

- Frank Cadogan Cowper, the 'Last PreRaphaelite Artist'

- Jacquie de Creed, stunt woman

- Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, composer, director of music at Cirencester Grammar School from 1959 to 1962[31]

- Dom Joly, comedian, journalist, broadcaster

- William Sinclair Marris, civil servant, colonial administrator, classical scholar

- Mike Patto, musician

- Cozy Powell, drummer

- Lewis Charles Powles, artist

- Theophila Townsend, Quaker writer and activist

- John Woolrich, composer[32]

References[]

- ^ "Parish population 2011". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ^ "The website of Geoffrey Clifton Brown – Current MP for the Cotswold area". Archived from the original on 2 October 2011. Retrieved 19 June 2008.

- ^ Room, Adrian, The Pronunciation of Placenames: A Worldwide Dictionary Archived 17 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine, McFarland, 2007, Pages 6 & 51

- ^ "Cirencester History Summary". Cirencester.co.uk. Archived from the original on 15 July 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ "Town Council – Twinning with Itzehoe". Cirencester.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 30 July 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ Andrew Breeze, 'Gildas and the Schools of Cirencester', The Antiquaries Journal, 90 (2010), p. 135

- ^ Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, sub anno 628.

- ^ Seyer, Samuel (1821). "The Saxon Period". Memoirs Historical and Topographical of Bristol and Its Neighborhood. 1. Bristol. p. 229. Archived from the original on 24 September 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

Asser in his life of Alfred A.D. 879, speaks of 'Cirrenceaster, § which is called in the British language Cair Ceri, which is in the southern part of the Wiccii.'

(In Latin: Cirrenceastre adiit, qui Britannice Cairceri nominatur, quae est in meridiana parte Huicciorum.) - ^ Ekwall, Eilert (1960). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place Names. Oxford University Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-19-869103-7.

- ^ Reed, Langford (1934). "Irreverent Radios". Mr. Punch's Limerick Book. London: R. Cobden–Sanderson Ltd. pp. 65–66.

- ^ "meaning - Humorous limerick on Cirencester / virencester / explirencester. I don't get it". English Language Learners Stack Exchange.

- ^ "Church History". Cirencester Baptist Church. 21 March 2016. Archived from the original on 27 January 2015.

- ^ David Grace. 'Defeating the Demon Drink' in S. Emson and M. Ball(ed.) Cirencester 2002 pp91–98

- ^ Welsford, Jean; Welsford, Alan (August 2010) [1987]. Cirencester: A History and Guide. Amberley Publishing. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-4456-1124-2. Archived from the original on 4 May 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- ^ "No. 42142". The London Gazette (Supplement). 13 September 1960. p. 6249.

- ^ Historic England. "15, Gosditch Street (1187490)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ "19th Century to the present day". Cirencester Town Council. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ Casey, Gemma (11 May 2011). "Reaction to local election results". Wilts and Gloucestershire Standard. Archived from the original on 25 June 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- ^ "Gloucestershire local council election results: Conservatives forge ahead". This is Gloucestershire. 6 May 2011. Archived from the original on 15 January 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ^ Bowen, Anna (3 May 2013). "Conservatives beat UKIP into second place or worse in the Cotswolds". Wilts and Gloucestershire Standard. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ^ "Bingham Hall". binghamhall.co.uk. 24 April 2013. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ "Barn Theatre". barntheatre.org.uk. 30 June 2019. Archived from the original on 29 June 2019. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ "Cirencester Operatic Society". Cirencester Operatic Society. Archived from the original on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ "Cirencester Philharmonia". www.cirencesterphil.co.uk. Archived from the original on 22 February 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ "Cirencester Band". www.cirencesterband.org.uk. Archived from the original on 4 May 2021. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ "Cirencester Male Voice Choir". www.cirencestermvc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ^ "Cirencester Creative Dance Academy". www.ccda.co.uk. Archived from the original on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ "Cirencester Arena". Cirencester Town F.C. Archived from the original on 4 August 2019. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- ^ Social Season – Warwickshire Cup Archived 18 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Debrett's, accessed 31 January 2012

- ^ The young royals: Prince William (21 June 1982). "BBC Prince William Article". Bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ Dunnett, Roderic (August 2009). "Life & Career - Sir Peter Maxwell Davies". maxopus.com. Archived from the original on 17 December 2017.

- ^ "John Woolrich - Biography". Fabermusic.com. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

Bibliography[]

- H. P. R. Finberg. "The Origin of Gloucestershire Towns" in Gloucestershire Studies, edited by H.P.R. Finberg. Leicester: University Press, 1957

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cirencester. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Cirencester. |

- Town Council

- Read a detailed historical record about Cirencester Roman Amphitheatre

- Cirencester at Curlie

- BBC archive film of Cirencester from 1979

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Cirencester". Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 391–392.

- Cirencester

- Towns in Gloucestershire

- Cotswolds

- Cotswold District