Dark triad

In psychology, the dark triad comprises the personality traits of narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy.[1][2][3][4] They are called "dark" because of their malevolent qualities.[5][1][6][7]

Research on the dark triad is used in applied psychology, especially within the fields of law enforcement, clinical psychology, and business management. People scoring high on these traits are more likely to commit crimes, cause social distress and create severe problems for an organization, especially if they are in leadership positions (for more information, see psychopathy, narcissism, and Machiavellianism in the workplace). They also tend to be less compassionate, agreeable, empathetic, satisfied with their lives, and less likely to believe they and others are good.[8]

All three dark triad traits are conceptually distinct although empirical evidence shows them to be overlapping. They are associated with a callous-manipulative interpersonal style.[9]

- Narcissism is characterized by grandiosity, pride, egotism, and a lack of empathy.[10]

- Machiavellianism is characterized by manipulation and exploitation of others, an absence of morality, unemotional callousness, and a higher level of self interest.[11]

- Psychopathy is characterized by continuous antisocial behavior, impulsivity, selfishness, callous and unemotional traits (CU),[12] and remorselessness.[13]

A factor analysis found that among the big five personality traits, low agreeableness is the strongest correlate of the dark triad, while neuroticism and a lack of conscientiousness were associated with some of the dark triad members.[11] Agreeableness and the dark triad show correlated change over development.[14]

History[]

In 1998, McHoskey, Worzel, and Szyarto[15] provoked a controversy by claiming that narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy are more or less interchangeable in normal samples. Delroy L. Paulhus and McHoskey debated these perspectives at a subsequent American Psychological Association (APA) conference, inspiring a body of research that continues to grow in the published literature. Paulhus and Williams found enough behavioral, personality, and cognitive differences between the traits to suggest that they were distinct constructs; however, they concluded that further research was needed to elucidate how and why they overlap.[1]

Components[]

There is a good deal of conceptual and empirical overlap between the dark triad traits. For example, researchers have noted that all three traits share characteristics such as a lack of empathy,[16] interpersonal hostility,[17] and interpersonal offensiveness.[18] Likely due in part to this overlap, a number of measures have recently been developed that attempt to measure all three dark triad traits simultaneously, such as the Dirty Dozen[19] and the short dark triad (SD3).[20]

At their root, however, most of these measures are questionnaire-style and require either self-response or observer-response (e.g., ratings from supervisors or coworkers). Both methods can prove problematic when attempting to measure any socially aversive trait as self-responders may be motivated to deceive.[21] A more specific confound might also exist for dark triad traits and Machiavellianism in particular: individuals who are skilled at deceiving and manipulating others should be perceived as low in deceptiveness and manipulation by others, and are therefore likely to receive inaccurate ratings.[21]

Despite these criticisms and the acknowledged commonalities among the dark triad traits, there is evidence that the constructs are related yet distinct.

Machiavellianism[]

Named after the political philosophy espoused by Niccolò Machiavelli, people who score high on this trait are cynical (in an amoral self-interest sense, not in a doubtful or skeptical sense), unprincipled, and cold, believe in interpersonal manipulation as the key for life success, and behave accordingly.[22] Scores on measures of Machiavellianism correlate negatively with agreeableness (r = −.47) and conscientiousness (r = −.34).[1] Machiavellianism is also significantly correlated with psychopathy.[23]

Narcissism[]

Individuals who score high on narcissism display grandiosity, entitlement, dominance, and superiority.[24] Narcissism has been found to correlate positively with extraversion (r = .42) and openness (r = .38) and negatively with agreeableness (r = −.36).[1] Narcissism has also been found to have a significant correlation with psychopathy.[23]

Psychopathy[]

Considered the most malevolent of the dark triad,[25] individuals who score high on psychopathy show low levels of empathy combined with high levels of impulsivity and thrill-seeking.[26] Psychopathy has been found to correlate with all of the Big Five personality factors: extraversion (r = .34), agreeableness (r = −.25), conscientiousness (r = −.24), neuroticism (r = −.34) and openness (r = .24).[23]

Origins[]

The long-debated "nature versus nurture" issue has been applied to the dark triad. Research has begun to investigate the origins of the dark triad traits. In a similar manner to research on the Big Five personality traits, empirical studies have been conducted in an effort to understand the relative contributions of biology (nature) and environmental factors (nurture) in the development of dark triad traits.

One of the ways in which researchers attempt to dissect the relative influence of genetic and environmental factors on personality (and individual differences more generally) is a broad investigative technique loosely grouped under the heading of "twin studies". For example, in one approach to twin studies,[27][28][23] researchers compare the personality scores of monozygotic (MZ) or identical twins reared together to dizygotic (DZ) or fraternal twins reared together. Because both types of twins in this design are reared together, all twin pairs are regarded as having shared a 100% common environment. In contrast, the monozygotic twins share 100% of their genes whereas the dizygotic twins only share about 50% of their genes. Therefore, for any given personality trait, it is possible to parcel out genetic influences by first obtaining the MZ correlation (reflecting 100% common environment and 100% shared genes) and subtracting the DZ correlation (reflecting 100% common environment and 50% shared genes). This difference represents 50% of the genetic influence; doubled, this number is said to account for 100% of the genetic influence, and is one way to derive an index of heritability (sometimes called the heritability coefficient and represented as h2). Similarly, MZ − h2 may be regarded as an estimate of the influence of the common environment. Finally, because individual differences and the environment are supposed to account for the totality of behavior, it is said that subtracting the sum of h2 and the common environment influence from 1 is equal to the influence of unique or non-shared environments.[citation needed]

Biological[]

All three traits of the dark triad have been found to have substantial genetic components.[27] It has also been found that the observed relationships among the dark triad, and among the dark triad and the Big Five, are strongly driven by individual differences in genes.[22] However, while psychopathy (h2 = 0.64) and narcissism (h2 = 0.59) both have a relatively large heritable component, Machiavellianism (h2 = 0.31) while also moderately influenced by genetics, has been found to be less heritable than the other two traits.[22][23]

Environmental[]

Compared to biological factors, the influence of environmental factors seem to be more subtle and account for less—yet still significant—variation in individual differences as related to the development of dark triad traits.[22] The influence of non-shared or unique environmental factors (definition and mathematical derivation included above at the end of the "Origins" subsection) accounts for a significant amount of the variance in all three dark triad traits (narcissism = 0.41, Machiavellianism = 0.30, psychopathy = 0.32), whereas only Machiavellianism (r = 0.39) has been found to be significantly related to a shared environmental factor.[28] Although it requires substantiation, some researchers have interpreted this latter finding (along with the comparatively lesser heritability noted in the section above) to mean that Machiavellianism is the most likely dark triad trait to be influenced by experience.[16] At the very least, this notion about the modifiability of Machiavellianism does make some sense insofar as that the less variance there is attributable to genetic factors, the more variance there must be attributable to other factors, and "other" factors have traditionally been synopsized as environmental in nature.

Evolutionary[]

Evolutionary theory may also explain the development of dark triad traits.[14] It has been argued that evolutionary behavior predicts not only the development of dark triad personalities, but also the flourishing of such personalities.[29] Indeed, it has been found that individuals demonstrating dark triad personality can be highly successful in society.[22] However, this success is typically short-lived.[22] The main evolutionary argument behind the dark triad traits emphasizes mating strategies.[30][31] This argument focuses on the notion of life history strategy.[32] Life history strategy proposes that individuals differ in reproductive strategies; an emphasis on mating is termed a "fast life" strategy, while an emphasis on parenting is termed a "slow reproductive" strategy.[32] There is some evidence[33][34] that the dark triad traits are related to fast life history strategies; however, there have been some mixed results, and not all three dark triad traits have been related to this strategy. A more detailed approach[35] has attempted to account for some of these mixed results by analyzing the traits at a finer level of detail. These researchers found that while some components of the dark triad are related to a fast life strategy, other components are related to slow reproductive strategies.[35]

Sub-clinical dimensions vs. disorders[]

In general, clinicians treat two of the traits (narcissism and psychopathy) as pathological, something that needs to be treated, and inherently undesirable, e.g. socially condemned or personally counter-productive. However, others argue that adaptive qualities may accompany the maladaptive ones. The evolutionary perspective (above) considers the dark triad to represent different mating strategies. Their frequency in the gene pool requires at least some local adaptation.

The everyday versions of these traits appear in student and community samples, where even high levels can be observed among individuals who manage to get along in daily life. Even in these samples, research indicates correlations with aggression,[36] racism,[37] and bullying[38] among other forms of social aversiveness.

Narcissism was discussed in the writings of Sigmund Freud, and psychopathy as a clinical diagnosis was addressed in the early writings of Hervey Cleckley in 1941 with the publication of The Mask of Sanity.[39] Given the dimensional model of narcissism and psychopathy, complemented by self-report assessments that are appropriate for the general population, these traits can now be studied at the subclinical level.[40] In the general population, the prevalence rates for sub-clinical and clinical psychopathy are estimated at around 1% and 0.2%, respectively.[41][42][43] Unfortunately, there do not seem to be any reliable estimates of either clinical or sub-clinical narcissism in the general population.[44]

With respect to empirical research, psychopathy was not formally studied until the 1970s with the pioneering efforts of Robert Hare, his Psychopathy Checklist (PCL), and its revision (PCL-R).[45] Hare notes in his book, Without Conscience[46] that asking psychopaths to self-report on psychologically important matters does not necessarily provide accurate or unbiased data. However, recent efforts have been made to study psychopathy in the dimensional realm using self-reported instruments, as with the Levenson Primary and Secondary Psychopathy Scales,[47] The Psychopathic Personality Inventory,[48] and the Self-Report Psychopathy Scale.[49]

Similarly, assessment of narcissism required clinical interviews, until the popular "Narcissistic Personality Inventory" was created by Raskin and Hall in 1979.[50] Since the NPI, several other measures have emerged which attempt to provide self-report alternatives for personality disorder assessment.[51] In addition, new instruments have been developed to study "pathological" narcissism[52] as opposed to "grandiose" narcissism, which is what many argue the NPI measures.[53][54]

Machiavellianism has never been referenced in any version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) for psychological disorders. It has been treated as strictly a personality construct. The original published version of the Mach-IV[55] is still the most widely used in empirical research.[56]

Group differences[]

The most pronounced group difference is in gender: numerous studies have shown that men tend to score higher than women on narcissism,[57] Machiavellianism,[58][59][60] and psychopathy,[61][62][63][64] although the magnitude of the difference varies across traits, the measurement instruments, and the age of the participants. One interesting finding related to narcissism—albeit one based on non-representative samples—is that while men continue to score higher than women, it seems that the gender gap has shrunk considerably when comparing cohort data from 1992 and 2006. More specifically, the aforementioned findings indicate that there has been a general increase in levels of narcissism over time among college students of both sexes, but comparatively, the average level of narcissism in women has increased more than the average level of narcissism in men.[57]

There is far less information available on race differences in dark triad traits, and the data that is available is not representative of the population at-large. For instance, a 2008 research study using undergraduate participants found that Caucasians reported higher levels of narcissism relative to Asians.[65][66] Similarly, another 2008 study using undergraduate participants found that Caucasians tended to score slightly higher than non-Caucasians on Machiavellianism.[59] When attempting to discern whether there are ethnic differences in psychopathy, researchers have addressed the issue using different measurement instruments (e.g., the Self-Report Psychopathy Scale and The Psychopathic Personality Inventory), but no race differences have been found regardless of the measure used.[67][68] Additionally, when comparing Caucasians and African Americans from correctional, substance abuse, and psychiatric samples—groups with typically high prevalence rates of psychopathy—researchers again failed to find any meaningful group differences in psychopathy.[69] However, in controversial research conducted by Richard Lynn, a substantial racial difference in psychopathy was found. Lynn proposes "that there are racial and ethnic differences in psychopathic personality conceptualised as a continuously distributed trait, such that high values of the trait are present in blacks and Native Americans, intermediate values in Hispanics, lower values in whites and the lowest values in East Asians."[70] However this research has been heavily criticized for not distinguishing between psychopathy and other anti-social behaviors, confusing between personality and behavioral concepts of psychopathy and presuming rather than demonstrating genetic & or evolutionary causes for supposed disparities.[71]

The focal variable when analyzing generational or cohort differences in dark triad traits has tended to be narcissism, arising from the hypothesis that so-called "Generation Me" or "Generation Entitlement" would exhibit higher levels of narcissism than previous generations. Indeed, based on analyses of responses to the Narcissistic Personality Inventory collected from over 16,000 U.S. undergraduate students between 1979 and 2006, it was concluded that average levels of narcissism had increased over time.[57] Similar results were obtained in a follow-up study that analyzed the changes within each college campus.[72][73] present conflicting evidence and argue that there have not been large changes in disposition or behavioral strategies across generations, although they do note that the current generation is less trusting and more cynical, which are both changes that might be indicative of an increase in Machiavellianism. An alternative perspective explored group differences in the dark triad and how they relate to positive emotion.[74] Applying Structural equation modeling and Latent Profile Analysis a type of Mixture model to establish patterns in UK, US, and Canadian students, four groups were found: “unhappy but not narcissistic”, “vulnerable narcissism”, “happy non-narcissism” and “grandiose narcissism”. Some extrapolations on how a person might deal with these groups of individuals in practice have been suggested.[75]

Perspectives[]

In the workplace[]

Oliver James identifies each of the three dark triadic personality traits as typically being prevalent in the workplace (see also Machiavellianism in the workplace, narcissism in the workplace and psychopathy in the workplace).[76] Furnham (2010)[22] has identified that the dark triad is related to the acquisition of leadership positions and interpersonal influence. In a meta-analysis of dark triad and workplace outcomes, Jonason and colleagues (2012) found that each of the dark triad traits were related to manipulation in the workplace, but each via unique mechanisms. Specifically, Machiavellianism was related with the use of excessive charm in manipulation, narcissism was related with the use of physical appearance, and psychopathy was related with physical threats.[77] Jonason and colleagues also found that the dark triad traits fully mediated the relationship between gender and workplace manipulation. The dark triad traits have also been found to be fairly well-represented in upper-level management and CEOs.[78]

Internet trolls[]

Recent studies have found that people who are identified as trolls tend to have dark personality traits and show signs of sadism, antisocial behavior, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism.[79][80][81] The 2013 case study suggested that there are a number of similarities between anti-social and flame trolling activities and the 2014 survey indicated that trolling is an Internet manifestation of everyday sadism. Both studies suggest that this trolling may be linked to bullying in both adolescents and adults.

As a mating strategy[]

Studies have suggested that on average, those who exhibit the dark triad of personality traits have an accelerated mating strategy, reporting more sex partners, more favorable attitudes towards casual sex,[82] lowered standards in their short-term mates,[83] a tendency to steal or poach mates from others,[84] more risk-taking in the form of substance abuse,[34] a tendency to prefer immediate but smaller amounts of money over delayed but larger amounts of money,[85] limited self-control and greater incidence of ADHD symptoms[33] and a pragmatic and game-playing romance style.[86] These traits have been identified as part of a fast life strategy that appears to be enacted by an exploitative, opportunistic, and protean approach to life in general[87] and at work.[77]

The evidence is mixed regarding the exact link between the dark triad and reproductive success. For example, there is a lack of empirical evidence for reproductive success in the case of psychopathy.[13] Additionally, these traits are not universally short-term-oriented[33] nor are they all impulsive.[16] Furthermore, much of the research reported pertaining to the dark triad cited in the above paragraph is based on statistical procedures that assume the dark triad are a single construct, in spite of genetic[23] and meta-analytic evidence to the contrary.[21]

Appearance[]

Several academic studies have found evidence that people with dark triad personalities are judged as slightly better-looking than average on first sight.[88] Two studies have determined that this is because people with dark triad traits put more effort into their appearance, and the difference in attractiveness disappears when "dressed down" with bland clothing and without make up.[89][90] Two more studies found that only narcissistic subjects were judged to be better-looking, but the other dark triad traits of Machiavellianism and psychopathy had no correlation with looks.[91][92] Facial features associated with dark triad traits tend to be rated as less attractive.[93]

Related concepts[]

Big Five[]

The five factor model of personality has significant relationships with the dark triad combined and with each of the dark triad's traits. The dark triad overall is negatively related to both agreeableness and conscientiousness.[22] More specifically, Machiavellianism captures a suspicious versus trusting view of human nature which is also captured by the Trust sub-scale on the agreeableness trait.[94] Extraversion captures similar aspects of assertiveness, dominance, and self-importance as narcissism.[94] Narcissism also is positively related to the achievement striving and competence aspects of Conscientiousness. Psychopathy has the strongest correlations with low dutifulness and deliberation aspects of Conscientiousness.[22]

Honesty-humility[]

The honesty-humility factor from the HEXACO model of personality is used to measure sincerity, fairness, greed avoidance, and modesty. Honesty-Humility has been found to be strongly, negatively correlated to the dark triad traits.[95] Likewise, all three dark triad traits are strongly negatively correlated with Honesty-Humility.[22] The conceptual overlap of the three traits which represents a tendency to manipulate and exploit others for personal gain defines the negative pole of the honesty-humility factor.[96] Typically, any positive effects from the DT and low H-H occur at the individual level, that is, any benefits are conferred onto the beholder of the traits (e.g., successful mating, obtainment of leadership positions) and not onto others or society at large. A study found that individuals who score low in Honesty-Humility have higher levels of self-reported creativity.[97]

Dark tetrad[]

Several researchers have suggested expanding the dark triad to contain a fourth dark trait - everyday sadism. It is defined as the enjoyment of cruelty, is the most common addition.[98] While sadism is highly correlated with the dark triad, researchers have shown that sadism predicts anti-social behavior beyond the dark triad.[38][99] Sadism shares common characteristics with psychopathy and antisocial behavior (lack of empathy, readiness for emotional involvement, inflicting suffering), although Reidy et al. (2011)[100] showed that sadism distinctively predicted unprovoked aggression separate from psychopathy.[101]

Furthermore, sadism predicted delinquent behavior separately from the other dark triad traits when evaluating high school students.[101]

Harmful behavior against living creatures, brutal and destructive amoral dispositions, and criminal recidivism were additionally more prominently predicted by sadism than psychopathic traits.[101]

Studies on how sadists gain pleasure from cruelty to subjects were applied towards testing people who possessed dark triad traits. Results showed that only people exhibiting traits of sadism derived a sense of pleasure from acts of cruelty, concluding that sadism encompasses distinctly cruel traits not covered by the rest of the dark triad, therefore deserving of its position within the dark tetrad.[102]

Vulnerable dark triad[]

The vulnerable dark triad (VDT) comprises three related and similar constructs: vulnerable narcissism, sociopathy, and borderline personality disorder. A study found that these three constructs are significantly related to one another and manifest similar nomological networks. Although the VDT members are related to negative emotionality and antagonistic interpersonal styles, they are also related to introversion and disinhibition. The study does note however that its findings are based largely on the self-reports of parents of white undergrad students rather than information gleaned from clinical evaluation.[103]

Malignant narcissism[]

Within the clinical/pathological realm, narcissism can manifest itself in a particularly severe form known as malignant narcissism. Malignant narcissism presents not only with signs and symptoms of grandiose narcissism, but also includes features of paranoia, sadism, aggression, and psychopathy (particularly antisocial behaviors).[104]

Light triad[]

Influenced by the dark triad, Scott Barry Kaufman proposed a "light triad" of personality virtues: humanism, Kantianism, and faith in humanity.[105][106][107] High scorers on humanism are more likely to value others' dignity and self worth. High scorers on Kantianism are more likely to see others as people, not as a means to an end. High scorers for faith in humanity are more likely to believe others are fundamentally good.[108][109][110] When comparing individuals who take both dark triad and light triad tests, the average person skewed substantially towards light triad traits.[110] This test was not an inversion of the dark triad test. In fact, Kaufman intended to avoid reversing the coding of the dark triad and instead focused on characteristics that were conceptually opposite from the dark triad test. Kaufman (2019)[8] showed that the light triad could be measured with a reliable scale and is distinct from the inverse of the dark triad's Big Five and HEXACO model traits. The light triad predicts positive and negative outcomes regarding Agreeableness and Honesty-Humility and expands on understanding the dark triad as a useful contrasting analog.[8]

Individuals who score high on light triad traits also report higher levels of: religiosity, spirituality, life satisfaction, acceptance of others, belief that they and others are good, compassion, empathy, higher self-esteem, authenticity, stronger sense of self, positive enthusiasm, having a quiet ego, openness to experience and conscientiousness.[8] Additionally, those who score higher on the light triad scale are overall intellectually curious, secure in their attachments to others, and are more tolerant to other perspectives.[108] Negative correlations include less motives for achievement and self-enhancement (even though the light triad was positively related to productivity and competence). In contrast to the character strengths of the dark triad, the light triad was uncorrelated with bravery or assertiveness. Lack of such characteristics may turn problematic for individuals attempting to reach one's more challenging goals and fully self-actualizing.[111]

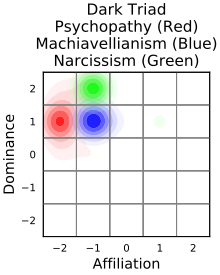

Atlas of Personality, Emotion and Behaviour[]

The Atlas of Personality, Emotion and Behaviour[112] is a catalogue of 20,500 words descriptive of personality, emotion and behaviour. The words in the catalogue were scored according to a two dimensional matrix taxonomy with orthogonal dimensions of affiliation and dominance. Adjectives representing the behavioural patterns described by the Dark Triad were scored according to the atlas and visualised using kernel density plots in two dimensions. The atlas clearly delineates the three components of the Dark Triad, narcissism (green), Machiavellianism (blue), and psychopathy (red).

See also[]

- Antisocial Personality Disorder

- Evil

- Evolutionary psychology

- Macdonald triad

- Life history theory

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Paulhus, Delroy L; Williams, Kevin M (December 2002). "The Dark Triad of personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and Psychopathy". Journal of Research in Personality. 36 (6): 556–563. doi:10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00505-6.

- ^ Robert M. Regoli; John D. Hewitt; Matt DeLisi (20 April 2011). Delinquency in Society: The Essentials. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-7637-7790-6.

- ^ W. Keith Campbell; Joshua D. Miller (7 July 2011). The Handbook of Narcissism and Narcissistic Personality Disorder: Theoretical Approaches, Empirical Findings, and Treatments. John Wiley & Sons. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-118-02924-4.

- ^ Mark R. Leary; Rick H. Hoyle (5 June 2009). Handbook of individual differences in social behavior. Guilford Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-59385-647-2.

- ^ Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic; Sophie von Stumm; Adrian Furnham (23 February 2011). The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Individual Differences. John Wiley & Sons. p. 527. ISBN 978-1-4443-4310-6.

- ^ Leonard M. Horowitz; Stephen Strack, Ph.D. (14 October 2010). Handbook of Interpersonal Psychology: Theory, Research, Assessment and Therapeutic Interventions. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 252–55. ISBN 978-0-470-88103-3. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ^ David Lacey (17 March 2009). Managing the Human Factor in Information Security: How to Win Over Staff and Influence Business Managers. John Wiley & Sons. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-470-72199-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Kaufman, Scott Barry; Yaden, David Bryce; Hyde, Elizabeth; Tsukayama, Eli (12 March 2019). "The Light vs. Dark Triad of Personality: Contrasting Two Very Different Profiles of Human Nature". Frontiers in Psychology. 10: 467. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00467. PMC 6423069. PMID 30914993.

- ^ Jones, D. N.; Paulhus, D. L. (2010). "Differentiating the dark triad within the interpersonal circumplex". In Horowitz, L. M.; Strack, S. N. (eds.). Handbook of interpersonal theory and research. New York: Guilford. pp. 249–67.

- ^ Kohut, H. (1977). The Restoration of the Self. New York: International Universities Press. ISBN 9780823658107.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jakobwitz, Sharon; Egan, Vincent (January 2006). "The dark triad and normal personality traits". Personality and Individual Differences. 40 (2): 331–339. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.07.006.

- ^ Frick, Paul J.; White, Stuart F. (April 2008). "Research Review: The importance of callous-unemotional traits for developmental models of aggressive and antisocial behavior". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 49 (4): 359–375. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01862.x. PMID 18221345.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Skeem, Jennifer L.; Polaschek, Devon L. L.; Patrick, Christopher J.; Lilienfeld, Scott O. (15 December 2011). "Psychopathic Personality". Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 12 (3): 95–162. doi:10.1177/1529100611426706. PMID 26167886. S2CID 8521465.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Klimstra, Theo A.; Jeronimus, Bertus F.; Sijtsema, Jelle J.; Denissen, Jaap J.A. (April 2020). "The unfolding dark side: Age trends in dark personality features". Journal of Research in Personality. 85: 103915. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2020.103915.

- ^ McHoskey, John W.; Worzel, William; Szyarto, Christopher (1998). "Machiavellianism and psychopathy". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 74 (1): 192–210. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.1.192. PMID 9457782.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Jones, Daniel N.; Paulhus, Delroy L. (October 2011). "The role of impulsivity in the Dark Triad of personality". Personality and Individual Differences. 51 (5): 679–682. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.04.011.

- ^ Lynam, Donald R.; Gaughan, Eric T.; Miller, Joshua D.; Miller, Drew J.; Mullins-Sweatt, Stephanie; Widiger, Thomas A. (2011). "Assessing the basic traits associated with psychopathy: Development and validation of the Elemental Psychopathy Assessment". Psychological Assessment. 23 (1): 108–124. doi:10.1037/a0021146. PMID 21171784.

- ^ Egan, Vincent; McCorkindale, Cara (December 2007). "Narcissism, vanity, personality and mating effort". Personality and Individual Differences. 43 (8): 2105–2115. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2007.06.034.

- ^ Jonason, Peter K.; Webster, Gregory D. (June 2010). "The dirty dozen: A concise measure of the dark triad". Psychological Assessment. 22 (2): 420–432. doi:10.1037/a0019265. PMID 20528068.

- ^ Jones, Daniel N.; Paulhus, Delroy L. (February 2014). "Introducing the Short Dark Triad (SD3): A Brief Measure of Dark Personality Traits". Assessment. 21 (1): 28–41. doi:10.1177/1073191113514105. PMID 24322012. S2CID 17524487.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Furnham, Adrian; Richards, Steven C.; Paulhus, Delroy L. (March 2013). "The Dark Triad of Personality: A 10 Year Review: Dark Triad of Personality". Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 7 (3): 199–216. doi:10.1111/spc3.12018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Vernon, Philip A.; Villani, Vanessa C.; Vickers, Leanne C.; Harris, Julie Aitken (January 2008). "A behavioral genetic investigation of the Dark Triad and the Big 5". Personality and Individual Differences. 44 (2): 445–452. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2007.09.007.

- ^ Corry, N.; Merritt, R.D.; Mrug, S.; Pamp, B. (2008). "The factor structure of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory". Journal of Personality Assessment. 90 (6): 593–600. doi:10.1080/00223890802388590. PMID 18925501. S2CID 29486199.

- ^ Rauthmann, J.F. (2012). "The Dark Triad and interpersonal perception: Similarities and differences in the social consequences of narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy". Social Psychological and Personality Science. 3 (4): 487–496. doi:10.1177/1948550611427608. S2CID 690757.

- ^ Hare, R.D. (1985). "Comparison of procedures for the assessment of psychopathy". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 53 (1): 7–16. doi:10.1037/0022-006x.53.1.7. PMID 3980831.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Petrides, K. V.; Vernon, Philip A.; Schermer, Julie Aitken; Veselka, Livia (February 2011). "Trait Emotional Intelligence and the Dark Triad Traits of Personality". Twin Research and Human Genetics. 14 (1): 35–41. doi:10.1375/twin.14.1.35. PMID 21314254. S2CID 4202896.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Vernon, Philip A.; Martin, Rod A.; Schermer, Julie Aitken; Mackie, Ashley (April 2008). "A behavioral genetic investigation of humor styles and their correlations with the Big-5 personality dimensions". Personality and Individual Differences. 44 (5): 1116–1125. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2007.11.003.

- ^ Mealey, Linda (4 February 2010). "The sociobiology of sociopathy: An integrated evolutionary model". Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 18 (3): 523–41. doi:10.1017/s0140525x00039595. S2CID 53956461.

- ^ Jonason, Peter K.; Li, Norman P.; Webster, Gregory D.; Schmitt, David P. (February 2009). "The dark triad: Facilitating a short-term mating strategy in men". European Journal of Personality. 23 (1): 5–18. doi:10.1002/per.698. S2CID 12854051.

- ^ Brumbach, Barbara Hagenah; Figueredo, Aurelio José; Ellis, Bruce J. (6 February 2009). "Effects of Harsh and Unpredictable Environments in Adolescence on Development of Life History Strategies". Human Nature. 20 (1): 25–51. doi:10.1007/s12110-009-9059-3. PMC 2903759. PMID 20634914.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rushton, J.Philippe (January 1985). "Differential K theory: The sociobiology of individual and group differences". Personality and Individual Differences. 6 (4): 441–452. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(85)90137-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Jonason, Peter K.; Tost, Jeremy (October 2010). "I just cannot control myself: The Dark Triad and self-control". Personality and Individual Differences. 49 (6): 611–615. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.05.031.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jonason, Peter K.; Koenig, Bryan L.; Tost, Jeremy (19 November 2010). "Living a fast life: The Dark Triad and Life History Theory". Human Nature. 21 (4): 428–442. doi:10.1007/s12110-010-9102-4. S2CID 142541037.

- ^ Jones D.N.; Paulhus D. L. (2010). "Different provocations trigger aggression in narcissists and psychopaths". Social Psychological and Personality Science. 1: 12–18. doi:10.1177/1948550609347591. S2CID 144224401.

- ^ Hodson, G. M.; Hogg, S. M.; MacInnis, C. C. (2009). "The role of "dark personalities" (narcissism, Machiavellianism, psychopathy), Big Five personality factors, and ideology in explaining prejudice". Journal of Research in Personality. 43 (4): 686–690. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2009.02.005.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Chabrol H.; Van Leeuwen N.; Rodgers R.; Séjourné S. (2009). "Contributions of psychopathic, narcissistic, Machiavellian, and sadistic personality traits to juvenile delinquency". Personality and Individual Differences. 47 (7): 734–39. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2009.06.020.

- ^ Cleckley, Hervey (1941). The mask of sanity: an attempt to clarify some issues about the so called psychopathic personality. Henry Kimpton. OCLC 222417020.[page needed]

- ^ LeBreton, J. M.; Binning, J. F.; Adorno, A. J. (2005). "Sub-clinical psychopaths". In Thomas, Jay C.; Segal, Daniel L. (eds.). Comprehensive Handbook of Personality and Psychopathology , Personality and Everyday Functioning. Wiley. pp. 388–411. ISBN 978-0-471-48837-8.

- ^ Babiak, P.; Neumann, C. S.; Hare, R. D. (2010). "Corporate psychopathy: Talking the walk". Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 28 (2): 174–193. doi:10.1002/bsl.925. PMID 20422644. S2CID 15946623.

- ^ Coid, Jeremy; Yang, Min; Ullrich, Simone; Roberts, Amanda; Hare, Robert D. (March 2009). "Prevalence and correlates of psychopathic traits in the household population of Great Britain" (PDF). International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 32 (2): 65–73. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2009.01.002. PMID 19243821.

- ^ Neumann, C. S.; Hare, R. D. (2008). "Psychopathic traits in a large community sample: Links to violence, alcohol use, and intelligence". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 76 (5): 893–899. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.76.5.893. PMID 18837606. S2CID 1789397.

- ^ Foster, J. D.; Campbell, W. K. (2007). "Are there such things as "narcissists" in social psychology? A taxometric analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory". Personality and Individual Differences. 43 (6): 1321–1332. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2007.04.003.

- ^ Hare, R.D., (1991). The Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems.[page needed]

- ^ Hare, R. D. (1999). Without conscience: The disturbing world of the psychopaths among us. New York: Guilford Press.

- ^ Levenson M. R.; Kiehl K. A.; Fitzpatrick C. M. (1995). "Assessing psychopathic attributes in a noninstitutionalized population". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 68 (1): 151–58. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.68.1.151. PMID 7861311.

- ^ Lilienfeld S. O.; Andrews B. P. (1996). "Development and preliminary validation of a self-report measure of psychopathic personality traits in noncrimnal population". Journal of Personality Assessment. 66 (3): 488–524. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa6603_3. PMID 8667144.

- ^ Paulhus, D. L., Neumann, C. S., & Hare, R. D. (2015). Manual for the Self-Report Psychopathy scales (4th ed.). Toronto, Canada: Multi-Health Systems.[page needed]

- ^ Raskin, Robert N.; Hall, Calvin S. (October 1979). "A Narcissistic Personality Inventory". Psychological Reports. 45 (2): 590. doi:10.2466/pr0.1979.45.2.590. PMID 538183. S2CID 5395685.

- ^ Hyler, S.E. (1994). Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire-4 (Unpublished test). New York: NYSPI.

- ^ Pincus A. L.; Ansell E. B.; Pimentel C. A.; Cain N. M.; Wright A. G. C.; Levy K. N. (2009). "Initial construction and validation of the Pathological Narcissism Inventory". Psychological Assessment. 21 (3): 365–79. doi:10.1037/a0016530. PMID 19719348. S2CID 18001836.

- ^ Miller, J. D.; Campbell, W. K. (2008). "Comparing clinical and Social-Personality Conceptutalizations of narcissism". Journal of Personality. 76 (3): 449–476. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00492.x. PMID 18399956. S2CID 6794645.

- ^ Wink P (1991). "Two faces of narcissism". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 61 (4): 590–97. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.61.4.590. PMID 1960651. S2CID 12617826.

- ^ Christie, R., & Geis, F. L. (1970). Studies in Machiavellianism. New York: Academic Press.[page needed]

- ^ Jones, D. N., & Paulhus, D. L. (2009). Machiavellianism. In M. R. Leary & R. H. Hoyle (Eds.), Handbook of Individual Differences in Social Behavior (pp. 93–108). New York: Guilford.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Twenge, Jean M.; Konrath, Sara; Foster, Joshua D.; Keith Campbell, W.; Bushman, Brad J. (August 2008). "Egos Inflating Over Time: A Cross-Temporal Meta-Analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory". Journal of Personality. 76 (4): 875–902. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.586.7541. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00507.x. PMID 18507710.

- ^ Chonko, Lawrence B. (31 August 2016). "Machiavellianism: Sex Differences in the Profession of Purchasing Management". Psychological Reports. 51 (2): 645–646. doi:10.2466/pr0.1982.51.2.645. S2CID 145577786.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dahling, Jason J.; Whitaker, Brian G.; Levy, Paul E. (5 February 2008). "The Development and Validation of a New Machiavellianism Scale". Journal of Management. 35 (2): 219–257. doi:10.1177/0149206308318618. S2CID 54937924.

- ^ Wertheim, Edward G.; Widom, Cathy S.; Wortzel, Lawrence H. (1978). "Multivariate analysis of male and female professional career choice correlates". Journal of Applied Psychology. 63 (2): 234–242. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.63.2.234.

- ^ Levenson, M. R.; Kiehl, K. A.; Fitzpatrick, C. M. (1995). "Assessing psychopathic attributes in a noninstitutionalized population". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 68 (1): 151–158. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.68.1.151. PMID 7861311.

- ^ Lilienfeld, S. O.; Andrews, B. P. (1996). "Development and preliminary validation of a self-report measure of psychopathic personality traits in noncriminal population". Journal of Personality Assessment. 66 (3): 488–524. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa6603_3. PMID 8667144.

- ^ Cale, Ellison M.; Lilienfeld, Scott O. (November 2002). "Sex differences in psychopathy and antisocial personality disorder". Clinical Psychology Review. 22 (8): 1179–1207. doi:10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00125-8. PMID 12436810.

- ^ Zágon, Ilona K.; Jackson, Henry J. (July 1994). "Construct validity of a psychopathy measure". Personality and Individual Differences. 17 (1): 125–135. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(94)90269-0.

- ^ Trzesniewski, Kali H.; Donnellan, M. Brent; Robins, Richard W. (February 2008). "Do Today's Young People Really Think They Are So Extraordinary?". Psychological Science. 19 (2): 181–188. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02065.x. PMID 18271867. S2CID 205573466.

- ^ Twenge, Jean M.; Foster, Joshua D. (December 2008). "Mapping the scale of the narcissism epidemic: Increases in narcissism 2002–2007 within ethnic groups". Journal of Research in Personality. 42 (6): 1619–1622. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2008.06.014.

- ^ Epstein, Monica K.; Poythress, Norman G.; Brandon, Karen O. (26 July 2016). "The Self-Report Psychopathy Scale and Passive Avoidance Learning". Assessment. 13 (2): 197–207. doi:10.1177/1073191105284992. PMID 16672734. S2CID 22930917.

- ^ Lander, Gwendoline C.; Lutz-Zois, Catherine J.; Rye, Mark S.; Goodnight, Jackson A. (January 2012). "The differential association between alexithymia and primary versus secondary psychopathy". Personality and Individual Differences. 52 (1): 45–50. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.08.027.

- ^ Skeem, Jennifer L.; Edens, John F.; Camp, Jacqueline; Colwell, Lori H. (2004). "Are there ethnic differences in levels of psychopathy? A meta-analysis". Law and Human Behavior. 28 (5): 505–527. doi:10.1023/b:lahu.0000046431.93095.d8. PMID 15638207. S2CID 17224850.

- ^ Lynn, Richard (January 2002). "Racial and ethnic differences in psychopathic personality". Personality and Individual Differences. 32 (2): 273–316. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00029-0.

- ^ Skeem, Jennifer L; Edens, John F; Sanford, Glenn M; Colwell, Lori H (October 2003). "Psychopathic personality and racial/ethnic differences reconsidered: a reply to Lynn (2002)". Personality and Individual Differences. 35 (6): 1439–1462. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00361-6.

- ^ Twenge, Jean M.; Campbell, W. Keith (5 May 2017). "Birth Cohort Differences in the Monitoring the Future Dataset and Elsewhere: Further Evidence for Generation Me—Commentary on Trzesniewski & Donnellan (2010)". Perspectives on Psychological Science. 5 (1): 81–88. doi:10.1177/1745691609357015. PMID 26162065. S2CID 17239061.

- ^ Trzesniewski, Kali H.; Donnellan, M. Brent (5 May 2017). "Rethinking 'Generation Me': A Study of Cohort Effects from 1976-2006". Perspectives on Psychological Science. 5 (1): 58–75. doi:10.1177/1745691609356789. PMID 26162063. S2CID 12426094.

- ^ Egan, Vincent; Chan, Stephanie; Shorter, Gillian W. (2014). "The Dark Triad, happiness and subjective well-being" (PDF). Personality and Individual Differences. 67 (1): 17–22. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.004.

- ^ Whitbourne, Susan Krauss (30 August 2014). "8 Ways to Handle a Narcissist". Psychology Today.

- ^ James, Oliver (2013). Office Politics: How to Thrive in a World of Lying, Backstabbing and Dirty Tricks. ISBN 978-1-4090-0557-5.[page needed]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jonason, Peter K.; Slomski, Sarah; Partyka, Jamie (February 2012). "The Dark Triad at work: How toxic employees get their way". Personality and Individual Differences. 52 (3): 449–453. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.11.008.

- ^ Amernic, Joel H.; Craig, Russell J. (23 February 2010). "Accounting as a Facilitator of Extreme Narcissism". Journal of Business Ethics. 96 (1): 79–93. doi:10.1007/s10551-010-0450-0. JSTOR 40836190. S2CID 145545000.

- ^ Buckels, Erin E.; Trapnell, Paul D.; Paulhus, Delroy L. (September 2014). "Trolls just want to have fun". Personality and Individual Differences. 67: 97–102. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.016.

- ^ "Internet Trolls Are Narcissists, Psychopaths, and Sadists".

- ^ Anderson, Nate (20 February 2014). "Science confirms: Online trolls are horrible people (also, sadists!)". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ^ Jonason, Peter K.; Li, Norman P.; Webster, Gregory D.; Schmitt, David P. (February 2009). "The dark triad: Facilitating a short-term mating strategy in men". European Journal of Personality. 23 (1): 5–18. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.650.5749. doi:10.1002/per.698. S2CID 12854051.

- ^ Jonason, Peter K.; Valentine, Katherine A.; Li, Norman P.; Harbeson, Carmelita L. (October 2011). "Mate-selection and the Dark Triad: Facilitating a short-term mating strategy and creating a volatile environment". Personality and Individual Differences. 51 (6): 759–763. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.648.3614. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.06.025.

- ^ Jonason, Peter K.; Li, Norman P.; Buss, David M. (March 2010). "The costs and benefits of the Dark Triad: Implications for mate poaching and mate retention tactics". Personality and Individual Differences. 48 (4): 373–378. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2009.11.003.

- ^ Jonason, P. K.; Li, N. P.; Teicher, E. A. (2010). "Who is James Bond?:The Dark Triad as an agentic social style". Individual Differences Research. 8: 111–120.

- ^ Jonason, Peter K.; Kavanagh, Phillip (October 2010). "The dark side of love: Love styles and the Dark Triad". Personality and Individual Differences. 49 (6): 606–610. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.05.030. hdl:10983/15422.

- ^ Jonason, Peter K.; Webster, Gregory D. (March 2012). "A protean approach to social influence: Dark Triad personalities and social influence tactics". Personality and Individual Differences. 52 (4): 521–526. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.11.023.

- ^ Carter, Gregory Louis; Campbell, Anne C.; Muncer, Steven (January 2014). "The Dark Triad personality: Attractiveness to women". Personality and Individual Differences. 56: 57–61. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2013.08.021.

- ^ Grewal, Daisy (27 November 2012). "Psychology Uncovers Sex Appeal of Dark Personalities". Scientific American.

- ^ Holtzman, Nicholas S.; Strube, Michael J (4 October 2012). "People With Dark Personalities Tend to Create a Physically Attractive Veneer". Social Psychological and Personality Science. 4 (4): 461–467. doi:10.1177/1948550612461284. S2CID 16213035.

- ^ Dufner, Michael; Rauthmann, John F.; Czarna, Anna Z.; Denissen, Jaap J. A. (2 April 2013). "Are Narcissists Sexy? Zeroing in on the Effect of Narcissism on Short-Term Mate Appeal". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 39 (7): 870–882. doi:10.1177/0146167213483580. PMID 23554177. S2CID 7712753.

- ^ Back, Mitja D.; Schmukle, Stefan C.; Egloff, Boris (2010). "Why are narcissists so charming at first sight? Decoding the narcissism–popularity link at zero acquaintance". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 98 (1): 132–145. doi:10.1037/a0016338. PMID 20053038.

- ^ Brewer, Gayle; Christiansen, Paul; Dorozkinaite, Diana; Ingleby, Beth; O'Hagan, Lauren; Williams, Charlotte; Lyons, Minna (April 2019). "A drunk heart speaks a sober mind: Alcohol does not influence the selection of short-term partners with dark triad traits". Personality and Individual Differences. 140: 61–64. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2017.11.028. Lay summary.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hunter, J. E.; Gerbing, D. W.; Boster, F. J. (1982). "Machiavellian beliefs and personality: Construct invalidity of the Machiavellianism dimension". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 43 (6): 1293–1305. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.43.6.1293.

- ^ Aghababaei, N.; Mohammadtabar, S.; Saffarinia, M. (2014). "Dirty Dozen vs. the H factor: Comparison of the Dark Triad and Honesty–Humility in prosociality, religiosity, and happiness". Personality and Individual Differences. 67: 6–10. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2014.03.026.

- ^ Lee, K.; Ashton, M. C.; Wiltshire, J.; Bourdage, J. S.; Visser, B. A.; Gallucci, A. (2013). "Sex, power, and money: Prediction from the Dark Triad and Honesty–Humility". European Journal of Personality. 27 (2): 169–184. doi:10.1002/per.1860. S2CID 146205562.

- ^ Silvia, Paul J.; Kaufman, James C.; Reiter-Palmon, Roni; Wigert, Benjamin (October 2011). "Cantankerous creativity: Honesty–Humility, Agreeableness, and the HEXACO structure of creative achievement". Personality and Individual Differences. 51 (5): 687–689. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.06.011.

- ^ "Everyday Sadists Take Pleasure In Others' Pain". Association for Psychological Science. Archived from the original on 2018-05-27. Retrieved 2018-05-26.

- ^ Buckels, Erin E.; Jones, Daniel N.; Paulhus, Delroy L. (November 2013). "Behavioral Confirmation of Everyday Sadism". Psychological Science. 24 (11): 2201–2209. doi:10.1177/0956797613490749. PMID 24022650. S2CID 30675346.

- ^ Reidy, Dennis E.; Zeichner, Amos; Seibert, L. Alana (February 2011). "Unprovoked Aggression: Effects of Psychopathic Traits and Sadism: Psychopathy, Sadism, and Unprovoked Aggression". Journal of Personality. 79 (1): 75–100. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00691.x. PMID 21223265.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Međedović, Janko; Petrović, Boban (November 2015). "The Dark Tetrad: Structural Properties and Location in the Personality Space". Journal of Individual Differences. 36 (4): 228–236. doi:10.1027/1614-0001/a000179.

- ^ "Everyday Sadism: Throwing Light on the Dark Triad". Association for Psychological Science – APS. Retrieved 2020-04-09.

- ^ Miller, Joshua D.; Dir, Ally; Gentile, Brittany; Wilson, Lauren; Pryor, Lauren R.; Campbell, W. Keith (October 2010). "Searching for a Vulnerable Dark Triad: Comparing Factor 2 Psychopathy, Vulnerable Narcissism, and Borderline Personality Disorder". Journal of Personality. 78 (5): 1529–1564. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00660.x. PMID 20663024. S2CID 7923414.

- ^ Lenzenweger, Mark F.; Clarkin, John F.; Caligor, Eve; Cain, Nicole M.; Kernberg, Otto F. (2018). "Malignant Narcissism in Relation to Clinical Change in Borderline Personality Disorder: An Exploratory Study". Psychopathology. 51 (5): 318–325. doi:10.1159/000492228. PMID 30184541. S2CID 52160230.

- ^ Oakes, Kelly. "The 'light triad' that can make you a good person". BBC. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ "Light Triad Scale". Scott Barry Kaufman. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ Kaufman, Scott Barry; Yaden, David Bryce; Hyde, Elizabeth; Tsukayama, Eli (2019-03-12). "The Light vs. Dark Triad of Personality: Contrasting Two Very Different Profiles of Human Nature". Frontiers in Psychology. 10: 467. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00467. PMC 6423069. PMID 30914993.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Light Triad of Personality". Psychology Today. Retrieved 2020-05-11.

- ^ "The Light Triad: Psychologists Outline the Personality Traits of Everyday Saints". Discover Magazine. Retrieved 2020-05-11.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Oakes, Kelly. "The 'light triad' that can make you a good person". www.bbc.com. Retrieved 2020-05-11.

- ^ "The Light Triad vs. Dark Triad of Personality".

- ^ Mobbs, Anthony E. D. (21 January 2020). "An atlas of personality, emotion and behaviour". PLOS ONE. 15 (1): e0227877. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1527877M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0227877. PMC 6974095. PMID 31961895.

External links[]

- Jonason, Peter K.; Webster, Gregory D. (June 2010). "The dirty dozen: A concise measure of the dark triad". Psychological Assessment. 22 (2): 420–432. doi:10.1037/a0019265. PMID 20528068.

- Jones, Daniel N.; Paulhus, Delroy L. (9 December 2013). "Introducing the Short Dark Triad (SD3)". Assessment. 21 (1): 28–41. doi:10.1177/1073191113514105. PMID 24322012. S2CID 17524487.

- Mooney, Chris (February 14, 2014). "Internet Trolls Really Are Horrible People: Narcissistic, Machiavellian, psychopathic, and sadistic". Slate.

- Hartley, Dale (8 September 2015). "Meet the Machiavellians". Psychology Today.

- Machiavellianism, Cognition, and Emotion Psych Central

- Dark triad

- Applied psychology

- Machiavellianism

- Narcissism

- Personality disorders

- Personality traits

- Psychological concepts

- Psychopathy