Day of Infamy speech

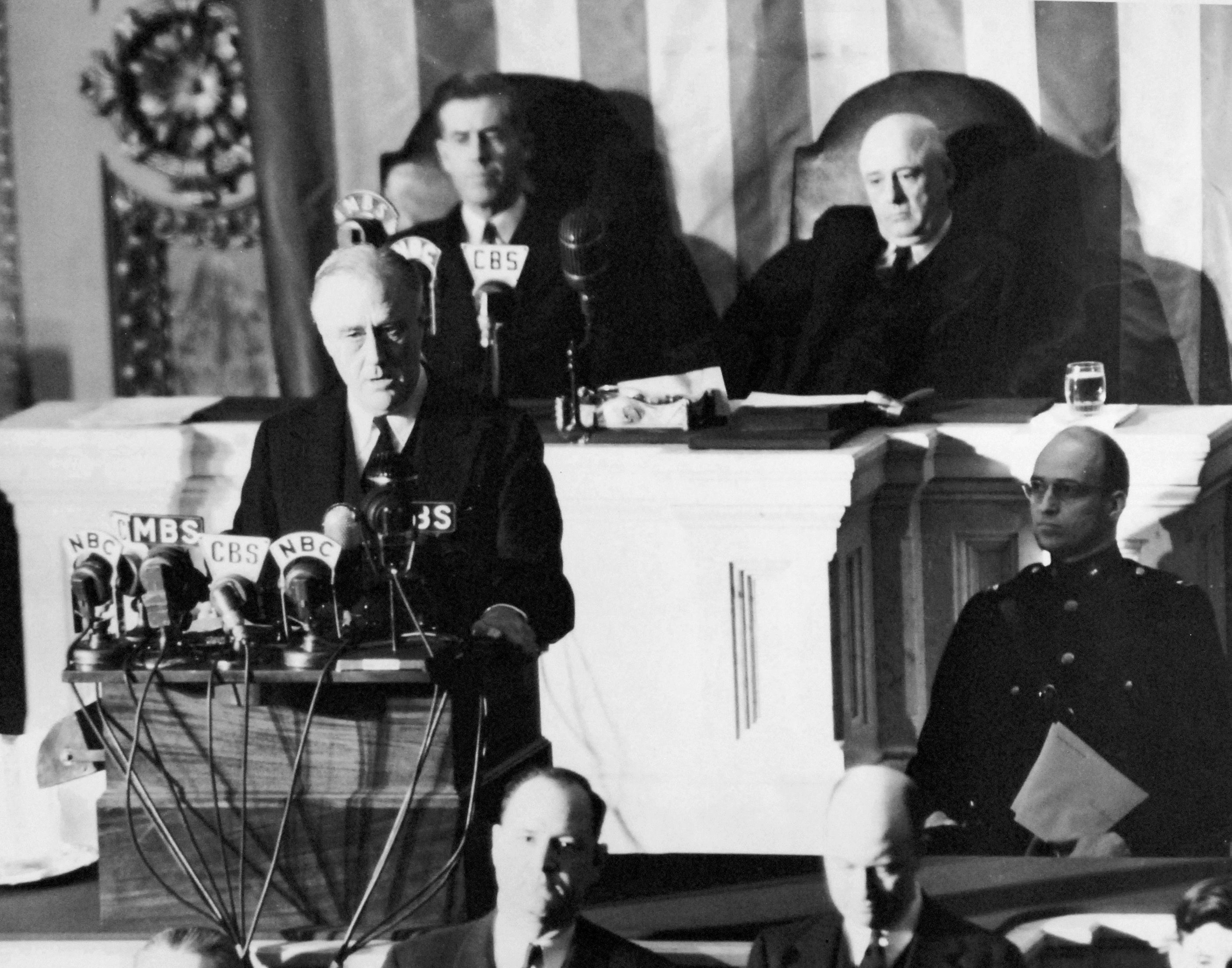

The "Day of Infamy" speech was delivered by United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt to a Joint Session of the U.S. Congress on December 8, 1941, one day after the Empire of Japan's attack on the U.S. military bases at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii and the Philippines along with the Japanese declaration of war on the United States and the British Empire.[1][2][3][4][5] The name derives from the first line of the speech: Roosevelt describing the previous day as "a date which will live in infamy".[6]

Within an hour of the speech, Congress passed a formal declaration of war against Japan and officially brought the U.S. into World War II. The address is one of the most famous American political speeches.[7]

Analysis[]

The Infamy Speech was brief, running to just a little over seven minutes. Secretary of State Cordell Hull had recommended that the President devote more time to a fuller exposition of Japanese-American relations and the lengthy, but unsuccessful, effort to find a peaceful solution. However, Roosevelt kept the speech short in the belief that it would have a more dramatic effect.[8]

His revised statement was all the stronger for its emphatic insistence that posterity would forever endorse the American view of the attack. It was intended not merely as a personal response by the President, but as a statement on behalf of the entire American people in the face of a great collective trauma. In proclaiming the indelibility of the attack, and expressing outrage at its "dastardly" nature, the speech worked to crystallize and channel the response of the nation into a collective response and resolve.[9]

The first paragraph of FDR's speech was carefully worded to reinforce Roosevelt's portrayal of the United States as the innocent victim of unprovoked Japanese aggression. The wording was deliberately passive. Rather than taking the active voice—i. e., "Japan attacked the United States"—Roosevelt chose to put in the foreground the object being acted upon, namely the United States, to emphasize America's status as a victim.[10] The theme of "innocence violated" was further reinforced by Roosevelt's recounting of the ongoing diplomatic negotiations with Japan, which the president characterized as having been pursued cynically and dishonestly by the Japanese government while it was secretly preparing for war against the United States.[11]

Roosevelt consciously sought to avoid making the sort of more abstract appeal that had been issued by President Woodrow Wilson in his own speech to Congress in April 1917, when the United States entered World War I.[12] Wilson laid out the strategic threat posed by Germany and stressed the idealistic goals behind America's participation in the war. During the 1930s, however, American public opinion turned strongly against such themes, and was wary of, if not actively hostile to, idealistic visions of remaking the world through a "just war". Roosevelt, therefore, chose to make an appeal aimed more at the gut level—in effect, an appeal to patriotism, rather than to idealism. Nonetheless, he took pains to draw a symbolic link with the April 1917 declaration of war: when he went to Congress on December 8, 1941, he was accompanied by Edith Bolling Wilson, President Wilson's widow.[13]

The "infamy framework" adopted by Roosevelt was given additional resonance by the fact that it followed the pattern of earlier narratives of great American defeats. The Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876 and the sinking of the USS Maine in 1898 had both been the source of intense national outrage, and a determination to take the fight to the enemy. Defeats and setbacks were on each occasion portrayed as being merely a springboard towards an eventual and inevitable victory. According to Sandra Silberstein, Roosevelt's speech followed a well-established tradition of how "through rhetorical conventions, presidents assume extraordinary powers as the commander in chief, dissent is minimized, enemies are vilified, and lives are lost in the defense of a nation once again united under God".[14]

Roosevelt expertly employed the idea of kairos, which relates to speaking in a timely manner;[15] this made the Infamy Speech powerful and rhetorically important. Delivering his speech on the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt presented himself as immediately ready to face this issue, indicating its importance to both him and the nation. The timing of the speech, in coordination with Roosevelt's powerful war rhetoric, allowed the immediate and almost unanimous approval of Congress to go to war. Essentially, Roosevelt's speech and timing extended his executive powers to not only declaring war but also making war, a power that constitutionally belongs to Congress.[citation needed]

The overall tone of the speech was one of determined realism. Roosevelt made no attempt to paper over the great damage that had been caused to the American armed forces, noting (without giving figures, as casualty reports were still being compiled) that "very many American lives have been lost" in the attack. However, he emphasized his confidence in the strength of the American people to face up to the challenge posed by Japan, citing the "unbounded determination of our people". He sought to re-assure the public that steps were being taken to ensure their safety, noting his own role as "Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy" (the United States Air Force was part of the United States Army at this time) and declaring that he had already "directed that all measures be taken for our defense".

Roosevelt also made a point of emphasizing that "our people, our territory and our interests are in grave danger" and highlighted reports of Japanese attacks in the Pacific between Hawaii and San Francisco. In so doing, he sought to silence the isolationist movement which had campaigned so strongly against American involvement in the war in Europe. If the territory and waters of the continental United States—not just outlying possessions such as the Philippines—was seen as being under direct threat, isolationism would become an unsustainable course of action. Roosevelt's speech had the desired effect, with only one representative, Jeannette Rankin, voting against the declaration of war he sought; the wider isolationist movement collapsed almost immediately.

The speech's "infamy" line is often misquoted as "a day that will live in infamy". However, Roosevelt quite deliberately chose to emphasize the date—December 7, 1941—rather than the day of the attack, a Sunday, which he mentioned only in the last line when he said, "... Sunday, December 7th, 1941, ...". He sought to emphasize the historic nature of the events at Pearl Harbor, implicitly urging the American people never to forget the attack and memorialize its date. Notwithstanding, the term "day of infamy" has become widely used by the media to refer to any moment of supreme disgrace or evil.[16]

Impact and legacy[]

Roosevelt's speech had an immediate and long-lasting impact on American politics. Thirty-three minutes after he finished speaking, Congress declared war on Japan, with only one Representative, Jeannette Rankin, voting against the declaration. The speech was broadcast live by radio and attracted the largest audience in US radio history, with over 81% of American homes tuning in to hear the President.[8] The response was overwhelmingly positive, both within and outside of Congress. Judge Samuel Irving Rosenman, who served as an adviser to Roosevelt, described the scene:

It was a most dramatic spectacle there in the chamber of the House of Representatives. On most of the President's personal appearances before Congress, we found applause coming largely from one side—the Democratic side. But this day was different. The applause, the spirit of cooperation, came equally from both sides. ... The new feeling of unity which suddenly welled up in the chamber on December 8, the common purpose behind the leadership of the President, the joint determination to see things through, were typical of what was taking place throughout the country.[17]

The White House was inundated with telegrams praising the president's stance ("On that Sunday, we were dismayed and frightened, but your unbounded courage pulled us together."[18]). Recruiting stations were jammed with a surge of volunteers, and had to go on 24-hour duty to deal with the crowds seeking to sign up, in numbers reported to be twice as high as after Woodrow Wilson's declaration of war in 1917. The anti-war and isolationist movement collapsed in the wake of the speech, with even the president's fiercest critics falling into line. Charles Lindbergh, who had been a leading isolationist, declared:

Now [war] has come and we must meet it as united Americans regardless of our attitude in the past toward the policy our Government has followed. ... Our country has been attacked by force of arms, and by force of arms we must retaliate. We must now turn every effort to building the greatest and most efficient Army, Navy and Air Force in the world.[19]

Roosevelt's framing of the Pearl Harbor attack became, in effect, the standard American narrative of the events of December 7, 1941. Hollywood enthusiastically adopted the narrative in a number of war films, such as Wake Island, the Academy Award-winning Air Force and the films Man from Frisco (1944), and Betrayal from the East (1945); all included actual radio reports of the pre-December 7 negotiations with the Japanese, reinforcing the message of enemy duplicity. Across the Pacific (1942), Salute to the Marines (1943), and Spy Ship (1942), used a similar device, relating the progress of United States–Japanese relations through newspaper headlines. The theme of American innocence betrayed was also frequently depicted on screen, the melodramatic aspects of the narrative lending themselves naturally to the movies.[20]

The President's description of December 7, 1941 as "a date which will live in infamy" was borne out; the date very quickly became shorthand for the Pearl Harbor attack in much the same way that November 22, 1963 and September 11, 2001 became inextricably associated with the assassination of John F. Kennedy and the September 11 attacks, respectively.[21][22][23][24] The slogans "Remember December 7th" and "Avenge December 7" were adopted as a rallying cry and were widely displayed on posters and lapel pins.[25] Prelude to War (1942), the first of Frank Capra's Why We Fight film series (1942–45), urged Americans to remember the date of the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, September 18, 1931, "as well as we remember December 7th, 1941, for on that date in 1931, the war we are now fighting began".[26] The symbolism of the date was highlighted in a scene in the 1943 film Bombardier, in which the leader of a group of airmen walks up to a calendar on the wall, points to the date ("December 7, 1941") and tells his men: "Gentlemen, there's a date we will always remember—and they'll never forget!"[27]

Twenty-two years later, the continuing resonance of the Infamy Speech was demonstrated following the assassination of John F. Kennedy, which many commentators also compared with Pearl Harbor in terms of its lasting impression on many worldwide.[28][29][30]

Sixty years later, the continuing resonance of the Infamy Speech was demonstrated following the September 11 attacks, which many commentators also compared with Pearl Harbor in terms of its lasting impression on many worldwide.[31] In the days following the attacks, Richard Jackson noted in his book Writing the War on Terrorism: Language, Politics and Counter-terrorism that "there [was] a deliberate and sustained effort" on the part of the George W. Bush administration to "discursively link September 11, 2001 to the attack on Pearl Harbor itself",[32] both by directly invoking Roosevelt's Infamy Speech[33] and by re-using the themes employed by Roosevelt in his speech. In Bush's speech to the nation on September 11, 2001, he contrasted the "evil, despicable acts of terror" with the "brightest beacon for freedom and opportunity" that America represented in his view.[34] Sandra Silberstein drew direct parallels between the language used by Roosevelt and Bush, highlighting a number of similarities between the Infamy Speech and Bush's presidential address of September 11.[14] Similarly, Emily S. Rosenberg noted rhetorical efforts to link the conflicts of 1941 and 2001 by re-utilizing World War II terminology of the sort used by Roosevelt, such as using the term "axis" to refer to America's enemies (as in the "Axis of Evil").[13]

Spanish Prime Minister José Maria Aznar referenced the speech hours after the 2004 Madrid train bombings, saying, "On March 11, 2004, it already occupies its place in the history of infamy."[35]

Daniel Immerwahr wrote that, in the speech's editing, Roosevelt elevated Hawaii as part of America, and downgraded the Philippines as foreign.[36]

On January 6, 2021, following the storming of the Capitol, incoming Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer added that date to the "very short list of dates in American history that will live forever in infamy."[37]

Media[]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

An annotated version of the speech, showing the original wording "a date which will live in world history"

Anti-war protest sign prior to U.S. entry into World War II.

Franklin D. Roosevelt signing the declaration of war against Japan.

"Avenge December 7!" US Government propaganda poster of 1942

See also[]

- Events leading to the attack on Pearl Harbor

- Japanese declaration of war on the United States and the British Empire

- SS Cynthia Olson, a US ship sunk in the Pacific on December 7, referred to in the speech

Notes[]

- ^ Presidential Materials, September 11: Bearing Witness to History, Smithsonian Institution (2002) ("Printed copy of the Presidential address to Congress Reminiscent of Franklin D. Roosevelt's address to Congress after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor")

- ^ Address by the President of the United States, December 8, 1941, in Declarations of a State of War with Japan and Germany, Senate Document No. 148 (77th Congress, 1st Session), at p. 7, reprinted at the University of Virginia School of Law project page, Peter DeHaven Sharp, ed.

- ^ See Senate Document No. 148 (77th Congress, 1st Session), in Congressional Serial Set (1942)

- ^ William S. Dietrich, In the shadow of the rising sun: the political roots of American economic decline (1991), p. xii.

- ^ Franklin Odo, ed., The Columbia documentary history of the Asian American experience, p. 77.

- ^ Joseph McAuley (7 December 2015). "FDR's 'Pearl Harbor Speech,' then and now". America Magazine. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- ^ "FDR's "Day of Infamy" Speech: Crafting a Call to Arms", Prologue magazine, US National Archives, Winter 2001, Vol. 33, No. 4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brown 1998, pp. 117–120

- ^ Neil J. Smelser, in Cultural Trauma and Collective Identity, p. 69. University of California Press, 2004. ISBN 0-520-23595-9.

- ^ James Jasinski, Sourcebook on Rhetoric: key concepts in contemporary rhetorical studies. Sage Publications Inc, 2001. ISBN 0-7619-0504-9.

- ^ Hermann G. Steltner, "War Message: December 8, 1941 — An Approach to Language", in Landmark Essays on Rhetorical Criticism ed. Thomas W. Benson. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1993. ISBN 1-880393-08-5.

- ^ Onion, Rebecca (2014-12-08). "FDR's First Draft of His "Day of Infamy" Speech, With His Notes". Slate. Retrieved 2015-11-16.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Emily S Rosenberg, A Date Which Will Live: Pearl Harbor in American Memory. Duke University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8223-3206-X.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sandra Silberstein, War of Words: Language, Politics, and 9/11, p. 15. Routledge, 2002. ISBN 0-415-29047-3.

- ^ Poulakos, John (1983). "Toward a Sophistic Definition of Rhetoric". Philosophy & Rhetoric. 16 (1): 35–48. JSTOR 40237348.

- ^ "Day of infamy", Merriam-Webster's Dictionary of Allusions, ed. Elizabeth Webber, Mike Feinsilber. Merriam-Webster, 1999. ISBN 0-87779-628-9.

- ^ Samuel Irving Rosenman, quoted in Brown 1998, p. 119

- ^ Quoted in Brown 1998, p. 119

- ^ Quoted in Brown 1998, p. 120

- ^ Barta 1998, pp. 85–87

- ^ Brinkley, David (2003). Brinkley's Beat: People, Places, and Events That Shaped My Time. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0-375-40644-7.

- ^ White, Theodore H. (1965). The Making of the President, 1964. New York: Atheneum Publishers. p. 6. LCCN 65018328.

- ^ Dinneen, Joseph F. (November 24, 1963). "A Shock Like Pearl Harbor". The Boston Globe. p. 10. – via Boston Globe Archive (subscription required)

- ^ "United in Remembrance, Divided over Policies". September 1, 2011.

- ^ Robert J. Sickels, The 1940s, p. 6. Greenwood Press, 2004. ISBN 0-313-31299-0.

- ^ Quoted by Benjamin L. Alpers, "This Is The Army", in The World War II Reader, ed. Gordon Martel, p. 167. Routledge, 2004. ISBN 0-415-22402-0.

- ^ Quoted in Barta, 1998, p. 87.

- ^ White, Theodore H. (1965). The Making of the President, 1964. New York: Atheneum Publishers. p. 6. LCCN 65018328.

- ^ Dinneen, Joseph F. (November 24, 1963). "A Shock Like Pearl Harbor". The Boston Globe. p. 10. – via Boston Globe Archive (subscription required)

- ^ "United in Remembrance, Divided over Policies". September 1, 2011.

- ^ See for instance CNN, "Day of Terror — a 21st century 'day of infamy'", September 2001.

- ^ Richard Jackson, Writing the War on Terrorism: language, politics and counter-terrorism, p. 33. Manchester University Press, 2005.

- ^ See e. g., Paul Wolfowitz, "Standup of US Northern Command", speech of October 1, 2002: "Although September 11th has taken its place alongside December 7th as a date that will live in infamy ..."

- ^ George W. Bush, Address to the Nation of September 11, 2001.

- ^ Sciolino, Elaine (11 March 2004). "Spain Struggles to Absorb Worst Terrorist Attack in Its History". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- ^ Immerwahr, Daniel (15 February 2019). "How the US has hidden its empire". The Guardian. United Kingdom. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

Immerwahr, Daniel (28 February 2019). How to Hide an Empire : A Short History of the Greater United States. Vintage Publishing. pp. 14–16. ISBN 978-1-84792-399-8. - ^ "The Latest: Trump promises 'orderly transition' on Jan. 20". AP News. Associated Press. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

References[]

- Barta, Tony, ed. (1998). Screening the past: film and the representation of history. Westport, CT [u.a.]: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-95402-1.

- Brown, Robert J. (1998). Manipulating the ether : the power of broadcast radio in thirties America. Jefferson, NC [u.a.]: McFarland. ISBN 9780786403974.

- Freidel, Frank (1990). Franklin D. Roosevelt: A Rendezvous with Destiny. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0-316-29260-5.

External links[]

- Video of the speech in congress on YouTube

- Transcript

- Recording of the speech

- "FDR's "Day of Infamy" Speech: Crafting a Call to Arms" – article from the National Archives and Records Administration on the speech with images of Roosevelt's original draft of the text

- "The Pearl Harbour Speech" on Dailymotion, the speech animated with kinetic typography

- Attack on Pearl Harbor

- World War II speeches

- Speeches by Franklin D. Roosevelt

- 1941 in American politics

- 1941 speeches

- American political neologisms

- American political catchphrases

- 1941 in international relations

- Joint sessions of the United States Congress

- 77th United States Congress

- December 1941 events

- United States National Recording Registry recordings