Dekulakization

| Dekulakization | |

|---|---|

| Part of Collectivization in the Soviet Union | |

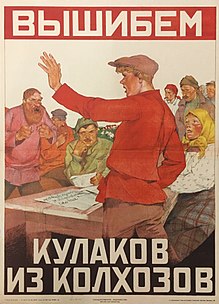

A parade under the banners "We will liquidate the kulaks as a class" and "All to the struggle against the wreckers of agriculture" | |

| Location | Soviet Union |

| Date | 1917–1933 |

Attack type | Mass murder, deportation, starvation |

| Deaths | 390,000 or 530,000–600,000[1] |

| Perpetrators | Secret police of the Soviet Union |

Dekulakization (Russian: раскулачивание, raskulachivanie; Ukrainian: розкуркулення, rozkurkulennia) was the Soviet campaign of political repressions, including arrests, deportations, or executions of millions of kulaks (prosperous peasants) and their families in the 1929–1932 period of the first five-year plan. To facilitate the expropriations of farmland, the Soviet government portrayed kulaks as class enemies of the Soviet Union.

More than 1.8 million peasants were deported in 1930–1931.[2][3][4] The campaign had the stated purpose of fighting counter-revolution and of building socialism in the countryside. This policy, carried out simultaneously with collectivization in the Soviet Union, effectively brought all agriculture and all the labourers in Soviet Russia under state control.

Hunger, disease, and mass executions during dekulakization led to approximately 390,000 or 530,000–600,000 deaths from 1929 to 1933.[5][6] The results soon became known outside the Soviet Union.

Under Vladimir Lenin[]

In November 1917, at a meeting of delegates of the committees of poor peasants, Vladimir Lenin announced a new policy to eliminate what were believed to be wealthy Soviet peasants, known as kulaks: "If the kulaks remain untouched, if we don't defeat the freeloaders, the czar and the capitalist will inevitably return."[7] In July 1918, Committees of the Poor were created to represent poor peasants, which played an important role in the actions against the kulaks, and led the process of redistribution of confiscated lands and inventory, food surpluses from the kulaks. This launched the beginning of a great crusade against grain speculators and kulaks.[8] Before being dismissed in December 1918, the Committees of the Poor had confiscated 50 million hectares of kulak land.[9]

Under Joseph Stalin[]

| Mass repression in the Soviet Union |

|---|

| Economic repression |

| Political repression |

|

| Ideological repression |

| Ethnic repression |

|

Joseph Stalin announced the "liquidation of the kulaks as a class" on 27 December 1929.[2] Stalin had said: "Now we have the opportunity to carry out a resolute offensive against the kulaks, break their resistance, eliminate them as a class and replace their production with the production of kolkhozes and sovkhozes."[10] The Politburo of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) formalized the decision in a resolution titled "On measures for the elimination of kulak households in districts of comprehensive collectivization" on 30 January 1930. All kulaks were assigned to one of three categories:[2]

- Those to be shot or imprisoned as decided by the local secret political police.

- Those to be sent to Siberia, the North, the Urals, or Kazakhstan, after confiscation of their property.

- Those to be evicted from their houses and used in labour colonies within their own districts.

Those kulaks that were sent to Siberia and other unpopulated areas performed hard labor working in camps that would produce lumber, gold, coal and many other resources that the Soviet Union needed for its rapid industrialization plans.[11] In fact, a high ranking member of the OGPU (the secret police) shared his vision for a new penal system that would establish villages in northern Soviet Union that could specialize in extracting natural resources and help Stalin's industrialization.[12]

An OGPU secret-police functionary, Yefim Yevdokimov (1891–1939), played a major role in organizing and supervising the round-up of peasants and the mass executions.[citation needed]

Classicide[]

In February 1928, the Pravda newspaper published for the first time materials that claimed to expose the kulaks; they described widespread domination by the rich peasantry in the countryside and invasion by kulaks of Communist party cells.[13] Expropriation of grain stocks from kulaks and middle-class peasants was called a "temporary emergency measure"; temporary emergency measures turned into a policy of "eliminating the kulaks as a class" by the 1930s.[13] Sociologist Michael Mann described the Soviet attempt to collectivize and liquidate perceived class enemies as fitting his proposed category of classicide.[14]

The party's appeal to the policy of eliminating the kulaks as a class had been formulated by Stalin, who stated: "In order to oust the kulaks as a class, the resistance of this class must be smashed in open battle and it must be deprived of the productive sources of its existence and development (free use of land, instruments of production, land-renting, right to hire labour, etc.). That is a turn towards the policy of eliminating the kulaks as a class. Without it, talk about ousting the kulaks as a class is empty prattle, acceptable and profitable only to the Right deviators."[15]

In 1928, the Right Opposition of the All-Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) was still trying to support the prosperous peasantry and soften the struggle against the kulaks. In particular, Alexei Rykov, criticizing the policy of dekulakization and "methods of war communism", declared that an attack on the kulaks should be carried out but not by methods of so-called dekulakization. He argued against taking action against individual farming in the village, the productivity of which was two times lower than in European countries. He believed that the most important task of the party was the development of the individual farming of peasants with the help of the government.[16]

The government increasingly noticed an open and resolute protest among the poor against the well-to-do middle peasants.[17] The growing discontent of the poor peasants was reinforced by the famine in the countryside. The Bolsheviks preferred to blame the "rural counterrevolution" of the kulaks, intending to aggravate the attitude of the people towards the party: "We must repulse the kulak ideology coming in the letters from the village. The main advantage of the kulak is bread embarrassments." Red Army peasants sent letters supporting anti-kulak ideology: "The kulaks are the furious enemies of socialism. We must destroy them, don't take them to the kolkhoz, you must take away their property, their inventory." The letter of the Red Army soldier of the 28th Artillery Regiment became widely known: "The last bread is taken away, the Red Army family is not considered. Although you are my dad, I do not believe you. I'm glad that you had a good lesson. Sell bread, carry surplus – this is my last word."[18][19]

Liquidation[]

The "liquidation of kulaks as a class"[20] was the name of a Soviet policy enforced in 1930–1931 for forced uncompensated alienation of property (expropriation) from portion of peasantry and isolation of victims from such actions by way of their forceful deportation from their place of residence.[21] The official goal of kulak liquidation came without precise instructions, and encouraged local leaders to take radical action, which resulted in physical elimination. The campaign to liquidate the kulaks as a class constituted the main part of Stalin's social engineering policies in the early 1930s.[22]

See also[]

- Cambodian genocide

- Collectivization in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic

- Committees of Poor Peasants

- Decossackization

- Population transfer in the Soviet Union

- Holodomor

- Involuntary settlements in the Soviet Union

- Land reform in North Vietnam

- Mass killings of landlords under Mao Zedong

- Mass killings under communist regimes

- Red Terror

References[]

- ^ Hildermeier, Die Sowjetunion, p. 38 f.

- ^ a b c Robert Conquest (1986) The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505180-7.

- ^ Nicolas Werth, Karel Bartošek, Jean-Louis Panné, Jean-Louis Margolin, Andrzej Paczkowski, Stéphane Courtois, The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression, Harvard University Press, 1999, hardcover, 858 pages, ISBN 0-674-07608-7

- ^ Lynne Viola The Unknown Gulag. The Lost World of Stalin's Special Settlements Oxford University Press 2007, hardback, 320 pages ISBN 978-0-19-518769-4

- ^ Pohl, J. Otto (1997). The Stalinist penal system : a statistical history of Soviet repression and terror, 1930–1953. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. p. 58. ISBN 0-7864-0336-5. OCLC 37187550.

- ^ Hildermeier, Die Sowjetunion, p. 38 f.

- ^ А.Арутюнов «Досье Ленина без ретуши. Документы. Факты. Свидетельства.», Москва: Вече, 1999

- ^ Ленин В. И. Полн. собр. сочинений. Т. 36. С. 361—363; Т. 37. С. 144.

- ^ Краткий курс истории ВКП(б) (1938 год) // Репринтное воспроизведение стабильного издания 30-40-х годов. Москва, изд. «Писатель», 1997 г.

- ^ Robert Service: Stalin, a biography, page 266.

- ^ Applebaum, Anne (2004). Gulag : a history (First Anchor books ed.). New York. pp. 97–127. ISBN 1-4000-3409-4. OCLC 55203139.

- ^ Viola, Lynne (2007). The unknown gulag : the lost world of Stalin's special settlements. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 2–5. ISBN 978-0-19-518769-4. OCLC 71266656.

- ^ a b Л. Д. Троцкий «Материалы о революции. Преданная революция. Что такое СССР и куда он идет»

- ^ Alvarez, Alex (2009). Genocidal Crimes. Routledge. p. 25. ISBN 9781134035816.

- ^ И. В. Сталин «К вопросу о ликвидации кулачества как класса»

- ^ Н. В. Валентинов, Ю. Г. Фельштинский «Наследники Ленина»

- ^ РГВА, ф. 4, оп. 1, д. 107, л. 215. Цит. по: Чуркин В. Ф. Самоидентификация крестьянства на переломном этапе своей истории. // История государства и права, 2006, N 7

- ^ В. Ф. Чуркин, кандидат исторических наук. «Самоидентификация крестьянства на переломном этапе своей истории» // «История государства и права», 2006, N 7)

- ^ Красный воин (МВО). 1930. 13 февраля, 14 мая.

- ^ Kulchytskyi, S. Liquidation of kulaks as class (ЛІКВІДАЦІЯ КУРКУЛЬСТВА ЯК КЛАСУ). Encyclopedia of History of Ukraine. 2009.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Sheila (2000). "The Party Is Always Right". Everyday Stalinism: Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times: Soviet Russia in the 1930s (paperback ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 22. ISBN 9780195050011.

The Soviet regime was adept at creating its own enemies, whom it then suspected of conspiracy against the state. It did so first by declaring that all members of certain social classes and estates – primarily former nobles, members of the bourgeoisie, priests, and kulaks – were by definition 'class enemies,' resentful of their loss of privilege and likely to engage in counterrevolutionary conspiracy to recover them. The next step, taken at the end of the 1920s, was the 'liquidation as a class' of certain categories of class enemies, notably kulaks and, to a lesser extent, Nepmen and priests. This meant that the victims were expropriated, deprived of the possibility of continuing their previous way of earning a living, and often arrested and exiled.

- ^ Suslov, Andrei (July 2019). "'Dekulakization' as a Facet of Stalin's Social Revolution (The Case of Perm Region)". The Russian Review. 78 (3): 371–391. doi:10.1111/russ.12236. ISSN 1467-9434. Retrieved 21 November 2021 – via ResearchGate.

Further reading[]

- Conquest, Robert. The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror–Famine (1987)[ISBN missing]

- Figes, Orlando. The whisperers: private life in Stalin's Russia (Macmillan, 2007).[ISBN missing] detailed histories of actual Kulak families.

- Hildermeier, Manfred. Die Sowjetunion 1917–1991. (Oldenbourg Grundriss der Geschichte, Bd. 31), Oldenbourg, 2. Aufl., München 2007, ISBN 978-3-486-58327-4.

- Kaznelson, Michael. "Remembering the Soviet State: Kulak children and dekulakisation". Europe-Asia Studies 59.7 (2007): 1163–1177.

- Lewin, Moshe. "Who was the Soviet kulak?". Europe‐Asia Studies 18.2 (1966): 189–212.

- Viola, Lynne. "The Campaign to Eliminate the Kulak as a Class, Winter 1929–1930: A Reevaluation of the Legislation". Slavic Review 45.3 (1986): 503–524.

- Viola, Lynne. "The Peasants' Kulak: Social Identities and Moral Economy in the Soviet Countryside in the 1920s". Canadian Slavonic Papers 42.4 (2000): 431–460.

- Communist Party of the Soviet Union

- Human rights abuses in the Soviet Union

- Forced migration in the Soviet Union

- Mass murder in 1930

- Mass murder in 1931

- Political and cultural purges

- Political repression in the Soviet Union

- Property crimes

- Soviet phraseology