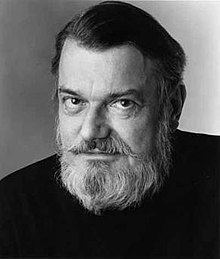

Del Close

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2018) |

Del Close | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | March 9, 1934 Manhattan, Kansas, U.S. |

| Died | March 4, 1999 (aged 64) Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Resting place | Goodman Theatre, Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Occupation | Actor, writer, teacher |

| Years active | 1960–1999 |

Del P. Close (March 9, 1934 – March 4, 1999) was an American actor, writer, and teacher who coached many of the best-known comedians and comic actors of the late twentieth century.[1] In addition to an acting career in television and film, he was a premier influence on modern improvisational theater. In 1994, Close co-authored the book Truth in Comedy: The Manual of Improvisation (with Charna Halpern and Kim Johnson),[2] which outlines techniques now common in longform improvisation and describes the overall structure of "Harold", which remains a common frame for longer improvisational scenes.[3]

Life and career[]

Early life[]

Close was born on March 9, 1934 in Manhattan, Kansas, the son of an inattentive, alcoholic father.[4] He ran away from home at the age of 17 to work in a traveling side show, but returned to attend Kansas State University. At age 19 he performed in summer stock with the Belfry Players at Lake Geneva, Wisconsin.[5] At age 23 he became a member of the Compass Players in St. Louis. When most of the cast—including Mike Nichols and Elaine May—moved to New York City, Close followed. He developed a stand-up comedy act, appeared in the Broadway musical revue The Nervous Set, and performed briefly with an improv company in Greenwich Village with fellow Compass alumni Mark and Barbara Gordon. Close also worked with John Brent to record the classic Beatnik satire album How to Speak Hip, a parody of language-learning tools that purported to teach listeners the secret language of the "hipster".[6]

Chicago years[]

In 1960 Close moved to Chicago, his home base for much of the rest of his life, to perform and direct at Second City, but was fired due to substance abuse. He spent the latter half of the 1960s in San Francisco where he was the house director of improv ensemble The Committee, featuring performers such as Gary Goodrow, Carl Gottlieb, Peter Bonerz, Howard Hesseman and Larry Hankin. He toured with the Merry Pranksters, and he created light images for Grateful Dead shows. In 1972 he returned to Chicago and to Second City. He also directed and performed for Second City's troupe in Toronto, in 1977. Over the next decade he coached many popular comedians. In the early 1980s he served as "house metaphysician" at Saturday Night Live; for many years, a significant percentage of the show's cast were Close protégés. He spent the mid-to-late 1980s and 1990s teaching improv, collaborating with Charna Halpern at Yes And Productions and the ImprovOlympic Theater with Compass Players producer, David Shepherd.[7]

In 1987, Close mounted his first scripted show, Honor Finnegan vs. the Brain of the Galaxy, created by members of Close and Halpern's Improv Olympics from a scenario by Close, at CrossCurrents in Chicago. Running concurrently at the same theater was "The TV Dinner Hour", written by Richard O'Donnell of New Age Vaudeville, featuring Close's running routine as The Rev. Thing of the First Generic Church of What's-his-name.[8]

During this period, Close also appeared in several movies; he portrayed corrupt alderman John O'Shay in The Untouchables[9] and an English teacher in Ferris Bueller's Day Off. He also co-authored the graphic horror anthology Wasteland for DC Comics with John Ostrander,[10] and co-wrote several installments of the "Munden's Bar" backup feature for Ostrander's Grimjack.

In 1993, Close performed in the World Premiere of Steve Martin's "Picasso at the Lapin Agile" at Chicago's Steppenwolf Theatre Company's Studio Theatre.

Death and legacy[]

Close died of emphysema on March 4, 1999, at the Illinois Masonic Hospital (now the Advocate Illinois Masonic Medical Center) in Chicago, five days before his 65th birthday.[1] He bequeathed his skull to Chicago's Goodman Theatre to be used in its productions of Hamlet, and specified that he be duly credited in the program as portraying Yorick. Charna Halpern, Close's long-time professional partner and the executor of his will, donated a skull—purportedly Close's—to the Goodman in a high-profile televised ceremony on July 1, 1999.[11] A front-page article in the Chicago Tribune in July 2006 questioned the authenticity of the skull, citing the presence of dentition (Close was edentulous at the time of his death) and autopsy marks (Close was not autopsied), among other problems.[12] Halpern stood by her story at the time, but admitted in a The New Yorker interview three months later that she had purchased the skull from a local medical supply company.[13][14]

Bill Murray organized an early 65th birthday party and wake, shortly before Del's anticipated death as he lay on his deathbed in a Chicago hospital, memorialized in a two-part video.[15]

After Close's death, his former students in the Upright Citizens Brigade founded the annual Del Close Marathon, three days of continuous improvisation by hundreds of performers at various venues in New York City.[16]

Notable students[]

- Dan Aykroyd

- Ike Barinholtz

- James Belushi

- John Belushi

- Matt Besser

- Stephen Burrows

- Heather Anne Campbell

- John Candy

- Jay Chandrasekhar

- Stephen Colbert

- Andy Dick

- Brian Doyle-Murray

- Rachel Dratch

- Ali Farahnakian

- Chris Farley

- Jon Favreau

- Tina Fey

- Neil Flynn

- Aaron Freeman

- Pete Gardner

- Jon Glaser

- TJ Jagodowski

- Tim Kazurinsky

- David Koechner

- Shelley Long

- Adam McKay

- Tim Meadows

- Susan Messing

- Jerry Minor

- Bill Murray

- Joel Murray

- Mike Myers

- Joey Novick

- Bob Odenkirk

- Tim O'Malley

- David Pasquesi

- Amy Poehler

- Gilda Radner

- Harold Ramis

- Andy Richter

- Ian Roberts

- Hugh Romney (Wavy Gravy)

- Mitch Rouse

- Horatio Sanz

- Amy Sedaris

- Brian Stack

- Eric Stonestreet

- Dave Thomas

- Vince Vaughn

- Matt Walsh

- Stephnie Weir

- George Wendt

The Delmonic Interviews[]

In 2002, Cesar Jaime and Jeff Pacocha produced and directed a film composed of interviews with former students, friends, and collaborators of Del Close. The film documented not only Del's life and history, but the impact he had on the people in his life and the art form he helped to create. It is not sold on DVD and was made as a thank you and a tribute to Del, "as a way to allow those that never got to meet or study with him, a chance to understand what he was like."[17]

The Delmonic Interviews includes interviews with: Charna Halpern (co-founder of Chicago's iO Theater), Matt Besser (iO's The Family; Upright Citizens Brigade), Rachel Dratch (iO; Second City; Saturday Night Live), Neil Flynn (iO's The Family; NBC's Scrubs), Susan Messing (iO; Second City; Annoyance Productions), Amy Poehler (Upright Citizens Brigade, Saturday Night Live), and (iO's The Family; Del's "Warchief"). The film was shown at several national improv festivals, including the 2004 Chicago Improv Festival, the 2004 Phoenix Improv Festival, the 2002 Del Close Marathon in New York City, and the 2006 LA Improv Festival.

Close in print[]

Close is featured in an extensive interview in Something Wonderful Right Away, a book about the members of the Compass Players and Second City written by Jeffrey Sweet. Originally published in 1978 by Avon, it is currently available from Limelight Editions.

From 1984 to 1988, Del Close wrote comic book stories in First Comics' Grimjack. With regular writer John Ostrander, Close co-wrote Munden's Bar stories in Grimjack issues #3, 4, 8, 10, 17, 22, 25, 28, 35, and 42.[18] (Close knew Ostrander from the Chicago theater scene.)[19] From 1987 to 1989, also with Ostrander, Close wrote anthology-style horror stories in the DC Comics title Wasteland. Several of the stories are allegedly autobiographical;[20][19] one recounts Close's experiences while filming Beware! The Blob (1972), and another recalls an encounter with writer L. Ron Hubbard, author of horror and science fiction, and founder of Scientology.

In 2004, writer/comedian R. O'Donnell wrote a feature entitled My Summer With Del published for Stop Smiling Magazine's Comedian Issue #17. It was an account of O'Donnell's visits at Del's Chicago apartment as well as recounting highlights of their time spent at CrossCurrents, the theater that housed both their comedy groups.[21]

In 2005, Jeff Griggs published Guru, a book detailing his friendship with Close during the last two years of Close's life. Due to Close's poor health (in part caused by long-term alcohol and drug use), Halpern suggested that Griggs run errands with Close. Guru gives a particularly detailed and complete picture of Close based on those shared hours. At the beginning of their relationship, Griggs was a student of Del's, and the book includes several chapters in which Griggs depicts Close as a teacher. The book has been adapted into a screenplay, and as of 2006 Harold Ramis was attached to direct the script.[22] Ramis (who died in 2014) wanted Bill Murray to play Close.

In 2007, Eric Spitznagel wrote an article in the September issue of The Believer magazine reflecting on Close's life and his propensity for story-telling.[23]

In 2008, Kim "Howard" Johnson's full-length biography of Close, The Funniest One in the Room: The Lives and Legends of Del Close was published. Johnson himself was a student of Close, and remained friends with Close until his death.

Filmography[]

- Goldstein (1964)

- Beware! The Blob (1972) as Hobo Wearing Eyepatch

- Gold (1972) as Hawk

- American Graffiti (1973) as Man at Bar (Guy)

- The Last Affair (1976)

- Thief (1981) as Mechanic #1

- Ferris Bueller's Day Off (1986) as English Teacher

- One More Saturday Night (1986) as Mr. Schneider / Large Tattooed Man

- Light of Day (1987) as Dr. Natterson

- The Untouchables (1987) as Alderman

- The Big Town (1987) as Deacon Daniels

- The Blob (1988) as Reverend Meeker

- Fat Man and Little Boy (1989) as Dr. Kenneth Whiteside

- Next of Kin (1989) as Frank

- Opportunity Knocks (1990) as Williamson

- The Public Eye (1992) as H.R. Rineman

- Mommy 2: Mommy's Day (1997) as Warden

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bruce Weber (March 16, 1999). "Del Close, 64, a Comedian With a Flair for Improvisation". The New York Times. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

Del Close, an actor, improvisational comic and mentor to such comedians as John Belushi, John Candy and Bill Murray, died on March 4 at Illinois Masonic Hospital in Chicago. He was 64 and lived in Chicago. ... The cause was emphysema ...

- ^ Halpern, Charna; Close, Del; Johnson, Kim (1994). Truth in Comedy: The Manual of Improvisation. Meriwether Pub. ISBN 978-1-56608-003-3.

- ^ Charna Halpern; Del Close; Kim Johnson (1994). Truth in Comedy. ISBN 978-1-56608-003-3.

- ^ "United States Social Security Death Index," index, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/J1RL-5M4 : accessed Mar 12, 2013), Del P Close, March 4, 1999.

- ^ Program, "The Belfry Players, Inc.," 1962, p. 23

- ^ "'How to Speak Hip' – Mercury Records 1959". Iotaillustration.posterous.com. January 7, 2011. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- ^ "As Del Lay Dying". April 3, 2008. Retrieved March 4, 2012.

- ^ Kogan, Rick (March 20, 1987). "Comedy Uneven in Del Close's New Show". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- ^ Johnson, Kim "Howard" (April 2008). The Funniest One in the Room: The Lives and Legends of del Close. ISBN 9781569764367.

- ^ Fryer, Kim (July 1987). "DC News". The Comics Journal. Fantagraphics Books (116): 28.

- ^ Osnos, Evan (July 7, 1999). "Even After Death, Del Close Ahead Of Acting Crowd". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 1, 2011.

- ^ Elder, RK (July 21, 2006). No bones about it: Comic got last laugh. Chicago Tribune archive. Retrieved March 7, 2013

- ^ Friend, Tad (October 9, 2006). "Skulduggery". The New Yorker. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- ^ "Skull not that of Del Close". Articles.chicagotribune.com. October 5, 2006. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- ^ Del Close's Last Birthday Party (Part 1 of 2). Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ Malinski, G (June 25, 2015). Ten improv shows at the Del Close Marathon that you should see. VillageVoice.com, retrieved September 24, 2015.

- ^ "Cesar Jaime". ImprovResourceCenter.com. Retrieved July 18, 2008.

- ^ Grand Comics Database. Accessed Sept. 28, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fiffe, Michel. "WASTELAND: The John Ostrander Interview," Factual Opinion (March 6, 2012).

- ^ Mautner, Chris, "Collect This Now! Wasteland," Comic Book Resources (Aug 17, 2009).

- ^ O'Donnell, R. (2004). "My Summer With Del". Stop Smiling magazine. Archived from the original on December 17, 2008. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- ^ "Harold Ramis interview". SuicideGirls.com. Retrieved December 17, 2006.

- ^ Spitznagel, Eric (September 2007). "Follow the Fear". The Believer. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

External links[]

- Audio Interview with Griggs on The Sound of Young America: MP3 Link

- Del Close at Improv/Comedy

- Del Close Improv Marathon

- "As Del Lay Dying," an account of Del Close's final days (w/ video)

- "Comics scripter, comedy legend Del Close dies at 64", by his biographer Kim "Howard" Johnson (in Comics Buyer's Guide, March 26, 1999, p. 8)

- Del Close at IMDb

- 1934 births

- 1999 deaths

- Male actors from Kansas

- Writers from Manhattan, Kansas

- American comics writers

- American male film actors

- American theatre directors

- Deaths from emphysema

- Disease-related deaths in Illinois

- 20th-century American male actors