Demasduit

Demasduit (c. 1796 – January 8, 1820[3]) was a Beothuk woman, one of the last of her people on the island of Newfoundland.

Biography[]

Demasduit was born near the end of the 18th century. It was once believed that the Beothuk population had been decimated by conflict with European settlers. However, the most reliable research today suggests instead that the Beothuk population was very small, between 500 and 1000 people at the time of European contact, and when European settlers arrived permanently, the Beothuk were cut off from their traditional coastal hunting grounds. Furthermore, there was no one to promote peaceful relations between the Beothuk and the settlers. As Newfoundland's population was so small, a missionary effort could not be supported, and the European governments were mainly interested in marine resources, so no agents were appointed to deal with the native population. Further contributing to the Beothuk's demise was the arrival in North America of European diseases.[4]

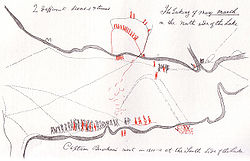

In the fall of 1818, a small group of Beothuks had captured a boat and some fishing equipment near the mouth of the Exploits River. The governor of the colony, Sir Charles Hamilton, authorized an attempt to recover the stolen property. On March 1, 1819, John Peyton Jr. and eight armed men went up the Exploits River to Red Indian Lake in search of the Beothuks and their equipment. A dozen Beothuk fled the campsite, Demasduit among them. Bogged down in the snow, she exposed her breasts, a nursing mother, begging for mercy. Nonosbawsut, her husband and the leader of the group, was killed while attempting to negotiate for Demasduit’s release. Her infant son died a few days after she was taken.[citation needed]

Peyton and his men were absolved of the murder of Nonosbawsut by a grand jury in St. John's, the judge concluding that "[there was] no malice on the part of Peyton's party to get possession of any of [the Indians] by such violence as would occasion bloodshed".[citation needed]

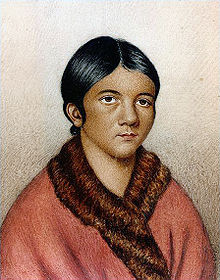

Demasduit was taken to Twillingate and for a time lived with the Anglican priest there, Rev. John Leigh. He learned that she was also called Shendoreth and Waunathoake, but he renamed her Mary March, after the Virgin Mary and the month in which she was kidnapped. Demasduit was brought to St. John's and spent much of the spring of 1819 in St. John's, brought there by Leigh and John Peyton Jr. While there, Lady Hamilton painted her portrait.[citation needed]

During the summer of 1819, a number of attempts were made to return her to her people, without success. Captain David Buchan was to go overland to Red Indian Lake with Demasduit in November, the people of St. John's and Notre Dame Bay having raised the money to return the Beothuk to her home. However, she was taken ill and died of tuberculosis at Ship Cove (now Botwood) aboard Buchan's vessel Grasshopper, on 8 January 1820. Her body was left in a coffin on the lakeshore, where it was found by members of her tribe and returned to her village in February.[5] Demasduit’s body was placed in a burial hut beside her husband and child. There were only thirty-one of the Beothuk remaining at that time.[citation needed]

Legacy[]

Demasduit's niece, a young woman named Shanawdithit (1801–1829), was the last known Beothuk.[citation needed]

The song "Demasduit Dream", recorded by Newfoundland band Great Big Sea, describes this incident.[citation needed]

The in the town of Grand Falls-Windsor, Newfoundland and Labrador, is named after her. In May 2006, a group of local grade 2 students, led by student Conor O'Driscoll, helped collect more than 500 signatures on a petition to rename the museum to Demasduit's original identity, rather than the name she was given after her capture.[6]

Genetic testing[]

In 2007, DNA testing was conducted on material from the teeth of Demasduit and her husband Nonosabasut. The results assigned them to Haplogroup X (mtDNA) and Haplogroup C (mtDNA), respectively, which are also found in current Mi'kmaq populations in Newfoundland.[7][8]

See also[]

- List of people of Newfoundland and Labrador

The novel "River Thieves" by Michael Crummey explores this part of Newfoundland history (cf).

References[]

- ^ Charlotte Gray 'The Museum Called Canada: 25 Rooms of Wonder' Random House, 2004

- ^ Mullen, Gary R., "Philip Henry Gosse," Encyclopedia of Alabama, 26 August 2008, retrieved 9 September 2011

- ^ G. M. Story. "DEMASDUWIT". University of Toronto/Université Laval. Retrieved October 2, 2013.

- ^ "Disappearance of the Beothuk". www.heritage.nf.ca. Retrieved 2019-10-21.

- ^ MacLean, John. Canadian Savage People, 1896. pp 318.

- ^ CBC News (May 31, 2006). "N.L. children petition to rename museum". CBC News. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ Kuch, M; et al. (2007). "A preliminary analysis of the DNA and diet of the extinct Beothuk: A systematic approach to ancient human DNA" (PDF). American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 132 (4): 594–604. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20536. PMID 17205549. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-02-14.

- ^ Pope, A (2011). "Mitogenomic and microsatellite variation in descendants of the founder population of Newfoundland: high genetic diversity in an historically isolated population" (PDF). Genome. 54 (2): 110–119. doi:10.1139/g10-102. PMID 21326367.

External links[]

- 1796 births

- 1820 deaths

- Beothuk people

- People from Newfoundland (island)

- Newfoundland Colony people

- 19th-century deaths from tuberculosis

- Tuberculosis deaths in Newfoundland and Labrador

- Persons of National Historic Significance (Canada)

- 19th-century indigenous people of the Americas

- Violence against Indigenous women in Canada

- Violence against Indigenous people in Canada