Dimethyl sulfide

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

(Methylsulfanyl)methane[1] | |

| Other names | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| 3DMet | |

| 1696847 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.770 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | dimethyl+sulfide |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 1164 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| Properties | |

| C2H6S | |

| Molar mass | 62.13 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Colourless liquid |

| Odor | Cabbage, sulfurous |

| Density | 0.846 g cm−3 |

| Melting point | −98 °C; −145 °F; 175 K |

| Boiling point | 35 to 41 °C; 95 to 106 °F; 308 to 314 K |

| log P | 0.977 |

| Vapor pressure | 53.7 kPa (at 20 °C) |

| −44.9⋅10−6 cm3/mol | |

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.435 |

| Thermochemistry | |

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−66.9–63.9 kJ⋅mol−1 |

Std enthalpy of

combustion (ΔcH⦵298) |

−2.1818–2.1812 MJ⋅mol−1 |

| Hazards | |

| Safety data sheet | osha.gov |

| GHS pictograms |

|

| GHS Signal word | Danger |

GHS hazard statements

|

H225, H315, H318, H335 |

| P210, P261, P280, P305+351+338 | |

| Flash point | −36 °C (−33 °F; 237 K) |

| 206 °C (403 °F; 479 K) | |

| Explosive limits | 19.7% |

| Related compounds | |

Related chalcogenides

|

Dimethyl ether (dimethyl oxide) Dimethyl selenide Dimethyl telluride |

Related compounds

|

Dimethyl ether Dimethyl sulfoxide Dimethyl sulfone |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

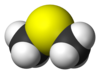

Dimethyl sulfide (DMS) or methylthiomethane is an organosulfur compound with the formula (CH3)2S. Dimethyl sulfide is a flammable liquid that boils at 37 °C (99 °F) and has a characteristic disagreeable odor. It is a component of the smell produced from cooking of certain vegetables, notably maize, cabbage, beetroot, and seafoods. It is also an indication of bacterial contamination in malt production and brewing. It is a breakdown product of dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP), and is also produced by the bacterial metabolism of methanethiol.

Natural occurrence[]

DMS originates primarily from DMSP, a major secondary metabolite in some marine algae.[2] DMS is the most abundant biological sulfur compound emitted to the atmosphere.[3][4] Emission occurs over the oceans by phytoplankton. DMS is also produced naturally by bacterial transformation of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) waste that is disposed of into sewers, where it can cause environmental odor problems.[5]

DMS is oxidized in the marine atmosphere to various sulfur-containing compounds, such as sulfur dioxide, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), dimethyl sulfone, methanesulfonic acid and sulfuric acid.[6] Among these compounds, sulfuric acid has the potential to create new aerosols which act as cloud condensation nuclei. Through this interaction with cloud formation, the massive production of atmospheric DMS over the oceans may have a significant impact on the Earth's climate.[7][8] The CLAW hypothesis suggests that in this manner DMS may play a role in planetary homeostasis.[9]

Marine phytoplankton also produce dimethyl sulfide,[10] and DMS is also produced by bacterial cleavage of extracellular DMSP.[11] DMS has been characterized as the "smell of the sea",[12] though it would be more accurate to say that DMS is a component of the smell of the sea, others being chemical derivatives of DMS, such as oxides, and yet others being algal pheromones such as dictyopterenes.[13]

Dimethyl sulfide also is an odorant emitted by kraft pulping mills, and it is a byproduct of Swern oxidation.

Dimethyl sulfide, dimethyl disulfide, and dimethyl trisulfide have been found among the volatiles given off by the fly-attracting plant known as dead-horse arum (Helicodiceros muscivorus). Those compounds are components of an odor like rotting meat, which attracts various pollinators that feed on carrion, such as many species of flies.[14]

Physiology of dimethyl sulfide[]

Dimethyl sulfide is normally present at very low levels in healthy people, namely <7nM in blood, <3 nM in urine and 0.13 – 0.65 nM on expired breath.[15][16]

At pathologically dangerous concentrations, this is known as dimethylsulfidemia. This condition is associated with blood borne halitosis and dimethylsulfiduria.[17][18][19]

In people with chronic liver disease (cirrhosis), high levels of dimethyl sulfide may be present the breath, leading to an unpleasant smell (fetor hepaticus).

Smell[]

Dimethyl sulfide has a characteristic smell commonly described as cabbage-like. It becomes highly disagreeable at even quite low concentrations. Some reports claim that DMS has a low olfactory threshold that varies from 0.02 to 0.1 ppm between different persons, but it has been suggested that the odor attributed to dimethyl sulfide may in fact be due to di- and polysulfides and thiol impurities, since the odor of dimethyl sulfide is much less disagreeable after it is freshly washed with saturated aqueous mercuric chloride.[20] Dimethyl sulfide is also available as a food additive to impart a savory flavor; in such use, its concentration is low. Beetroot,[21] asparagus,[22] cabbage, corn and seafoods produce dimethyl sulfide when cooked.

Dimethyl sulfide is also produced by marine planktonic micro-organisms such as the coccolithophores and so is one of the main components responsible for the characteristic odor of sea water aerosols, which make up a part of sea air. In the Victorian era, before DMS was discovered, the origin of sea air's 'bracing' aroma was attributed to ozone.[23]

Preparation[]

In industry dimethyl sulfide is produced by treating hydrogen sulfide with excess methanol over an aluminium oxide catalyst.[24]

Industrial uses[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2012) |

Dimethyl sulfide has been used in petroleum refining to pre-sulfide hydrodesulfurization catalysts, although other disulfides or polysulfides are preferred and easier to handle. It is used as a presulfiding agent to control the formation of coke and carbon monoxide in ethylene production. DMS is also used in a range of organic syntheses, including as a reducing agent in ozonolysis reactions. It also has a use as a food flavoring component. It can also be oxidized to dimethyl sulfoxide, (DMSO), which is an important industrial solvent.

The largest single commercial producer of DMS in the world is Gaylord Chemical Corporation.[citation needed] The Chevron Phillips Chemical company is also a major manufacturer of DMS. CP Chem produces this material at their facilities in Borger, Texas, USA and Tessenderlo, Belgium.[citation needed]

Other uses[]

Dimethyl sulfide is a Lewis base, classified as a soft ligand (see also ECW model). It forms complexes with many transition metals. It serves a displaceable ligand in chloro(dimethyl sulfide)gold(I) and other coordination compounds. Dimethyl sulfide is also used in the ozonolysis of alkenes, reducing the intermediate trioxolane and oxidizing to DMSO.

Safety[]

Dimethyl sulfide is highly flammable and an eye and skin irritant. It is harmful if swallowed. It has an unpleasant odor at even extremely low concentrations. Its ignition temperature is 205 °C.

See also[]

- Coccolithophore, a marine unicellular planktonic photosynthetic algae, producer of DMS

- Dimethylsulfoniopropionate, a parent molecule of DMS and methanethiol in the oceans

- Emiliania huxleyi, a coccolithophorid producing DMS

- Swern oxidation

- Gaia hypothesis

- Geosmin, the substance responsible for the odour of earth

- Petrichor, the earthy scent produced when rain falls on dry soil

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "CHAPTER P-6. Applications to Specific Classes of Compounds". Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry : IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book). Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry. 2014. p. 706. doi:10.1039/9781849733069-00648. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

- ^ Stefels, J.; Steinke, M.; Turner, S.; Malin, S.; Belviso, A. (2007). "Environmental constraints on the production and removal of the climatically active gas dimethylsulphide (DMS) and implications for ecosystem modelling". Biogeochemistry. 83 (1–3): 245–275. doi:10.1007/s10533-007-9091-5.

- ^ Kappler, Ulrike; Schäfer, Hendrik (2014). "Chapter 11. Transformations of Dimethylsulfide". In Peter M.H. Kroneck and Martha E. Sosa Torres (ed.). The Metal-Driven Biogeochemistry of Gaseous Compounds in the Environment. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. 14. Springer. pp. 279–313. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9269-1_11. ISBN 978-94-017-9268-4. PMID 25416398.

- ^ Simpson, D.; Winiwarter, W.; Börjesson, G.; Cinderby, S.; Ferreiro, A.; Guenther, A.; Hewitt, C. N.; Janson, R.; Khalil, M. A. K.; Owen, S.; Pierce, T. E.; Puxbaum, H.; Shearer, M.; Skiba, U.; Steinbrecher, R.; Tarrasón, L.; Öquist, M. G. (1999). "Inventorying emissions from nature in Europe". Journal of Geophysical Research. 104 (D7): 8113–8152. Bibcode:1999JGR...104.8113S. doi:10.1029/98JD02747.

- ^ Glindemann, D.; Novak, J.; Witherspoon, J. (2006). "Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) Waste Residues and Municipal Waste Water Odor by Dimethyl Sulfide (DMS): the North-East WPCP Plant of Philadelphia". Environmental Science and Technology. 40 (1): 202–207. Bibcode:2006EnST...40..202G. doi:10.1021/es051312a. PMID 16433352.

- ^ Lucas, D. D.; Prinn, R. G. (2005). "Parametric sensitivity and uncertainty analysis of dimethylsulfide oxidation in the clear-sky remote marine boundary layer" (PDF). Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 5 (6): 1505–1525. Bibcode:2005ACP.....5.1505L. doi:10.5194/acp-5-1505-2005.

- ^ Malin, G.; Turner, S. M.; Liss, P. S. (1992). "Sulfur: The plankton/climate connection". Journal of Phycology. 28 (5): 590–597. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3646.1992.00590.x. S2CID 86179536.

- ^ Gunson, J.R.; Spall, S.A.; Anderson, T.R.; Jones, A.; Totterdell, I.J.; Woodage, M.J. (1 April 2006). "Climate sensitivity to ocean dimethylsulphide emissions". Geophysical Research Letters. 33 (7): L07701. Bibcode:2006GeoRL..33.7701G. doi:10.1029/2005GL024982.

- ^ Charlson, R. J.; Lovelock, J. E.; Andreae, M. O.; Warren, S. G. (1987). "Oceanic phytoplankton, atmospheric sulphur, cloud albedo and climate". Nature. 326 (6114): 655–661. Bibcode:1987Natur.326..655C. doi:10.1038/326655a0. S2CID 4321239.

- ^ "The Climate Gas You've Never Heard Of". Oceanus Magazine.

- ^ Ledyard, KM; Dacey, JWH (1994). "Dimethylsulfide production from dimethylsulfoniopropionate by a marine bacterium". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 110: 95–103. Bibcode:1994MEPS..110...95L. doi:10.3354/meps110095.

- ^ "Cloning the smell of the seaside". University of East Anglia. 2 February 2007.

- ^ Itoh, T.; Inoue, H.; Emoto, S. (2000). "Synthesis of Dictyopterene A: Optically Active Tributylstannylcyclopropane as a Chiral Synthon". Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan. 73 (2): 409–416. doi:10.1246/bcsj.73.409. ISSN 1348-0634.

- ^ Stensmyr, M. C.; Urru, I.; Collu, I.; Celander, M.; Hansson, B. S.; Angioy, A.-M. (2002). "Rotting Smell of Dead-Horse Arum Florets". Nature. 420 (6916): 625–626. Bibcode:2002Natur.420..625S. doi:10.1038/420625a. PMID 12478279. S2CID 1001475.

- ^ Gahl, WA; Bernardini, I; Finkelstein, JD; Tangerman, A; Martin, JJ; Blom, HJ; Mullen, KD; Mudd, SH (February 1988). "Transsulfuration in an adult with hepatic methionine adenosyltransferase deficiency". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 81 (2): 390–7. doi:10.1172/JCI113331. PMC 329581. PMID 3339126.

- ^ Tangerman, A (15 October 2009). "Measurement and biological significance of the volatile sulfur compounds hydrogen sulfide, methanethiol and dimethyl sulfide in various biological matrices". Journal of Chromatography B. 877 (28): 3366–77. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.05.026. PMID 19505855.

- ^ Tangerman, A; Winkel, E. G. (September 2007). "Intra- and extra-oral halitosis: finding of a new form of extra-oral blood-borne halitosis caused by dimethyl sulphide". J. Clin. Periodontol. 34 (9): 748–55. doi:10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01116.x. PMID 17716310.

- ^ Tangerman, A; Winkel, EG (March 2008). "The portable gas chromatograph OralChroma: a method of choice to detect oral and extra-oral halitosis". Journal of Breath Research. 2 (1): 017010. doi:10.1088/1752-7155/2/1/017010. PMID 21386154.

- ^ Tangerman, A; Winkel, EG (2 March 2010). "Extra-oral halitosis: an overview". Journal of Breath Research. 4 (1): 017003. Bibcode:2010JBR.....4a7003T. doi:10.1088/1752-7155/4/1/017003. PMID 21386205.

- ^ Morton, T. H. (2000). "Archiving Odors". In Bhushan, N.; Rosenfeld, S. (eds.). Of Molecules and Mind. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 205–216.

- ^ Parliment, T. H.; Kolor, M. G.; Maing, I. Y. (1977). "Identification of the Major Volatile Components of Cooked Beets". Journal of Food Science. 42 (6): 1592–1593. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1977.tb08434.x.

- ^ Ulrich, Detlef; Hoberg, Edelgard; Bittner, Thomas; Engewald, Werner; Meilchen, Kathrin (2001). "Contribution of volatile compounds to the flavor of cooked asparagus". Eur Food Res Technol. 213 (3): 200–204=. doi:10.1007/s002170100349. S2CID 95248775.

- ^ Highfield, Roger (2 February 2007). "Secrets of 'bracing' sea air bottled by scientists". Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ Roy, Kathrin-Maria (15 June 2000). "Thiols and Organic Sulfides". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. p. 8. doi:10.1002/14356007.a26_767. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dimethyl sulfide. |

- Climate

- Thioethers

- Foul-smelling chemicals