Dithiolane

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Dithiolane

| |||

| Other names

1,2-Dithiolane, 1,3-dithiolane

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

| |||

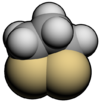

3D model (JSmol)

|

| ||

| ChEBI |

| ||

| ChemSpider |

| ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII |

| ||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C3H6S2 | |||

| Molar mass | 106.20 g·mol−1 | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related compounds

|

Ethane-1,2-dithiol | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| Infobox references | |||

A dithiolane is a sulfur heterocycle derived from cyclopentane by replacing two methylene bridges (-CH

2- units) with thioether groups. The parent compounds are 1,2-dithiolane and 1,3-dithiolane.

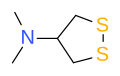

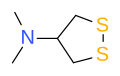

1,2-Dithiolanes are cyclic disulfides. Some dithiolanes are natural products[1] that can be found in foods, such as asparagusic acid in asparagus.[2] The 4-dimethylamino derivative nereistoxin was the inspiration for insecticides which act by blocking the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor.[3] Lipoic acid is essential for aerobic metabolism in mammals and also has strong affinity with many metals including gold, molybdenum, and tungsten.[4] Other 1,2-dithiolanes have relevance in nanomaterials such as gold nanoparticles or TMDs (MoS2 and WS2).[5][6][7]

asparagusic acid

nereistoxin, from which insecticides including cartap and bensultap were derived

lipoic acid

1,3-Dithiolanes are important as protecting groups for carbonyl compounds, since they are inert to a wide range of conditions. Reacting a carbonyl group with 1,2-ethanedithiol converts it to a 1,3-dithiolane, as detailed below.

References[]

- ^ Teuber, Lene (1990). "Naturally Occurring 1,2-Dithiolanes and 1,2,3-Trithianes. Chemical and Biological Properties". Sulfur Reports. 9 (4): 257–333. doi:10.1080/01961779008048732.

- ^ Pelchat, M. L.; Bykowski, C.; Duke, F. F.; Reed, D. R. (2011). "Excretion and perception of a characteristic odor in urine after asparagus ingestion: A psychophysical and genetic study". Chemical Senses. 36 (1): 9–17. doi:10.1093/chemse/bjq081. PMC 3002398. PMID 20876394.

- ^ Casida, John E.; Durkin, Kathleen A. (2013). "Neuroactive Insecticides: Targets, Selectivity, Resistance, and Secondary Effects". Annual Review of Entomology. 58: 99–117. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-120811-153645. PMID 23317040.

- ^ "Lipoic acid". Micronutrient Information Center, Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University, Corvallis. 1 January 2019. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ Bilewicz, Renata; Więckowska, Agnieszka; Kruszewski, Marcin; Stępkowski, Tomasz; Męczynska-Wielgosz, Sylwia; Cichowicz, Grzegorz; Piątek, Piotr; Załubiniak, Dominika; Dzwonek, Maciej (2018-04-18). "Towards potent but less toxic nanopharmaceuticals – lipoic acid bioconjugates of ultrasmall gold nanoparticles with an anticancer drug and addressing unit". RSC Advances. 8 (27): 14947–14957. doi:10.1039/C8RA01107A. ISSN 2046-2069.

- ^ Vallan, Lorenzo; Canton-Vitoria, Ruben; Gobeze, Habtom B.; Jang, Youngwoo; Arenal, Raul; Benito, Ana M.; Maser, Wolfgang K.; D’Souza, Francis; Tagmatarchis, Nikos (2018-10-17). "Interfacing Transition Metal Dichalcogenides with Carbon Nanodots for Managing Photoinduced Energy and Charge-Transfer Processes". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 140 (41): 13488–13496. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b09204. hdl:10442/16257. ISSN 0002-7863. PMID 30222336.

- ^ Tagmatarchis, Nikos; Ewels, Christopher P.; Bittencourt, Carla; Arenal, Raul; Pelaez-Fernandez, Mario; Sayed-Ahmad-Baraza, Yuman; Canton-Vitoria, Ruben (2017-06-05). "Functionalization of MoS 2 with 1,2-dithiolanes: toward donor-acceptor nanohybrids for energy conversion". NPJ 2D Materials and Applications. 1 (1): 13. doi:10.1038/s41699-017-0012-8. ISSN 2397-7132.

External links[]

Media related to Dithiolanes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dithiolanes at Wikimedia Commons- 1,3-Dithiolane Reactions

- Dithiolanes