Domus Aurea

| Domus Aurea | |

|---|---|

| Location | Regione III Isis et Serapis |

| Built in | c. 64–68 AD |

| Built by/for | Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus |

| Type of structure | Roman villa |

| Related | List of ancient monuments in Rome |

Domus Aurea | |

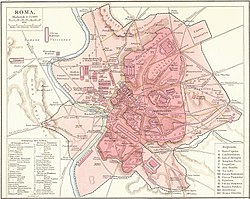

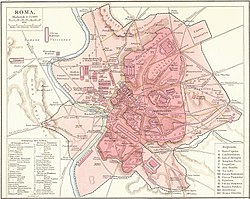

The Domus Aurea (Latin, "Golden House") was a vast landscaped complex built by the Emperor Nero largely on the Oppian Hill in the heart of ancient Rome after the great fire in 64 AD had destroyed a large part of the city.[1]

It replaced and extended his Domus Transitoria that he had built as his first palace complex on the site.[2][3]

History[]

The Domus Aurea was probably never completed.[4] Otho[5] and possibly Titus allotted money to finish at least the structure on the Oppian Hill; this continued to be inhabited, notably by emperor Vitellius in 69 but only after falling ill,[6] until it was destroyed in a fire under Trajan in 104.[7]

It was a severe embarrassment to Nero's successors as a symbol of decadence and it was stripped of its marble, jewels, and ivory within a decade.[8] Although the Oppian villa continued to be inhabited for some years, soon after Nero's death other parts of the palace and grounds, encompassing 2.6 km2 (c. 1 mi2), were filled with earth and built over: the Baths of Titus were already being built on part of the site, probably the private baths, in 79 AD.[9][10] On the site of the lake, in the middle of the palace grounds, Vespasian built the Flavian Amphitheatre, which could be reflooded at will,[11] with the Colossus Neronis beside it.[1] The Baths of Trajan,[1][12] and the Temple of Venus and Rome were also built on the site. Within 40 years, the palace was completely obliterated. Paradoxically, this ensured the wall paintings' survival by protecting them from moisture.[13][9][14]

Rediscovery[]

When a young Roman inadvertently fell through a cleft in the Esquiline hillside at the end of the 15th century, he found himself in a strange cave or grotto filled with painted figures.[8] Soon the young artists of Rome were having themselves let down on boards knotted to ropes to see for themselves.[15] The Fourth Style frescoes that were uncovered then have faded now, but the effect of these freshly rediscovered grotesque[16] decorations (Italian: grotteschi) was electrifying in the early Renaissance, which was just arriving in Rome.

When Raphael and Michelangelo crawled underground and were let down shafts to study them, the paintings were a revelation of the true world of antiquity.[17] Beside the graffiti signatures of later tourists, like Casanova and the Marquis de Sade scratched into a fresco inches apart (British Archaeology June 1999),[18] are the autographs of Domenico Ghirlandaio, Martin van Heemskerck, and Filippino Lippi.[19]

It was even claimed that various classical artworks found at this time—such as the Laocoön and his Sons and Venus Kallipygos[20]—were found within or near the Domus's remains, though this is now accepted as unlikely (high quality artworks would have been removed—to the Temple of Peace, for example—before the Domus was covered over with earth).[20]

The frescoes' effect on Renaissance artists was instant and profound (it can be seen most obviously in Raphael's decoration for the loggias in the Vatican), and the white walls, delicate swags, and bands of frieze—framed reserves containing figures or landscapes—have returned at intervals ever since, notably in late 18th century Neoclassicism,[21] making Famulus one of the most influential painters in the history of art.

20th century to present[]

Discovery of the pavilion led to the arrival of moisture starting the slow, inevitable process of decay; humidity sometimes reaches 90% inside the Domus.[17] Heavy rain was blamed for the collapse of a chunk of ceiling.[22] The presence of trees in the park above is causing further damage, as tree roots are slowly sinking into the walls, damaging the ceiling and frescoes; chemical compounds released from these roots are provoking additional deterioration.[23][10] Unfortunately, many of these trees cannot be uprooted without damaging the Domus.[24]

The sheer weight of earth on the Domus is causing a problem, as well, and architects believe that the ceiling will eventually collapse if the weight of between 2,500 and 3,000 kg/m2 is not lessened.[9] A pilot project is in the works to replace the current park above the Domus, enlarged during Mussolini's regime,[25] with a lighter roof garden planted with the type of flowers described by Pliny, Columella, and other ancient writers.[9]

Increasing concerns about the condition of the building and the safety of visitors resulted in its closing at the end of 2005 for further restoration work.[26] The complex was partially reopened on February 6, 2007, but closed on March 25, 2008 because of safety concerns.[27][17]

On March 30, 2010, 60 square metres (650 square feet) of the vault of a gallery collapsed.[14]

See also[]

- Roman architecture

- List of Roman domes

- List of ancient monuments in Rome

Notes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Roth

- ^ Andrea Carandini, Le case del potere nell'antica Roma, Roma-Bari, Laterza, 2010, ISBN 978-88-420-9422-7 p 251

- ^ Filippo Coarelli, Roma, Bari & Roma, Laterza, 2012 p 228

- ^ De la Croix, Horst; Tansey, Richard G.; Kirkpatrick, Diane (1991). Gardner's Art Through the Ages (9th ed.). Thomson/Wadsworth. p. 225. ISBN 0-15-503769-2.

- ^ Suetonius, Otho 7.1

- ^ Cassius Dio, LXV, 4.1.

- ^ Filippo Coarelli (2014). Rome and Environs: An Archaeological Guide. University of California Press. p. 182.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Domus Aurea: Nero's pleasure palace in Rome". www.througheternity.com. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Rome, Wanted in (2017-07-03). "Domus Aurea: A mad emperor's dream in 3D". Wanted in Rome. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Golden House of an Emperor - Archaeology Magazine". www.archaeology.org. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- ^ Br; Specktor, on; May 13, Senior Writer |; ET, 2019 06:42am. "Archaeologists Discovered a Hidden Chamber in Roman Emperor Nero's Underground Palace". Live Science. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- ^ Smithsonian magazine, October 2020

- ^ "Secret 'Room of the Sphinx' discovered 2,000 years later in Nero's Golden Palace". The Japan Times Online. 2019-05-11. ISSN 0447-5763. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- ^ Jump up to: a b theintrepidguide (2016-09-23). "Domus Aurea Rome: Visit Rome's Secret Hidden Palace". The Intrepid Guide. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- ^ "The Mysterious Hidden Ruins Near the Colosseum | Rome Blog". Roma Experience. 2018-05-22. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- ^ Because of their underground origin, these works were referred to as grotteschi, ("belonging to caves") and their strangeness changed the meaning of the word.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Nero's buried golden palace to open to the public - in hard hats". Reuters. 2014-10-24. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- ^ "The buried pleasure palace loved by Michelangelo and Raphael | Art | Agenda". Phaidon. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- ^ Mueller, Tom (April 1997). "Underground Rome". The Atlantic. 279 (4): 48–53. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "19th Century Grand Tour Italian Bronze of the 'Callypygian Venus' - LAPADA". lapada.org. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- ^ Alex; Turney, ra; Rome, ContributorWriter in (2017-03-18). "The Domus Aurea in Rome: 5 Reasons to Visit Nero's Palace". HuffPost. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- ^ Romey (see sources)

- ^ Donati, Silvia (2014-06-19). "Rome's Domus Aurea Needs Four-Year Restoration". ITALY Magazine. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- ^ Rome, Wanted in (2019-04-13). "Nero's first palace opens to the public in Rome". Wanted in Rome. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- ^ Cox, Cheryl (2016-02-01). "The Underground World of the Domus Aurea". planet gusto. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- ^ "Domus Aurea". World Monuments Fund. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- ^ "Rome's Domus Aurea Reopens after Six-Year Restoration". artnet News. 2014-10-27. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

Sources[]

- Ball, Larry F. (2003). The Domus Aurea and the Roman architectural revolution. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-82251-3.

- Boethius, Axel (1960). The Golden House of Nero. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan.

- Claridge, Amanda (1998). Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide. New York: Oxford University. ISBN 0-19-288003-9.

- Palmer, Alasdair (1999-07-11). "Nero's pleasure dome". London Sunday Times.

- Romey, Kristin M. (July–August 2001). "The Rain in Rome". Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America. 54 (4): 20. ISSN 0003-8113. Retrieved 2007-02-12.

- Roth, Leland M. (1993). Understanding Architecture: Its Elements, History and Meaning (First ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press. pp. 227–8. ISBN 0-06-430158-3.

- Pliny, C. Secundus (c. 77). Natural History.

- Richardson, Lawrence (1992). A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-4300-6.

- Segala, Elisabetta; Ida Sciortino (1999). Domus Aurea. Milan: Electa. ISBN 88-435-7164-8.

- Spartianus, Aelius (117-284). Historia Augusta: The Life of Hadrian.

- Warden, P.G. (1981). "The Domus Aurea Reconsidered". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 40 (4): 271–278. doi:10.2307/989644. JSTOR 989644.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Domus Aurea. |

- Great Buildings on-line: Domus Aurea

- Virtual reconstruction in 3D of the Domus Aurea

Coordinates: 41°53′29″N 12°29′43″E / 41.89139°N 12.49528°E

- 68

- Houses completed in the 1st century

- Julio-Claudian dynasty

- Ancient palaces in Rome

- Nero

- Rome R. I Monti

- National museums of Italy

- Demolished buildings and structures in Rome