Dragon robe

Dragon robes (simplified Chinese: 袞龙袍; traditional Chinese: 袞龍袍; pinyin: gǔn lóng páo; hangul: 곤룡포) were the everyday dress of the emperors or kings of China (since the Tang dynasty), Korea (Goryeo and Joseon dynasties), Vietnam (Nguyễn dynasty) and the Ryukyu Kingdom.

China[]

Chinese dragons have origins in ancient China.[1] The early use of dragon symbols on imperial robes was documented in the Book of Changes.[2] Based on the circular-collar robe, the dragon robe was first adopted by the Tang dynasty (618–906 CE);[3][4] the circular-collar robe was embellished with dragons to symbolize imperial power.[1][5][6] It was documented during the reign of Wu Zetian in 694 AD that she would bestow these robes decorated with dragons-with-three-claws to high ranking officials, i.e. court officials above the third rank, and to princes.[1][6] The dragon robes were a symbol of power, and it was a great honour to be bestowed dragon robes by the emperor.[1] This practice continued until the Song dynasty.[4] The Song dynasty eventually made the dragon into the symbol of the emperor.[7]

Liao dynasty[]

The rulers of the Liao dynasty also used dragon roundels on their robes; currently, the oldest archeological artefacts of the dragon robe which has been found so far is dated to the Liao dynasty.[6][8]

Western Xia dynasty[]

The rulers of the Western Xia also wore a dragon robe with a belt; it was a round-collared gown decorated with dragon roundels.[6][9]

Jin dynasty[]

The Jurchen-led Jin dynasty also adopted dragon round roundels on clothing to indicate social status.[6]

Yuan dynasty[]

The Yuan dynasty was the first to codify the use of dragon robes as emblems on court robes.[5] The Imperial family of Yuan used the five-clawed long dragons, which were chasing flaming pearls among clouds.[6] Dragons with three claws were used for general occasions.[8]

Ming dynasty[]

As a result of the use of Dragon robes in the Yuan, the subsequent Ming emperors shunned them on formal occasions.[5] The dragon had five claws in the Ming.[8] Though only royals could wear dragons, honoured officials could be granted the privilege of wearing "python robes" (蟒袍 or 蟒衣) or "mang robe", which resembled dragons, only with four claws instead of five; and other dragon-looking creatures such as the "feiyu" ("Flying-fish", a creature with four claws, fin-like wings on the torso, and a fish-looking tail) and the douniu (Dipper capricorn; a creature which can have 3 or 4 claws; water buffalo-like horns).[1][10] The mang, feiyu and douniu robes were later strictly regulated by the Ming court.[1]

In the early Ming, the Ming court retained the decorative schemes of the Yuan dynasty for their own dragon robes; however, Ming designers also modified the Yuan dynasty's dragon robe and personalized it by adding "waves breaking against rocks along the lower edges of the decorative areas".[6] The Ming dynasty's dragon robe had a large dragon on the back and chest area of the robe and dragons which were placed horizontally on the skirt, wide sleeves.[11]

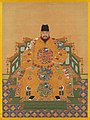

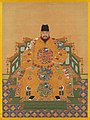

The dragon robe for daily wear of Ming dynasty

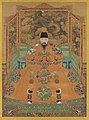

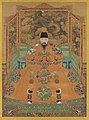

The dragon robe for special occations of Ming dynasty

Qing dynasty[]

The Qing dynasty inherited the dragon robes of the Ming dynasty.[6] The early Manchus originally did not have their own cloth or textiles, and the Manchus had to obtain Ming dragon robes and cloth when they paid tribute to the Ming dynasty or traded with the Ming.[11]

At the time of Hong Taiji, the first emperor of Qing did not want to be solely dressed in the clothing of the Han Chinese and wanted to maintain the Manchu ethnic identity, even in terms of clothing.[6][11] He also rejected the use of Twelve Ancient Symbols of Imperial Authority which used to adorn the ceremonial and ritual robes of the previous Chinese emperors since the Zhou dynasty.[6] The Ming dynasty dragon robes were therefore modified, cut and tailored to be narrow at the sleeves and waist with slits in the skirt to make it suitable for falconry, horse riding and archery.[7][11] The Ming dynasty dragon robes were simply modified and changed by Manchus to fit their Manchu tastes by cutting it at the sleeves and waist to make them narrow around the arms and waist instead of wide and added a new narrow cuff to the sleeves.[11][12] The new cuff was made out of fur. The robe's jacket waist had a new strip of scrap cloth put on the waist while the waist was made snug by pleating the top of the skirt on the robe.[13] The Manchus added sable fur skirts, cuffs and collars to Ming dragon robes and trimming sable fur all over them before wearing them.[14]

By the end of the seventeenth century AD, the Qing court decided to re-design the dragon robes of the Ming dynasty, and from the early eighteenth century, the Qing court has established a dragon robe with 9 dragons, wherein 4 dragons would radiate from the neck on the chest, back and shoulders to symbolize the cardinal direction, 4 dragons were found on the skirts - 2 on the back and 2 on the front of the skirt respectively, with the last dragon (9th) hidden placed on the inner flap of the gown.[6] In the 1730s, the Qianlong emperor started to wear the sun and moon symbols; both were part of Twelve Ancient Symbols of Imperial Authority.[6] Through the Huangchao liqi tushi decree, all the Twelve Ancient Symbols of Imperial Authority (which were ironically initially rejected by the first Qing Emperor) were eventually added on the Emperor's dragon robes by the year 1759.[6] According to the Huangchao liqi tushi, Emperor Qianlong's winter court robe worn on the day court audience was bright yellow; it was decorated with the twelve symbols and was decorated with green ocean dragons on the sleeves and collar, the skirt had five moving dragons, the lapel was decorated by one dragon and the pleats had nine dragons; the skirt has two dragons and four moving dragons and the broad collar has two moving dragons and the each sleeve cuffs have 1 dragon.[15] The use of the five-clawed dragons were also restricted to the usage of the imperial family, i.e. the emperors, the emperor's sons, and the princes of the first and second ranks.[7] Minghuang (bright yellow) dragon robes was only worn by the emperor and the empress; the sons of the Qing emperors were allowed to wear other shades of yellow, i.e. "apricot yellow" for the Crown prince, "golden yellow" for the imperial princes and for the other wives of the Emperor, and the other princes and members of the Aisin Gioro clan had to wear blue or blue-black robes.[7][16]

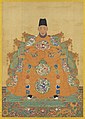

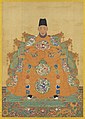

The dragon robe for special occations of Qing dynasty

Han Chinese court costume was modified by Manchus by adding a ceremonial big collar (da-ling) or shawl collar (pijian-ling).[17] It was mistakenly thought that the hunting ancestors of the Manchus skin clothes became Qing dynasty clothing, due to the contrast between Ming dynasty clothes unshaped cloth's straight length contrasting to the odd-shaped pieces of Qing dynasty longpao (i.e. "dragon robe") and chaofu (i.e. "audience robe").[18] Scholars from the west wrongly thought they were purely Manchu as the early Manchu rulers wrote several edicts stressing on maintaining their traditions and clothing.[18] Chaofu robes from Ming dynasty tombs like the Wanli emperor's tomb were excavated and it was found that Qing chaofu was similar and derived from it. They had embroidered or woven dragon-like creatures on them but are different from longpao dragon robes which are a separate clothing.[18] As they have dragon-looking creature on them, those clothing are considered "dragon robe".[18] Flared skirt with right side fastenings and fitted bodices dragon robes have been found[18] in Beijing, Shanxi, Jiangxi, Jiangsu and Shandong tombs of Ming officials and Ming imperial family members. Integral upper sleeves of Ming chaofu had two pieces of cloth attached on Qing chaofu just like earlier Ming chaofu that had sleeve extensions with another piece of cloth attached to the bodice's integral upper sleeve.

Another type of separate Qing clothing, the longpao resembles Yuan dynasty clothing like robes found in the Shandong tomb of Li Youan during the Yuan dynasty. The Qing dynasty chaofu appear in official formal portraits while Ming dynasty Chaofu that they derive from do not, perhaps indicating the Ming officials and imperial family wore chao fu under their formal robes since they appear in Ming tombs but not portraits. Qing longpao were similar unofficial clothing during the Qing dynasty.[19] The Yuan robes had hems flared and around the arms and torso they were tight. Qing unofficial clothes, longpao, derived from Yuan dynasty clothing while Qing official clothing, chaofu, derived from unofficial Ming dynasty clothing, dragon robes. The Ming consciously modelled their clothing after that of earlier Han Chinese dynasties like the Song dynasty, Tang dynasty and Han dynasty.[20]

In Japan's Nara city, the Todaiji temple's Shosoin repository has 30 short coats (hanpi) from Tang dynasty China. Ming dragon robes derive from these Tang dynasty hanpi in construction. The hanpi skirt and bodice are made of different cloth with different patterns on them and this is where the Qing chaofu originated.[20] Cross-over closures are present in both the hanpi and Ming garments. The eighth century Shosoin hanpi's variety show it was in vogue at the tine and most likely derived from much more ancient clothing. Han dynasty and Jin dynasty (266–420) era tombs in , to the Tianshan mountains south in Xinjiang have clothes resembling the Qing long pao and Tang dynasty hanpi. The evidence from excavated tombs indicates that China had a long tradition of garments that led to the Qing chaofu, and it was not invented or introduced by Manchus in the Qing dynasty or Mongols in the Yuan dynasty. The Ming robes that the Qing chao fu derived from were just not used in portraits and official paintings but were deemed as high status to be buried in tombs. In some cases the Qing went further than the Ming dynasty in imitating ancient China to display legitimacy with resurrecting ancient Chinese rituals to claim the Mandate of Heaven after studying Chinese classics. Qing sacrificial ritual vessels deliberately resemble ancient Chinese ones even more than Ming vessels.[21] Tungusic people on the Amur river like Udeghe, Ulchi and Nanai adopted Chinese influences in their religion and clothing with Chinese dragons on ceremonial robes, scroll and spiral bird and monster mask designs, Chinese New Year, using silk and cotton, iron cooking pots, and heated house from China.[22]

The Spencer Museum of Art has six longpao robes that belonged to Han Chinese nobility of the Qing dynasty.[23] Ranked officials and Han Chinese nobles had two slits in the skirts while Manchu nobles and the Imperial family had 4 slits in skirts. All first, second and third rank officials as well as Han Chinese and Manchu nobles were entitled to wear 9 dragons by the Qing Illustrated Precedents. Qing sumptuary laws only allowed four clawed dragons for officials, Han Chinese nobles and Manchu nobles while the Qing Imperial family, emperor and princes up to the second degree and their female family members were entitled to wear five clawed dragons. However officials violated these laws all the time and wore 5 clawed dragons and the Spencer Museum's 6 longpao worn by Han Chinese nobles have 5 clawed dragons on them.[24]

Tibet[]

The Qing Emperor also bestowed five-clawed dragon robes to the Dalai Lama, the Panchen lama, and the Jebtsundamba khutukhtu of Urga, which were the three most prominent dignitaries of Tibetan Buddhism.[7] Court robes were often sent from China to Tibet in the 18th century where they were redesigned in the clothing style worn by lay aristocrats; these Chinese textiles held great value in Tibet at that time as some of these aristocratic chuba could be re-sewn from many different pieces of robes.[25] Only nobles and high lamas were allowed to wear dragon robes in Tibet.[7]

Chuba (dragon robe) made in Tibet

Lay Aristocrat's Robe (Chuba)18th–19th century, Tibet.

Mongol tribes[]

The Qing emperors bestowed dragons robes on Mongol nobles who were under Qing dynasty control.[7]

Korea[]

Korean kingdoms of Silla and Balhae first adopted the circular-collar robe, dallyeong, from Tang dynasty of China in the North-South States Period for use as formal attires for royalty and government officials.

The Kings of Goryeo dynasty initially used yellow dragon robes, sharing similar clothing style as the Chinese.[26] After Goryeo was subjugated by the Yuan dynasty of China (1271-1368 AD), the Goryeo kings, the royal court, and the government had several titles and privileges downgraded to the point that they were no more the equals of the Yuan emperors.[27] The Goryeo kings were themselves demoted from the traditional status of imperial ruler of a kingdoms to the status of a lower rank king of a vassal state;[27][28] as such they were forbidden from wearing the yellow dragon robes as it was reserved for the Yuan emperors.[26] At that time, they had to wear a purple robe instead of a yellow one.[26] Goryeo kings at that time sometimes used the Mongol attire instead; several Mongol clothing elements were adopted in the clothing of Goryeo.[26] After the fall of Yuan dynasty in 1368, the rulers of Goryeo finally got the chance to regain their former Pre-Yuan dynasty status.[28] However, Goryeo was soon replaced by the Joseon dynasty in 1392.

King Wang Geon of Goryeo Dynasty, r.918 to 943 AD.

King Gongmin of Goryeo, r. 1351-1374 AD.

Joseon dynasty once again adopted the style from Ming dynasty of China, then known in China as hwangnyongpo (hangul: 황룡포; hanja: 黃龍袍), as gonryongpo. It was introduced for the first time in 1444 from the Ming dynasty during the reign of King Sejong.[29] Joseon dynasty ideologically submitted itself to Ming dynasty of China as a tributary state, and thus used red goryeonpo was used in accordance to China's policy of wearing clothing which were two levels lower.[30] The red goryeongpo was used instead of yellow for its dragon robes, as yellow symbolized the emperor and red symbolized the king.[30] After the fall of the Ming dynasty, the robe became a Korean custom by integrating unique Korean style into its design.[29] It is only when Emperor Gojong proclaimed himself as Emperor in 1897 that the colour of the goryeopo changed from red to yellow to be of the same colour as the Emperor of China.[29] Only Emperor Gojong and Emperor Sunjong were able to wear the yellow goryeonpo.[30]

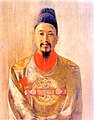

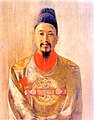

Taejo of Joseon's Gonryongpo

Yeongjo of Joseon's Gonryongpo

Gojong of the Korean Empire's Gonryongpo

Gonryongpo Dragon robe of the king

There was normally a dragon embroidered in a circle on gonryongpos. When a king or other member of the royal family wore a gonryongpo, they also wore an (익선관, 翼善冠) (a kind of hat), a jade belt, and (목화, 木靴) shoes. They wore hanbok under gonryongpo. During the winter months, a fabric of red silk was used, and gauze was used during the summer. Red indicated strong vitality.

Gonryongpos have different grades divided by their color and belt material and a Mandarin square reflecting the wearer's status. The king wore scarlet gonryongpos, and the crown prince and the eldest son of the crown prince wore dark blue ones. The belts were also divided into two kinds: jade and crystal. As for the circular, embroidered dragon design of the Mandarin square, the king wore an ohjoeryongbo (오조룡보, 五爪龍補)--a dragon with 5 toes—the crown prince wore a sajoeryongbo (사조룡보, 四爪龍補)--a dragon with 4 toes—and the eldest son of the crown prince wore a samjoeryongbo (삼조룡보, 三爪龍補)--a dragon with three toes.[31]

Vietnam[]

It is a casual dress worn by emperors of the Nguyễn dynasty.

Ryukyu[]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Shigeki, Kawakami (1998). "Imperial dragons". Kyoto National Museum. Retrieved 2021-03-19.

- ^ "Shang Shu : Yu Shu : Yi and Ji - Chinese Text Project". ctext.org (in Chinese). Retrieved 2021-03-19.

- ^ Lee, Tae-ok. Cho, Woo-hyun. Study on Danryung structure. Proceedings of the Korea Society of Costume Conference. 2003. pp.49-49.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bates, Roy (2007). All about Chinese dragons. Beijing: China History Press. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-1-4357-0322-3. OCLC 680519778.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Valery M. Garrett, Chinese Clothing: An Illustrated Guide (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), p. 7. (cited in Volpp, Sophie (June 2005). "The Gift of a Python Robe: The Circulation of Objects in "Jin Ping Mei"". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 65 (1): 133–158. doi:10.2307/25066765. JSTOR 25066765.)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m Vollmer, John E. (2007). Dressed to rule : 18th century court attire in the Mactaggart Art Collection. Mactaggart Art Collection. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press. pp. 33–37. ISBN 978-1-55195-705-0. OCLC 680510577.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Rawski, Evelyn Sakakida (1998). The last emperors : a social history of Qing imperial institutions. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 42–43. ISBN 0-520-21289-4. OCLC 37801358.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Zhao, Feng (2015). Lu, Yongxiang (ed.). A History of Chinese Science and Technology. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 391–392. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-44166-4. ISBN 978-3-662-44165-7.

- ^ Zhu, Ruixi; 朱瑞熙 (2016). A social history of middle-period China : the Song, Liao, Western Xia and Jin dynasties. Bangwei Zhang, Fusheng Liu, Chongbang Cai, Zengyu Wang, Peter Ditmanson, Bang Qian Zhu. Cambridge, United Kingdom. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-107-16786-5. OCLC 953576345.

- ^ Volpp, Sophie (June 2005). "The Gift of a Python Robe: The Circulation of Objects in "Jin Ping Mei"". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 65 (1): 133–158. doi:10.2307/25066765. JSTOR 25066765.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Keliher, Macabe (2019). The Board of Rites and the Making of Qing China. Univ of California Press. p. 157-159, 162. ISBN 978-0520300293.

- ^ Keliher, Macabe (2019). The Board of Rites and the Making of Qing China. Univ of California Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-0520300293.

- ^ Keliher, Macabe (2019). The Board of Rites and the Making of Qing China. Univ of California Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-0520300293.

- ^ Schlesinger, Jonathan (2017). A World Trimmed with Fur: Wild Things, Pristine Places, and the Natural Fringes of Qing Rule. Stanford University Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-1503600683.

- ^ Keliher, Macabe (2019). The Board of Rites and the making of Qing China. Oakland, California. pp. 166–167. ISBN 978-0-520-30029-3. OCLC 1090280665.

- ^ Shigeki, Kawakami. "Lucky Motifs on a Dragon Robe". Kyoto National Museum. Melissa M. Rinne (trans). Retrieved 2021-03-19.

- ^ Chung, Young Yang Chung (2005). Silken threads: a history of embroidery in China, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam (illustrated ed.). Harry N. Abrams. p. 148. ISBN 9780810943308. Retrieved Dec 4, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Dusenbury, Mary M.; Bier, Carol (2004). Helen Foresman Spencer Museum of Art (ed.). Flowers, Dragons & Pine Trees: Asian Textiles in the Spencer Museum of Art (illustrated ed.). Hudson Hills. p. 103. ISBN 1555952380.

- ^ Dusenbury, Mary M.; Bier, Carol (2004). Helen Foresman Spencer Museum of Art (ed.). Flowers, Dragons & Pine Trees: Asian Textiles in the Spencer Museum of Art (illustrated ed.). Hudson Hills. p. 104. ISBN 1555952380.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dusenbury, Mary M.; Bier, Carol (2004). Helen Foresman Spencer Museum of Art (ed.). Flowers, Dragons & Pine Trees: Asian Textiles in the Spencer Museum of Art (illustrated ed.). Hudson Hills. p. 105. ISBN 1555952380.

- ^ Dusenbury, Mary M.; Bier, Carol (2004). Helen Foresman Spencer Museum of Art (ed.). Flowers, Dragons & Pine Trees: Asian Textiles in the Spencer Museum of Art (illustrated ed.). Hudson Hills. p. 106. ISBN 1555952380.

- ^ Forsyth, James (1994). A History of the Peoples of Siberia: Russia's North Asian Colony 1581-1990 (illustrated, reprint, revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 214. ISBN 0521477719.

- ^ Dusenbury, Mary M.; Bier, Carol (2004). Helen Foresman Spencer Museum of Art (ed.). Flowers, Dragons & Pine Trees: Asian Textiles in the Spencer Museum of Art (illustrated ed.). Hudson Hills. p. 115. ISBN 1555952380.

- ^ Dusenbury, Mary M.; Bier, Carol (2004). Helen Foresman Spencer Museum of Art (ed.). Flowers, Dragons & Pine Trees: Asian Textiles in the Spencer Museum of Art (illustrated ed.). Hudson Hills. p. 117. ISBN 1555952380.

- ^ "Robe for Tibetan aristocrat (chuba) 18th century". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2021-03-31.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Park, Hyunhee (2021). Soju A Global History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 123���124. ISBN 9781108842013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kim, Jinwung (2012). A history of Korea : from "Land of the Morning Calm" to states in conflict. Bloomington, Indiana. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-253-00078-1. OCLC 826449509.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bauer, Susan Wise (2013). The history of the Renaissance world : from the rediscovery of Aristotle to the conquest of Constantinople (1 ed.). New York. p. 565. ISBN 978-0-393-05976-2. OCLC 846490399.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Cultural Heritage Administration. "King's Robe with Dragon Insignia - Heritage Search". Cultural Heritage Administration - English Site. Retrieved 2021-07-14.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hwang, Oak Soh (2013-06-30). "Study on the Korean Traditional Dyeing : Unique features and understanding" (PDF). International Journal of Costume and Fashion. 13 (1): 35–47. doi:10.7233/ijcf.2013.13.1.035. ISSN 2233-9051.

- ^ (in Korean) Hanbok's rebirth Archived 2012-04-25 at the Wayback Machine Kim Min-ja,《Koreana》No.22(Number 2)

- Gonryongpo[dead link] Global Encyclopedia / Daum

- Chinese traditional clothing

- Korean clothing