Earliest known life forms

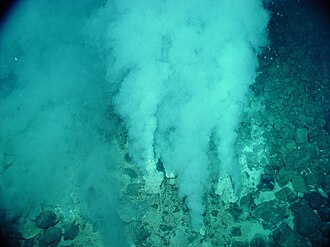

The earliest known life forms on Earth are putative fossilized microorganisms found in hydrothermal vent precipitates, considered to be about 3.42 billion years old.[1][2] The earliest time that life forms first appeared on Earth is at least 3.77 billion years ago, possibly as early as 4.28 billion years,[2] or even 4.41 billion years[4][5]—not long after the oceans formed 4.5 billion years ago, and after the formation of the Earth 4.54 billion years ago.[2][3][6][7] The earliest direct evidence of life on Earth are microfossils of microorganisms permineralized in 3.465-billion-year-old Australian Apex chert rocks.[8][9]

Biosphere

Earth remains the only place in the universe known to harbor life.[10][11] The Earth's biosphere extends down to at least 19 km (12 mi) below the surface,[12][13][14][15] and up to at least 76 km (47 mi)[16] into the atmosphere,[17][18][19] and includes soil, hydrothermal vents, and rock.[20][21] Further, the biosphere has been found to extend at least 914.4 m (3,000 ft; 0.5682 mi) below the ice of Antarctica,[22][23][24] and includes the deepest parts of the ocean,[25][26][27] down to rocks kilometers below the sea floor.[26][28][29] In July 2020, marine biologists reported that aerobic microorganisms (mainly), in "quasi-suspended animation", were found in organically-poor sediments, up to 101.5 million years old, 76.2 m (250 ft) below the seafloor in the South Pacific Gyre (SPG) ("the deadest spot in the ocean"), and could be the longest-living life forms ever found.[30][31] Under certain test conditions, life forms have been observed to survive in the vacuum of outer space.[32][33] More recently, in August 2020, bacteria were found to survive for three years in outer space, according to studies conducted on the International Space Station.[34][35] The total mass of the biosphere has been estimated to be as much as 4 trillion tons of carbon.[36] According to one researcher, "You can find microbes everywhere – [they are] extremely adaptable to conditions, and survive wherever they are."[26]

Of all species of life forms that ever lived on Earth, over five billion,[37] more than 99%, are estimated to be extinct.[38][39] Some estimates on the number of Earth's current species range from 10 million to 14 million,[40] of which about 1.2 million have been documented and over 86 percent remain undescribed.[41] However, a May 2016 scientific report estimates 1 trillion species currently on Earth, with only one-thousandth of one percent described.[42] Additionally, there are an estimated 10 nonillion (10 to the 31st power) individual viruses (including the related virions) on Earth, the most numerous type of biological entity,[43] and which some biologists consider to be life forms.[44] Moreover, there are more individual viruses than all the estimated stars in the universe;[45] which, in turn, are considered to be more numerous than all the grains of beach sand on planet Earth.[46] About 200 virus types are known to cause diseases in humans.[45][47] Other possible virus-like forms, some pathogenic, less likely to be considered living, much smaller than viruses and possibly much more primitive, include viroids, virusoids, prions and nanobes.[48]

Earliest life forms

The age of the Earth is about 4.54 billion years;[49][50][51] the earliest undisputed evidence of life on Earth dates from at least 3.5 billion years ago.[52][53][54] Some computer models suggest life began as early as 4.5 billion years ago.[4][5]

A December 2017 report stated that 3.465-billion-year-old Australian Apex chert rocks once contained microorganisms, the earliest direct evidence of life on Earth.[8][9] A 2013 publication announced the discovery of microbial mat fossils in 3.48 billion-year-old sandstone in Western Australia.[55][56][57][58] Evidence of biogenic graphite,[59] and possibly stromatolites,[60][61][62] were discovered in 3.7 billion-year-old metasedimentary rocks in southwestern Greenland, and described in 2014 in the journal Nature. Potential "remains of life" were found in 4.1 billion-year-old rocks in Western Australia and described in a 2015 study.[63] In July 2021, researchers reported finding the earliest known fossil life on Earth, in the form of "putative filamentous microfossils", possibly of methanogens and/or methanotrophs, that lived about 3.42-billion-year-old in "a paleo-subseafloor hydrothermal vein system of the Barberton greenstone belt in South Africa."[1][64]

By comparing the genomes of modern organisms, it is possible to postulate the existence of a last universal common ancestor (LUCA),[67][68] for which no specific fossil evidence exists. A 2018 study from the University of Bristol, applying a molecular clock model, concluded that the LUCA may have lived 4.477 to 4.519 billion years ago, within the Hadean eon.[4][5][a] In March 2017, fossilized microorganisms (microfossils) were announced to have been discovered in hydrothermal vent precipitates from an ancient sea-bed in the Nuvvuagittuq Belt of Quebec, Canada. These may be as old as 4.28 billion years, the oldest evidence of life on Earth, suggesting "an almost instantaneous emergence of life" after ocean formation 4.41 billion years ago.[2][3][6][7] Some researchers even speculate that life may have started nearly 4.5 billion years ago.[4][5] According to biologist Stephen Blair Hedges, "If life arose relatively quickly on Earth ... then it could be common in the universe".[69][70][71] The possibility that terrestrial life forms may have been seeded from outer space has been considered.[72][73] In January 2018, a study found that 4.5 billion-year-old meteorites found on Earth contained liquid water along with prebiotic complex organic substances that may be ingredients for life.[66][74]

As for life on land, in 2019 scientists reported the discovery of a fossilized fungus, named Ourasphaira giraldae, in the Canadian Arctic, that may have grown on land a billion years ago, well before plants are thought to have been living on land.[75][76][77] In July 2018, scientists reported that the earliest life on land may have been bacteria 3.22 billion years ago.[78] In May 2017, evidence of microbial life on land may have been found in 3.48 billion-year-old geyserite in the Pilbara Craton of Western Australia.[79][80]

Extant ancient Korarchaeota

The Korarchaeota are a group of microorganisms that appear to have diverged early in the evolution of the archaea. Korarchaeota have been detected in several geographically isolated terrestrial and marine thermal environments. One species, Korarchaeum cryptofilum, has been studied in order to gain insight into the early evolution of the archaea.[81] Based on phylogenetic analysis this organism has a deep-branching archaeal lineage. Korarchaeum cryptofilum has an ultrathin filamentous morphology. Its predicted gene functions indicate the K. cryptofilum relies on a simple mode of peptide fermentation for carbon and energy and is unable to synthesize de novo purines, Coenzyme A and other cofactors. In view of the known composition of archaeal genomes, K. cryptofilum may have retained a set of cellular characteristics that represents the ancestral archaeal form.[81]

Gallery

Earliest known life forms

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Abiogenesis

- Extremophile

- Hypothetical types of biochemistry

- Oldest dated rocks

- Outline of biology

- Outline of life forms

- Timeline of the evolutionary history of life

Footnotes

- ^ LUCA is not thought to be the first life on Earth, but rather the only type of organism of its time to still have living descendants.

References

- ^ a b c Cavalazzi, Barbara; et al. (14 July 2021). "Cellular remains in a ~3.42-billion-year-old subseafloor hydrothermal environment". Science Advances. 7 (9): eabf3963. Bibcode:2021SciA....7.3963C. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abf3963. PMC 8279515. PMID 34261651.

- ^ a b c d e Dodd, Matthew S.; Papineau, Dominic; Grenne, Tor; slack, John F.; Rittner, Martin; Pirajno, Franco; O'Neil, Jonathan; Little, Crispin T. S. (2 March 2017). "Evidence for early life in Earth's oldest hydrothermal vent precipitates" (PDF). Nature. 543 (7643): 60–64. Bibcode:2017Natur.543...60D. doi:10.1038/nature21377. PMID 28252057. S2CID 2420384.

- ^ a b c Zimmer, Carl (1 March 2017). "Scientists Say Canadian Bacteria Fossils May Be Earth's Oldest". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- ^ a b c d Staff (20 August 2018). "A timescale for the origin and evolution of all of life on Earth". Phys.org. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ a b c d Betts, Holly C.; Putick, Mark N.; Clark, James W.; Williams, Tom A.; Donoghue, Philip C.J.; Pisani, Davide (20 August 2018). "Integrated genomic and fossil evidence illuminates life's early evolution and eukaryote origin". Nature. 2 (10): 1556–1562. doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0644-x. PMC 6152910. PMID 30127539.

- ^ a b Ghosh, Pallab (1 March 2017). "Earliest evidence of life on Earth 'found". BBC News. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- ^ a b Dunham, Will (1 March 2017). "Canadian bacteria-like fossils called oldest evidence of life". Reuters. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- ^ a b Tyrell, Kelly April (18 December 2017). "Oldest fossils ever found show life on Earth began before 3.5 billion years ago". University of Wisconsin–Madison. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ^ a b Schopf, J. William; Kitajima, Kouki; Spicuzza, Michael J.; Kudryavtsev, Anatolly B.; Valley, John W. (2017). "SIMS analyses of the oldest known assemblage of microfossils document their taxon-correlated carbon isotope compositions". PNAS. 115 (1): 53–58. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115...53S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1718063115. PMC 5776830. PMID 29255053.

- ^ Graham, Robert W. (February 1990). "Extraterrestrial Life in the Universe" (PDF). NASA (NASA Technical Memorandum 102363). Lewis Research Center, Cleveland, Ohio. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ^ Altermann, Wladyslaw (2009). "From Fossils to Astrobiology – A Roadmap to Fata Morgana?". In Seckbach, Joseph; Walsh, Maud (eds.). From Fossils to Astrobiology: Records of Life on Earth and the Search for Extraterrestrial Biosignatures. Cellular Origin, Life in Extreme Habitats and Astrobiology. 12. Dordrecht, the Netherlands; London: Springer Science+Business Media. p. xvii. ISBN 978-1-4020-8836-0. LCCN 2008933212.

- ^ Deep Carbon Observatory (10 December 2018). "Life in deep Earth totals 15 to 23 billion tons of carbon – hundreds of times more than humans – Deep Carbon Observatory collaborators, exploring the 'Galapagos of the deep,' add to what's known, unknown, and unknowable about Earth's most pristine ecosystem". EurekAlert!. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ Dockrill, Peter (11 December 2018). "Scientists Reveal a Massive Biosphere of Life Hidden Under Earth's Surface". Science Alert. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ Gabbatiss, Josh (11 December 2018). "Massive 'deep life' study reveals billions of tonnes of microbes living far beneath Earth's surface". The Independent. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ Klein, JoAnna (19 December 2018). "Deep Beneath Your Feet, They Live in the Octillions – The real journey to the center of the Earth has begun, and scientists are discovering subsurface microbial beings that shake up what we think we know about life". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- ^ Loeb, Abraham (4 November 2019). "Did Life from Earth Escape the Solar System Eons Ago?". Scientific American. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ^ University of Georgia (25 August 1998). "First-Ever Scientific Estimate Of Total Bacteria On Earth Shows Far Greater Numbers Than Ever Known Before". Science Daily. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- ^ Hadhazy, Adam (12 January 2015). "Life Might Thrive a Dozen Miles Beneath Earth's Surface". Astrobiology Magazine. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ Fox-Skelly, Jasmin (24 November 2015). "The Strange Beasts That Live In Solid Rock Deep Underground". BBC online. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ Suzuki, Yohey; et al. (2 April 2020). "Deep microbial proliferation at the basalt interface in 33.5–104 million-year-old oceanic crust". Communications Biology. 3 (136): 136. doi:10.1038/s42003-020-0860-1. PMC 7118141. PMID 32242062.

- ^ University of Tokyo (2 April 2020). "Discovery of life in solid rock deep beneath sea may inspire new search for life on Mars – Bacteria live in tiny clay-filled cracks in solid rock millions of years old". EurekAlert!. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ^ Simon, Matt (15 February 2021). "Scientists Accidentally Discover Strange Creatures Under a Half Mile of Ice - Researchers only drilled through an Antarctic ice shelf to sample sediment. Instead, they found animals that weren't supposed to be there". Wired. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ Griffiths, Huw J.; et al. (15 February 2021). "Breaking All the Rules: The First Recorded Hard Substrate Sessile Benthic Community Far Beneath an Antarctic Ice Shelf". Frontiers in Marine Science. 8. doi:10.3389/fmars.2021.642040.

- ^ Fox, Douglas (20 August 2014). "Lakes under the ice: Antarctica's secret garden". Nature. 512 (7514): 244–246. Bibcode:2014Natur.512..244F. doi:10.1038/512244a. PMID 25143097.

- ^ "Mariana Trench". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ a b c Choi, Charles Q. (17 March 2013). "Microbes Thrive in Deepest Spot on Earth". LiveScience. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ Glud, Ronnie; Wenzhöfer, Frank; Middelboe, Mathias; Oguri, Kazumasa; Turnewitsch, Robert; Canfield, Donald E.; Kitazato, Hiroshi (17 March 2013). "High rates of microbial carbon turnover in sediments in the deepest oceanic trench on Earth". Nature Geoscience. 6 (4): 284–288. Bibcode:2013NatGe...6..284G. doi:10.1038/ngeo1773.

- ^ Oskin, Becky (14 March 2013). "Intraterrestrials: Life Thrives in Ocean Floor". LiveScience. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ Morelle, Rebecca (15 December 2014). "Microbes discovered by deepest marine drill analysed". BBC News. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- ^ Wu, Katherine J. (28 July 2020). "These Microbes May Have Survived 100 Million Years Beneath the Seafloor - Rescued from their cold, cramped and nutrient-poor homes, the bacteria awoke in the lab and grew". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ Morono, Yuki; et al. (28 July 2020). "Aerobic microbial life persists in oxic marine sediment as old as 101.5 million years". Nature Communications. 11 (3626): 3626. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.3626M. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-17330-1. PMC 7387439. PMID 32724059.

- ^ Dose, K.; Bieger-Dose, A.; Dillmann, R.; Gill, M.; Kerz, O.; Klein, A.; Meinert, H.; Nawroth, T.; Risi, S.; Stridde, C. (1995). "ERA-experiment "space biochemistry"". Advances in Space Research. 16 (8): 119–129. Bibcode:1995AdSpR..16..119D. doi:10.1016/0273-1177(95)00280-R. PMID 11542696.

- ^ Horneck G.; Eschweiler, U.; Reitz, G.; Wehner, J.; Willimek, R.; Strauch, K. (1995). "Biological responses to space: results of the experiment "Exobiological Unit" of ERA on EURECA I". Adv. Space Res. 16 (8): 105–118. Bibcode:1995AdSpR..16..105H. doi:10.1016/0273-1177(95)00279-N. PMID 11542695.

- ^ Strickland, Ashley (26 August 2020). "Bacteria from Earth can survive in space and could endure the trip to Mars, according to new study". CNN News. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ Kawaguchi, Yuko; et al. (26 August 2020). "DNA Damage and Survival Time Course of Deinococcal Cell Pellets During 3 Years of Exposure to Outer Space". Frontiers in Microbiology. 11: 2050. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2020.02050. PMC 7479814. PMID 32983036. S2CID 221300151.

- ^ "The Biosphere: Diversity of Life". Aspen Global Change Institute. Basalt, CO. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ^ Kunin, W.E.; Gaston, Kevin, eds. (1996). The Biology of Rarity: Causes and consequences of rare – common differences. ISBN 978-0412633805. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ^ Stearns, Beverly Peterson; Stearns, S. C.; Stearns, Stephen C. (2000). Watching, from the Edge of Extinction. Yale University Press. p. preface x. ISBN 978-0-300-08469-6. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- ^ Novacek, Michael J. (8 November 2014). "Prehistory's Brilliant Future". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ^ G. Miller; Scott Spoolman (2012). Environmental Science – Biodiversity Is a Crucial Part of the Earth's Natural Capital. Cengage Learning. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-133-70787-5. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ^ Mora, C.; Tittensor, D.P.; Adl, S.; Simpson, A.G.; Worm, B. (23 August 2011). "How many species are there on Earth and in the ocean?". PLOS Biology. 9 (8): e1001127. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001127. PMC 3160336. PMID 21886479.

- ^ Staff (2 May 2016). "Researchers find that Earth may be home to 1 trillion species". National Science Foundation. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ^ Edwards RA, Rohwer F (June 2005). "Viral metagenomics". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 3 (6): 504–10. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1163. PMID 15886693. S2CID 8059643.

- ^ Villarreal, Luis P. (8 August 2008). "Are Viruses Alive? - Although viruses challenge our concept of what "living" means, they are vital members of the web of life". Scientific American. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ a b Wu, Katherine J. (15 April 2020). "There are more viruses than stars in the universe. Why do only some infect us? - More than a quadrillion quadrillion individual viruses exist on Earth, but most are not poised to hop into humans. Can we find the ones that are?". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ Mackie, Glen (1 February 2002). "To see the Universe in a Grain of Taranaki Sand". Swinburne University of Technology. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (26 February 2021). "The Secret Life of a Coronavirus - An oily, 100-nanometer-wide bubble of genes has killed more than two million people and reshaped the world. Scientists don't quite know what to make of it". Archived from the original on 2021-12-28. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ Staff (13 August 2019). "Difference among virus, virion, viroid, virusoid and prion". Microbiology Easy Notes. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ "Age of the Earth". United States Geological Survey. 9 July 2007. Retrieved 2006-01-10.

- ^ Dalrymple, G. Brent (2001). "The age of the Earth in the twentieth century: a problem (mostly) solved". Special Publications, Geological Society of London. 190 (1): 205–221. Bibcode:2001GSLSP.190..205D. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2001.190.01.14. S2CID 130092094.

- ^ Manhesa, Gérard; Allègre, Claude J.; Dupréa, Bernard; Hamelin, Bruno (May 1980). "Lead isotope study of basic-ultrabasic layered complexes: Speculations about the age of the earth and primitive mantle characteristics". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 47 (3): 370–382. Bibcode:1980E&PSL..47..370M. doi:10.1016/0012-821X(80)90024-2. ISSN 0012-821X.

- ^ Schopf, J. William; Kudryavtsev, Anatoliy B.; Czaja, Andrew D.; Tripathi, Abhishek B. (5 October 2007). "Evidence of Archean life: Stromatolites and microfossils". Precambrian Research. 158 (3–4): 141–155. Bibcode:2007PreR..158..141S. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2007.04.009. ISSN 0301-9268.

- ^ Schopf, J. William (29 June 2006). "Fossil evidence of Archaean life". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 361 (1470): 869–885. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1834. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 1578735. PMID 16754604.

- ^ Raven, Peter H.; Johnson, George B. (2002). Biology (6th ed.). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-07-112261-0. LCCN 2001030052. OCLC 45806501.

- ^ Borenstein, Seth (13 November 2013). "Oldest fossil found: Meet your microbial mom". Excite. Yonkers, NY: Mindspark Interactive Network. Associated Press. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ^ Pearlman, Jonathan (13 November 2013). "Oldest signs of life on Earth found". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 2014-12-15.

- ^ Noffke, Nora; Christian, Daniel; Wacey, David; Hazen, Robert M. (16 November 2013). "Microbially Induced Sedimentary Structures Recording an Ancient Ecosystem in the ca. 3.48 Billion-Year-Old Dresser Formation, Pilbara, Western Australia". Astrobiology. 13 (12): 1103–1124. Bibcode:2013AsBio..13.1103N. doi:10.1089/ast.2013.1030. ISSN 1531-1074. PMC 3870916. PMID 24205812.

- ^ Djokic, Tara; Van Kranendonk, Martin J.; Campbell, Kathleen A.; Walter, Malcolm R.; Ward, Colin R. (9 May 2017). "Earliest signs of life on land preserved in ca. 3.5 Ga hot spring deposits". Nature Communications. 8: 15263. Bibcode:2017NatCo...815263D. doi:10.1038/ncomms15263. PMC 5436104. PMID 28486437.

- ^ Ohtomo, Yoko; Kakegawa, Takeshi; Ishida, Akizumi; et al. (January 2014). "Evidence for biogenic graphite in early Archaean Isua metasedimentary rocks". Nature Geoscience. 7 (1): 25–28. Bibcode:2014NatGe...7...25O. doi:10.1038/ngeo2025. ISSN 1752-0894. S2CID 54767854.

- ^ Wade, Nicholas (31 August 2016). "World's Oldest Fossils Found in Greenland". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ a b Allwood, Abigail C. (22 September 2016). "Evidence of life in Earth's oldest rocks". Nature. 537 (7621): 500–5021. doi:10.1038/nature19429. PMID 27580031. S2CID 205250633.

- ^ a b Wei-Haas, Maya (17 October 2018). "'World's oldest fossils' may just be pretty rocks – Analysis of 3.7-billion-year-old outcrops has reignited controversy over when life on Earth began". National Geographic. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- ^ Bell, Elizabeth; Boehnke, Patrick; Harrison, T. Mark; Mao, Wendy L. (24 November 2015). "Potentially biogenic carbon preserved in a 4.1 billion-year-old zircon". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (47): 14518–14521. Bibcode:2015PNAS..11214518B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1517557112. PMC 4664351. PMID 26483481.

- ^ Schultz, Isaac (14 July 2021). "These Squiggles May Be Some of the Oldest Fossil Life on Earth - Researchers say the fossils were left by 3.42-billion-year-old microbes. They could offer clues as to what sort of life may exist on other planets". Gizmodo. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ Berera, Arjun (6 November 2017). "Space dust collisions as a planetary escape mechanism". Astrobiology. 17 (12): 1274–1282. arXiv:1711.01895. Bibcode:2017AsBio..17.1274B. doi:10.1089/ast.2017.1662. PMID 29148823. S2CID 126012488.

- ^ a b Chan, Queenie H. S. et al. (10 January 2018). "Organic matter in extraterrestrial water-bearing salt crystals". Science Advances. 4 (1, eaao3521): eaao3521. Bibcode:2018SciA....4O3521C. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aao3521. PMC 5770164. PMID 29349297.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- ^ Weiss, M.C.; Sousa, F. L.; Mrnjavac, N.; Neukirchen, S.; Roettger, M.; Nelson-Sathi, S.; Martin, W.F. (2016). "The physiology and habitat of the last universal common ancestor". Nat Microbiol. 1 (9): 16116. doi:10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.116. PMID 27562259. S2CID 2997255.

- ^ Wade, Nicholas (25 July 2016). "Meet Luca, the ancestor of all living things". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 July 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ^ Borenstein, Seth (19 October 2015). "Hints of life on what was thought to be desolate early Earth". Associated Press. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ Schouten, Lucy (20 October 2015). "When did life first emerge on Earth? Maybe a lot earlier than we thought". The Christian Science Monitor. Boston, Massachusetts: Christian Science Publishing Society. ISSN 0882-7729. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ Johnston, Ian (2 October 2017). "Life first emerged in 'warm little ponds' almost as old as the Earth itself – Charles Darwin's famous idea backed by new scientific study". The Independent. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ Steele, Edward J.; et al. (1 August 2018). "Cause of Cambrian Explosion - Terrestrial or Cosmic?". Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 136: 3–23. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ McRae, Mike (28 December 2021). "A Weird Paper Tests The Limits of Science by Claiming Octopuses Came From Space". ScienceAlert. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ Staff, Lawrence Berkeley National laboratory (10 January 2018). "Ingredients for life revealed in meteorites that fell to Earth – Study, based in part at Berkeley Lab, also suggests dwarf planet in asteroid belt may be a source of rich organic matter". AAAS – EurekAlert. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (22 May 2019). "How Did Life Arrive on Land? A Billion-Year-Old Fungus May Hold Clues – A cache of microscopic fossils from the Arctic hints that fungi reached land long before plants". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ Loron, Corentin C.; François, Camille; Rainbird, Robert H.; Turner, Elizabeth C.; Borensztajn, Stephan; Javaux, Emmanuelle J. (22 May 2019). "Early fungi from the Proterozoic era in Arctic Canada". Nature. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. 570 (7760): 232–235. Bibcode:2019Natur.570..232L. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1217-0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 31118507. S2CID 162180486.

- ^ Timmer, John (22 May 2019). "Billion-year-old fossils may be early fungus". Ars Technica. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ Homann, Martin; et al. (23 July 2018). "Microbial life and biogeochemical cycling on land 3,220 million years ago" (PDF). Nature Geoscience. 11 (9): 665–671. Bibcode:2018NatGe..11..665H. doi:10.1038/s41561-018-0190-9. S2CID 134935568.

- ^ Staff (9 May 2017). "Oldest evidence of life on land found in 3.48-billion-year-old Australian rocks". Phys.org. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ University of New South Wales (26 September 2019). "Earliest signs of life: Scientists find microbial remains in ancient rocks". EurekAlert!. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- ^ a b Elkins JG, Podar M, Graham DE, Makarova KS, Wolf Y, Randau L, Hedlund BP, Brochier-Armanet C, Kunin V, Anderson I, Lapidus A, Goltsman E, Barry K, Koonin EV, Hugenholtz P, Kyrpides N, Wanner G, Richardson P, Keller M, Stetter KO. A korarchaeal genome reveals insights into the evolution of the Archaea. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Jun 10;105(23):8102-7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801980105. Epub 2008 Jun 5. PMID 18535141; PMCID: PMC2430366

- ^ Porada H.; Ghergut J.; Bouougri El H. (2008). "Kinneyia-Type Wrinkle Structures – Critical Review And Model Of Formation". PALAIOS. 23 (2): 65–77. Bibcode:2008Palai..23...65P. doi:10.2110/palo.2006.p06-095r. S2CID 128464944.

External links

- Vitae (BioLib)

- Biota (Taxonomicon)

- Life (Systema Naturae 2000)

- Wikispecies – a free directory of life

- Google Images: Earliest known life forms

- Life in the Universe – Stephen Hawking (1996)

- Video (24:32): "Migration of Life in the Universe" on YouTube – Gary Ruvkun, 2019.

- Biological evolution

- Biology terminology

- Earliest phenomena

- Evolution

- Evolutionary biology

- Tree of life (biology)