Non-cellular life

Non-cellular life, or acellular life is life that exists without a cellular structure for at least part of its life cycle.[1] Historically, most (descriptive) definitions of life postulated that an organism must be composed of one or more cells,[2] but this is no longer considered necessary, and modern criteria allow for forms of life based on other structural arrangements.[3][4][5]

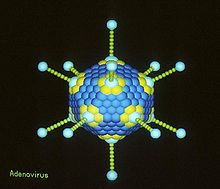

The primary candidates for non-cellular life are viruses. Some biologists consider viruses to be organisms, but others do not. Their primary objection is that no known viruses are capable of autonomous reproduction: they must rely on cells to copy them.[1][6][7][8][9]

Engineers sometimes use the term "artificial life" to refer to software and robots inspired by biological processes, but these do not satisfy any biological definition of life.

Viruses as non-cellular life[]

−4500 — – — – −4000 — – — – −3500 — – — – −3000 — – — – −2500 — – — – −2000 — – — – −1500 — – — – −1000 — – — – −500 — – — – 0 — | Flowers Birds |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(million years ago) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The nature of viruses was unclear for many years following their discovery as pathogens. They were described as poisons or toxins at first, then as "infectious proteins", but with advances in microbiology it became clear that they also possessed genetic material, a defined structure, and the ability to spontaneously assemble from their constituent parts. This spurred extensive debate as to whether they should be regarded as fundamentally, organic or inorganic — as very small biological organisms or very large biochemical molecules — and since the 1950s many scientists have thought of viruses as existing at the border between chemistry and life; a gray area between living and nonliving.[6][7][10]

Viral replication and self-assembly has implications for the study of the origin of life,[11] as it lends further credence to the hypothesis that life could have started as self-assembling organic molecules.[12][13]

Viroids[]

Viroids are the smallest infectious pathogens known to biologists, consisting solely of short strands of circular, single-stranded RNA without protein coats. They are mostly plant pathogens and some are animal pathogens, from which some are of commercial importance. Viroid genomes are extremely small in size, ranging from 246 to 467 nucleobases. In comparison, the genome of the smallest known viruses capable of causing an infection by themselves are around 2,000 nucleobases in size. Viroids are the first known representatives of a new biological realm of sub-viral pathogens.[14][15]

Viroid RNA does not code for any protein.[16] Its replication mechanism hijacks RNA polymerase II, a host cell enzyme normally associated with synthesis of messenger RNA from DNA, which instead catalyzes "rolling circle" synthesis of new RNA using the viroid's RNA as a template. Some viroids are ribozymes, having catalytic properties which allow self-cleavage and ligation of unit-size genomes from larger replication intermediates.[17]

Viroids attained significance beyond plant virology since one possible explanation of their origin is that they represent "living relics" from a hypothetical, ancient, and non-cellular RNA world before the evolution of DNA or protein.[18][19] This view was first proposed in the 1980s,[18] and regained popularity in the 2010s to explain crucial intermediate steps in the evolution of life from inanimate matter (Abiogenesis).[20][21]

Taxonomy[]

In discussing the taxonomic domains of life, the terms "Acytota" and "Aphanobionta" are occasionally used as the name of a viral kingdom, domain, or empire. The corresponding cellular life name would be Cytota. Non-cellular organisms and cellular life would be the two top-level subdivisions of life, whereby life as a whole would be known as organisms, Naturae, Biota or Vitae.[22] The taxon Cytota would include three top-level subdivisions of its own, the domains Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya.

See also[]

- Carbon chauvinism

- Hypothetical types of biochemistry

- Nanobe

- Plasmid

- Protocell

- Subviral agent

- Defective interfering particle

- Prion, an infectious protein

- Satellite, a subviral agent requiring coinfection

- Viral evolution

References[]

- ^ a b "What is Non-Cellular Life?". Wise Geek. Conjecture Corporation. 2009. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

- ^ "The 7 Characteristics of Life". infohost.nmt.edu. Archived from the original on 19 November 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ^ Benner, Steven A. (26 January 2017). "Defining Life". Astrobiology. 10 (10): 1021–1030. Bibcode:2010AsBio..10.1021B. doi:10.1089/ast.2010.0524. ISSN 1531-1074. PMC 3005285. PMID 21162682.

- ^ Trifonov, Edward (2012). "Definition of Life: Navigation through Uncertainties" (PDF). Journal of Biomolecular Structure & Dynamics. 29 (4): 647–650. doi:10.1080/073911012010525017. PMID 22208269. S2CID 8616562 – via JBSD.

- ^ Ma, Wentao (26 September 2016). "The essence of life". Biology Direct. 11 (1): 49. doi:10.1186/s13062-016-0150-5. ISSN 1745-6150. PMC 5037589. PMID 27671203.

- ^ a b Villarreal, Luis P. (December 2004). "Are Viruses Alive?". Scientific American. 291 (6): 100–105. Bibcode:2004SciAm.291f.100V. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1204-100. PMID 15597986. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ^ a b Forterre, Patrick (3 March 2010). "Defining Life: The Virus Viewpoint". Orig Life Evol Biosph. 40 (2): 151–160. Bibcode:2010OLEB...40..151F. doi:10.1007/s11084-010-9194-1. PMC 2837877. PMID 20198436.

- ^ Luketa, Stefan (2012). "New views on the megaclassification of life" (PDF). Protistology. 7 (4): 218–237.

- ^ Greenspan, Neil (28 January 2013). "Are Viruses Alive?". The Evolution & Medicine Review. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ^ Lwoff, A. (1 January 1957). "The Concept of Virus". Microbiology. 17 (2): 239–253. doi:10.1099/00221287-17-2-239. PMID 13481308.

- ^ Koonin EV; Senkevich TG; Dolja VV (2006). "The ancient Virus World and evolution of cells". Biol. Direct. 1: 29. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-1-29. PMC 1594570. PMID 16984643.

- ^ Vlassov AV; Kazakov SA; Johnston BH; Landweber LF (August 2005). "The RNA world on ice: a new scenario for the emergence of RNA information". J. Mol. Evol. 61 (2): 264–73. Bibcode:2005JMolE..61..264V. doi:10.1007/s00239-004-0362-7. PMID 16044244. S2CID 21096886.

- ^ Nussinov, Mark D.; Vladimir A. Otroshchenkob & Salvatore Santoli (1997). "Emerging Concepts of Self-organization and the Living State". Biosystems. 42 (2–3): 111–118. doi:10.1016/S0303-2647(96)01699-1. PMID 9184757.

- ^ Diener TO (August 1971). "Potato spindle tuber "virus". IV. A replicating, low molecular weight RNA". Virology. 45 (2): 411–28. doi:10.1016/0042-6822(71)90342-4. PMID 5095900.

- ^ "ARS Research Timeline – Tracking the Elusive Viroid". 2 March 2006. Retrieved 18 July 2007.

- ^ Tsagris, E. M.; Martínez De Alba, A. E.; Gozmanova, M; Kalantidis, K (2008). "Viroids". Cellular Microbiology. 10 (11): 2168–79. doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01231.x. PMID 18764915.

- ^ Daròs, J. A.; Elena, S. F.; Flores, R (2006). "Viroids: An Ariadne's thread into the RNA labyrinth". EMBO Reports. 7 (6): 593–8. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400706. PMC 1479586. PMID 16741503.

- ^ a b Diener, T. O. (1989). "Circular RNAs: Relics of precellular evolution?". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 86 (23): 9370–4. Bibcode:1989PNAS...86.9370D. doi:10.1073/pnas.86.23.9370. PMC 298497. PMID 2480600.

- ^ Villarreal, Luis P. (2005). Viruses and the evolution of life. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press. p. 31. ISBN 1-55581-309-7.

- ^ Flores, R; Gago-Zachert, S; Serra, P; Sanjuán, R; Elena, S. F. (2014). "Viroids: Survivors from the RNA world?" (PDF). Annual Review of Microbiology. 68: 395–414. doi:10.1146/annurev-micro-091313-103416. hdl:10261/107724. PMID 25002087.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (25 September 2014). "A Tiny Emissary From the Ancient Past". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ^ Witzany, G (2016). "Crucial steps to life: From chemical reactions to code using agents". Biosystems. 140: 49–57. doi:10.1016/j.biosystems.2015.12.007. PMID 26723230.

- Biological classification

- Life

- Virology

- Viruses