Elgin Marbles

| Elgin Marbles | |

|---|---|

| Parthenon Marbles | |

| |

| Artist | Phidias |

| Year | c. 447–438 BCE |

| Type | Marble |

| Dimensions | 75 m (246 ft) |

| Location | British Museum, London |

The Elgin Marbles (/ˈɛlɡɪn/),[1] also known as the Parthenon Marbles (Greek: Γλυπτά του Παρθενώνα), are a collection of Classical Greek marble sculptures made under the supervision of the architect and sculptor Phidias and his assistants. They were originally part of the temple of the Parthenon and other buildings on the Acropolis of Athens.[2][3] The collection is now on display in the British Museum, in the purpose-built Duveen Gallery.

From 1801 to 1812, agents of Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin removed about half of the surviving sculptures of the Parthenon, as well as sculptures from the Propylaea and Erechtheum.[4] The Marbles were transported by sea to Britain. Elgin later claimed to have obtained in 1801 an official decree (a firman)[5] from the Sublime Porte, the central government of the Ottoman Empire which at that time ruled Greece. This firman has not been found in the Ottoman archives despite its wealth of documents from the same period[6] and its veracity is disputed.[7] The Acropolis Museum displays a portion of the complete frieze, aligned in orientation and within sight of the Parthenon, with the position of the missing elements clearly marked and space left should they be returned to Athens.[8]

In Britain, the acquisition of the collection was supported by some,[9] while some others, such as Lord Byron, likened the Earl's actions to vandalism or looting.[10][11][12][13][14][15] Following a public debate in Parliament[16] and its subsequent exoneration of Elgin, he sold the Marbles to the British government in 1816. They were then passed into the trusteeship of the British Museum,[17] where they are now on display in the purpose-built Duveen Gallery.

After gaining its independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1832, the newly founded Greek state began a series of projects to restore its monuments and retrieve looted art. It has expressed its disapproval of Elgin's removal of the Marbles from the Acropolis and the Parthenon,[18] which is regarded as one of the world's greatest cultural monuments.[19] International efforts to repatriate the Marbles to Greece were intensified in the 1980s by then Greek Minister of Culture Melina Mercouri, and there are now many organisations actively campaigning for the Marbles' return, several united as part of the International Association for the Reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures. The Greek government itself continues to urge the return of the marbles to Athens so as to be unified with the remaining marbles and for the complete Parthenon frieze sequence to be restored, through diplomatic, political and legal means.[20]

In 2014, UNESCO offered to mediate between Greece and the United Kingdom to resolve the dispute, although this was later turned down by the British Museum on the basis that UNESCO works with government bodies, not trustees of museums.[21][22][23]

Background[]

Built in the ancient era, the Parthenon was extensively damaged by earthquakes. Also, during the Sixth Ottoman–Venetian War (1684–1699) against the Ottoman Empire, the defending Turks fortified the Acropolis and used the Parthenon as a castle. On 26 September 1687, a Venetian artillery round, fired from the Hill of Philopappus, blew up the Parthenon, and the building was partly destroyed.[24] The explosion blew out the building's central portion and caused the cella's walls to crumble into rubble.[25] Three of the four walls collapsed, or nearly so, and about three-fifths of the sculptures from the frieze fell.[26] About three hundred people were killed in the explosion, which showered marble fragments over a significant area.[27] For the next century and a half, portions of the remaining structure were scavenged for building material and looted of any remaining objects of value.[28]

Acquisition[]

In November 1798 the Earl of Elgin was appointed as "Ambassador Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary of His Britannic Majesty to the Sublime Porte of Selim III, Sultan of Turkey" (Greece was then part of the Ottoman Empire). Before his departure to take up the post he had approached officials of the British government to inquire if they would be interested in employing artists to take casts and drawings of the sculptured portions of the Parthenon. According to Lord Elgin, "the answer of the Government ... was entirely negative."[9]

Lord Elgin decided to carry out the work himself, and employed artists to take casts and drawings under the supervision of the Neapolitan court painter, Giovani Lusieri.[9] According to a Turkish local, marble sculptures that fell were being burned to obtain lime for building.[9] Although his original intention was only to document the sculptures, in 1801 Lord Elgin began to remove material from the Parthenon and its surrounding structures[29] under the supervision of Lusieri. Pieces were also removed from the Erechtheion, the Propylaia, and the Temple of Athena Nike, all inside the Acropolis.

The marbles were taken from Greece to Malta, then a British protectorate, where they remained for a number of years until they were transported to Britain.[30] The excavation and removal was completed in 1812 at a personal cost to Elgin of £74,240[9][31] (equivalent to £4,700,000 in 2019 pounds). Elgin intended to use the marbles to decorate Broomhall House, his private home near Dunfermline in Scotland,[32] but a costly divorce suit forced him to sell them to settle his debts.[33] Elgin sold the Parthenon Marbles to the British government for £35,000,[9] less than half of what it cost him to procure them, declining higher offers from other potential buyers, including Napoleon.[29]

Description[]

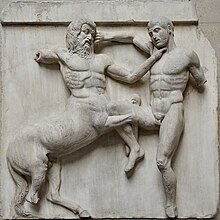

The Parthenon Marbles acquired by Elgin include some 21 figures from the statuary from the east and west pediments, 15 of an original 92 metope panels depicting battles between the Lapiths and the Centaurs, as well as 75 metres of the Parthenon Frieze which decorated the horizontal course set above the interior architrave of the temple. As such, they represent more than half of what now remains of the surviving sculptural decoration of the Parthenon.

Elgin's acquisitions also included objects from other buildings on the Athenian Acropolis: a Caryatid from Erechtheum; four slabs from the parapet frieze of the Temple of Athena Nike; and a number of other architectural fragments of the Parthenon, Propylaia, Erechtheum, the Temple of Athene Nike, and the Treasury of Atreus.

Legality of the removal from Athens[]

The Acropolis was at that time an Ottoman military fort, so Elgin required special permission to enter the site, the Parthenon, and the surrounding buildings. He stated that he had obtained a firman from the Sultan which allowed his artists to access the site, but he was unable to produce the original documentation. However, Elgin presented a document claimed to be an English translation of an Italian copy made at the time. This document is now kept in the British Museum.[34] Its authenticity has been questioned, as it lacked the formalities characterising edicts from the sultan. Vassilis Demetriades, Professor of Turkish Studies at the University of Crete, has argued that "any expert in Ottoman diplomatic language can easily ascertain that the original of the document which has survived was not a firman".[7] The document was recorded in an appendix of an 1816 parliamentary committee report. 'The committee permission' had convened to examine a request by Elgin asking the British government to purchase the Marbles. The report said that the document[35] in the appendix was an accurate translation, in English, of an Ottoman firman dated July 1801. In Elgin's view it amounted to an Ottoman authorisation to remove the marbles. The committee was told that the original document was given to Ottoman officials in Athens in 1801. Researchers have so far failed to locate it despite the fact that firmans, being official decrees by the Sultan, were meticulously recorded as a matter of procedure, and that the Ottoman archives in Istanbul still hold a number of similar documents dating from the same period.[6]

The parliamentary record shows that the Italian copy of the firman was not presented to the committee by Elgin himself but by one of his associates, the clergyman Rev. Philip Hunt. Hunt, who at the time resided in Bedford, was the last witness to appear before the committee and stated that he had in his possession an Italian translation of the Ottoman original. He went on to explain that he had not brought the document, because, upon leaving Bedford, he was not aware that he was to testify as a witness. The English document in the parliamentary report was filed by Hunt, but the committee was not presented with the Italian translation in Hunt's possession. William St. Clair, a contemporary biographer of Lord Elgin, said he possessed Hunt's Italian document and "vouches for the accuracy of the English translation". The committee report states on page 69 "(Signed with a signet.) Seged Abdullah Kaimacan" - however, the document presented to the committee was "an English translation of this purported translation into Italian of the original firman",[36] and had neither signet nor signature on it, a fact corroborated by St. Clair.[37] The 1967 study by British historian William St. Clair, Lord Elgin and the Marbles, stated the sultan did not allow the removal of statues and reliefs from the Parthenon. The study judged a clause authorising the British to take stones “with old inscriptions and figures” probably meant items in the excavations the site, not the art decorating the temples.[38]

The document allowed Elgin and his team to erect scaffolding so as to make drawings and mouldings in chalk or gypsum, as well as to measure the remains of the ruined buildings and excavate the foundations which may have become covered in the [ghiaja (meaning gravel, debris)]; and "...that when they wish to take away [qualche (meaning 'some' or 'a few')] pieces of stone with old inscriptions or figures thereon, that no opposition be made thereto". The interpretation of these lines has been questioned even by non-restitutionalists,[39][40] particularly the word qualche, which in modern language should be translated as a few but can also mean any. According to non-restitutionalists, further evidence that the removal of the sculptures by Elgin was approved by the Ottoman authorities is shown by a second firman which was required for the shipping of the marbles from Piraeus.[41]

Many have questioned the legality of Elgin's actions, including the legitimacy of the documentation purportedly authorising them. A study by Professor David Rudenstine of the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law concluded that the premise that Elgin obtained legal title to the marbles, which he then transferred to the British government, "is certainly not established and may well be false".[42] Rudenstine's argumentation is partly based on a translation discrepancy he noticed between the surviving Italian document and the English text submitted by Hunt to the parliamentary committee. The text from the committee report reads "We therefore have written this Letter to you, and expedited it by Mr. Philip Hunt, an English Gentleman, Secretary of the aforesaid Ambassador" but according to the St. Clair Italian document the actual wording is "We therefore have written this letter to you and expedited it by N.N.". In Rudenstine's view, this substitution of "Mr. Philip Hunt" with the initials "N.N." can hardly be a simple mistake. He further argues that the document was presented after the committee's insistence that some form of Ottoman written authorisation for the removal of the marbles be provided, a fact known to Hunt by the time he testified. Thus, according to Rudenstine, "Hunt put himself in a position in which he could simultaneously vouch for the authenticity of the document and explain why he alone had a copy of it fifteen years after he surrendered the original to Ottoman officials in Athens". On two earlier occasions, Elgin stated that the Ottomans gave him written permissions more than once, but that he had "retained none of them." Hunt testified on March 13, and one of the questions asked was "Did you ever see any of the written permissions which were granted [to Lord Elgin] for removing the Marbles from the Temple of Minerva?" to which Hunt answered "yes", adding that he possessed an Italian translation of the original firman. Nonetheless, he did not explain why he had retained the translation for 15 years, whereas Elgin, who had testified two weeks earlier, knew nothing about the existence of any such document.[37]

English travel writer Edward Daniel Clarke, an eyewitness, wrote that the Dizdar, the Ottoman fortress commander on the scene, attempted to stop the removal of the metopes but was bribed to allow it to continue.[43] In contrast, John Merryman, Sweitzer Professor of Law at Stanford Law School and also Professor of Art at Stanford University, putting aside the discrepancy presented by Rudenstine, argues that since the Ottomans had controlled Athens since 1460, their claims to the artefacts were legal and recognisable. Sultan Selim III was grateful to the British for repelling Napoleonic expansion, and unlike his Hellenophile ancestor Mehmet II, the Parthenon marbles had no sentimental value to him.[29] Further, that written permission exists in the form of the firman, which is the most formal kind of permission available from that government, and that Elgin had further permission to export the marbles, legalises his (and therefore the British Museum's) claim to the Marbles.[41] He does note, though, that the clause concerning the extent of Ottoman authorisation to remove the marbles "is at best ambiguous", adding that the document "provides slender authority for the massive removals from the Parthenon ... The reference to 'taking away any pieces of stone' seems incidental, intended to apply to objects found while excavating. That was certainly the interpretation privately placed on the firman by several of the Elgin party, including Lady Elgin. Publicly, however, a different attitude was taken, and the work of dismantling the sculptures on the Parthenon and packing them for shipment to England began in earnest. In the process, Elgin's party damaged the structure, leaving the Parthenon not only denuded of its sculptures but further ruined by the process of removal. It is certainly arguable that Elgin exceeded the authority granted in the firman in both respects".[44]

The issue of firmans of this nature, along with universally required bribes, was not unusual at this time: In 1801 for example, Edward Clarke and his assistant John Marten Cripps, obtained an authorisation from the governor of Athens for the removal of a statue of the goddess Demeter which was at Eleusis, with the intervention of Italian artist Giovanni Battista Lusieri who was Lord Elgin's assistant at the time.[45] Prior to Clarke, the statue had been discovered in 1676 by the traveller George Wheler, and since then several ambassadors had submitted unsuccessful applications for its removal,[46][47] but Clarke had been the one to remove the statue by force,[48] after bribing the waiwode of Athens and obtaining a firman,[46] despite the objections and a riot,[48][49] of the local population who unofficially, and against the traditions of the iconoclastic Church, worshiped the statue as the uncanonised Saint Demetra (Greek: Αγία Δήμητρα).[48] The people would adorn the statue with garlands,[48] and believed that the goddess was able to bring fertility to their fields and that the removal of the statue would cause that benefit to disappear.[46][48][50][51] Clarke also removed other marbles from Greece such as a statue of Pan, a figure of Eros, a comic mask, various reliefs and funerary steles, amongst others. Clarke donated these to the University of Cambridge and subsequently in 1803 the statue of Demeter was displayed at the university library. The collection was later moved to the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge where it formed one of the two main collections of the institution.[46]

Contemporary reaction[]

The contemporary museum director in the Louvre had no doubt around the legality of the acquisition of Lord Elgin. During the art restitutions of post-Napoleonic France to other European States, Vivant Denon, then director of former Musee Napoleon then Louvre, wrote in a private letter to the French ambassador Talleyrand who was then engaged in the Congress of Vienna: "If we yield to the claims (for art restitution) of Holland and Belgium, we deprive the Museum of one of its greatest assets, that of having a series of excellent colorists... Russia is not hostile, Austria has had everything returned, Prussia has a restoration more complete.... There remains only England, who has in truth nothing to claim, but who, since she has just bought the bas-reliefs of which Lord Elgin plundered the Temple at Athens, now thinks she can become a rival of the Museum [Louvre], and wants to deplete this Museum in order to collect the remains for her" (Denon to Talleyrand, quoted in Saunier, p. 114; Muintz, in Nouvelle Rev., CVII, 2OI). Vivant Denon uses clearly the verb "plunder" in French.

When the marbles were shipped to England, they were "an instant success among many"[9] who admired the sculptures and supported their arrival, but both the sculptures and Elgin also received criticism from detractors. Lord Elgin began negotiations for the sale of the collection to the British Museum in 1811, but negotiations failed despite the support of British artists[9] after the government showed little interest. Many Britons opposed purchase of the statues because they were in bad condition and therefore did not display the "ideal beauty" found in other sculpture collections.[9] The following years marked an increased interest in classical Greece, and in June 1816, after parliamentary hearings, the House of Commons offered £35,000 (equivalent to £2,700,000 in 2019 pounds) in exchange for the sculptures. Even at the time the acquisition inspired much debate, although it was supported by "many persuasive calls" for the purchase.[9]

Lord Byron strongly objected to the removal of the marbles from Greece, denouncing Elgin as a vandal.[10] His point of view about the removal of the Marbles from Athens is also mentioned in his narrative poem Childe Harold's Pilgrimage, published in 1812, which itself was largely inspired by Byron's travels around the Mediterranean and the Aegean Sea between 1809 and 1811:[52]

Dull is the eye that will not weep to see

Thy walls defaced, thy mouldering shrines removed

By British hands, which it had best behoved

To guard those relics ne'er to be restored.

Curst be the hour when from their isle they roved,

And once again thy hapless bosom gored,

And snatch'd thy shrinking gods to northern climes abhorred!

Byron was not the only one to protest against the removal at the time. Sir John Newport said:[53]

The Honourable Lord has taken advantage of the most unjustifiable means and has committed the most flagrant pillages. It was, it seems, fatal that a representative of our country loot those objects that the Turks and other barbarians had considered sacred.

Edward Daniel Clarke witnessed the removal of the metopes and called the action a "spoliation", writing that "thus the form of the temple has sustained a greater injury than it had already experienced from the Venetian artillery," and that "neither was there a workman employed in the undertaking ... who did not express his concern that such havoc should be deemed necessary, after moulds and casts had been already made of all the sculpture which it was designed to remove."[43] When Sir Francis Ronalds visited Athens and Giovanni Battista Lusieri in 1820, he wrote that "If Lord Elgin had possessed real taste in lieu of a covetous spirit he would have done just the reverse of what he has, he would have removed the rubbish and left the antiquities."[54][55]

A parliamentary committee investigating the situation concluded that the monuments were best given "asylum" under a "free government" such as the British one.[9] In 1810, Elgin published a defence of his actions,[4] but the subject remained controversial. A public debate in Parliament followed Elgin's publication, and Parliament again exonerated Elgin's actions, eventually deciding to purchase the marbles for the "British nation" in 1816 by a vote of 82–30.[10] Among the supporters of Elgin was the painter Benjamin Robert Haydon.[9] He was followed by Felicia Hemans in her Modern Greece: A Poem (1817), who there took direct issue with Byron, defying him with the question

And who may grieve that, rescued from their hands,

Spoilers of excellence and foes of art,

Thy relics, Athens! borne to other lands

Claim homage still to thee from every heart?

and quoting Haydon and other defenders of their accessibility in her notes.[56] John Keats visited the British Museum in 1817 and recording his feelings in the sonnet titled "On Seeing the Elgin Marbles". William Wordsworth also viewed the marbles and commented favourably on their aesthetics in a letter to Haydon.[57]

Following the exhibition of the marbles in the British Museum, they were later displayed in the specially constructed Elgin Saloon (1832) until the Duveen Gallery was completed in 1939. The crowds packing in to view them set attendance records for the museum.[9]

Damage[]

Morosini[]

Prior damage to the marbles was sustained during successive wars, and it was during such conflicts that the Parthenon and its artwork sustained, by far, the most extensive damage. In particular, an explosion ignited by Venetian gun and cannon-fire bombardment in 1687, whilst the Parthenon was used as a munitions store during the Ottoman rule, destroyed or damaged many pieces of Parthenon art, including some of that later taken by Lord Elgin.[58] It was this explosion that sent the marble roof, most of the cella walls, 14 columns from the north and south peristyles, and carved metopes and frieze blocks flying and crashing to the ground, destroying much of the artwork. Further damage to the Parthenon's artwork occurred when the Venetian general Francesco Morosini looted the site of its larger sculptures. The tackle he was using to remove the sculptures proved to be faulty and snapped, dropping an over-life-sized sculpture of and the horses of Athena's chariot from the west pediment on to the rock of the Acropolis 40 feet (12 m) below.[59]

War of Independence[]

The Erechtheion was used as a munitions store by the Ottomans during the Greek War of Independence[60] (1821–1833) which ended the 355-year Ottoman rule of Athens. The Acropolis was besieged twice during the war, first by the Greeks in 1821–22 and then by the Ottoman forces in 1826–27. During the first siege the besieged Ottoman forces attempted to melt the lead in the columns to cast bullets, even prompting the Greeks to offer their own bullets to the Ottomans in order to minimize damage.[61]

Elgin[]

Elgin consulted with Italian sculptor Antonio Canova in 1803 about how best to restore the marbles. Canova was considered by some to be the world's best sculptural restorer of the time; Elgin wrote that Canova declined to work on the marbles for fear of damaging them further.[9]

To facilitate transport by Elgin, the columns' capitals and many metopes and frieze slabs were either hacked off the main structure or sawn and sliced into smaller sections, causing irreparable damage to the Parthenon itself.[62][63] One shipload of marbles on board the British brig Mentor[64] was caught in a storm off Cape Matapan in southern Greece and sank near Kythera, but was salvaged at the Earl's personal expense;[65] it took two years to bring them to the surface.

British Museum[]

The artefacts held in London suffered from 19th-century pollution which persisted until the mid-20th century and have suffered irreparable damage by previous cleaning methods employed by British Museum staff.[67]

As early as 1838, scientist Michael Faraday was asked to provide a solution to the problem of the deteriorating surface of the marbles. The outcome is described in the following excerpt from the letter he sent to Henry Milman, a commissioner for the National Gallery.[68][69]

The marbles generally were very dirty ... from a deposit of dust and soot. ... I found the body of the marble beneath the surface white. ... The application of water, applied by a sponge or soft cloth, removed the coarsest dirt. ... The use of fine, gritty powder, with the water and rubbing, though it more quickly removed the upper dirt, left much embedded in the cellular surface of the marble. I then applied alkalies, both carbonated and caustic; these quickened the loosening of the surface dirt ... but they fell far short of restoring the marble surface to its proper hue and state of cleanliness. I finally used dilute nitric acid, and even this failed. ... The examination has made me despair of the possibility of presenting the marbles in the British Museum in that state of purity and whiteness which they originally possessed.

A further effort to clean the marbles ensued in 1858. Richard Westmacott, who was appointed superintendent of the "moving and cleaning the sculptures" in 1857, in a letter approved by the British Museum Standing Committee on 13 March 1858 concluded[70]

I think it my duty to say that some of the works are much damaged by ignorant or careless moulding – with oil and lard – and by restorations in wax and resin. These mistakes have caused discolouration. I shall endeavour to remedy this without, however, having recourse to any composition that can injure the surface of the marble.

Yet another effort to clean the marbles occurred in 1937–38. This time the incentive was provided by the construction of a new Gallery to house the collection. The Pentelic marble mined from Mount Pentelicus north of Athens, from which the sculptures are made, naturally acquires a tan colour similar to honey when exposed to air; this colouring is often known as the marble's "patina"[71] but Lord Duveen, who financed the whole undertaking, acting under the misconception that the marbles were originally white[72] probably arranged for the team of masons working in the project to remove discolouration from some of the sculptures. The tools used were seven scrapers, one chisel and a piece of carborundum stone. They are now deposited in the British Museum's Department of Preservation.[72][73] The cleaning process scraped away some of the detailed tone of many carvings.[74] According to Harold Plenderleith, the surface removed in some places may have been as much as one-tenth of an inch (2.5 mm).[72]

The British Museum has responded with the statement that "mistakes were made at that time."[75] On another occasion it was said that "the damage had been exaggerated for political reasons" and that "the Greeks were guilty of excessive cleaning of the marbles before they were brought to Britain."[73] During the international symposium on the cleaning of the marbles, organised by the British Museum in 1999, curator Ian Jenkins, deputy keeper of Greek and Roman antiquities, remarked that "The British Museum is not infallible, it is not the Pope. Its history has been a series of good intentions marred by the occasional cock-up, and the 1930s cleaning was such a cock-up". Nonetheless, he claimed that the prime cause for the damage inflicted upon the marbles was the 2000-year-long weathering on the Acropolis.[76]

American archeologist Dorothy King, in a newspaper article, wrote that techniques similar to the ones used in 1937–38 were applied by Greeks as well in more recent decades than the British, and maintained that Italians still find them acceptable.[29] The British Museum said that a similar cleaning of the Temple of Hephaestus in the Athenian Agora was carried out by the conservation team of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens[77] in 1953 using steel chisels and brass wire.[65] According to the Greek ministry of Culture, the cleaning was carefully limited to surface salt crusts.[76] The 1953 American report concluded that the techniques applied were aimed at removing the black deposit formed by rain-water and "brought out the high technical quality of the carving" revealing at the same time "a few surviving particles of colour".[77]

Documents released by the British Museum under the Freedom of Information Act revealed that a series of minor accidents, thefts and acts of vandalism by visitors have inflicted further damage to the sculptures.[78] This includes an incident in 1961 when two schoolboys knocked off a part of a centaur's leg. In June 1981, a west pediment figure was slightly chipped by a falling glass skylight, and in 1966 four shallow lines were scratched on the back of one of the figures by vandals. In 1970 letters were scratched on to the upper right thigh of another figure. Four years later, the dowel hole in a centaur's hoof was damaged by thieves trying to extract pieces of lead.[78]

Athens[]

Air pollution and acid rain have damaged the marble and stonework.[79] The last remaining slabs from the western section of the Parthenon frieze were removed from the monument in 1993 for fear of further damage.[80] They have now been transported to the New Acropolis Museum.[79]

Until cleaning of the remaining marbles was completed in 2005,[81] black crusts and coatings were present on the marble surface.[82] The laser technique applied on the 14 slabs that Elgin did not remove revealed a surprising array of original details, such as the original chisel marks and the veins on the horses' bellies. Similar features in the British Museum collection have been scraped and scrubbed with chisels to make the marbles look white.[83][84] Between January 20 and the end of March 2008, 4200 items (sculptures, inscriptions small terracotta objects), including some 80 artefacts dismantled from the monuments in recent years, were removed from the old museum on the Acropolis to the new Parthenon Museum.[85][86] Natural disasters have also affected the Parthenon. In 1981, an earthquake caused damage to the east façade.[87]

Since 1975, Greece has been restoring the Acropolis. This restoration has included replacing the thousands of rusting iron clamps and supports that had previously been used, with non-corrosive titanium rods;[88] removing surviving artwork from the building into storage and subsequently into a new museum built specifically for the display of the Parthenon art; and replacing the artwork with high-quality replicas. This process has come under fire from some groups as some buildings have been completely dismantled, including the dismantling of the Temple of Athena Nike and for the unsightly nature of the site due to the necessary cranes and scaffolding.[88] But the hope is to restore the site to some of its former glory, which may take another 20 years and 70 million euros, though the prospect of the Acropolis being "able to withstand the most extreme weather conditions – earthquakes" is "little consolation to the tourists visiting the Acropolis" according to The Guardian.[88] Under continuous international pressure, Directors of the British Museum have not ruled out agreeing to what they call a "temporary" loan to the new museum, but state that it would be under the condition of Greece acknowledging the British Museum's claims to ownership.[53]

Relocation debate[]

Rationale for returning to Athens[]

Those arguing for the Marbles' return claim legal, moral and artistic grounds. Their arguments include:

- The main stated aim of the Greek campaign is to reunite the Parthenon sculptures around the world in order to restore "organic elements" which "at present remain without cohesion, homogeneity and historicity of the monument to which they belong" and allow visitors to better appreciate them as a whole;[89][90][91]

- Presenting all the extant Parthenon Marbles in their original historical and cultural environment would permit their "fuller understanding and interpretation";[90][92]

- The marbles may have been obtained illegally and hence should be returned to their rightful owner;[93]

- Returning the Parthenon sculptures (Greece is requesting only the return of sculptures from this particular building) would not set a precedent for other restitution claims because of the distinctively "universal value" of the Parthenon;[94]

- Safekeeping of the marbles would be ensured at the New Acropolis Museum, situated to the south of the Acropolis hill. It was built to hold the Parthenon sculpture in natural sunlight that characterises the Athenian climate, arranged in the same way as they would have been on the Parthenon. The museum's facilities have been equipped with state-of-the-art technology for the protection and preservation of exhibits;[95]

- The friezes are part of a single work of art, thus it was unintended that fragments of this piece be scattered across different locations;

- Casts of the marbles would be just as able to demonstrate the cultural influences which Greek sculptures have had upon European art as would the original marbles, whereas the context with which the marbles belong cannot be replicated within the British Museum, however, the Greek plan is to still house them in a museum in Athens;

- A 2014 yougov poll suggested that more British people (37%) supported the marbles' restoration to Greece than opposed it (23%)[96]

- British conservation claims at the time when Parthenon Marbles were sent to the British Museum seem controversial, especially if compared to contemporary British expeditions carried out in other parts of the Greek world, that is Sicily. In 1823, British architects Samuel Angell and William Harris excavated at Selinus in the course of their tour of Sicily, where they discovered the sculptured metopes from the Archaic temple of “Temple C.” Although local Sicilian officials tried to stop them, they continued their work, and attempted to export their finds to England, destined for the British Museum. In the echos of the activities of Lord Elgin in Athens, Angell and Harris's shipments were only diverted to Palermo by force of the Bourbon authorities and are now kept in the Palermo archeological museum.[97]

In a 2018 interview to the Athens newspaper Ta Nea, British Labour party leader Jeremy Corbyn did not rule out returning the Marbles to Greece, stating, "As with anything stolen or taken from occupied or colonial possession—including artefacts looted from other countries in the past—we should be engaged in constructive talks with the Greek government about returning the sculptures."[98]

Rationale for remaining in London[]

A range of different arguments have been presented by scholars,[53] British political leaders and British Museum spokespersons over the years in defence of retention of the Parthenon Marbles by the British Museum. The main points include:

- The assertion that fulfilling all restitution claims would empty most of the world's great museums – this has also caused concerns among other European and American museums, with one potential target being the famous bust of Nefertiti in Berlin's Neues Museum; in addition, portions of Parthenon marbles are kept by many other European museums.[29]

- Advocates of the British Museum's position also point out that the Marbles in Britain receive about 6 million visitors per year as opposed to 1.5 million visitors to the Acropolis Museum. The removal of the Marbles to Greece would therefore, they argue, significantly reduce the number of people who have the opportunity to visit the Marbles.[99]

- Another argument for keeping the Parthenon Marbles within the UK has been made by J. H. Merryman, Sweitzer Professor of Law at Stanford University and co-operating professor in the Stanford Art Department. He has argued that "the Elgin Marbles have been in England since 1821 and in that time have become a part of the British cultural heritage."[100] However he has also argued that if the Parthenon were actually being restored, there would be a moral argument for returning the Marbles to the temple whence they came, and thus restoring its integrity.[citation needed] The English Romantic poet John Keats, and the French sculptor Auguste Rodin, are notable examples of visitors to the Parthenon Marbles after their removal to England who subsequently produced famous work inspired by them.[101][102]

- It would be impossible to reunite the marbles as a complete set on the Parthenon due to corrosion from Athenian smog and because about half of them were destroyed in an explosion in 1687.[29] The Greek plan is to transfer them to the Acropolis Museum instead.[95]

- The assertion that Modern Greeks have "no claim to the stones because you could see from their physiognomy that they were not descended from the men who had carved them," a quote attributed to Auberon Waugh.[103] In nineteenth century Western Europe, Greeks of the Classical period were widely imagined to have been light skinned and blond.[104]

- The assertion that Greece could mount no court case, because Elgin claims to have been granted permission by what was then Greece's ruling government and a legal principle of limitation would apply, i.e., the ability to pursue claims expires after a period of time prescribed by law.[53]

- It would be illegal under current law to return the marbles. This was tested in the English High Court in May 2005 in relation to Nazi-looted Old Master artworks held at the British Museum, which the Museum's Trustees wished to return to the family of the original owner; the Court found that due to the British Museum Act 1963 these works could not be returned without further legislation. The judge, Mr Justice Morritt, found that the Act, which protects the collections for posterity, could not be overridden by a "moral obligation" to return works, even if they are believed to have been plundered.[105][106] It has been argued, however, that the case was not directly relevant to the Parthenon Marbles, as it was about a transfer of ownership, and not the loan of artefacts for public exhibition overseas, which is provided for in the 1963 Act.[107][better source needed]

The Trustees of the British Museum make the following statement on the Museum website in response to arguments for the relocation of the Parthenon Marbles to the Acropolis Museum:

The Acropolis Museum allows the Parthenon sculptures that are in Athens to be appreciated against the backdrop of ancient Greek and Athenian history. This display does not alter the Trustees’ view that the sculptures are part of everyone's shared heritage and transcend cultural boundaries. The Trustees remain convinced that the current division allows different and complementary stories to be told about the surviving sculptures, highlighting their significance for world culture and affirming the universal legacy of ancient Greece.[108][109]

It was reported on 12 March 2021 that British Prime Minister Boris Johnson told a Greek newspaper Ta Nea that the British Museum was the legitimate owner of the marbles and that “They [the marbles] were acquired legally by Lord Elgin, in line with the laws that were in force at that time.”[110]

Public perception of the issue[]

Popular support for restitution[]

Outside Greece a campaign for the Return of the Marbles began in 1981 with the formation of the International Organising Committee - Australia - for the Restitution of the Parthenon Marbles, and in 1983 with the formation of the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles. International organisations such as UNESCO and the International Association for the Reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures, as well as campaign groups such as, Marbles Reunited, and stars of Hollywood, such as George Clooney and Matt Damon, as well as Human Rights activists, lawyers, and the people of the arts, voiced their strong support for the return of the Parthenon Marbles to Greece.

American actor George Clooney voiced his support for the return by the United Kingdom and reunification of the Parthenon Marbles in Greece, during his promotional campaign for his 2014 film The Monuments Men which retells the story of Allied efforts to save important masterpieces of art and other culturally important items before their destruction by Hitler and the Nazis during World War II. His remarks regarding the Marbles reignited the debate in the United Kingdom about their return to their home country. Public polls were also carried out by newspapers in response to Clooney's stance on this matter.

TV presenter and producer William G. Stewart was a high-profile supporter of the campaign and regularly referenced the Marbles on his quiz show Fifteen-to-One. On an episode in 2001 Stewart gave a presentation stating the case for their return, fulfilling a promise to do so if too few contestants survived the first round to continue the game.

An internet campaign site,[111] in part sponsored by Metaxa, aims to consolidate support for the return of the Parthenon Marbles to the New Acropolis Museum in Athens.

Noted public intellectual Christopher Hitchens had, at numerous times, argued for their repatriation.[112]

In BBC TV Series QI (series 12, episode 7, XL edition), host Stephen Fry provided his support for the return of the Parthenon Marbles while recounting the story of the Greeks giving lead shot to their Ottoman Empire enemies, as the Ottomans were running out of ammunition, in order to prevent damage to the Acropolis. Fry had previously written a blog post along much the same lines in December 2011 entitled "A Modest Proposal", signing off with "It's time we lost our marbles".[113]

Opinion polls[]

A YouGov poll in 2014 suggested that more British people (37%) supported the marbles' restoration to Greece than opposed it (23%).[97]

In older polls, Ipsos MORI asked in 1998, "If there were a referendum on whether or not the Elgin Marbles should be returned to Greece, how would you vote?" This returned these values from the British general adult population:[114]

- 40% in favour of returning the marbles to Greece

- 15% in favour of keeping them at the British Museum

- 18% would not vote

- 27% had no opinion

Another opinion poll in 2002 (again carried out by MORI) showed similar results, with 40% of the British public in favour of returning the marbles to Greece, 16% in favour of keeping them within Britain and the remainder either having no opinion or would not vote.[115] When asked how they would vote if a number of conditions were met (including, but not limited to, a long-term loan whereby the British maintained ownership and joint control over maintenance) the number responding in favour of return increased to 56% and those in favour of keeping them dropped to 7%.

Both MORI poll results have been characterised by proponents of the return of the Marbles to Greece as representing a groundswell of public opinion supporting return, since the proportion explicitly supporting return to Greece significantly exceeds the number who are explicitly in favour of keeping the Marbles at the British Museum.[114][116]

A psychological view[]

One commentator on the controversies raised by former objects of worship held in museums draws a parallel between public responses to such works as the Elgin Marbles, the Benin Bronzes and (outside London) the Sultanganj Buddha. From the sociological view, there is something about these special examples that seems to draw to themselves strong emotional responses either of devotion or of rejection, the latter sometimes taking the form of wishing to be rid of their presence by sending them back to where they came from. Though encountered now in a radically different environment, such artefacts "and the capacity of humans to recognize [their charisma] and be drawn to it, is clearly not a phenomenon limited to cultural and religious contexts in which such behaviour is officially endorsed". The controversy they elicit arises as a psychological response, an "iconoclash", transcending questions of right or wrong.[117]

Other displaced Parthenon art[]

The remainder of the surviving sculptures that are not in museums or storerooms in Athens are held in museums in various locations across Europe. The British Museum also holds additional fragments from the Parthenon sculptures acquired from various collections that have no connection with Lord Elgin.

The collection held in the British Museum includes the following material from the Acropolis:

- Parthenon: 247 ft (75 m) of the original 524 ft (160 m) frieze

- 15 of the 92 metopes

- 17 pedimental figures, including a figure of a river-god, possibly the river Ilisus;[119]

- various pieces of architecture

- Erechtheion: a Caryatid, a column and other architectural members

- Propylaia: Architectural members

- Temple of Athena Nike: 4 slabs of the frieze and architectural members

British Museum loan[]

The British Museum lent the figure of a river-god, possibly the river Ilisus, to the State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg to celebrate its 250th anniversary.[120] It was on display there from Saturday 6 December 2014 until Sunday 18 January 2015. This was the first time the British Museum had lent part of its Parthenon Marbles collection and it caused some controversy.[121]

See also[]

- Imperial Spoils: The Curious Case of the Elgin Marbles

- Greece–United Kingdom relations

- Persepolis Administrative Archives

- University of Chicago Persian antiquities crisis

- Koh-i-Noor

- Palermo Fragment

References[]

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ "What are the 'Elgin Marbles'?". britishmuseum.org. Archived from the original on 20 April 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- ^ "Elgin Marbles – Greek sculpture". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Encyclopædia Britannica, Elgin Marbles, 2008, O.Ed.

- ^ Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons. Select Committee on the Earl of Elgin's Collection of Sculptured Marbles. (1816). Report from the Select Committee of the House of Commons on the Earl of Elgin's collection of sculptured marbles. London: Printed for J. Murray, by W. Bulmer and Co.

- ^ Jump up to: a b David Rudenstein (29 May 2000). "Did Elgin Cheat at Marbles?". Nation. 270 (21): 30.

Yet no researcher has ever located this Ottoman document and when l was in Instanbul I searched in vain for it or any copy of it, or any reference to it in other sorts of documents or a description of its substantive terms in any related official papers. Although a document of some sort may have existed, it seems to have vanished into thin air, despite the fact the Ottoman archives contain an enormous number of similar documents from the period.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Professor Vassilis Demetriades. "Was the removal of the marbles illegal?". newmentor.net.

- ^ "The Frieze | Acropolis Museum". www.theacropolismuseum.gr. Archived from the original on 6 December 2020. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Casey, Christopher (30 October 2008). ""Grecian Grandeurs and the Rude Wasting of Old Time": Britain, the Elgin Marbles, and Post-Revolutionary Hellenism". Foundations. Volume III, Number 1. Archived from the original on 13 May 2009. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Encyclopædia Britannica, The Acropolis, p.6/20, 2008, O.Ed.

- ^ Linda Theodorou; Dana Facaros (2003). Greece (Cadogan Country Guides). Cadogan Guides. p. 55. ISBN 1-86011-898-4.

- ^ Dyson, Stephen L. (2004). Eugenie Sellers Strong: portrait of an archaeologist. London: Duckworth. ISBN 0-7156-3219-1.

- ^ Mark Ellingham, Tim Salmon, Marc Dubin, Natania Jansz, John Fisher, Greece: The Rough Guide, Rough Guides, 1992,ISBN 1-85828-020-6, p.39

- ^ Chester Charlton McCown, The Ladder of Progress in Palestine: A Story of Archaeological Adventure, Harper & Bros., 1943, p.2

- ^ Graham Huggan, Stephan Klasen, Perspectives on Endangerment, Georg Olms Verlag, 2005, ISBN 3-487-13022-X, p.159

- ^ "Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons. Select Committee on the Earl of Elgin's Collection of Sculptured Marbles, Printed for J. Murray, by W. Bulmer and Co., 1816". Google ebook. 1816.

- ^ "The Parthenon Sculptures: The position of the Trustees of the British Museum". British Museum.

- ^ "The Background of the Removal". Greek Ministry of Culture.

- ^ "Acropolis, Athens". UNESCO.

- ^ "Greece wants Parthenon Marbles back, Tsipras tells May". 26 June 2018. Retrieved 25 December 2018 – via www.reuters.com.

- ^ "UNESCO Letter to British Government for the return of Parthenon's Marbles". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 19 October 2014. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- ^ "UK has not written back to UNESCO Letter" (PDF). UNESCO.

- ^ "Elgin Marbles: UK declines mediation over Parthenon sculptures". BBC News. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- ^ Theodor E. Mommsen, The Venetians in Athens and the Destruction of the Parthenon in 1687, American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 45, No. 4 (October – December 1941), pp. 544–556

- ^ Fichner-Rathus, Lois (2012). Understanding Art (10 ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 305. ISBN 978-1-111-83695-5.

- ^ Chatziaslani, Kornilia. "Morosini in Athens". Archaeology of the City of Athens. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ Tomkinson, John L. "Venetian Athens: Venetian Interlude (1684–1689)". Anagnosis Books. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ Grafton, Anthony; Glenn W. Most; Salvatore Settis (2010). The Classical Tradition. Harvard University Press. p. 693. ISBN 978-0-674-03572-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f King, Dorothy (21 July 2004). "Elgin Marbles: fact or fiction?". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- ^ Busuttil, Cynthia (26 July 2009). "Dock 1 made from ancient ruins?". The Times. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica Online"Elgin Marbles". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ^ Mitgang, Herbert (19 August 1989). "Books of The Times; Refueling the Elgin Marbles Debate". Retrieved 25 December 2018 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ As reported by John E. Simmons in: Museums: A History, chapter 7, Rowman & Littlefield, 07.07.2016 - 326 pages

- ^ St Clair, William: Lord Elgin and the Marbles. Oxford University Press, US, 3 edition (1998)

- ^ "firman". newmentor.net.

- ^ Gibbon, Kate Fitz (2005). Who Owns the Past?: Cultural Policy, Cultural Property, and the Law. Rutgers University Press. p. 115.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rudenstine, David. "Did Elgin cheat the Marbles?". The Nation.

- ^ "How the Parthenon Lost Its Marbles". 28 March 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^ Merryman, John Henry (1985). "Thinking about the Elgin Marbles". Michigan Law Review. 83 (8): 1898–1899. doi:10.2307/1288954. JSTOR 1288954.

- ^ English translation of the firman "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 10 May 2015. Retrieved 2014-12-07.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Merryman, John Henry (2006). "Whither the Elgin Marbles?". Imperialism, Art And Restitution. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Rudenstine, David (1999). "The Legality of Elgin's Taking: A Review Essay of Four Books on the Parthenon Marbles". International Journal of Cultural Property. 8 (1): 356–376.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Edward Daniel Clarke (1818). Travels in various Countries of Europe, Asia and Africa Part the Second Greece Egypt and the Holy Land Section the Second Fourth Edition Volume the Sixth. London: T. Cadell. p. 223ff.

- ^ James A. R. Nafziger; Robert Kirkwood Paterson; Alison Dundes Renteln (2010). Cultural Law: International, Comparative, and Indigenous. Cambridge University Press. p. 397. ISBN 978-0-521-86550-0.

- ^ Brian Fagan (2006). From Stonehenge to Samarkand: An Anthology of Archaeological Travel Writing. Oxford University Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-19-516091-8.

Clarke and Cripps greatly admired the statue, which weighed over 2 tons (1.8 tonnes) and decided to take it to England. They were lucky to obtain a firman from the governor of Athens with the help of the gifted Italian artist Giovanni Lusieri, who was at the time working for Lord Elgin.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Wroth, Warwick William (1887). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 10. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 422.

His chief prize was obtained at Eleusis, whence he succeeded in carrying off the colossal Greek statue (of the fourth or third ...) supposed by Clarke to be ' Ceres ' (Demeter) herself, but now generally called a ' Kistophoros '... statue and with Clarke's other Greek marbles, was wrecked near Beachy Head, not far from the home of Mr. Cripps, whose ...

- ^ Nigel Spivey (2013). Greek Sculpture. Cambridge University Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-107-06704-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e John Cuthbert Lawson (2012). Modern Greek Folklore and Ancient Greek Religion: A Study in Survivals. Cambridge University Press. pp. 79–80. ISBN 978-1-107-67703-6.

Further, in open defiance of an iconoclastic Church, they retained an old statue of Demeter, and merely prefixing the title 'saint ' to the ... Then, in 1801, two Englishmen, named Clarke and Cripps, armed by the Turkish authorities with a license to plunder, perpetrated an act ... and in spite of a riot among the peasants of Eleusis removed by force the venerable marble; and that which was the visible form of ...

- ^ Patrick Leigh Fermor (1984). Mani: Travels in the Southern Peloponnese. Penguin Books. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-14-011511-6.

uncanonical 'St. Demetra', was Eleusis, the former home of her most sacred rites in the Eleusinian mysteries. ... for prosperous harvests until two Englishmen called Clark and Cripps, armed with a document from the local pasha, carried her off from the heart of the outraged and rioting peasantry, in 1801. ...

- ^ "Edward Daniel Clarke (1769–1822)". The Fitzwilliam Museum. Archived from the original on 2 March 2014.

- ^ Adolf Theodor F. Michaelis (1882). Ancient marbles in Great Britain, tr. by C.A.M. Fennell. p. 244.

Clarke who in company with J. M. Cripps (also of Jesus College, Cambridge), was lucky enough (AD 1801) to get possession of this colossus in spite of the objections of the people of Eleusis, and to ship it with great trouble.

- ^ "The story of the Elgin Marbles". International Herald Tribune. 14 July 2004. Archived from the original on 25 October 2011. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Romancing the Stones". Newsweek. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- ^ Ronalds, B.F. (2016). Sir Francis Ronalds: Father of the Electric Telegraph. London: Imperial College Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-78326-917-4.

- ^ "Sir Francis Ronalds' Travel Journal: Athens". Sir Francis Ronalds and his Family. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ Modern Greece, London 1817, p.45, 65-6

- ^ Andrew Bennett (2015). William Wordsworth in Context. Cambridge University Press. p. 304.

- ^ "Stanford Archaeopedia". Archived from the original on 14 March 2008.

- ^ "The Parthenon". cambridge.org.

- ^ "History". Archived from the original on 3 February 2009.

- ^ Hitchens Christopher, The Elgin Marbles: Should They Be Returned to Greece?, 1998, p.viii, ISBN 1-85984-220-8

- ^ "Greek Government's Memorandum" (PDF). Greek Ministry of Culture.

- ^ Where Gods Yearn for Long-Lost Treasures Archived 16 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times

- ^ "The Wreck of the Mentor on the Coast of the Island of Kythera and the Operation to Retrieve, Salvage, and Transport the Parthenon Sculptures to London (1802-1805)". Arts Books, Athens.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Parthenon Sculptures". British Museum.

- ^ Oddy, Andrew, Andrew Oddy The Conservation of Marble Sculptures in the British Museum before 1975 Archived 2 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine, 47(3).

- ^ Oddy, Andrew, "The Conservation of Marble Sculptures in the British Museum before 1975", in Studies in Conservation, vol. 47, no. 3, (2002), pp. 145–146, Quote: "However, for a short time in the late 1930s copper scrapers were used to remove areas of discolouration from the surface of the Elgin Marbles. New information is presented about this lamentable episode."

- ^ Oddy, Andrew, "The Conservation of Marble Sculptures in the British Museum before 1975", in Studies in Conservation, vol. 47, no. 3, (2002), p. 146

- ^ Jenkins, I., '"Sir, they are scrubbing the Elgin Marbles!" – some controversial cleanings of the Parthenon Sculptures', Minerva 10(6) (1999) 43–45.

- ^ Oddy, Andrew, "The Conservation of Marble Sculptures in the British Museum before 1975", in Studies in Conservation, vol. 47, no. 3, (2002), p. 148

- ^ Gardner, Ernest Arthur: A Handbook of Greek Sculpture. Published 1896 Macmillan; [1]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Oddy, Andrew, "The Conservation of Marble Sculptures in the British Museum before 1975", in Studies in Conservation, vol. 47, no. 3, (2002), p. 149

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Museum admits 'scandal' of Elgin Marbles". BBC News Online. 1 December 1999. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ^ Paterakis AB. [Untitled]. Studies in Conservation 46(1): 79-80, 2001 [2]

- ^ mistakes were made at that time Archived 5 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kennedy, Maev (1 December 1999). "Mutual attacks mar Elgin Marbles debate". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b J. M. Cook and John Boardman, "Archaeology in Greece, 1953", The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 74, (1954), p. 147

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hastings, Chris. Revealed: how rowdy schoolboys knocked a leg off one of the Elgin Marbles Archived 7 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Daily Telegraph, 15 May 2005. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Parthenon Marbles – Past And Future, Contemporary Review". Contemporary Review. 2001.

- ^ National Documentation Centre – Ministry of Culture Archived 5 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine, see History of the Frieze

- ^ "Springer Proceedings in Physics". United States Geological Survey. 7 November 2005. Retrieved 20 January 2009.[dead link]

- ^ "Preserving And Protecting Monuments". Springer Berlin Heidelberg. 14 August 2007. Archived from the original on 18 June 2009. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- ^ Meryle Secrest (1 November 2005). Duveen: A Life in Art. University of Chicago Press. p. 376. ISBN 978-0-226-74415-5.

They scraped and scrubbed and polished. They used steel wool, carborundum, hammers and copper chisels. ... But, in 1938, the kinds of tools used to clean the Elgin Marbles were routinely employed. ... The more pleased Duveen became as the workmen banged and scraped away, the more worried officials at the British Museum became.

- ^ "The Parthenon Marbles (or Elgin Marbles) Restoration to Athens, Greece – Elgin Marbles Dispute Takes New Twist". Parthenonuk.com. 3 December 2004. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 20 January 2009.

- ^ "Outdoor transfer of artefacts from the old to the new acropolis museum". Retrieved 29 December 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "News". New Acropolis Museum. Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- ^ "The Parthenon at Athens". www.goddess-athena.org. Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Smith, Helena. Repair of Acropolis started in 1975 - now it needs 20 more years and £47m Archived 17 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 10 June 2005. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ^ "Hellenic Ministry of Culture, Special Issues". Archived from the original on 17 October 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Nicoletta Divari-Valakou, (Director of the Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities of Athens), "Revisiting the Parthenon: National Heritage in the Age of Globalism" in Mille Gabriel & Jens Dahl, (eds.) Utimut : past heritage – future partnerships, discussions on repatriation in the 21st Century, Copenhagen : International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs and Greenland National Museum & Archives, (2008)

- ^ "European Parliament Resolution for the return of the Elgin Marbles". Greek Ministry of Culture. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ "Debate of the Elgin Marbles" (PDF). University of Sydney.

- ^ "Parthenon Fragments Won't Go Back Home". Elginism. 1 April 2007. Archived from the original on 15 June 2009. Retrieved 20 January 2009.

- ^ Nicoletta Divari-Valakou, (Director of the Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities of Athens), "Revisiting the Parthenon: National Heritage in the Age of Globalism" in Mille Gabriel & Jens Dahl, (eds.) Utimut : past heritage – future partnerships, discussions on repatriation in the 21st Century, Copenhagen : International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs and Greenland National Museum & Archives, (2008) passim; (see also Conference summary[permanent dead link])

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Bernard Tschumi Architects". arcspace.com. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- ^ "British people tend to want Elgin marbles returned". Yougov.co.uk. 18 October 2014. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Temple Decoration and Cultural Identity in the Archaic Greek World: The Metopes of Selinus". New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007. 370 pp. 30 June 2010. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- ^ "Corbyn vows to return Elgin Marbles to Greece if he becomes prime minister". The Independent.

- ^ Trend, Nick. "Why returning the Elgin Marbles would be madness". The Telegraph. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- ^ "Merryman paper" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 April 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ "Opinion: The Elgin Marbles should remain in the UK – and the British Museum's new exhibition proves it". The Independent. 7 May 2018. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- ^ Foundation, Poetry (25 December 2018). "On Seeing the Elgin Marbles by John Keats". Poetry Foundation. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- ^ "Daniel Hannan: On the Elgin Marbles, as on everything else, Corbyn's assumption is that Britain Is Always In The Wrong". Conservative Home.

- ^ Dream Nation: Enlightenment, Colonization, and the Institution of Modern Greece, Stathis Gourgouris p.142-143

- ^ Ruling tightens grip on Parthenon marbles Archived 3 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 27 May 2005. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- ^ Her Majesty's Attorney General v The Trustees of the British Museum, [2005] EWHC (Ch) 1089

- ^ "Article on the relevance of the Feldmann paintings judgment to the Elgin Marbles". Archived from the original on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ "The Parthenon Sculptures". British Museum. Archived from the original on 5 May 2012.

- ^ "The Parthenon Sculptures: The Trustees position". British Museum. Archived from the original on 22 November 2019.

- ^ Reuters Staff (12 March 2021). "Britain is legitimate owner of Parthenon marbles, UK's Johnson tells Greece". Reuters. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ "Bring Them Back". Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ "The Lovely Stones". Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ "A Modest Proposal". Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Public and MPs would return the Elgin Marbles!". ipsos-mori.com. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013.

- ^ "Return Of The Parthenon Marbles". Ipsos MORI. Archived from the original on 9 April 2014. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ "Opinion poll: Majority of Britons favor return of Parthenon Marbles". stosacucine.pk. Archived from the original on 15 June 2009. Retrieved 2009-01-20.

- ^ Christopher Wingfield, "Touching the Buddha: encounters with a charismatic object", chapter 4 in Museum Materialities, ed. Sandra Dudley, Routledge 2010

- ^ "Sculpture from the Parthenon's East Pediment". Smarthistory at Khan Academy. Archived from the original on 4 March 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ "Figure of a river-god from the west pediment of the Parthenon". britishmuseum.org. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- ^ "Loan to the State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg". britishmuseum.org. Archived from the original on 31 December 2014. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- ^ "Greek Statue Travels Again, but Not to Greece". www.nytimes.com. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

Bibliography[]

"A Downing Street spokeswoman" (2020), reportage of employee of Sky, Comcast NBCUniversal (2020) — Row over Elgin Marbles as EU demands return of 'unlawfully removed cultural objects', published by Sky News 19 February 2020 - accessed 2020-02-19

Further reading[]

- Beard, Mary (2010). The Parthenon (2nd ed.). Profile Books. ISBN 978-1-84668-349-7.

- Fehlmann, Marc (June 2007). "Casts and Connoisseurs: the early reception of the Elgin Marbles". Apollo: 44–51. Archived from the original on 6 May 2012.

- Greenfield, Jeanette (2007). The Return of Cultural Treasures (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80216-1.

- Hitchens, Christopher (1987). Imperial Spoils: The Curious Case of the Elgin Marbles. London: Chatto and Windus. ISBN 978-0-8090-4189-3. (with essays by Robert Browning and Graham Binns)

- Jenkins, Ian (1994). The Parthenon Frieze. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-2200-7.

- Jenkins, Tiffany (2016). Keeping Their Marbles: how the treasures of the past ended up in museums – and why they should stay there. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-965759-9.

- King, Dorothy (2006). The Elgin Marbles. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 978-0-09-180013-0.

- Queyrel, François (2008). Le Parthénon, Un monument dans l'Histoire. Paris: Bartillat. ISBN 978-2-84100-435-5. Archived from the original on 29 September 2008.

- St Clair, William (1998). Lord Elgin and the Marbles (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-288053-5.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Elgin Marbles. |

| Library resources about Elgin Marbles |

- Parthenon at Curlie

- Acropolis Museum

- The Parthenon Frieze

- The British Museum Parthenon pages

- An interpretation of the meaning of the Marbles

- Location of the parts of the Parthenon around the world

- Greek pupils demand return of Elgin Marbles BBC

Pros and cons of restitution[]

- The Restitution of the Parthenon Marbles

- Acropolis of Athens – One monument, one heritage

- British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles' site

- Marbles Reunited: Friends of the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles

- The International Association for the Reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures

- The International Organising Committee, Australia – For The Restitution Of The Parthenon Marbles

- Elginism – Collection of news articles relating to the Elgin Marbles

- A guide to the case for the restitution of the Parthenon Marbles

- Eight Reasons: Why the Parthenon Sculptures must be returned to Greece

- Gillen Wood, "The strange case of Lord Elgin's nose": the cultural context of the early 19th century debate over the marbles, the politics & the aesthetics, imperialism and hellenism

- Information about arguments for the marbles to be returned to Greece

- Marbles with an Attitude – a different approach to the cause of reuniting the Parthenon Marbles

- An argument for keeping the marbles at the British Museum

- Two memorandums submitted to the UK Parliamentary Select Committee on Culture, Media and Sport in 2000.

- Virtual Representation of The Parthenon Frieze

- Acropolis of Athens

- Art and cultural repatriation

- Greece–United Kingdom relations

- Greek and Roman sculptures in the British Museum

- History of museums

- History of Athens

- Marble sculptures in the United Kingdom

- Sculptures by Phidias

- Archaeological discoveries in Greece

- 19th century in Athens

- Horses in art