En passant

En passant (French: [ɑ̃ paˈsɑ̃], lit. in passing) is a move in chess.[1] It is a special pawn capture that can only occur immediately after a pawn makes a move of two squares from its starting square, and it could have been captured by an enemy pawn had it advanced only one square. The opponent captures the just-moved pawn "in passing" through the first square. The result is the same as if the pawn had advanced only one square and the enemy pawn had captured it normally.

The en passant capture must be made on the very next turn or the right to do so is lost.[3] En passant capture is a common theme in chess compositions.

The en passant capture rule was added in the 15th century when the rule that gave pawns an initial double-step move was introduced. It prevents a pawn from using the two-square advance to pass an adjacent enemy pawn without the risk of being captured.

| This article uses algebraic notation to describe chess moves. |

Conditions[]

A pawn on its fifth rank may capture an enemy pawn on an adjacent file that has moved two squares in a single move, as if the pawn had moved only one square. The conditions are:

- the capturing pawn must be on its fifth rank;

- the captured pawn must be on an adjacent file and must have just moved two squares in a single move (i.e. a double-step move);

- the capture can only be made on the move immediately after the enemy pawn makes the double-step move; otherwise, the right to capture it en passant is lost.

|

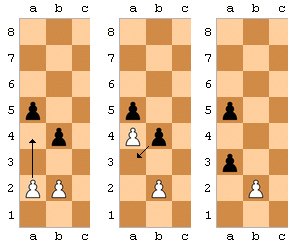

Black to move

The black pawn is on its initial square. If it moves to f6 (marked by ×), the white pawn can capture it.

|

White to move

Black moved their pawn forward two squares in a single move from f7 to f5, "passing" f6.

|

Black to move

White captures the pawn en passant, as if it had moved only one square to f6.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

En passant is a unique privilege of pawns—other pieces cannot capture en passant. It is the only capture in chess in which the capturing piece does not replace the captured piece on its square.[4]: 463

Notation[]

In either algebraic or descriptive chess notation, en passant captures are sometimes denoted by "e.p." or similar, but such notation is not required. In algebraic notation, the capturing move is written as if the captured pawn advanced only one square; for example, ...bxa3 or ...bxa3 e.p. (see beginning illustration).[5]: 216

Examples[]

In the opening[]

There are some examples of en passant in chess openings. In this line from Petrov's Defence, White can capture the pawn on d5 en passant on his sixth move.

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

- 1. e4 e5

- 2. Nf3 Nf6

- 3. d4 exd4

- 4. e5 Ne4

- 5. Qxd4 d5 (see diagram)

- 6. exd6 e.p.[6]: 124–125

Another example occurs in the French Defence after 1.e4 e6 2.e5, a move once advocated by Wilhelm Steinitz.[7]: 2 If Black responds with 2...d5, White can capture the pawn en passant with 3.exd6 e.p. Likewise, White can answer 2...f5 with 3.exf6 e.p.

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

An example is from this game by Steinitz and Bernhard Fleissig.[8]

- 1. e4 e6

- 2. e5 d5

- 3. exd6 e.p.

Unusual examples[]

capturing en passant

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

In the diagram, if Black plays 1...g5+, it seems to checkmate White, but it is in fact a blunder. Black overlooks that White can counter this check with the en passant capture 2.fxg6 e.p.#, which cross-checks and checkmates Black. This game is a draw if neither side makes an error.

Position after 12...f7–f5

|

After 14...g7–g5. White mates by taking the pawn en passant.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Another example is this game between Gunnar Gundersen and Albert H. Faul.[9] Black has just moved his pawn from f7 to f5. White could capture the f-pawn en passant with his e-pawn, but instead played:

- 13. h5+ Kh6 14. Nxe6+

The bishop on c1 effects a discovered check. 14...Kh7 results in 15.Qxg7#.

- 14... g5 15. hxg6 e.p.#

The en passant capture and discovered checks place Black in checkmate (from White's rook on h1, even without help from White's bishop). An en passant capture is the only way a double check can be delivered without one of the checking pieces moving, as in this case.

The largest known number of en passant captures in one game is three, shared by three games; in none of them were all three captures by the same player. The earliest known example is a 1980 game between Alexandru Sorin Segal and Karl Heinz Podzielny.[10]: 98–99 [11]

In chess compositions[]

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

En passant captures have often been used as a theme in chess compositions, as they "produce striking effects in the opening and closing of lines".[12]: 106 In the 1938 composition by Kenneth S. Howard, the key move 1. d4 introduces the threat of 2.d5+ cxd5 3.Bxd5#. Black can capture the d4-pawn en passant in either of two ways:

- The capture 1... exd3 e.p. shifts the e4-pawn from the e- to the d-file, preventing an en passant capture after White plays 2. f4. To stop the threatened mate (3.f5#), Black can advance 2... f5, but this allows White to play 3. exf6 e.p. with checkmate due to the decisive opening of the e-file.

- If Black plays 1... cxd3 e.p., White exploits the newly opened a2–g8 diagonal with 2. Qa2+ d5 3. cxd6 e.p.#

An example showing the effect en passant captures have on pins is this 1902 composition by Sommerfeldt:[13]

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

The key move

- 1. d4!

threatens 2.Qf2#. The moves of the black e-pawn are restricted in an unusual manner. The en passant capture 1...exd3 e.p.+ is illegal (it exposes the king to check), but

- 1... e3+

is legal. This, however, removes the black king's access to e3, allowing

- 2. d5#

Historical context[]

Allowing the en passant capture, together with the introduction of the two-square first move for pawns, was one of the last major rule changes in European chess, and occurred between 1200 and 1600.[a] In most places the en passant rule was adopted at the same time as allowing the pawn to move two squares on its first move, but it was not universally accepted until the Italian rules were changed in 1880.[6]: 124–125

The motivation for en passant was to prevent the newly added two-square first move for pawns from allowing a pawn to evade capture by an enemy pawn.[14]: 16

In chess variants[]

In most chess variants, if pawns are allowed to take two steps forward on their first move, the en passant rule is the same as in standard chess. Some larger variants allow pawns to make an initial move of more than two squares (such as the 16×16 game Chess on a Really Big Board, in which pawns may make up to six steps forward) − in such games en passant captures are usually allowed on any square the given pawn had just passed.

In variants with more than two spatial dimensions, en passant rules vary. In some three-dimensional chess variants, such as Millennium or Alice chess, en passant is allowed as long as the pawn's two-step move was not a purely vertical move. In 5D Chess with Multiverse Time Travel, en passant (and castling) are allowed in the normal spacial dimensions, but are not allowed across multiverses or across time.

Since the en passant rule relies on pawns advancing by more than one square, any chess variants that do not allow the initial two-step option for pawns (such as Dragonchess or Raumschach) also do not feature en passant captures in their set of rules. This includes all Asian variants, which only allow pawns to move one step at a time and thus cannot be captured en passant (in fact, pawns in shogi, xiangqi and janggi cannot even capture diagonally at all).

Threefold repetition and stalemate[]

The possibility of an en passant capture is relevant to the claim of a draw by threefold repetition and to the declaration of a draw by fivefold repetition. Two positions with the same configuration of pieces, with the same player to move, are for this purpose considered different if there was an opportunity to make an en passant capture in the first position, and that opportunity no longer exists in the second position.[15]: 27

In his book on chess organization and rules, International Arbiter Kenneth Harkness wrote that it is frequently asked if an en passant capture must be made if it is the only legal move.[16]: 49 This point was debated in the 19th century, with some arguing that the right to make an en passant capture is a "privilege" that one cannot be compelled to exercise. In his 1860 book Chess Praxis, Howard Staunton wrote that the en passant capture is mandatory in that instance. The rules of chess were amended to make this clear.[10] Today, it is settled that the player must make that move (or resign). The same is true if an en passant capture is the only move to get out of check.[16]: 49

See also[]

- Pawn

- Rules of chess

- "En passant (Chess)" by Edward Winter

Notes[]

- ^ Other relatively recent rule changes were castling, the unlimited range for queens and bishops[14]: 14, 16, 57 (Spanish master Ruy López de Segura gives the rule in his 1561 book Libro de la invencion liberal y arte del juego del axedrez[5]: 108 ) and a change to the rules on pawn promotion.

References[]

- ^ Brace, Edward (1977), "en passant", An Illustrated Dictionary of Chess, Secaucus, N.J: Craftwell, ISBN 1-55521-394-4

- ^ "FIDE Laws of Chess taking effect from 1 January 2018". FIDE. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ^ Article 3.7.4.2 in FIDE Laws of Chess[2]

- ^ Burgess, Graham (2000), The Mammoth Book of Chess (2nd ed.), New York: Carroll & Graf, ISBN 978-0-7867-0725-6

- ^ a b Golombek, Harry (1977), "en passant, capture", Golombek's Encyclopedia of Chess, Crown Publishing, ISBN 0-517-53146-1

- ^ a b Hooper, David; Whyld, Kenneth (1992), "en passant", The Oxford Companion to Chess (2nd ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-866164-9

- ^ Minev, Nikolay (1998), The French Defense 2: New and Forgotten Ideas, Davenport, Iowa: Thinkers' Press, ISBN 0-938650-92-0

- ^ "Steinitz vs. Fleissig, 1882". Chessgames.com.

- ^ "Gundersen vs. Faul". Chessgames.com. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- ^ a b Winter, Edward (1999), Stalemate, Chesshistory.com, retrieved 2009-06-12

- ^ A. Segal vs. K. Podzielny, Dortmund 1980. Published by 365Chess.com. Retrieved on 2009-12-05.

- ^ Howard, Kenneth S. (1961), How to Solve Chess Problems (2nd ed.), Dover, ISBN 978-0-486-20748-3, retrieved 2009-11-30

- ^ Open chess diary by Tim Krabbé - #234

- ^ a b Davidson, Henry (1949), A Short History of Chess (1981 paperback ed.), McKay, ISBN 0-679-14550-8

- ^ Schiller, Eric (2003), Official Rules of Chess (2nd ed.), Cardoza, ISBN 978-1-58042-092-1

- ^ a b Harkness, Kenneth (1967), Official Chess Handbook, McKay, ISBN 1-114-15703-1

Bibliography

| Look up en passant in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Just, Tim; Burg, Daniel B. (2003), U.S. Chess Federation's Official Rules of Chess (5th ed.), McKay, ISBN 0-8129-3559-4

- Winter, Edward (2006), Chess Facts and Fables, McFarland, ISBN 0-7864-2310-2

- Chess rules

- Chess terminology

- 15th century in chess